On my first night of living in Dallas without a car, I’m chilling at Griffin and Commerce, and I’m expecting mean streets. Four blocks away, the West End is still party central, but here at the grandly denominated Central Business District West Transit Center—a bunch of canopied benches erected in front of a vacant parking lot, between the Greyhound station and the downtown McDonald’s—there’s a film-noir vibe, with splashes of yellow light from the street lamps and the rustle of discarded Spanish-language newspapers tumbling toward the ghostly federal building.

Two black guys swagger toward me, one a beefy, jowly linebacker type with his hands in the pockets of a North Face parka, the other a beanpole wearing a Texas Longhorns t-shirt about 9 yards long.

“Are you cool?” asks the beanpole.

“I’m cool,” I say.

They stop in front of me.

“You like rap music?” asks the same guy.

Because I can’t see where he could possibly be concealing any CDs that he’s about to offer me for 10 bucks each, I say, “I only like Ice-T.” (The reason I like Ice-T is I once interviewed him on a TV program, and he’s the only rap artist I’ve ever sampled.)

“Ice-T, huh?” He seems to be considering my answer. Then he grins broadly. “Old school!” And he raises his arm to offer a soul shake.

I’ve never been able to do the soul shake, but I go ahead and give it my best shot. After a few exclamations about “Body Rock,” “Dog’n the Wax,” and “Iceapella,” I offer the homies cigarettes and they saunter off toward the McDonald’s.

Later on, I’m joined by a bus rider with a gaunt Lee Harvey Oswald look, and he asks me what we were talking about. “They wanted to talk about music,” I tell him.

“They asked you if you like rap music?”

“Yeah.”

“That’s just the line they use on white people.”

“Why?”

“They were f—ing with you.”

“Well, they seemed to know a lot about music.”

As a person with some experience of being f—ed with, it was about the least-menacing f—ing-with I had ever encountered, but I chalked it up to the mythology surrounding the CBD West Transit Center, known far and wide as “the Mickey D Stop,” notorious for being the most thuggish hangout on the entire DART system. At the Mickey D Stop, every little interchange between strangers is apparently invested with dark meaning and suspicious motives.

During the next week, I would return repeatedly to the Mickey D Stop and, after a while, start eating in the McDonald’s, because DART is ridiculously devoid of food at most transfer points. After three days, I knew pretty much all of the local characters, including Jack Henderson, a lithe, wiry comedian who always dresses in a Cowboys shirt and cap and whose particular talent is jerking down the sidewalk with the gait of a mental patient. He’s not schizophrenic, just setting you up for his request for “13 cents for a hamburger.” (“I’m hungry, man. I’ve got the rest. I just need 13 cents to go in McDonald’s.”) How he fastened on 13 cents as the optimal begging denomination, I was never able to figure out, but I would usually just give him a cigarette—which, come to think of it, is worth way more than 13 cents—and he would respond with the soul shake. These guys never struck me as thugs so much as performance artists, and I got to where I looked forward to mixing among the stock company every day.

What I was finding out is that it’s not only possible to live in Dallas without a car, it’s energizing. Dallas doesn’t have street life in the way that, say, Kiev does, but inside the buses and trains there’s a bizarre human comedy being played out incessantly. For three days of my carless week, every train between Pearl Street and the Convention Center was packed with high school students in natty royal-blue blazers, delegates to the annual meeting of DECA, which stands for Distributive Education Something Something and involves some kind of “I want to be an entrepreneur” course of study that seems to be popular in the remoter regions of Kansas and Montana. (Here’s a shout-out to Margie and Ron! Forest Hills rules! Represent!) On another day, I engaged in theological discourse with a glass-eyed street preacher who was able to quote scripture all the way from Park Lane to the West End. I only remember his last words: “The Lord don’t make no mistakes. I make mistakes and you make mistakes, but the Lord, he don’t make no mistakes.” There’s something about those trains that makes people expansive and communal, in a way you don’t find much at, say, the mall. Spanish helps, too. If you’re uni-lingual, you’re missing half the show.

Mass transit in the city has two anniversaries right about now—10 years since the light rail opened and 50 years since the last streetcar was put out of commission—and my quest was to see just how practical the system had become. I’m a train buff myself and an inveterate user of transit systems, having mastered at various times the route maps of New York, Copenhagen, Paris, London, Los Angeles, Chicago, New Jersey, Long Island, Boston, San Francisco, and other cities where I’ve spent some time. I’ve traveled just about every route on the Amtrak system, including, of course, the dismal, beleaguered Texas Eagle, which departs from Union Station twice a day on the Chicago-San Antonio line. I consider the Texas Eagle “on time” if it arrives less than three hours late, a state of affairs usually caused either by idling on swampy sidings south of Texarkana while the priority freight trains jockey through the East Texas mixmaster, or else by dawdling in downtown Fort Worth while the Eagle is being serviced. (They have to actually back the train into the station.)

In other words, I’m a weirdo. I was reminded of this repeatedly when I told people I was living carless in Dallas for a week while traveling to various appointments and destinations every day. “I hope you have a good book with you,” said one friend who hasn’t been on a bus since 1972. (I did. In six days I completed the massive Cobra 2: The Inside Story of the Invasion and Occupation of Iraq.)

“Did you check out our Trip Finder on the web site?” asked Morgan Lyons, the peppy and personable press rep for DART, when I told him of my quest.

“Yeah, it doesn’t work.”

The online Trip Finder lets you type in a destination so that you can get the easiest train and bus routes. But it won’t give you the route unless it’s within three-tenths of a mile of the final stop.

“You need to make that a mile in some cases,” I told Morgan. “The computer can’t find stuff in Bent Tree and places like that.” He seemed skeptical. “What’s a mile?” I said. “Ten minutes walking time? Three minutes on a bicycle?”

“Nobody walks 10 minutes in Dallas,” was Morgan’s reply. “They wanna be dropped off at the door.”

So I stopped using the Trip Finder after the first day. There are really only three things you need if you want to make DART your only means of transportation. The first is the DART System Map, which must be some kind of minor milestone in cartography, displaying, as it does, every single route of every single bus and train in the entire region. It’s so detailed you can pretty much plot out where you want to go without even bothering to get a formal schedule. Yes, you run the chance of having weird connections, but my practice of just jumping onto the nearest bus or train and assuming the next leg will be there waiting for me worked about 75 percent of the time. (Worst-case scenario: buses in north Plano that run once an hour. Miss the connection by one minute and you end up staring at corporate sculpture for an eternity while not talking to the Salvadoran maids, who don’t wanna test their English on the geek with the backpack.)

The second thing you need is a cell phone, so you can call ahead after that last transfer and tell everybody exactly when you’ll be arriving. You can also use it to call the DART automated guidance system, but I gave up on that, too, after repeatedly ending up at “Press pound to hear this menu again” and having no idea what to do.

The third thing you need is either a day pass (for $2.50) or a premium monthly pass (for $70), which allows you to ride any bus, any train, anywhere, anytime. This is the best fare in the history of transit. To use just one comparison, a New York commuter on New Jersey Transit—cheapest of Gotham’s commuter trains—would pay $198 a month to travel from Ridgewood, New Jersey, to New York Penn Station, which is about the same distance as north Plano to downtown, and his ticket would be good for that line only and those two cities only. Adjusted for inflation, figured at two trips and one transfer per day, the DART monthly pass is better than the Dallas streetcar fare in 1910!

DART is the most socialistic city service Dallas ever came up with. In fact, it’s not unlike the transit system built in Moscow under Stalin, where the infrastructure is massive, the stations are pristine symbols of civic pride, the trains and buses run on time, and the service is almost free. It’s what communism was supposed to be! By the standards of transit systems in other cities, DART should be bankrupt by now. Fares paid for only 11.6 percent of the cost of running it last year, ranking it near the bottom of all transit systems in the country, and yet the cities that subsidize it in the form of a 1 percent sales tax are not only happy with the result—train stations are turning out to be commerce magnets—they’re starting to want more. DART is something of a miracle: a transit system that works, in a sprawling 700-square-mile car-oriented region, paid for by taxpayers that never revolt against the cost! When gasoline hit $3 a gallon earlier this year, DART ridership spiked by 12 percent, and soon the DART board will need to order some more state-of-the-art, one-of-a-kind Kinki Sharyo train cars from Osaka. (The Japanese make those just for us. They’re not used in any other city.)

It wasn’t always like this. Very few people remember Maurice Carter, the first DART executive director in the early ’80s, but he was one of the most despised men in the city, constantly being harangued for the “boondoggle” he was put in charge of. Editorial columnists made fun of him for using the term “light rail.” (“In other words, streetcars!”) City councils thought he was a blue-sky planner type with no sense of what city he was working in. When he finally got fed up and left, in 1984, the new DART management team tried to get long-term financing for a much larger, more expensive transit system. Shot down at the polls in 1989, DART had to rethink its strategy and ended up building exactly what Maurice Carter wanted, one of the finest light-rail systems of the 21st century. Yes, the trains max out at 65 mph, and they hit that speed in only a few places—the downtown subway section, the forests north of White Rock, a stretch of the Red Line in the far north—but it’s interesting to watch the North Central Expressway commuters out the window. They’ll occasionally pull slightly ahead of the train, then suddenly slow to 30 and disappear over the vanishing horizon. Light rail turned out to be plenty of power for the needs of the city.

Still not convinced? Most people north of the Trinity aren’t. When I told my agent, who lives in the Collin County part of Richardson, that I would be coming to see her, she said, “You’ll never find my house. I’ll pick you up at the station.”

“Nope. Against the rules. Besides, that’s what Mapquest is for.”

The conceptual leap she was unable to make was the idea of getting off the train and getting onto a bus. It’s the bus part that stops most people from making full use of the system. The park-and-ride lots on the Red Line corridor are so full much of the time that commuters sometimes drive north to the next station, even when they’re taking a train south, which defeats the whole purpose of a transit system, which is to get rid of the hassle of driving and parking! But the conventional wisdom is that the buses are somehow Third Worldish in a way the train is not. That’s why the biggest secret of the last 25 years of DART development is that the buses are the real Porsches of the system. They’re roomy, comfortable, rarely crowded, clean, quiet, environmentally friendly, and feature the latest in GPS technology that automatically spits out an electronic readout of the upcoming cross street. (The major streets and transit centers are also electronically announced by one of those insanely pleasant female airport voices.)

The buses are the backbone of the system, accounting for 68 percent of the annual passenger trips, including service in places far from the nearest light-rail station, like Lake Ray Hubbard and Carrollton. That ratio will change dramatically between now and 2013, when the light-rail system will double in length, thanks to a just-announced $700 million grant that will kick-start a $2.5 billion expansion. Right now Dallas has a relatively short rail system of 45 miles. (By comparison, the New York City subway system, in a much smaller geographical area, is 660 miles long.)

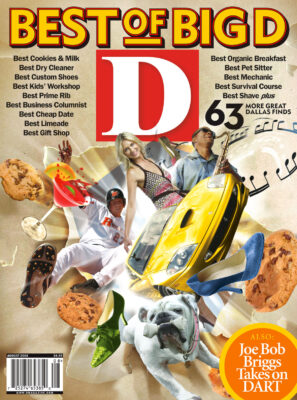

Given that Dallas got a late start—two failed transit initiatives in the ’60s and ’70s, a crushing defeat at the polls in 1989 that forced everyone to start from scratch—I would give the whole system at this point an 8 on a 10 scale. But Dallas is a city of perfectionism. We can do better. As the build-out continues and the apparently inexhaustible 1 percent sales tax keeps churning, the DART board would do well to heed Joe Bob’s 10 pet peeves about DART. Now I’m gonna do what I do best. I’m gonna gripe. If you wanna discuss it further, you’ll have to show up at the Mickey D’s on Commerce.

JOE BOB’S 10 DART DECREES

Joe Bob DART Decree Numero Uno:

Those 30s have to become 20s.

Most men will wait 10 minutes for anything except sex. That’s why I think that every bus and every train should run every 10 minutes. In the few transit systems where this is true—Paris, Copenhagen, most parts of London, and the amazing Moscow system, which runs every two minutes at every station—you never have to carry a schedule, remember a departure time, or worry about a transfer. Of course, the reality in most cities is that no one can afford to run that often. You have to take an immense financial hit in the early stages, as people gradually realize how convenient it is, before the ridership reaches a critical mass that pays for even a fraction of it. It requires bold risk-taking. That’s why I’m setting the standard for Dallas at 20, not 10. If everyone knew the worst-case scenario was a 19-minute wait, I think ridership would spike appreciably. Unfortunately, there are still buses spaced an hour apart. The Trinity Railway Express, between Union Station and downtown Fort Worth, also has some pretty awful frequencies, especially on the weekend, but it’s a more traditional commuter train, so there’s an assumption that people know what time they’re leaving every day and they always take the same train.

Joe Bob DART Decree Numero Two-O:

Lose the sculpture, add the pretzel vendors.

For my trip to north Richardson, I took the Red Line to Arapaho Center Station, walked under the street through a grotto-like tunnel, and arrived at a dramatic piece of outdoor sculpture masquerading as a bus station. Like all the other 15 transit centers, it was a pinwheel design, with bus portals arranged around a central glass building that houses waiting areas, an information desk, restrooms, and two vending machines that are barricaded behind an iron grate. (There’s apparently some major paranoia within DART about potential vending-machine theft, including the theft of the 500-pound machine itself.) These places are a little surreal and often heavily policed. (At the West Transit Center in downtown Dallas, adjacent to the West End, there are always a couple of hundred people waiting, and yet the walls are plastered with “No Loitering” signs.) The DART employees aren’t exactly glad to see you, either. I was never able to figure out whether they’re there to help confused riders or to soothe the nerves of surly bus drivers, but it’s best to avoid eye contact with them entirely. It’s a little like being invited to someone’s 80-room mansion and then being told to sit quietly in the first room you see so that you don’t disturb anything.

The normal services you find at bus and train stations all over the world—coffee vendors, newspaper stands, hot dogs, muffins, Starbucks, Dunkin’ Donuts—are nonexistent at the DART transit centers, even though these places, given some of the wait times, would seem to be an entrepreneur’s dream. No pushcarts, no kiosks, no Louis Farrakhan guys selling incense. The bare essentials you need while waiting—caffeine, empty calories, Us Magazine’s latest report on Brangelina—are nowhere to be found. When I asked DART why, they pointed to Mockingbird Station as an example of commerce thriving around a train platform. And yet, if you wanted to hit the Starbucks there, you would have to take the elevator up from the platform, cross a mini-plaza, descend some steps, wait in line, and return. No commuter would ever do that, because you might miss your train.

It’s obvious that the designer of the Arapaho Center Station had more noble diversions in mind anyway. In the precise center of the thing, there’s one of those giant stone tablets favored by Ten Commandments lovers who like to challenge the Supreme Court, and on it is engraved a truly bizarre screed that seems to have been written by a Buddhist who watches too much PBS:

TO THE PEOPLE THAT USE THIS SPACE

[If I can interrupt here, even before we get started quoting the Tablets of Arapaho, shouldn’t that be the people who use this space? I wouldn’t make such a big deal about it, but the author was working with granite and a chisel.]

Look Around You

Observe the columns—used by the Greeks in the great temples of the Aegean (1200 B.C. to 30 B.C.).

[They look like, uh, big ole concrete columns.]

The barrel vault design of the roof—taken from the Roman arch, the keystone of Roman architecture (700 B.C. to 500 A.D.).

[This is a curved canopy—several of them, in fact.]

The crossed barrel design—common in the great Gothic cathedrals of Europe (1000 A.D. to 1350 A.D.).

[This is two curved canopies, intersecting.]

Gothic architecture also highlighted the magnificence of stained glass seen at the end of each barrel vault.

[Yes indeed, the architect has inserted a little sliver of faux stained glass in roseate hues.]

The forms on the benches represent contemporary thought. Hand carved designs on the bench surfaces and semi-circular stone reliefs (under vault cross point) reflect the primitive style.

[You would have to see this. There are a bunch of grainy Lego blocks and Washington Monument pillars sticking up out of the surface of the bench, so that most of the benches can’t be sat on, and when you do find a crevice to occupy, you’re at risk of being sodomized by a European intellectual’s conceptual brain wave.]

Always look around you and inquire of your environment.

[And watch out where you sit.]

The only boundary to learning is the scope of your vision and curiosity.

[Suddenly I feel like taking some motel management courses at the DeVry Institute.]

This center honors those who have promoted excellence in education in our community.

[What? It’s unsigned? I wanted to enter it in the Katie Awards.]

Meanwhile, I’d rather have a bagel.

Joe Bob DART Decree Numero Three-O:

Elevated stations suck.

Bridges and trestles are good for one thing: sailing over highways so the train can go faster. But elevated stations are a different matter. One thing we know about the past hundred years of mass transit is that elevated anything does the same thing that a 12-lane freeway does. It cuts off neighborhoods, slices apart business districts, and becomes this forbidding barrier that no one wants to cross. That’s why most of the elevated train lines in most cities have long since been knocked down. In places where that was impossible, like Chicago and Brooklyn, the neighborhoods around the elevated tracks became seedy and forbidding. And dark.

In Dallas, they’re just eyesores and a hassle. They also cut off any possibility of commerce growing up around the station. Park Lane, Walnut Hill, Forest Lane, Spring Valley—these places were doomed before they started as far as developing into anything more than park-and-rides. If somebody proves me wrong by building “the next Mockingbird Station,” I still won’t back off my position, because of …

Joe Bob DART Decree Numero Four-O:

There’s a difference between “entertainment districts” and “loft developments” and “multi-use retail complexes” and the stuff at a train station that people actually use.

It’s all well and good to have a Brewmaster Grille and a Scenario Art Gallery and a 10-story office tower that can’t spell the word “Center” clustered around a train station, but those are destinations, not services. The people getting on and off the trains need takeout counters, fast food, and everything found in a 7-Eleven. There are two obvious places where this could happen quickly: at Union Station and at the Monroe Shops building next to the Illinois Avenue Station. Both buildings stand empty. The Union Station gift shop closed up a while back, and most days the shoeshine guy isn’t even there anymore. Monroe Shops had a bookstore and a convenience store, but both are gone now.

Bring the damn rents down! Are we or are we not the capital of capitalism? Open up those two buildings to the free-for-all of competitive small business, and we’ll have everything we need. Wherever there’s cheap space next to a train station, vendors come out of nowhere. It’s a classic entry-level business for first-generation immigrants, who have no problem sitting behind a counter for 18 hours a day, and it inevitably reflects the quirky food and cultural preferences of that area. In Philadelphia there are guys selling hoagies and pretzels. In Lyon women sell pâté and wine. In Denmark it’s herring sandwiches, and in the remoter regions of Russia, grandmothers meet the trains with plastic cartons of beet salad. In other words, you can’t predict exactly what people will sell there. If I were doing it, I’d try fast-food barbecue and tacos. The famous Wingfield’s, home of the finest burger in Dallas (according to this magazine), is just a few blocks from the Monroe Shops. Wingfield’s 2 should be welcome there!

Joe Bob DART Decree Numero Five-O:

Get rid of the cars downtown.

I got the “downtown revitalization” speech from DART. It’s the same downtown revitalization speech I’ve gotten for 30 years. Downtown is worse off today than it was 30 years ago. One Dallas Centre, an I.M. Pei landmark building, is begging for tenants. There’s still that four-block gap-tooth wasteland on Main Street where the heart of the city used to be. The old Hilton stands forlorn and trashed out, with frosted windows and trash under the porte-cochere. Commerce Street, once the center of Dallas nightlife, has no nightlife and, despite its name, has no commerce.

I’m gonna say this one more time: downtown needs less parking. Ever since Jane Jacobs pointed out the principles of urban traffic in the early ’60s, everyone has known that parking spaces destroy downtowns. It’s as true in Dallas as it is in Mexico City or New York or Chicago. That’s why many cities now require new buildings to remove parking spaces, not add them, and give tax rebates for developers who agree to put their parking underground. The more parking you have, the more buildings get torn down. The more parking garages and parking lots you have, the more street life you lose. There’s very little parking in the West End; that’s why it hangs together as a neighborhood. The other thing you can do—London is trying this now—is to make parking so expensive that it’s a deterrent to driving into the center of the city. Cities are even talking about “commuter taxes” for people who insist on using a car downtown, although they usually stop short of an actual tax and just slap a toll on a bridge or tunnel. Of course, this happens naturally if you systematically eliminate parking. Eventually the blocks will start to redevelop, buildings will become more economical than parking lots, and mass transit will thrive.

Instead, the city has consistently done the opposite. When a building goes vacant, it continues to be taxed, creating an incentive for the owner to tear it down for a parking lot, as opposed to, say, redeveloping it as lofts or selling it to someone who specializes in rehab architecture. When a new building goes up, or an old building is redesigned, inevitably we end up with more parking spaces, not fewer. There’s a reason that only a small fraction of DART travel is to downtown. Given a choice between a free DART pass from your company, and having a downtown parking space, most people will opt for the parking space because they haven’t suffered enough yet. There are even three intersections where the DART train actually stops for the cross streets. The train never should stop for cars. Cars always should stop for the train. When you make it tough to drive down there, and tougher to park, and expensive to do either, downtown Dallas will come back like gangbusters and the DART trains will be full. Until then, you’re just encouraging the wrecking ball.

Joe Bob DART Decree Numero Six-O:

Don’t suck up to the master planners.

Consider Galatyn Park Station. Galatyn Park Station was originally supposed to be Campbell Road Station, but the city of Richardson came to DART and said, “Hey, guys, could we move that station stop a little to the north? We think we can get a hotel in there and a corporate headquarters and it’ll all just be groovy.” So instead of building the station where the main drag was and letting it develop naturally, DART let the city co-opt the land so that Renaissance Hotels and Nortel could have a little private park with a DART connection in it. The whole campus looks like a country club golf course, complete with cart paths and manicured lawns. The only sop to the public is the Eisemann Center for the Performing Arts, which, let’s face it, is not going to attract a lot of DART ridership, seeing as most people who use it will be coming from the east or west. It’s a classic master-planning maneuver reminiscent of the days of Mayor Robert Folsom, who never saw a street grid that couldn’t be fenced off, sanitized, and peppered with Houston-style corporate pods.

As DART starts to build out toward the northwest, there will be plenty of opportunities for just this kind of sterile Space Station Chic. One stop at Las Colinas is enough. The bolder move would be to plop down a station right on the roughest part of Harry Hines and let nature take its course. Beware men in suits seeking to “help the city out.”

Joe Bob DART Decree Numero Seven-O:

Put Allen, Frisco, and McKinney on a fast track.

Nobody could have known in 1981, when the first plans were laid down for DART, that we might need a commuter corridor all the way to Sherman, so the communities of the far, far north shouldn’t be held to the same standard as the ones who willfully shot down the sales tax and opted out. DART already lost the chance to build toward Denton, because the Lake Dallas region already has formed its own transit authority and the best we’ll be able to do with that is have Denton commuters transfer between trains somewhere around LBJ. The Red Line is fully built to Parker Road but could go north of McKinney and still get commuters to downtown in under an hour. The delicate politics that would make this possible are essential if the city is to cohere as a city.

Increasingly it seems that DART is taking the shape of the old Interurban Railway, which, as A.C. Greene once pointed out in these pages, never should have been shut down in 1946. Those trains ran to Sherman, to Denton, to Corsicana, and to Cleburne. Waxahachie and Hillsboro aren’t out of the question, either—that would be an even faster commute, due to traffic patterns, than the commute from McKinney.

There’s an easy way to do this: greed. The real estate developers should be all over this. Make ’em pony up.

Joe Bob DART Decree Numero Eight-O:

Dallas is a railroad town.

I have to remind people of this, but Dallas sits at the confluence of more rail than any major city with the possible exception of Chicago. The railroads built the place and they built every place around it. There’s no reason all that right-of-way should go to waste, especially in the coming century of exorbitant gasoline prices and declining airline service. We need to be thinking about connections to other cities—and I don’t mean just the Sunset Limited route, which Amtrak has been talking about rerouting through Meridian, Mississippi, and Dallas and Phoenix for the longest time now. That would be a start, but consider that in Japan, there are 500 trains on the Sanyo line that routinely hit 186 mph. In Europe most city pairs closer than 500 miles are connected by high-speed trains. The future seems to be fewer shuttle jets and more bullet trains. Already, in the United States, Las Vegas mega-developer Steve Wynn is moving forward with a Los Angeles-to-Las Vegas bullet train—three hours from downtown to downtown. The state of New York is doing the same with a train that would run from New York to Buffalo in three hours (current time: nine hours). With state-of-the-art bullet trains getting faster all the time, Dallas to Houston would be 1 hour, 13 minutes. Dallas to San Antonio would be 1 hour, 31 minutes. And Austin and Oklahoma City would be 57 and 59 minutes, respectively.

I would prefer to see this done sooner rather than later. I’m 6-foot-4, and my knees can’t handle much more Southwest Airlines.

Joe Bob DART Decree Numero Nine-O:

Get me to the airport.

I’ve taken the TRE to and from DFW Airport. You need not one, but two buses to shuttle you from the terminal to the station. The first bus takes you to the Super Extreme South So Far Away You’re Beyond The Toll Booths Parking Lot. Then you get another bus that winds around through the American Airlines campus and eventually deposits you at the Centreport station, where your train is rarely synchronized with your previous journey. Originally they were planning to run a spur from Centreport right up into DFW, but that has been scrapped for the time being. In seven years, we’ll have the northwest DART line arriving at the north entrance to DFW. Let’s hope it works better than the one we have now. Everything about getting to and from the airport is expensive and time-consuming. DART is the answer.

Joe Bob DART Decree Numero Ten-O:

Garland is the future.

On the last day of my carefree and carfree week, I get off at the Downtown Garland Station—downtown Garland being such an elusive and mysterious concept to me that I felt like a mystic going in search of sacred caverns. Because all you see from the train at the Downtown Garland Station is an oceanic parking lot (the “Downtown Garland Transit Center”) and some buildings that are too bland to be called nondescript, you have to follow the arrows on the sign and walk two blocks south to the business district proper. Perhaps “business district” is too grandiose a term. Mexican plazas in the remoter parts of Sonora have more activity than downtown Garland at noontime.

I walked past the Central Business Plaza without knowing it was the Central Business Plaza because it was vacant except for a laborer doing some brickwork, had sunken basins full of exposed metal pipe, and seemed to be under construction. Thinking that this was some grand new project for the city, I checked the official plaque: it actually opened in 1975. It was just turned off or something. Surrounding the plaza were a jumble of brick storefronts, several of them empty, as well as the Plaza Theater (WEBB MIDDLE SCHOOL PRESENTS “GREASE”), a photography studio of the weddings-and-graduation variety, a sandwich shop (actually a sandwich “shoppe”), two furniture stores, a quilt shop, an antique store, two bookstores (one Hallmark-style and one secondhand), the offices of the Garland Opry, and farther down the street, a thriving Mexican restaurant and a place called the Cosmopolitan Bistro, which looked neither cosmopolitan nor much like a bistro but was, in any event, closed at lunchtime.

I stayed for a half hour and encountered perhaps four people on the street. At one point an Indiana & Ohio freight train rumbled through—Garland was always a rail hub—but as soon as it was gone, the stillness returned.

And yet, I thought, this is exactly what DART needs: about eight square blocks of blank slate. The existing buildings are charming in their way, and even though the town itself is obscured by the voluminous and forbidding Patty Granville Arts Center—built in that 1960s style of architecture, popularized by Lincoln Center, that houses the arts in some kind of fortress that has to be breached—the scale of the business district is just right for browsing, walking, and dining al fresco. I’m told that the City of Garland has plans to do that very thing, and that they’ve already started having street fairs and other events to soften up the potential tourists. If you can make downtown Garland into a place where people want to party, then there’s hope for anywhere. Get some paint on those buildings. I’ll be the first guy back on the Blue Line to check out the taverns and trattorias. That’s the way it’s supposed to work. Build the station where the old stuff is, and watch it transform on its own. When people from Carrollton start planning train, bus, and bicycle treks into the wilds of Pleasant Grove, we’ll know that DART has arrived.

Joe Bob Briggs is a longtime D contributor. His most recent book is Profoundly Erotic: Sexy Movies That Changed History.