A few minutes before 9 am on a warm Saturday in late May, I’m standing with about a dozen strangers in the middle of the West Texas desert. We are on the edge of Seminole Canyon, about a half mile north of the Rio Grande. In the canyon below, along the towering limestone cliffs, are the faded remnants of painted images—shamans, worshipers, strange creatures, structures, symbols, and incomprehensible hieroglyphs—that were made by the people who roamed this sparse landscape for millennia before disappearing into the obscurity of history.

I’ve wanted to come here for years, drawn, in part, by my interest in art and history, but also by some other more vague and possessive force. Seminole Canyon is one of the world’s most rare and peculiar museums. Some of its paintings are 9,000 years old; the more recent ones are around 500 years old. They are all expressions of people whose lives, habits, values, and religious beliefs and practices are unknown and will always remain so. Archaeologists can only guess at the paintings’ meanings. Perhaps they are the exuberant markings born of some mystical ritualistic trance, or an anthology of a long-forgotten mythical tradition.

It’s that ambiguity that lures me, the idea of encountering something simultaneously so intimate and yet so alien, the desire to stand in front of something that can’t be known. What I could have never expected, however, is that at the bottom of the canyon I would also encounter an artist from Dallas named Forrest Kirkland, whose culture and history is less obscure but whose genius has been similarly forgotten and lost over time.

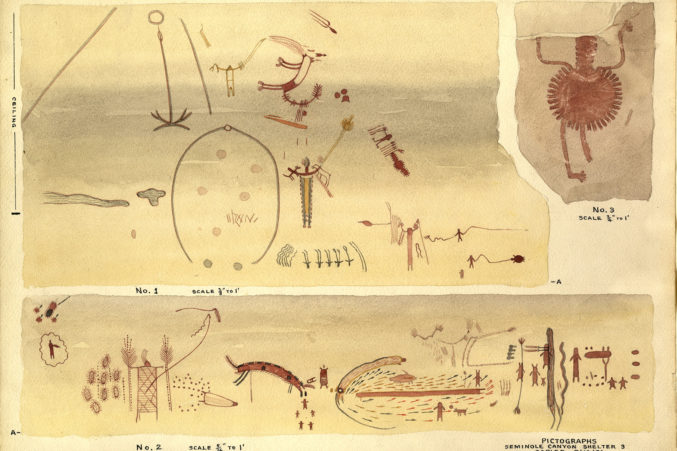

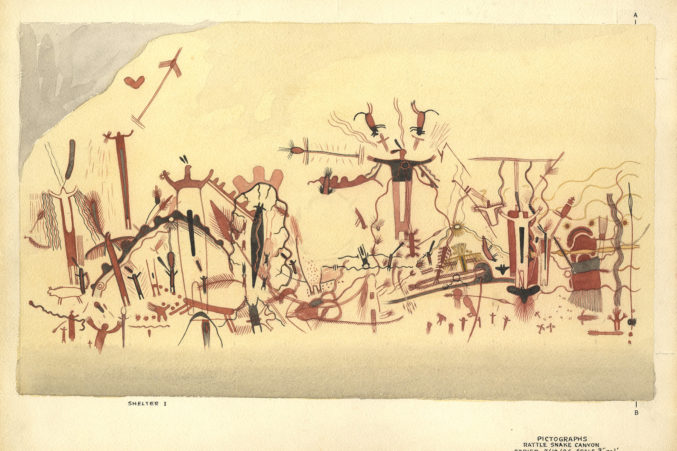

We are led by a park guide down a narrow walkway that leads to a creek and then back up to the ledges that form shallow caves above the canyon floor. The walls of the caves are covered in painted figures and bizarre abstract forms that tower over soft, pock-marked ground still strewn with shards of woven fiber.

A marker contains a reproduction of a painting of this spot that allows the curiously ignorant observer, like me, to decipher the images from the rock—images that are now fading fast because of pollution and increased humidity caused by the nearby Amistad Reservoir. The painting of the cave was made, the marker says, by Kirkland.

Olea Forrest Kirkland was born in 1892 in the tiny town of Mist in the flats of the Arkansas delta. After training as a commercial artist in Michigan and fighting in France during World War I, Kirkland settled in Dallas, where he set up a studio that specialized in producing mechanical drawings for industrial firms. In the 1920s, there was plenty of work for a commercial artist in Dallas. The city was undergoing a period of rapid urbanization, transitioning from a cotton and railroading town to a financial center of the burgeoning oil industry. As Kirkland’s firm thrived, the artist also painted watercolor landscapes in his free time, often choosing as his unlikely subjects the overcrowded Dallas slums.

In 1933, however, Kirkland stumbled upon an obsession that would consume the next decade of his life: the indigenous rock paintings that lined the walls of not only Seminole Canyon, but dozens of canyons and caves throughout his adopted state.

Kirkland possessed an amateur’s curiosity in archaeology. He fished for arrowheads that were then easy to find in the creek beds and tributaries of the Trinity River. He would become the founder and president of the Dallas Archaeological Society. But it was at a family fish fry on the Llano River in 1933 when his father, noting Kirkland’s interest in art and artifacts, suggested he check out the indigenous rock paintings along the Concho River, west of San Angelo. The following year, Kirkland and his wife, Lula, made their first trek to Paint Rock, and the artist completed a few hastily sketched watercolors of the rock art. At first, Kirkland saw his paintings simply as an addition to his amateur collection of Native American artifacts. But something about the watercolors took hold of him.

“Every time I looked at these copies which we hung in our little museum, this question came to mind: why shouldn’t I return to Paint Rock and carefully copy every picture still remaining on the cliff and so save them for future generations?” Kirkland wrote.

After some research, Kirkland discovered that such a survey of Texas’ rock art had never been attempted. Kirkland returned to Paint Rock the following summer and made more careful copies of the art he found there. Kirkland and his wife then set out to scour the state in search of rock art. In their rickety 1936 Dodge sedan, they drove thousands of miles of dirt roads to hard-to-reach, unexplored canyons all over Texas, completing hundreds of watercolor copies of the ancient art, meticulously rendering each to scale and precisely logging locations and styles.

The paintings Kirkland created of Texas rock art represent the largest and most comprehensive catalog of indigenous imagery ever created, and it is collected in the book The Rock Art of Texas Indians, which was published in 1967 and is available at the Dallas Public Library. In some cases, Kirkland’s paintings are the only remaining document of rock art that has been lost through erosion, fading, or the flooding of canyons by the construction of dams and reservoirs. In other cases, researchers rely on Kirkland’s paintings to study rock art located on off-limits private land. Because of this, in the world of Texas archaeology, Kirkland’s name and work are widely known. But in his adopted home of Dallas and in the world of Texas art, he is all but anonymous.

Kirkland died of a heart attack in 1942, at the age of 49, after completing his final watercolors at a site south of Fort Chadbourne. In just eight years, he had accomplished his goal to save indigenous rock art “from total ruin.” And yet, I can’t shake the feeling that there is something else going on in his work that transcends its value as archaeological record.

On the way back to Dallas, I stop at the University of Texas at Austin’s Texas Archeological Research Laboratory, housed in a nondescript, corrugated steel warehouse on the J.J. Pickle Research Campus north of town. Jonathan Jarvis, the lab’s associate director, leads me into a cramped climate-controlled archive room, where he takes down two white archival boxes from nearly a dozen off the top of a file cabinet and opens them on a table. Inside is the entirety of Forrest Kirkland’s oeuvre, hundreds upon hundreds of watercolor paintings, a body of work that painstakingly re-creates every inch of rock art that is known to exist in the state of Texas.

I’m allowed a few minutes to flip through the paintings. In person, you can appreciate the attention to detail and color, how the man whose professional life was spent rendering with precision the exact inner workings of complicated machinery applied the same exacting standards to making these copies. You can feel something of Kirkland’s personality come through, obsessive yet restrained. In their abstraction from rock onto paper, the paintings that were layered on top of each other over many thousands of years become something different, neither new creations nor pure copies.

I place the lids back on the boxes and they are returned to the top of the file cabinet in the refrigerated room in North Austin. Back on the road to Dallas, retracing a route the Kirklands must have taken dozens of times, it occurs to me that Kirkland’s watercolors are a lot like the rock paintings themselves. They, too, are artifacts. They are a response to a desert encounter. They suggest the motives and mysteries that shaped the life of a great Dallas artist.

They tell a real but ultimately incomplete story of a man who has been inevitably lost to time, but whose spirit’s indelible mark remains.