The Dallas Arts District is a proud statement of progress and achievement in a great American city. It covers twenty square blocks in the city’s downtown, and its architecturally significant buildings are home to the Dallas Museum of Art, the symphony orchestra, opera, theater center, ballet, black dance theatre, chamber symphony, youth orchestra, and other organizations devoted to the fine arts. It also contains museums of nature and science, sculpture, and Asian art.

The district claims to be the largest contiguous urban arts center in the United States—perhaps only New York has as much culture crammed into an area of similar size—and it boasts elegant restaurants and shops, green space, churches, and a high school for the performing and visual arts. The surrounding residential and commercial real estate has risen in stature over the years, and in price, and the district is high on every list of places visitors to Dallas should not miss.

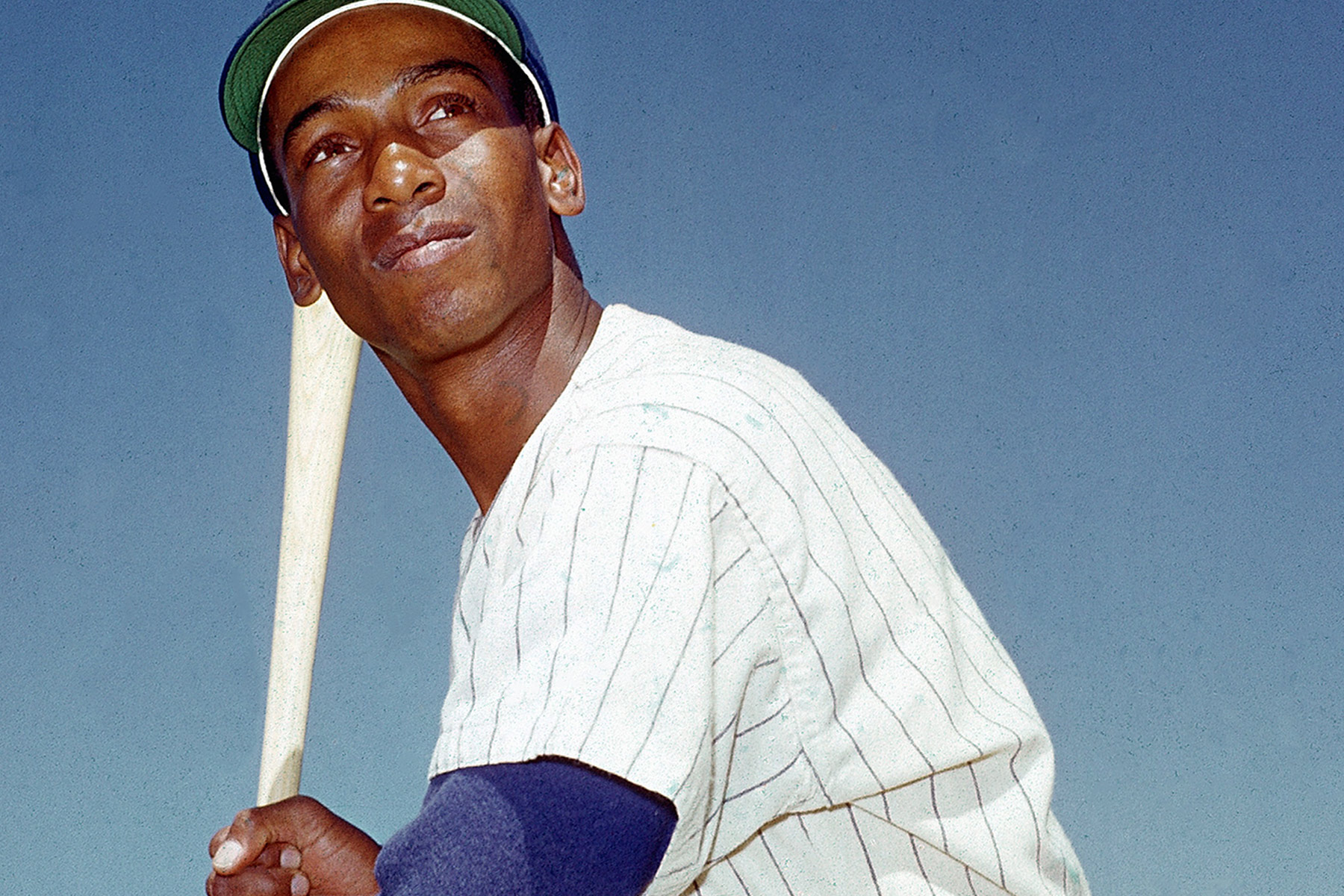

Longtime residents of Dallas and civic historians marvel at the area’s transformation into one of the city’s finest areas from one of its most abject. Though the construction of the Central Expressway in the 1950s destroyed the original neighborhood and makes precise calculations difficult, John Slate, the city’s archivist, believes the arts district sits on ground that after the Civil War was part of an area known as Freedman’s Town. Slate can be sure, however, that the Dee and Charles Wyly Theatre, a building designed by the world-famous architect Rem Koolhaas, now occupies the site of a wooden house of uncertain vintage where, on January 31, 1931, Ernie Banks was born.

Life was precarious for recently freed slaves in and around Dallas after the Civil War. Some gathered in Freedman’s Town near a slave cemetery outside the city limits, where they sought mutual protection from their former owners, who had not taken kindly to the war’s outcome. Though residents of Freedman’s Town who crossed into Dallas risked being arrested for vagrancy, the area served as a source of labor, particularly women working as domestics in white homes, for more than a hundred years. Nor would many other things change for the city’s black residents during the coming century.

Dallas’ schools remained segregated, of course, and black children often used textbooks discarded by their white counterparts and were taught by teachers paid far less than their white colleagues. Streetcars and buses, restaurants and water fountains, movie theaters and cemeteries were also kept separate. There were no black policemen, judges, or city officials, and black voters were barred from the Democratic primaries, the only elections that mattered. During the 1920s, the Dallas chapter of the Ku Klux Klan, whose membership included judges and city officials, boasted that it was the largest in the country. Many areas downtown were forbidden to blacks, and the state fairgrounds were off-limits except on Juneteenth, the black holiday celebrating the end of slavery, and the second Monday in October, which some called “nigger day at the fair.” The practice continued until 1960.

Still, there were opportunities. The coming of the railroads in the 1870s provided good jobs for black workers laying tracks and as conductors while others prospered as farmers. Though blacks were for the most part not allowed to own property, white entrepreneurs bought cheap land on both sides of the Houston & Texas Central Railway tracks and built rickety houses to rent to them. Some of these areas remained unchanged for many years.

A survey conducted by the Dallas Housing Authority of the city’s black districts in 1938, for instance, cited the lack of sanitation, absence of sunlight, leaky roofs, broken and boarded-up doors, and sagging floors and walls in most of the houses, and called them “unfit for human habitation.” “Fire hazards in these areas endanger the entire city,” the report concluded. “The insanitary conditions threaten the lives of the people as a whole, especially in the event of an epidemic. The depressing effect of the slums on the morale of the inhabitants of the areas endangers the social stability of the entire community.”

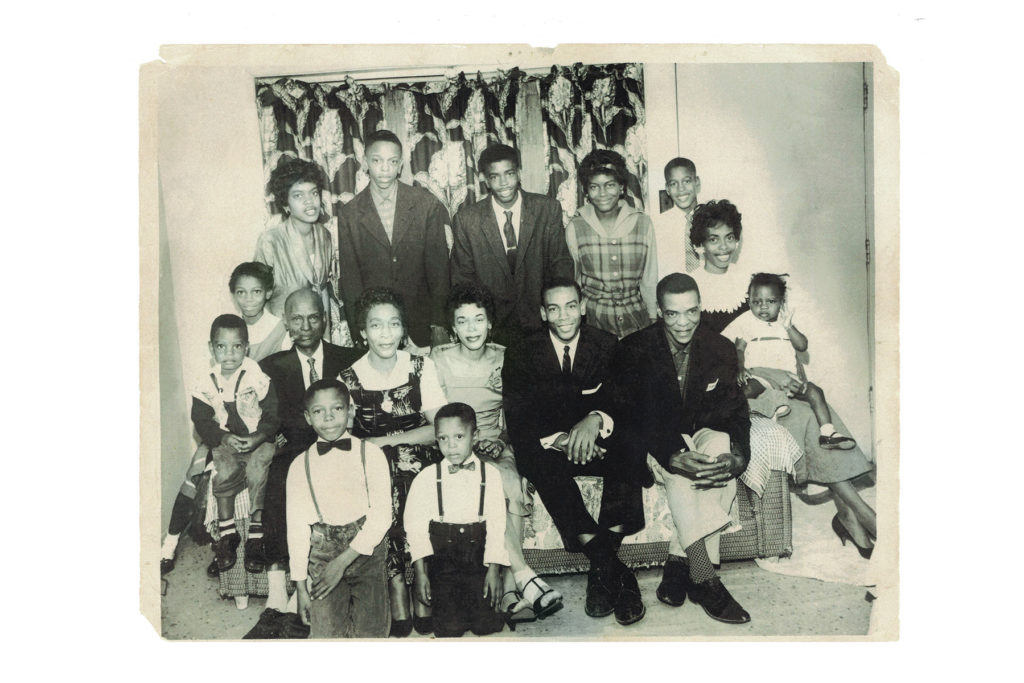

To Eddie and Essie Banks and their growing family, it was home.

“There were three rooms from the front clean through to the back— a front room, a middle room, and a kitchen,” says Edna Warren, the first of the Bankses’ 12 children, of the family home at 1717 Fairmount, which they rented for 20 dollars a month. “There were double beds in each room and there were always two or three kids in each bed.”

There was no indoor plumbing, just a faucet behind the house where the outhouse was also located. To wash dishes, Edna took a dishpan outside, filled it with water, brought it back in, and heated it on the stove. To rinse them, she repeated the process. Baths were taken in a big iron tub, which was also filled with water and heated on the stove. The laborious process restricted baths to one or two a month.

Essie Banks supervised laundry day in the backyard, using what she called a boiling pot, lye soap she made out of fat, and a “rub board.” She pushed the clothes through the water with a stick, then transferred them to another pot, where Edna rinsed and hung them on a clothesline. Ironing was done with a smoothing iron, a flat piece of metal that was placed on the stove until red hot. What light there was inside the house came from kerosene lamps with glass chimneys containing small wicks. “I was the chimney girl,” says Edna, whose job was to keep them clean.

As a treat for his ever-growing number of children, Eddie would sometimes string three or four extension cords together and give a quarter to the woman in the house next door, which had electricity, and they would listen to the adventures of Superman, Batman, and The Shadow on an old

radio the woman had given them. When Eddie ran out of quarters, the radio fell silent. Not until Essie, during a brief respite from having children, took a cleaning job at the Dallas Medical Center could the family finally afford their own power. “It was an event to be remembered when we switched from lamps to electricity,” Ernie Banks would recall.

The house was heated by two wood-burning stoves fueled by large logs provided by the WPA, the New Deal agency whose trucks also delivered flour, meal, cheese, corn, and other staples, and occasionally used articles of clothing. The logs would be sawed into chunks, and by the time Edna was 10 years old her father had taught her how to split them with his double-bladed axe into four pieces small enough to fit in the stove. Why, she wondered, was it her job and not that of her brother, who, though he was two years younger, was taller and stronger than she was? “Daddy, I’m a girl,” she complained. Eddie Banks pointed out that Ernie had other chores, including carrying the chopped wood inside, and that everybody had to contribute.

Feeding the family was a challenge. Essie grew greens in her backyard garden and made biscuits and small round tea cakes that Ernie particularly enjoyed, using lard instead of butter, and powdered eggs, and filling them with syrup and jelly. By far the biggest staple of the Banks family diet was red beans, which came in 50-pound sacks. “My mother was a genius with money,” Ernie would remember. “She could make a little bit of money talk. She would take a big can of lard, a big can of beans, a big can of flour, and fix the same meal for months.” Still, a boy could get tired of beans, and once he had money of his own he never ate them again.

One source of bounty was a nearby Safeway where the men stocking its shelves would let out a whistle signaling that deliveries were being made. Neighborhood families would wheel wagons around to the back and go through crates of rotten and bruised fruits and vegetables. “If they would get a truck in with grapes, maybe a few of them on the top would be rotten, but they’d get rid of the whole crate,” says Edna, who, along with Ernie and their younger brother Ben, was part of the pickup crew. “Mama got rid of the bad part and we ate the good part. Then she would take the rotten grapes and make jelly out of them.” Wednesday was chicken-delivery day and Essie would ask for the feet, and perhaps some neck bones and pig’s feet that were about to be thrown out.

This foraging once had unintended consequences for Edna. When she and Ernie were attending Booker T. Washington High School, which was diagonally across the street from their home, one of her teachers paid a surprise visit. “I saw you at the garbage can the other day,” the woman said. “I’m going to give you and your brother tokens for your lunch so you won’t have to be out there doing that.” Mortified, Edna tried to explain the food wasn’t exactly garbage, but the teacher was unmoved. She would be getting a free lunch now. She should stay away from garbage cans. The story quickly spread through the school, and she began hearing catcalls from her classmates—“I heard about y’all digging through garbage cans”—and her humiliation increased. Nor did she understand how Ernie, who was as much an object of the taunts as she was, could simply ignore them. Why didn’t he ever get angry? she wondered. Why didn’t the way they lived bother him as much it did her? Why did she sometimes have the feeling that black people didn’t have anything to live for, while her brother just shrugged it off?

Ernie would always remember these days with fondness. The rusted wheels he found that he attached to a scooter he fashioned out of boards and raced through the neighborhood with his friends. The BB gun he used to shoot rats, which were never in short supply. The prom jacket his mother bought for 50 cents at Goodwill and his date, a girl named Judy, leaving the dance with somebody else. Miss Della, who lived across the street and sat in a rocking chair on her porch all day, watching him when he went to school and again as he came home. As an adult, he would enjoy rocking chairs himself, and he would think of Miss Della whenever he sat in them.

There was also the Thanksgiving Day chicken his mother left in the backyard while she fetched a pail of boiling water after wringing its neck. When he was sent to retrieve it, there was nothing but a trail of blood. Ernie told this story in different ways over the years; its most colorful version has him following the blood to the thief’s lair and, after a wrestling match, returning triumphantly with the chicken intact and his clothes torn and bloody.

“I never said, ‘Why do they have that and I don’t?’ ” he said many years later. “We didn’t look at other folks. We just lived for the moment and had fun.”

“We didn’t know we were poor,” says Ernie’s childhood friend Jack Price. “We didn’t know we were living in shotgun houses. We thought outdoor facilities were the norm. We just accepted it.”

Banks never entirely overcame this part of his childhood. “I don’t look forward to too much,” he told an interviewer in 1963. “Even now, I haven’t geared myself to extreme heights because of the way I was brought up. I was taught that whatever I had, to be happy with it—even if it was a small thing.”

Edna felt different. “I was tired of hard times,” she says. “I was tired of being neglected, of people looking at us as poor WPA kids.” She and her brothers and sisters had been taught to do without, to accept being poor, not to nag their parents for things they couldn’t have. She had heard her father’s stories about when times were really hard—about soup kitchens and bread lines when the Depression was at its worst. And besides, they were a family, with a mother and a father who loved them, did their best for them, and, poor or not, were respected in the community. “His father, all of them, were very nice people,” says Dr. Robert Prince, one of Ernie’s classmates. “Ernie may have been poor, but he was one of the nicest, most respectable young men around.”

in 2013, not long after Scott Rudes moved from Tampa, Florida, to Dallas to become the principal of the Booker T. Washington High School for the Performing and Visual Arts, he received a call from the city’s mayor, Mike Rawlings.

“Scott,” Rawlings asked, “who’s the most famous alum of Booker T.?”

Rudes knew the school had produced many well-known musicians and artists since becoming an arts magnet high school in 1976. Among them were Norah Jones, the pop and jazz icon who had won multiple Grammy Awards and sold tens of millions of albums; Erykah Badu, the singer-songwriter whose work spans multiple genres; Roy Hargrove, the celebrated jazz trumpet player; Edie Brickell, the popular musician and singer who would write a Broadway musical; and other writers, actors, artists, and film and television directors and producers.

Rudes also knew a trick question when he heard one. “Ernie Banks,” he said.

“Good,” Rawlings said. “You passed the test.”

Visiting art, drama, and music teachers from around the country entering the gleaming new wing of Dallas’s performing arts high school might find themselves weeping with envy. The dozens of girls lined at the ballet barre, the art gallery of students’ work, the photos of students painting, sculpting, tuning violins, applying theater makeup, and peering through microscopes: together, they present a statement of aspiration and accomplishment, of the best that a public high school education can offer.

Intensely competitive in its admission process—all students must submit a portfolio, play an instrument, perform a monologue, or provide other evidence of their talent—Washington admits only about one in four applicants and their highly credentialed teachers are supplemented by a noteworthy support group. “There’s not a place in the Dallas Arts District that our students don’t use,” says Sharon Cornell, the school’s publicist, of its interaction with the surrounding museums, theaters, galleries, and performance halls. “Every arts organization here has an influence on our students. We’re like their little brothers and sisters.” Surveying the school during a visit, the singer and musician Harry Connick, Jr., called it a Willy Wonka factory for artists.

But Washington also has another less exalted wing, which was built in 1922 and is connected to the bright and airy new addition. It is where Ernie Banks went to high school.

Baths were taken in a big iron tub, which was also filled with water and heated on the stove. The laborious process restricted baths to one or two a month.

Long before Dallas’s only black high school received its new name and was moved to its present location, it had a much simpler designation: Colored School Number 2. Many of its students walked five or six miles to reach it, often passing white schools closer to their homes. Counties outside of Dallas that didn’t have high schools for black children bused them to Washington and later to Lincoln High School, which opened in North Dallas in 1939. When Dallas’ schools were desegregated in 1969, Washington was closed and the building was used for storage until, in an extraordinary act of civic imagination, it became an arts magnet high school.

Homes like those the Banks family lived in were long gone by then, and the area consisted of parking lots, liquor stores, and the occasional barbecue shack. White parents had their doubts about sending their children to this part of town, and powerful forces in the city wanted the new school located in the city’s more upscale Fair Park area. But in the end it was placed in the refurbished Washington building, and over the years it was joined by other arts institutions and became a part of the Arts District.

The original wing of the building is an architectural misfit among the modern structures that surround it. Its redbrick façade is indistinguishable from elementary and high schools of a certain era all over the country, as are the narrow hallways lined with lockers on both sides and lit by rows of large single fixtures descending from the ceiling on long poles. A trophy case commemorating past glories lines one wall—the school no longer competes in interscholastic sports—and in one corner there is a glass cabinet that contains a tribute to Ernie Banks. The sense of new connected to old continues in front of the original wing where girls in leotards take yoga classes in the late-morning sun. The plot of grass they sit on, which is divided by a cement walk leading to the front entrance, is where Banks and his grade-school friends first played football.

“It was the only grassy area in the neighborhood,” says Jack Price, who would go on to play football at Washington with Banks. “The sidewalk was out of bounds so we called time and moved over to the grass, but somebody would always try to get in a good lick. When we played football in high school we practiced on gravel and dirt—I still have scars on my hands—but when we were kids playing by ourselves we had this nice green grass.” Since none of the boys could afford a football, an empty tin can of the approximate size had to do. “You had to know how to catch the can just right or you could cut yourself,” Price says.

The boys found another unlikely practice field on a lot at a pecan shelling factory behind Banks’s home on Fairmount Street. After the nuts had been removed, the shells would come flying out of a chute and form their playing surface. The only thing that could stop the action was the discovery of a nut that hadn’t been opened, which was quickly eaten. “We’d be all raggedy and dirty and Mrs. Banks would come out of the house and say, ‘Get out of those shells,’ ” Price says. “ ‘Come on in. Look at your clothes. Jack, you go on home and wash your clothes. Ernie, you come over here and wash yours up.’ ”

North Dallas might have been poor, but it had its own set of rules about raising children that were not to be trifled with. Rule number one said any adult could discipline any child at any time and that the miscreant’s parents would back them up. “You knew that if you got in trouble somebody would go tell your mama,” says Joe Kirven, another of Banks’s future football teammates at Washington. “The last thing you wanted to hear was ‘Boy! Stop doing that!’ because you knew they were going to tell your parents.” This community watch system could also work to a child’s advantage. Gloria Foster, Kirven’s wife, remembers when a classmate jumped her on a sidewalk and Gloria rolled on top of her and held her down. Luckily, a woman across the street had seen the incident and spread the word. “Before I could get home, she had called my mother and explained what happened,” Gloria says. “Otherwise, I would have been in big trouble for fighting.” Since many Washington teachers lived in the neighborhood, they were on unofficial duty away from their classrooms. “They would be up and down the street watching,” says Price. “Even on weekends when school was out. You never got away from them.”

A few years later, when Banks and his friends exchanged their tin cans for real footballs and joined Washington’s team, they found themselves under surveillance by men with a more nefarious interest in their welfare. As far back as the 1870s, gambling had been a major factor in the Dallas economy, and city historian John William Rogers notes that efforts to outlaw the practice were considered bad for business. When a zealous district attorney moved to drive gamblers out of town, “a delegation of businessmen called upon him to point out how ill-advised such a move was for the [city’s] prosperity and that Fort Worth with a shrewder policy was offering the gamblers free rent and $3,500 to remove to that city.”

Such Wild West leniency was long gone by then, but gambling was still pervasive in North Dallas and everyone knew who the gamblers were. “They’d come up to you and say, ‘Hey, didn’t I see you wearing that uniform?’ ” Price says. “ ‘It’s 9 o’clock. What you doing out this late? Get off these streets. I’m going to tell the coach. I’m going to tell the principal.’ Then he’d turn to his friend and say, ‘He’s out here losing my money.’ There was no such thing as hanging out at night. They would run you home.”

The players took these and other warnings seriously because they knew their neighborhood’s dangers. White people hardly ever ventured into their part of town and the few brave souls who did were wary. Edna recalls the man who regularly brought his laundry to her mother and waited outside until it was ready. “He wouldn’t come in and sit down,” she says. “Mama would go to the fence and hand him his clothes and he would get in his car and leave.”

Guns, drugs, alcohol, and theft were a constant presence in North Dallas, and Ernie was well aware of them. One of the first business transactions he ever witnessed was in a pawn shop where his friend Rastine Goodson sold watches and rings that Ernie suspected belonged to his mother. When Ernie returned home from the army some years later, he was not surprised to learn Goodson was in prison for selling drugs. Ernie ran with Rastine and his larcenous friends for a while, but more as an observer than a participant.

“They’d come around the house and say, ‘Come on, let’s go,’ ” he recalled years later. “I’d go with them, but I always backed away from trouble. I can’t explain why. They’d look around and I was gone.” Banks would retain this quality of disengagement throughout his life—“I don’t like arguments, confusion, drama,” he said. “It’s just the way I am”—and he never forgot how much it amused Goodson. “You’re Casper the ghost,” his friend told him. “When things happen, you’re like smoke, you’re gone.”

Goodson told him something else during their wanderings, too, and when many of his friends and family members were ravaged by drugs or met early deaths, Ernie never forgot it. “He said I was a blessed child.”

Excerpted from the book Let’s Play Two, by Ron Rapoport. Copyright © 2019 by Ron Rapoport. Reprinted with permission of Hachette Books. New York, NY. All rights reserved.