From June 2023

On shelves where local wines are sold, you can sometimes spot a Hill Country cabernet with the name Iconoclast on a label bearing the likeness of 19th-century Texas journalist William Brann. The vintage is an homage to Brann and the fiercely independent weekly he put out under that title in the 1890s in, of all places, Waco.

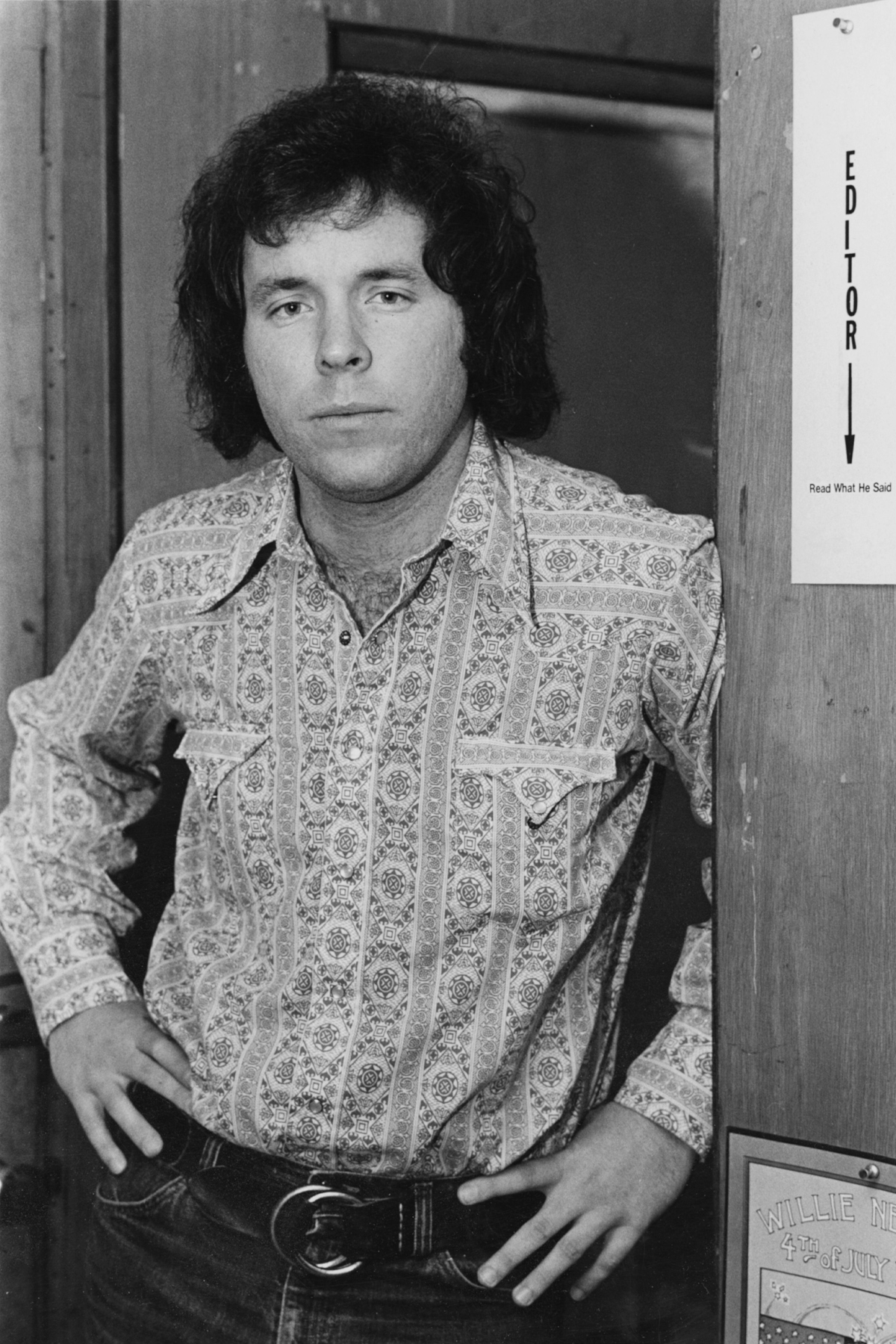

In the 1970s, Brann’s moniker was revived in Dallas as the banner of its “underground” newspaper, a publication that could be viewed now as an ancestor of the current Dallas Observer. I was its editor in 1974, during an unplanned professional detour that brought me back to my hometown, where I had been unable to get hired at the Dallas Morning News or Dallas Times Herald. I was living then in Washington, D.C., and freelancing for the Washington Star-News, but during a Christmas visit to Dallas to see my parents, I decided to go by the Iconoclast offices to pick up a small check they owed me for reprinting an interview I had done with Kris Kristofferson. I also wanted to meet the editor, a man named Jay Milner, a semifamous West Texan with a résumé that included the New York Herald Tribune.

The presence of Milner, who had taught journalism at SMU, was an indication the alternative weekly was outgrowing the hippie-hugging subculture of hookahs, waterbeds, and stoner FM radio born during the social upheavals of the 1960s and early ’70s. Every city had its underground paper, usually a tabloid with florid, psychedelic lettering on the masthead beckoning to the citizens of Woodstock nation, with articles about sex, drugs, and rock and roll, plus a helping of stick-it-to-the-man politics. During his tenure at the Iconoclast, Milner had deemphasized politics in favor of chronicling the new “outlaw” movement in country music headed by Willie Nelson. Willie who? I thought at the time. I’d grown up in a Unitarian house full of the liberal anthems of Pete Seeger and Judy Collins, plus the peace-loving Beatles and rock and roll. Country, by contrast, belonged to the politically backward my-country-right-or-wrong, Marine-haircut hordes that once flocked to the Big D Jamboree. Merle Haggard’s flag-waving “Okie From Muskogee” kind of said it all. How Willie Nelson fit into that world or why his bearded face was on the cover of an underground paper was beyond me.

The answers were contained in a song, “Up Against the Wall, Redneck Mother,” written by Oak Cliff’s Ray Wylie Hubbard and recorded by Jerry Jeff Walker on his contemporaneous “progressive country” breakthrough LP Viva Terlingua. Its lyrics about “kickin’ hippies’ asses and raisin’ hell” were a satirical riposte to “Okie From Muskogee,” yet acknowledged the line in the sand separating Hubbard and Walker and the readers of the Iconoclast from fellow citizens who saw long hair and beards as a threat to their way of life—an outrage that might require a stomping. When Willie, a Texan and author of honky-tonk hits for Patsy Cline and Ray Price, let his hair grow to his shoulders, left his coat and tie in Nashville, and relocated to Austin, it was clear which side of the line he was on. Cultures were colliding deep in the heart of Texas, and Milner and the Iconoclast were on it.

When I got to the tiny office at McKinney Avenue and Routh Street, Milner wasn’t there. No one was there but Doug Baker, the wide-eyed, young publisher. He welcomed me into the clutter of the main room, layout boards crammed end to end with strips of ragged-right, camera-ready copy. Baker was a few years older than I was and projected a rumpled essence, his wrinkled dress shirt bunched at his middle and stuffed unevenly into trousers that might have belonged to a suit. Dark hair, uncombed but not particularly long for 1974. You wouldn’t place him as the student radical who seven years earlier had started a rough and rowdy newspaper at SMU that was banned by university authorities. After Baker and a classmate took the paper off campus, it evolved into Dallas Notes, Dallas News, and then the Iconoclast.

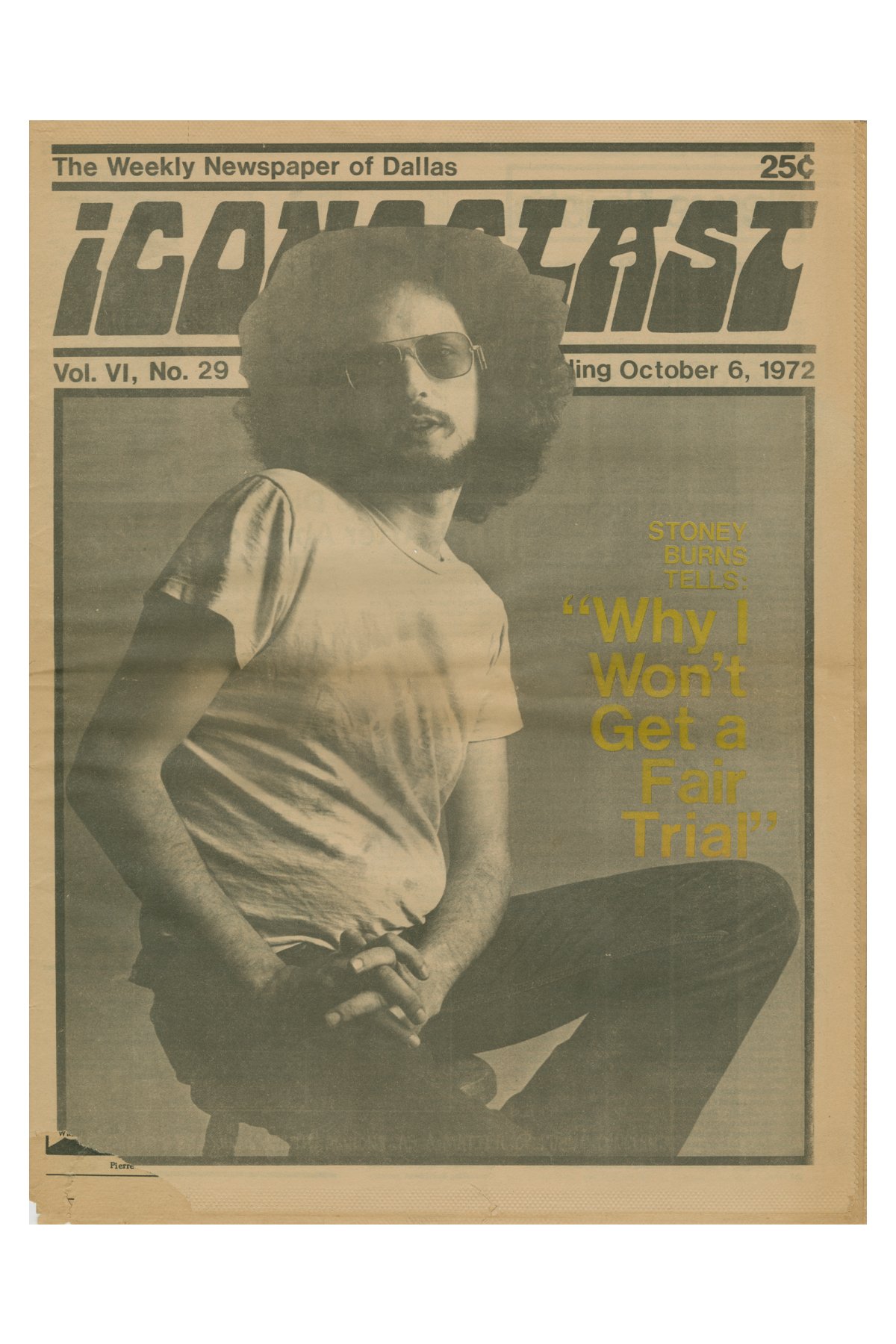

In the paper’s heyday, during the late ’60s, its offices were raided more than once by the Dallas police in search of contraband and things deemed obscene, such as sexually explicit comics. One of its early editors, Stoney Burns (real name: Brent Stein), became a local counterculture hero, taunting the authorities with his White-guy Afro, anti-establishment views, and whimsical defiance. The paper ran a full-frontal photo of a naked man dancing in a downtown parade, and the issue sold nearly 10,000 copies before being confiscated. It published a wire service story, ignored by the Dallas dailies, of the arrest of local Democratic Rep. Joe Poole in D.C. for drunken driving. In return for such journalistic enterprise, District Attorney Henry Wade’s office derided the paper’s editors as “the scum of the earth” and brought obscenity charges against Burns in a case that would reach the U.S. Supreme Court, where it was judged baseless. But the cops had the final say, arresting Burns for possession of one-eighth of an ounce of marijuana, enough at the time to get him 10 years in the state penitentiary at Huntsville. Mercifully, his sentence was commuted by Gov. Dolph Briscoe, a conservative Democrat. In time, Burns left the Iconoclast to start the music magazine Buddy and later told me, “The revolution is over. We lost.”

Baker apologized profusely for the oversight of my not being paid for the Kristofferson article, and then wrote out a check for $35 or whatever the amount was.

“How long are you going to be in town?” he asked.

He had just let Milner go over what might be termed “irreconcilable differences,” and most of the staff had followed. He had a problem. “Any chance you could come back tomorrow to help us get the paper out?”

He said he could pay me $100.

This is how I became the editor of the Iconoclast, the “Weekly Newspaper of Dallas.” I was planning to return to D.C., clutching the faint hope of a job at the failing Star-News. But then this happened. I had reservations about the Iconoclast and wasn’t sure I fit into its Zig Zag culture, but the job, I realized, would allow me to give Dallas another chance, plus put me in a position to offer my father, Gene, a gifted writer without portfolio, an opportunity to contribute columns and reviews (under a pseudonym to protect his employment at the Dallas Museum of Art).

I would be taking a professional risk by signing on with such a dodgy publication, but I was running out of options, and there seemed to be no middle ground. America was choosing up sides, and, come to think of it, I had been refused service once at Goff’s Hamburgers on Lovers Lane, when that proud American, Harvey Gough, noted my short beard and said, “We don’t serve hippies.” I eventually said yes to Baker and negotiated a salary of $150 a week, comparable to entry-level wages at the dailies. I wasn’t sure what I was in for, but I was in.

When I showed up the next week to begin officially as editor, after helping craft the press release announcing my appointment, I found the office only slightly less ghostly than the night I went by to pick up my check. One key staffer would not be returning, I was told, because he had “gone on the road with Billy Joe Shaver,” whatever that meant. An ad salesman had quit, something barely worthy of mention on any given day. On the premises were a receptionist, Pat, who was Doug’s wife, and Danny, the production manager and art director. Neither was very cheery nor said much, but their weary expressions carried the message: so you’re the next guy? Milner had been there less than a year; I wasn’t sure who preceded him.

Pat and Doug lived in a room behind the main office, amid the back issues and printing paraphernalia. Pat was not thrilled by this cost-saving stratagem, while Doug told me proudly that he lived on $40 a week and didn’t see why everyone else couldn’t do the same, evidence that he was walking the walk of anti-consumerism. He offered me his old one-bedroom apartment on McFarlin Boulevard, near SMU, as part of the editor’s package, and I took it. The rent was $100 a month.

Danny, who oversaw all the artwork and layout, was also in his 20s and, like everyone else at the Iconoclast, a refugee from the status quo and dedicated to overturning it. But his overriding concern, I soon learned, was the Kennedy assassination—and the many theories contradicting the official truth that Lee Harvey Oswald had been the lone gunman. The Kennedy assassination was a unifying topic at the paper and served as a distraction from the daily grind of putting out a muckraking tabloid every week in an unfriendly environment, i.e., Dallas.

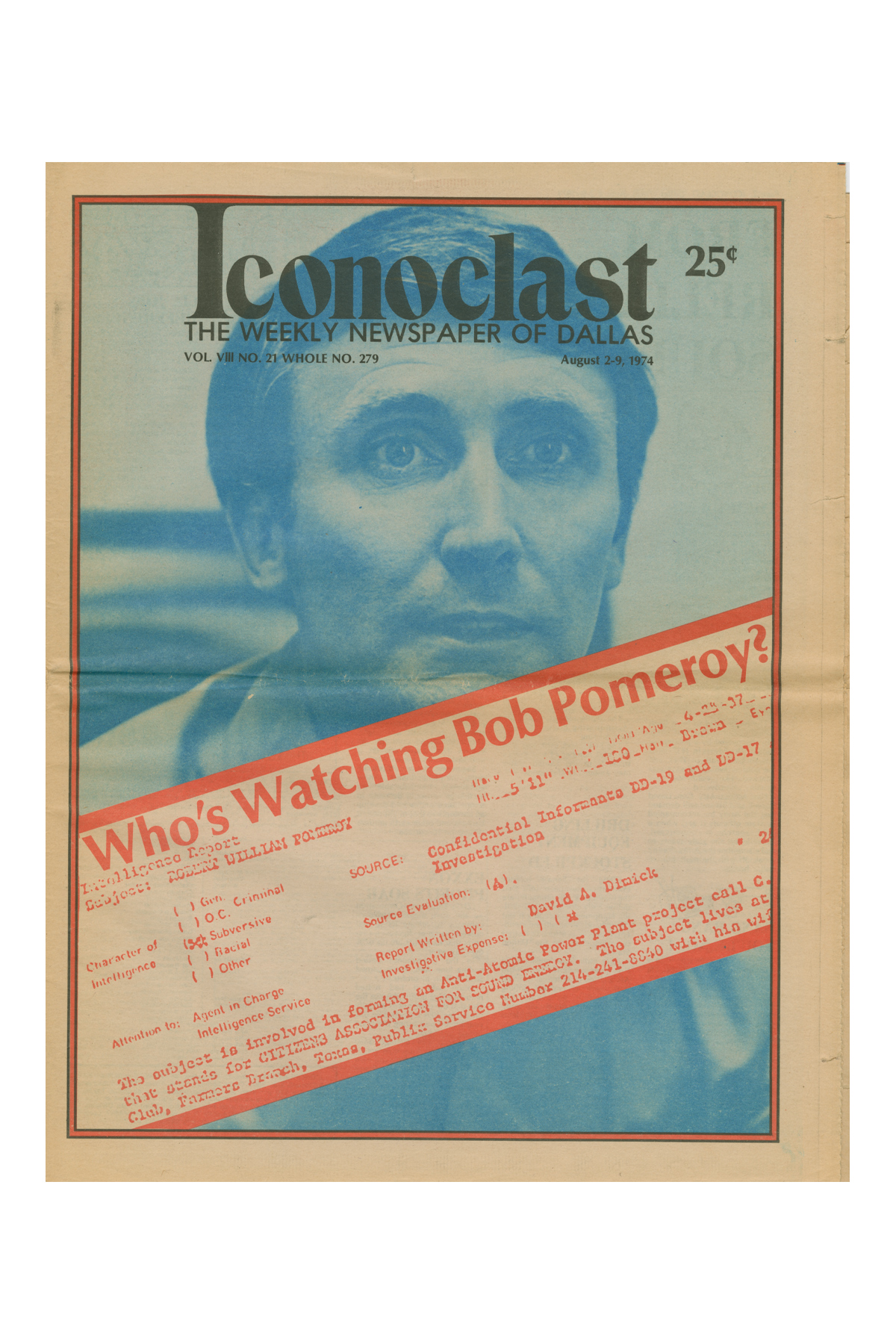

Like Doug, Danny exuded paranoia and spoke in a clenched whisper that seemed a sign of fatigue but also reflected an effort not to be overheard, especially if he was discussing the assassination. After one production night that ended, as always, close to dawn, we were seated at the counter of a diner, talking about you know what, when he turned, looked me in the eye, and said softly, “Keep your voice down,” nodding in the direction of a stranger sitting by himself a few stools away. The Iconoclast had run multiple stories debunking the Warren Commission Report (as Congress would do a few years later), and Danny believed that undercover agents were watching us and possibly had even infiltrated the paper. At one point, he confided to me that he wondered if I might be such an agent. Which might have affected our rapport.

Although I shared his and Doug’s doubt that Oswald had acted alone, to me the idea that our little paper, with no full-time reporters and circulation of a few thousand, could find out what really happened in Dallas on November 22, 1963, was beyond quixotic. We had enough trouble just trying to cover City Council meetings.

The office was chaotic, a walk-in clubhouse for lefties and assorted grievance bearers seeking an audience, plus music promoters and the occasional musician. The great guitar stylist David Bromberg walked in one day to publicize his appearance at a Dallas club, and I interviewed him without getting up from my desk. One book reviewer who specialized in philosophy held court regularly. We got academics and poets in sunglasses and athletes who had just discovered the night before they were destined to write a column. The burly leader of the Bois d’Arc Patriots, a community organizing group, barged in one evening and threatened to tear up the office if we didn’t do a story about affordable housing in East Dallas. Gene the Wino sat around explaining how some of Dallas’ most prominent families were using electronic equipment to monitor his brainwaves.

Meanwhile there was a lot of work to do and not enough people to do it. We relied on strangers walking in the door with an edgy or outrageous story that would not get a hearing in the mainstream media-—like the massage parlor worker who had written a tell-all account about exactly what went on there (“For $25 extra, I’ll use my mouth”) and the airline pilot who brought evidence he was being spied on and harassed for his public opposition to the nuclear power plant being built at Comanche Peak, southwest of Dallas. We went inside a Dallas swingers club and published letters from a Mexican jail sent by a young gringo claiming he had been framed for drug possession in an extortion scheme. As a tabloid, we needed eye-catching or sensational cover stories like this every week, and I tried not to care that some of them might not qualify as classroom material at the Columbia School of Journalism.

I was writing some of these stories and unsure if, at 26, I was developing my skills as a journalist or being held prisoner in the office of an underground newspaper. The pressure to come up with enough copy every week was punishing, plus I had to manage the freelancers and pull an all-nighter every Tuesday getting the paper out. All this left me little time to think of ways we were going to turn the Iconoclast into the Village Voice of Dallas, the recurring mantra heard in the office.

Maybe the revolution was over, but the paper’s history of persecution by the authorities was not, it appeared. One day a documented FBI informer and agent provocateur showed up to sell ads. Danny recognized his face from photos the Iconoclast had run during the trial of “the Gainesville Eight” two years earlier in Florida, where our would-be ad salesman had testified as the government’s chief witness against a Vietnam Veterans Against the War group he had infiltrated and tried to goad into violence. It was hard to believe the government cared about the humble Iconoclast, but on some level this FBI agent trying to come on staff proved that Doug’s and Danny’s paranoia was not entirely unfounded. And caused me to wonder, yet again, what had I gotten myself into.

With Milner gone, I had picked up the story of Willie Nelson as best I could, recognizing the progressive country movement as something authentic and new that an alternative weekly could cover better than the dailies. Willie had become a guitar-plucking, weed-puffing sage and shaman, and when his next three-day, star-studded “picnic” arrived in July, staged on the grounds of a raceway near College Station, I went down with a pack of correspondents to document it. Not long after we arrived and were making our way toward the music along with other celebrants, we passed two parked cars on fire, thick black smoke wafting into the cloudless sky. Oddly no one was doing anything about it, as if the cars were just a ritual sacrifice at this tribal rite for long-haired Texans worshiping under the death rays of midsummer sun. We devoted most of an issue to the event and ran a cover photograph of the crowd, featuring a bare-breasted young woman atop a man’s shoulders, hoisting a longneck Lone Star.

With national political columns by Jack Anderson, Ralph Nader, and Nicholas von Hoffman, plus arts reviews and articles by young SMU professors and future media mainstays David Dillon, Glenn Mitchell, and Rod Davis, the Iconoclast in a given week offered an entertaining, alternative view of the arts and current events not available in the News and Herald. But in 1974 Dallas, that was not enough—not enough to pay the bills, anyway.

It cost a quarter and was available in coin boxes around the city and from street vendors, but the circulation figure was anyone’s guess, somewhere south of the 10,000 Baker liked to quote, always mentioning the “pass-on rate” when anyone questioned the number. Doug and I shared the goal of wanting the paper to “make it” but not the same vision of how to get there. Doug was a good soul and earnest to a fault but uncomfortable with the humor and satire I thought gave readers another reason to pick up a copy. There was often tension between us, and when my paychecks started to bounce, I wondered how long I could stick with him. Ever the thick-skinned businessman, he would nonchalantly instruct me to wait a day and try depositing my check again.

He had found a few liberal benefactors to help him over the humps, and at least one of them was unhappy we were not breaking big stories of scandal and political corruption. True enough, but we lacked the resources such stories required. We could review X-rated movies and print Jerry Jeff Walker’s profane answers to interview questions, but we were not going to expose the hidden power of the oil industry—not paying 50 cents a column inch.

Taffy Cannon, a future novelist from Chicago, walked into the office one day offering to contribute her observations about cherished Dallas institutions such as debutante balls and gun shows. She was talented, and, after a few spec pieces, I convinced Doug to put her on staff at a minimum salary. Reluctantly he agreed, but then her paychecks started to bounce as well.

I hesitated to leave because it would mean Dad having to give up the anonymous column he was writing (for free) with such pleasure and skill, skewering the News, Nixon, religious zealots, management consultants, and other targets that H.L. Mencken would have found worthy. Ah, well. Owed several weeks back pay at the end of August, I submitted my resignation.

A few years later, director Joan Micklin Silver (who had worked at the Village Voice) made a lovely film about an alternative weekly called Between the Lines, with John Heard, Lindsay Crouse, and Jeff Goldblum as the rock critic. It was set in Boston but looked charmingly familiar to me and I’m sure to anyone who ever worked at a paper like this. Removed from real-life deadlines, drudgery, and economic pressures, an underground newspaper could look noble, romantic, and even fun on film. Which I took to be proof that the brain manages not to remember some forms of pain.

I kept the apartment on McFarlin, an upstairs one-bedroom in what had been a roomy Spanish Revival house, with an outdoor entry through a white stuccoed arch leading to a set of paved stairs and a Monterey-style balcony. When a new landlord bought the property, the rent doubled, to $200, but it was still a bargain. I would live there for another seven years and remain ever grateful to Doug Baker for making that possible.

This story originally appeared in the June issue of D Magazine with the headline, “Notes From The Underground.” Write to [email protected].