|

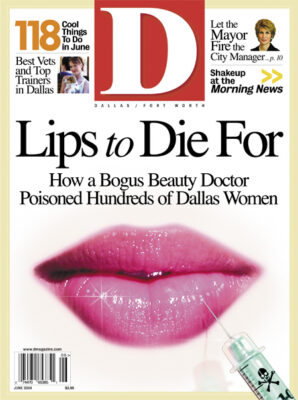

| RETROSPECT: One of Luis Sanchez’s patients said he didn’t even look like a doctor, with his gold chains and diamond stud earring. |

DEE

MYERS—36 YEARS OLD, divorced, blond hair, hazel eyes—was having dinner

with a friend two years ago when she noticed the lips. Her friend’s

lips were fuller than Myers remembered them. Bee-sting full. Pouty,

Angelina Jolie full. Myers’ friend said she’d had them done by a

Miami-based doctor who’d been making regular trips to two Dallas facial

salons for the past six years. Everybody knew about him. Dr. Luis

Sanchez was from Cuba, and he had a supply of a hard-to-find substance

called New-Fill. Myers’ friend explained that New-Fill hadn’t yet been

approved by the Food & Drug Administration, but it had been used in

Europe for two decades. All Myers needed was a referral from her friend

and $300.

Myers admits she’s a “huge fan” of anything that will

make her look younger. She’s had Botox, collagen, and Restylane

injections. Before she married her ex, she told him, “Be prepared. I’m

going to do whatever it takes to stay young.”

After dinner with

her friend, Myers returned home and logged onto the Internet to

research New-Fill. Since coming to Texas from Georgia, she’d worked as

a nurse for two cosmetic surgeons, so Myers knew what to look for. She

learned that New-Fill is a synthetic polylactic hydrogel. It’s

biocompatible, biodegradable, immunologically inert, and, just as her

friend had told her, safely used for 20 years by European orthopedic

and reconstruction surgeons. New-Fill, she discovered, was intended for

the treatment of wrinkles and scars and the augmentation of tissue in

the chin, cheek bones, and lips. Even the plastic surgeon she worked

for said that he’d heard great things about New-Fill, though it had yet

to be approved for use in the United States.

Myers had all the

proof she needed and asked her friend how she could get in to see

Sanchez. Phoning a woman named Jheri McMillian, whose business card

identifies her as a skin practitioner at a spa called Essence of Well

Being, Myers made her appointment—and began spreading the word. She let

a friend in on the secret of Sanchez and his New-Fill injection

treatments. That friend passed the word along to dozens of clients.

Those clients told friends. The drumbeat of Myers and other Sanchez

patients would eventually spread to as far away as Wichita Falls and

Louisiana. One woman, who made an appointment after hearing about the

Miami miracle maker, scheduled a visit for her mother as well.

Myers

remembers the day of her treatment. She arrived at the small upstairs

office in a gray brick building in North Dallas that was “old and

shabby-looking.” In the hallway, several women sat in folding chairs,

their lips covered with a thick, white cream that was used to deaden

the injection sites.

When Myers was told she’d have to pay cash

for her treatment, she rushed to an ATM. “It did seem a little strange,

a little hush-hush, everything but a secret handshake,” she says. “But

I felt it was all related to the fact that New-Fill was not FDA

approved.”

In Sanchez’s mirrored procedure room, a syringe

filled with clear liquid lay on a table. The series of injections and

the gentle massaging of her lips took only a few minutes. She was given

an ice pack to reduce what she was told would be slight and temporary

swelling.

“It was a few days later when I became concerned at

the unevenness of my lips and the fact that they remained more swollen

than I’d expected,” Myers says. When her lips became chapped and

blisters broke out, she tried to contact McMillian to schedule another

appointment.

And the runaround began. Several calls to McMillian

went unreturned. So Myers called Gail Burch, owner of the Laser &

Aesthetic Center, where Sanchez saw patients. Burch told her it would

be some time before the doctor would return to Dallas.

“By

then,” Myers says, “I was getting pretty fed up with the whole mess and

decided I needed to see a doctor who could help me with my problems

immediately.” She again turned to the Internet, typing the words

“New-Fill Dallas” into a search engine one evening, hoping to find a

doctor familiar with the product. Instead, she found a site that

included a diary written by a young Dallas woman.

Recounting a

visit to “a Miami doctor I’d heard about,” the writer described the

same rundown building Myers had gone to, an unnamed doctor whose

physical description sounded familiar, and “hot Dallas women in their

30s and 40s lined up in the hall like they were visiting a back-alley

abortionist.” The diarist told of sitting in the treatment room,

awaiting her injections, and noticing a bottle on a table. The label

indicated it was not New-Fill but, instead, Silicex, “which sounded too

much like silicone to me. … The whole thing suddenly felt wrong.”

The

woman wrote that she had asked the doctor if he was planning to inject

her with silicone, and he’d assured her he wasn’t. Still, she’d become

uneasy and left without receiving her treatment. Once home, she had

looked up Silicex. “It was silicone,” she wrote.

Reading the journal, Myers says she felt she might become ill.

Her

eyes opened, she saw all the warning signs that she’d missed—or

ignored—on the day she’d been injected. There had been, for instance,

the secretive manner in which the doctor had conducted business, the

cash-only demand. Then there was the downscale building where his

treatments were done. She was never asked about her medical history or

required to sign a consent form. And where was the framed medical

diploma that is standard decoration in any doctor’s office?

In

retrospect, even though he had worn scrubs when he’d greeted Myers and

had conversed in all the proper medical jargon, Sanchez hadn’t even

looked like a doctor, with his gold chains, diamond stud earring, and

Caesar-style haircut.

“I was an idiot,” she says. She was

worried about her own health and began contacting women to whom she’d

recommended the doctor. Myers says she felt an overwhelming guilt for

having steered them toward danger. “I went into a three-day

depression,” she says. “All I could think about was if he was injecting

women with silicone and not New-Fill. I wanted him to be stopped.”

|

| TORTURE: Sandy DeVine’s life has become torturous. Her mouth is so sensitive she can no longer eat or drink things that are extremely hot or cold. |

DEE

MYERS WAS NOT THE ONLY SANCHEZ patient beginning to question

the doctor’s legitimacy. Sandy DeVine, a 56-year-old retired nurse, had

also longed for a fuller upper lip and had made three visits to Sanchez

on the recommendation of several friends. Ultimately, she had

decided to have New-Fill injections in her lips and in the lines

that had begun to form around her mouth and eyebrows. Total cost:

$1,400.

“In today’s society,” DeVine says, “women are always

wanting to find ways to look a little better. In my case, I’d always

felt my upper lip was too small. So, when I heard about this doctor, I

locked on the blinders.”

Today, as a result of the injections

she received from Sanchez, DeVine’s life has become torturous. Her

mouth is so sensitive she can no longer eat or drink things that are

extremely hot or cold. If she does have coffee, she sips it through a

straw. For a while, she was embarrassed to drink from a glass in public

because she drooled when doing so. The areas where she was injected

have hardened so much that she has trouble forming certain sounds. Once

outgoing, she rarely smiles these days because of the swelling and

distortion of her lips. Since Sanchez’s treatments, her immune system

has begun to malfunction, and she suffers from oral herpes.

And, she says, “I feel ugly.”

But

while DeVine suffered in silence, Myers turned detective. Despite

growing reservations, she decided to keep a follow-up appointment she’d

made with Sanchez almost three months after her first visit. This time,

however, she went looking for answers.

As Myers entered

Sanchez’s treatment room, she noticed that a large bottle bearing a

New-Fill label sat on a tray beside several filled syringes. “I

immediately knew what the woman had meant when she’d written that

things felt wrong,” she says. “The label on the bottle was old and

soiled, as if it had been Xeroxed and just pasted on. When I told

Sanchez that I would be more comfortable if I could see him draw up the

New-Fill from a new bottle, he dismissed me, saying that he’d already

made preparations for the day. He told me he would promise to draw from

a new bottle the next time I came in. At which point I walked out,

devastated, knowing what I had to do.” Her new role in life would

become that of whistle-blower.

Finding a sympathetic ear,

however, was not easy. The doctor for whom Myers worked made calls to

the American Medical Association and the Texas Attorney General’s

Office but sensed little interest. Myers says when she contacted the

Dallas Police and Sheriff’s Department, she “got the impression that

their attitude was that I got myself into this mess, and they weren’t

interested in getting involved.”

Help, ironically, would finally

come from Sanchez’s home state. Myers saw an MSNBC exposé on the

back-alley beauty business in Florida. Enrique Torres, head of a

Department of Health Unlicensed Activities Office task force, described

myriad scams and illegal procedures being used by the so-called “beauty

doctors.” Back online, she found an article in the McAllen (Texas) Monitor

that quoted Torres. Reporter Bradley Olson had been investigating the

illegal beauty trade across the border in Mexico. Women visiting

back-alley doctors there have been injected with everything from liquid

silicone to mineral oil—even candle wax and paint thinner. But Olson’s

research had also brought him to Torres, who said such illegal

treatments were “prolific, a national problem.” Torres pointed out that

in the last three years, he and his six-man task force had arrested

more than 150 phony doctors in the Miami area alone.

So Myers

telephoned Torres and told him what was happening in Dallas. Torres

guessed that Sanchez didn’t have a license to practice medicine in

Texas, and he acknowledged the possibility that Sanchez was injecting

women with some form of silicone. Myers’ persistence paid off, and

Torres promised he would contact the proper authorities.

Soon, a

full-scale investigation was underway. It would take eight months and a

uniquely cooperative effort on the part of the Austin-based FDA, the

Texas Rangers, the Dallas Police Department, the Dallas County

Sheriff’s Department, and the Dallas County District Attorney’s office.

But bringing Sanchez to justice wouldn’t be easy.

LUIS SANCHEZ’S résumé is a Gordian knot of truths, half-truths,

and outright lies. If you believe what he told Sandy DeVine, the

59-year-old is married with a family. Myers’ first impression of him

was that he was single and likely gay. He says he was born in Cuba,

came to the United States in the early 1960s, served in the Army during

the Vietnam conflict, later earned U.S. citizenship, and is the sole

provider for aging parents who live near him in Miami, which

authorities say is true.

His professional history is more

difficult to verify. He says that after he was discharged from the

service, he attended and graduated from medical school in the Dominican

Republic, then returned to Miami and opened his practice. Later, to an

undercover officer, he said he’d actually gone to med school in Spain.

Yet Sanchez had no records to prove that he was, in fact, licensed to

practice medicine anywhere. His explanation: he’d “run out of money”

and thus had applied for board certification but never fulfilled the

routine residency requirements.

But following a nontraditional

career track did not appear to hurt his business. Sanchez had Dallas

women—and a few men—lined up in the halls, waiting to get his

injections. And investigators familiar with the case say they’d bet a

steak dinner that Dallas wasn’t the only city where Sanchez was plying

his trade. They figure Sanchez treated hundreds of women in Dallas and

perhaps thousands across the country.

Yet making a criminal case

against him proved difficult. When Richard Shing, a sergeant with the

Dallas-based Texas Rangers, took Dee Myers’ statement, his immediate

concern was finding a statute Sanchez could be charged with violating.

“One of the things I quickly learned,” Shing says, “is that the laws

that address this kind of criminal activity aren’t what they need to

be. After becoming convinced of the severe nature of the crime, we felt

the sentencing guidelines offered at the federal level—basically

nothing but a fine—wouldn’t be just punishment for what was done to

these women.”

Finally, with the help of William Brannon, a

special agent with the USFDA in Austin, Shing determined that Sanchez

was in violation of the relatively obscure Texas Occupations Code,

which regulates the licensing of everyone from plumbers and

electricians to doctors. The maximum state penalty, they learned, was

10 years in prison.

So the case was delivered to prosecutor

Bridget Eyler in the District Attorney’s Public Integrity Division.

Soon, she was interviewing a lengthy procession of women who had been

treated by Sanchez. “What he did,” she says today, “was egregious.”

On

a December afternoon in 2002, a sting operation targeting Sanchez was

finally set in motion. A female Dallas Police Department undercover

agent posed as a prospective client and made an appointment for

Sanchez’s next visit to Dallas. When she showed up for her treatment,

she was wearing a hidden microphone. In the parking lot outside, Shing

and Dallas County sheriff’s deputies listened in, armed with arrest

warrants.

Another patient was already prepped with the numbing

cream when the undercover officer arrived and asked if she might watch

the procedure she was scheduled to receive. Sanchez agreed, and the

officer struck up a casual conversation, ultimately asking how long

he’d been in practice and where he was licensed. Sanchez said he’d

practiced medicine for 20 years and was licensed in Florida—but not in

Texas. Hearing that admission, Shing and the other officers made their

move.

“He was very calm about the whole thing,” Shing says.

“What we saw was the kind of charming, disarming demeanor that you

often see from con men. He was playing his game, right up to the time

we took him off to jail.”

It was during the search of the

Aesthetic Center that the investigation took an even darker turn.

Though arresting officers say that Sanchez had seen several other

patients earlier in the day, searches of a biohazard box and other

trash receptacles revealed no discarded needles. Sanchez, they believe,

was re-using needles.

“He wouldn’t admit it, wouldn’t say that he was using contaminated needles,” Shing says. “But it was pretty obvious.”

Sanchez’s

lawyer, Andrew Chatham, refutes the claim. “The woman he was preparing

to inject when he was arrested was the first patient he was to give a

treatment to that day. So it stands to reason there would be no

discarded needles at the time.” Additionally, he points out that among

the items confiscated from the room that afternoon was Sanchez’s

backpack filled with “hundreds” of unused needles.

Whether he

was re-using needles or not, Sanchez’s syringes definitely did not

contain New-Fill. FDA lab tests revealed that he had been injecting

people with an industrial-strength silicone called dimethylsiloxane.

The substance presented a variety of potential health problems, but

none are as frightening as one possibility that emerged during the

investigation. In looking for patients who had been duped by Sanchez,

Eyler interviewed a young man who confided that he had been diagnosed

with HIV prior to receiving his lip injections.

“Normally, in

the process of interviewing witnesses, you do a lot of the work by

phone,” Eyler says. “But because of the nature of the crime and the

possibility that there might have been those who were infected by

contaminated needles, I felt it my responsibility to talk with each

person face to face.” During those interviews, she urged the women to

be immediately tested for HIV.

To date, she says, all tests have

been negative. But the prosecutor admits she wonders how many women,

for whatever reason, might not have acknowledged that they’d received

treatments from Sanchez and remain unaware of the danger they may be

facing.

“One of the things that puzzled all of us,” Shing says,

“was how angry some of the women we contacted got when we tried to

explain what we’d learned. Many were very happy with their results and

told us how wonderful they thought Sanchez was.”

Despite such endorsements, Sanchez pled guilty to the charge of practicing without a license.

ASKED LAST FEBRUARY TO TESTIFY about her experiences during

Sanchez’s sentencing hearing, Sandy DeVine arrived in District Judge

Mark Nancarrow’s courtroom to find it filled with women. Each had been

a patient of the phony doctor. The hard, wooden benches were occupied

by housewives and corporate executives, even a couple of psychiatrists,

ranging in age from early 20s to 60s. “I was stunned,” DeVine says.

Yet

those present, Eyler says, represented only a small percentage of the

victims she’d found during her investigation. Eyler says she became

more personally involved in the case than with any other she’d

prosecuted. “I’ve never had a case that affected so many people,” she

says. “These women were not only lied to and put in danger, but

ultimately made to feel as if they had done something wrong, that

somehow they were to blame for what had happened.”

The daylong

hearing, at which Sanchez was sentenced to five years in prison,

painted a disturbing picture. Dr. James Thornton, a plastic surgeon and

faculty member at UT Southwestern Medical Center, took the witness

stand to explain the dangers to which the women had been exposed. He

reminded the court that the use of silicone for breast implants had

been banned in the United States after it had been shown to spread to

other parts of the body. The liquid form, he said, does the same and is

virtually impossible to remove once injected. It can cause pain,

scarring, and disfigurement.

Eyler says one woman who was

injected by Sanchez has undergone two surgeries in an attempt to remove

the painful knots that formed in her mouth. Another former patient has

irritating, incurable rashes. And there are other women too embarrassed

to confide even to husbands and friends what they had done. Eyler

worries the most, though, that the results of some woman’s next HIV

test might be bad news.

Still, throughout the hearing, Sanchez

repeatedly insisted he was, in fact, a doctor. “Just not a licensed

doctor,” he said. And he testified that his unnamed Brazilian supplier

had assured him he was purchasing New-Fill, never a silicone-based

product, for his patients. Defense attorney Chatham, who advised

Sanchez not to talk with D Magazine, says that his client

feels bad that women have been hurt yet insists that it was never his

intent to harm anyone. “He got conned,” Chatham says. “What

unfortunately happened was that Sanchez was sold counterfeit New-Fill

by his supplier and unintentionally used the silicone product on his

patients.”

Because Sanchez had no previous felony record and his

sentence was less than 10 years, Chatham says he can apply for “shock

probation” for his client. Were it to be granted, Sanchez could soon be

a free man. Meanwhile, there is also talk that he may soon hire an

appellate lawyer to contest the length of his sentence.

For

prosecutor Eyler, then, the fight is not over. She’s prepared to argue

against a motion for any form of probation or sentence reduction. And,

in late April, a Dallas County grand jury indicted Gail Burch and Jheri

McMillian, the women who arranged appointments with Sanchez, for their

roles in promoting and assisting his nonlicensed practice. The crime

they are charged with carries two to 10 years in prison and fines of up

to $10,000.

Burch, who is now listed along with Sanchez in a

civil lawsuit filed by Dallas attorney Donald Schmidt Jr. on Sandy

DeVine’s behalf, did not return calls. McMillian offers a prepared

statement: “I’m deeply saddened and angered at [Sanchez’s]

misrepresentation.” However, she went on to say that Sanchez had

injected her lips and that she was very pleased with the results. “His

work was impeccable, and I have no fear of any untoward effects,” she

says.

Sanchez would be happy to hear it. Preparing to testify

during his sentencing hearing, he looked out into the galley at bench

after bench filled with women who’d come to seek justice for what he’d

done to their faces. They met him with cold, angry stares. Sanchez took

the stand, and, spreading his arms wide in a gesture to demonstrate

bewilderment at his legal difficulties, said, “You’re all beautiful

women. All I see is beautiful women.”

Carlton Stowers is a two-time winner of the Mystery Writers of America’s Edgar Award for the year’s best true-crime book.

Photos: Tadd Myers