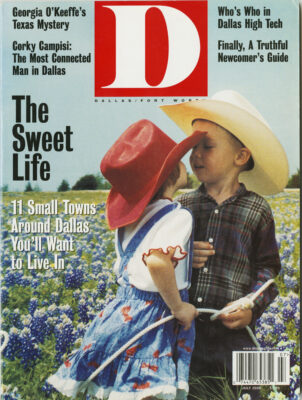

SMALL-TOWN LIFE IS AN AMERICAN DREAM. In small communities folks usually know their neighbors by name, live on

streets named after trees, and walk to a post office on Main Street.

Piano used to be a small town. So did Richardson and Lewisville. But with 100,000 people a year moving into the

Dallas-Fort Worth area, the city has gobbled up these small towns and turned them into suburbs lined with concrete,

strip malls, and starter trees.

So it’s no news that people are fleeing the big city and searching for the peace and quiet of a small town.

This isn’t just a Dallas trend. People all over the United Slates are moving to towns with a history, a friendly

population, and a soda fountain with an empty stool. “People are looking for community.” Says Michael Pawlukiewicz.

director of environmental land use policy at the Urban Land Institute in Washington, D.C. “They want to get up in

the morning, go out tor a cup of coffee, and read the newspaper in a donut shop.”

And with the rapid changes in technology, walking to the corner barber for a haircut is getting easier. Now that

people understand what “telecom-mute” means, they are actually doing it. Hey, a modem works just as well from

Granbury as it does from Uptown.

After weeks of statistical research, interviews, and chatting with the locals, we present the best small towns

within an 80-mile range.

SITTING AT THE COU NTER OF VAN AlSTYNE’s YELLOW Rose Drugstore-where the bags of peanuts are $2; free if you’re

playing dominos-the most exciting thing to watch is the frost developing on the metal pedestal cup holding your ice

cream. Paul Anka’s “Put Your Head On My Shoulder” plays on a jukebox while youngsters sit at kid-sized tables and

chairs, their parents enjoying a Dr Pepper with crushed ice.

Not a bad way to spend an afternoon.

This is the Van Alstyne that Michael Chandler grew up in-where he and his wife plan to raise their family.

“I go into town and still see mostly people 1 know,” says Chandler, whose parents and grandparents are from Van

Alstyne. “But I’m starting to see a whole lot of people I don’t know. It’s amazing how many people are moving into

this town.”

Such a population boom is relative, however. Chandler has a population sign from 1981. when he graduated from high

school. The population then was. ironically. 1,981. Since then, more than 1,000 new folks have decided to call Van

Alstyne home.

Van Alstyne is a town rich in railroad and cotton history. Some of its buildings, constructed in the 1890s, are

still in use. The downtown area includes a bank, post office, city hall, police station, and specialty stores like

the Carriage House Quilt Shoppe.

Chandler wanted to raise his daughters, 9-year-old Shelby and 17-month-old Savannah, with the same small-town val*

ues he grew up with. And his wife, Tracy, didn’t mind moving from one small town, Waxahachie, to an even smaller

one. But they know things won’t slay the same. Experts predict Van Alstyne will be the largest town in Grayson

County within five to eight years.

New developments-Georgetown Village, Steeplechase, Hackberry Heights-have houses that cost as much as $400,000. And

there are plans for a new Braum’s. a major grocery store, a three-story hotel, and a new bank.

YOUR FIRST LOOK AT WAXAHACHIE OFF 1-35 may be misleading. A recent burst of chain activity-the Luby’s, Home Depot.

IHOP, and Applebee’s surrounding the Wal-Mart Supercenter-might mask Waxahachie’s true charm.

But head downtown. You’ll pass Sonic, old neighborhoods with hundreds of Victorian homes, and plenty of

bed-and-breakfasts. Then, you’ll see the square-one of the most magnificent downtown squares in Texas. At center

stage is, of course, the Ellis County Courthouse. Walk around it and you’ll likely hear someone telling the legend

of Harry Hurley, the Italian stone carver brought over in the 1890s to design the elaborate carvings on the Gothic

courthouse.

The story goes something like this: Harry fell in love with his landlady’s daughter, 16-year-old Mabel. He carved

her lovely face into the courthouse for the world to see. And a beautiful face it was. Until her mother and the rest

of the town made life hard for the foreigner. Mabel’s face suddenly became sad. angry, evil. Sweet Mabel turns into

more of a gargoyle as you walk around the courthouse.

Now. let’s learn to pronounce it-walks-uh-hatchie. And what on earth does it mean? It’s Indian for “buffalo

chips,” referring to the buffalo and how they used to-uh-relieve themselves along the local creek banks. Locals will

tell you it means “buffalo creek,” but they’re just being polite.

Carrie Chown answers her phone and finds a customer on the other end. “I have some horse semen for you.” she tells

him.

Although it’s not your typical big-city business call, it isn’t unusual in Pilot Point, Texas.

Chown and her husband, Tom, started the Tom Chown/Willowtree Farm on 12.5 acres near Pilot Point in 1979-when there

were just a few horse ranches and land was cheap. Now, the area is one ranch after another, and land sells for

$15,000 to $25,000 an acre. Their relatively small ranch has about 80 mares and one stallion. Thanks to modern-day

technology, horse ranches can be smaller now because you can FedEx horse semen, lessening the need for the large

spaces necessary when horse owners had to bring their mares to the stallion.

The area draws horse folks from all over the nation, Chown says.

“People can fly into the Dallas area and instead of looking at one horse, they can look at several,” she says. “We

moved here because it’s centrally located. Trends start here. We have a stallion and it’s easier for people to bring

mares to this area. The best of everything (for the horse business) is right here.”

The area’s sandy soil is another reason, helping pastures dry out quickly after a rain so the grass can grow.

There are about 75 horse ranches within a few miles of Pilot Point. The ranches actually stretch from Argyle up 1-35

to Marietta, Okla., with tots of the larger ranches around Lake Ray Roberts.

Horses aren’t the only reason people are moving to Pilot Point, but they are a big draw.

“People are just looking for a little open space,” says resident Jerry Alford. “Everything is migrating north. I

don’t think we’ll be like Frisco, but who knows what’s going to happen 20 years from now?”

Change in Pilot Point is slow, with about 100 new people moving in each year.

“Now, we’re just mostly farms and ranches,” Alford says. “We don’t have any B&Bs, but we do have quite a few antique

stores on the square. And we are doing some things to redevelop the downtown area. There’s a lot of potential here.

It just needs time.”

The signs dir-ecting you to Ennis along the major highways through Ellis County point out what is probably one of

the town’s least attractive sites: the Texas Motorplex, which brings fans from across the nation to Texas for

professional drag races from February through October.

Granted, that’s a unique feature of this Ellis County town. So is the fact that it’s one of only 15 cities with the

Texas Main Street designation. But what really makes Ennis special is its Czech community. One taste of a well-made

kolache and you’ll feel it. too.

The Czech influence is everywhere-from the four Czech social halls to the annual National Polka Festival, where each

Memorial Day weekend you can see locals and visitors participating in everything from the chicken dance to the

klobase-eating contest. Czechs run many of the businesses, including Betty’s Bakery (where you’ll find that

kolache). Ace Hardware, Czech Heritage Shop, H&H Gifts. Quality Inn, and the Ennis Market and Sausage Factory, which

opened 50 years ago.

“It makes for a unique community,” says Patricia Fowler, a lifetime Ennis resident, third-generation Czech, and

president of the Ellis County chapter of the Czech Heritage Society of Texas. When Fowler started school in the

’50s, she didn’t speak English.

The Czechs started coming to Texas in the 1870s. Families would settle and write back to their friends, who might

then join them, eventually forming small communities. Even as recently as the ’80s, Czech was the third most

commonly spoken language in Texas.

The Czech halls sometimes have traditional dances or Czech bands, but more often than not on Saturday nights they

feature live music from a variety of cultures or big, local weddings,

“Everyone’s welcome, even if you’re not of Czech descent,” Fowler says.

“THE COTTON FIELDS ARE TURNING INTO HOUSES.” SAYS LIFETIME resident Linda Cochran about Kaufman.

Cochran has lived in Kaufman for 49 of her 50 years. She briefly moved to another small town near Bryan/College

Station, but it didn’t feel like home. So she moved back. Now she lives on her grandfather’s land just outside

Kaufman and watches as her hometown changes each year.

“Lots of people move from the city, trying to find something here.” she says. “Bui when they get here, they warn to

bring the city with them. They want all the comforts of the city, but they want to live in a small town. Well, if

they wanted that, they should have stayed there.”

Cochran jokes about the big-city folks moving into Kaufman, saying you can easily pick them out of a crowd. But

there is a certain sadness in her voice as she predicts the changes to come.

Kaufman County is 95 percent the size of Dallas County. About 67 percent of the land is composed of woods, farms, or

ranches. And, unlike the flat lands north of Dallas, the countryside to the east pleases the eye with dense foliage

and an actual incline or two.

That land is enticing to developers. And local businesses are having a difficult time-some closing up shop-because

of competition from chains like the Wal-Mart Supercenter and the outlet mall in nearby Terrell.

The town square still has many occupied buildings that were constructed in the late 1800s. Businesses include Scott

Pharmacy and a tea room that operates out of old First National Bank building. Off the square you’ll find the

Kaufman Senior Center, “Home of Recycled Teenagers.”

Many hitchin’ posts (where residents tied up their horses) still remain. These days, cars-about 15,000 a day-pass

through the town square. County commissioners are planning to replace the unfortunate 1950 courthouse in the middle

of the square (a hideous square building encased in beige brick) with a circa-1875 design made of antiquated

limestone block and veneer.

The houses surrounding downtown are mostly lovely little wooden homes, but many larger, Southern plantation-style

houses are nestled here and there. Thirty-five new subdivisions were started in Kaufman County during 1998 and

1999-unprecedented construction for the area.

Another pro for Kaufman: Liquor can be sold, which is a rarity for a small town in Texas.

When Cochran drives through Kaufman, she remembers cruising with her friends from the Dairy Bar to the downtown

square, honking and waving at schoolmates. That doesn’t happen these days. But that small-town atmosphere hangs on.

Cochran hopes it always will.

Like most Texas towns, high school football is a big deal en Gunter. Spend five minutes there and you’ll get to know

the Tigers’ mascot. And energy runs high when the Tigers play their next-door rivals, the Celina Bobcats.

Gunter reeks of school spirit as much as it does of Small Town, Texas. And with good reason. As you drive north on

U.S. 75, past the most congested areas of town, you lake a left at the Van Alstyne exit. Green pastures, curvy

farm-to-market roads, lazy cows, and grazing horses pave your way to one of the best school districts in the Dallas

area. This might seem like hick country, but the kids here are out-performing most of their big-city counterparts.

In fact, the smallest town on our recommended list seems to have the highest respect for the intellect. Gunter has

all the attributes of small-town life: People know their neighbors, love their church socials, and rally around the

high school football team. But they also care deeply about education.

“One of the most important things we have is high expectations,” says Superintendent Rick Cohagan, who has been with

the district for 22 years. 19 of those in his current position. His wife. Cheryl, is the principal at the local

elementary school. Rcsidents give them credit for the excellent school system.

Gunter is one of very few districts in the area to receive an exemplary rating from the Texas Education Agency, the

highest rating the agency has to give. According to TEA’s 1997-98 statistics, Gunter has the area’s highest

percentage of students who passed the TAAS tests-96.2 percent compared to Highland Park’s 95.6-and the lowest

teacher-student ratio at 10.4 students per teacher.

“We’ll add a teacher to the first or second grade before the year starts, even if we are below the state-mandated

ratio,” Cohagan says. “We just think they need a lot of one-on-one.”

Gunter also receives a lot of money per student from the state and taxpayers ($6,807 per student). Gunter students

also get high SAT scores, with an average of 1091, compared to, lor example, the 1087 earned on average by

Richardson ISD.

Gunter used to accept transfer students who were willing to pay tuition for a better education than their own towns’

schools could offer. But the 700-student district (which grew by 100 students last year) recently had to stop taking

transfers to keep up with the town’s growth.

One of the points of pride in this little town is the unusual scholarship program. Students who graduate from Gunter

ISD and have lived in the community for two years receive $?00 a semester for any college or university until they

are a junior, then $750 a semester until they graduate (as long as they keep a 2.4 grade point average).

OK. let’s all practice now: “Go Tigers!” Five years ago, Denison was known only as the birthplace of Dwight

Eisenhower and a convenient gas stop on the way to Lake Texoma.

But thai was before Bill and Maria Tortorici came to town.

The couple had studios in San Diego and Boca Raton and came to Dallas for ArtFest. They loved the Dallas audience

and decided to relocale to a smaller town from which they could commute.

They were shocked when they drove through Denison.

“There was this nine-block stretch of buildings between the Katy Depot and this old, decrepit, really cool structure

(the old Denison High School},” Maria says. “And there was nothing going on. All the Mom & Pop businesses were

attempting to duke it out with the Super Wal-Mart, trying to compete. You can’t do that. So all that had survived

were a few of the mainstay businesses, like the pharmacy and furniture store. Downtown was easily 80 percent

vacant.”

The key was the second floor of all these 125-year-old buildings. Nothing had ever been done with them. If artists

were going to live here, they would have to be able to live upstairs with their studios downstairs. The Tortoricis

talked to city officials who-within three weeks-had Main Street rezoned to allow for residential living on the

second floor.

The Tortoricis bought and renovated one downtown building for their home and Bill’s studio, Tortorici International.

Then they bought as many spaces as they could with plans to later sell them to other artists.

Since that time, 14 artists have opened galleries around the Main Street area.

Gen Grasmuck is one of three senior citizens who came together after the Tortoricis came to town, consolidating

their talents to open the Little Louvre on Main Street.

Grasmuck lived near Lake Texoma but moved to Denison a year ago to be closer to her gallery. Before retiring, she

was a confirmed big-city girl, having lived in Dallas and Houston her whole life. But all that has changed. “1 like

this,” she says. “No traffic. And the people here are so friendly.”

Now, drive down Main Street and you’ll find the Katy Antique Station, Wildwood Art Gallery, and Homestead Winery and

Tasting Room. You’ll still find some typical small-town shops-the pawnshop promoting its saddles and the Robin Hood

Bow Shop–but Denison has become an arts town.

“Artists generally go to areas because they can afford to be there,” Maria Tortorici says. “Then the area gets hip

and trendy and they get priced out. like in Santa Fe. We were cognizant of that and wanted to make sure thai didn’t

happen. We encouraged artists when they relocated to buy their building so that wouldn’t be the case here.”

Four years ago, Maria co-founded Denison Heritage, a nonprofit organization with the mission of turning the old

Denison High School (the first free public school in Texas when it opened in 1913) into a community center. They’re

trying to raise $5 million to convert the space to artist residences and studios, workshops and classes, office

space, and maybe even a culinary institute.

“Everyone on this street is here because they’re meant to be here,” she says. “The energy was just right.”

CORSICANA HAS A BLUE-COLLAR REPUTATION. MAYBE BECAUSE THE town is connected to oil. On June 6, 1894, the first oil

discovered west of the Mississippi was found-by accident-during the drilling of a water well. The town was the

birthplace of the Magnolia Petroleum Company, later Mobil Oil.

From the highway, Corsicana looks like just another of those uninteresting towns that dot the long drive between

Dallas and Houston. Get off the highway, however, and you’ll find quite an interesting community.

Daryl Schleim. executive vice president of the Corsicana Area Chamber of Commerce, is proud that his small town is

one of the most diverse around. According to 1997-98 statistics from the Texas Education Agency, Corsicana’s schools

are 30 percent African-American, 20 percent Hispanic, 49 percent white, and 1 percent other, with 53.5 percent of

the students classified as economically disadvantaged.

Schleim says more Hispanics have moved into Corsicana-actually Texas in general-over the past few years, creating a

makeup that’s more like 38 percent Hispanic and 19 percent African-American

“We have more than 52 countries represented at Navarro.” Schleim says. “We’re attracting all races and all

nationalities who go to school here, then stay in the local workforce after college. I think it gives an advantage

to kids who go to school in a small town. When they travel or move into larger communities, they have already been

exposed to all different cultures. For some kids who grow up in small towns, it’s a shock the first time they leave

that small community.”

Population isn’t the only thing in Corsicana that’s diverse. The town has no zoning, which can make fora weird mix

of buildings. But it also has lovely residential areas of newer homes. And the downtown has been largely preserved.

Corsicana certainly isn’t known for its arts community-but thanks to Navarro College things are happening. The

Historic Palace Theatre was established in 1914 as a dinner theater house and is currently undergoing $700,000 worth

of renovations. When it reopens in the next year or two. it will be an old-style theater with louring plays,

concerts, and auditions for local school programs.

Corsicana also has the Warehouse of Living Arts, which hosts six annual productions and a gallery for art exhibits.

Last year, the Austin Ballet’s production of The Nutcracker came through town. Corsicana also has the largest

planetarium in the south, the Cooks Arts Science & Technology Center, which is part of Navarro.

If you’re a nature-lover. Richland Chambers Reservoir, the third largest lake and one of the prettiest in Texas, is

only 18 miles away, and is only now being discovered by city folks.

But what you really need to know about Corsicana is its sugar content. The town is considering an official Sweet

Tour, including the Collin Street Bakery (famous for its fruitcakes). Navarro Pecan. and the Russell Stover outlet.

Now that’s worth living for.

Sherry and Bob Murray were living in Piano, working for a huge oil company, longing for a different life. Then they

discovered Mineola, with its boarded-up downtown and memories of what the small town used to be.

They bought a grand, turn-of-the-cen-tury Victorian home, sold their home in Piano, and purchased a condo in

Richardson. They planned to commute, working their real jobs during the week and running their new bed-and-breakfast

on the weekends. They soon decided to ditch the condo, commuted for a few years, and now enjoy every day at their

Munzesheimer Manor.

“We thought there was an underlying feeling of resurgence,’ Sherry Murray says. “We formed the first little handful

of merchants. made a brochure, had our first festival, and it’s been extremely successful ever since.”

That was 13 years ago. Now, Mineola is known for its ambience.

The town is home to the Select Theatre, a 75-year-old jewel that is the only remaining movie house in Wood County

offering first-run films on weekends. The Lake Country Playhouse performs live productions 12 weekends a year, and

LaSalle Encounters presents live theater year-round.

Many hotels built during the railroad’s heyday and historic homes surrounding the downtown area are now lovely,

useful parts of the community, transformed into B&Bs, restaurants, and unique shops. Mineola has more than 30

antique stores, lots of specialty and craft shops, as well as art galleries.

Recent renovations to the downtown area include a $600,000 sidewalk project (complete with ADA-approved sidewalks

and rails, as well as 56 hunter green period light posts), a gazebo grandstand, and a sports park. Yes, a sports

park downtown, with a regulation high school basketball court, sand volleyball, and a state-sanctioned horseshoe

pavilion. The town’s old-timers are having a grand time introducing the old sport to the local youngsters.

In May of this year, the Amtrak-Texas Eagle upped its runs from Dallas to Mineola to once a day-an interesting day

trip for those who want to get back to the way things were.

“You can’t believe how many people move out here after staying with us.” Murray says. “We’ve got a circle of friends

who stayed with us first as guests. People are just getting away from the stress, Everything is just moving too

fast. It’s a slower pace out here. It has roots.”

GRANBURY BILLS ITSELF AS THE NORMAN ROCKWALL town on the shores of Lake Granbury. And it’s true.

Each building on the square is maintained in the style of the period it was built. Granbury. land of the I’ B&Bs.

has more than its share of old Victorian homes. I And the quaint Brazos Drive-In is one of the last ! remaining

drive-in theaters.

“The challenge is to maintain the charm,” says Claudia Davis, a transplant from North Dallas. “The other challenge

is to have a downtown that’s not just tor tourism. We want to keep it as a working square. There are cases being

heard at the courthouse, people are shopping, eating lunch, going to the title company,”

Most people who move to small towns assume they’ll still have to travel to Dallas or Fort Worth to keep up with any

type of culture, but not so in Granbury.

Several popular Texas artists live in the area, including Covelle (one of those one-named guys), Art Blevins, and

Robert Summers. The town features art in local galleries, and the Hood County Art Association is currently restoring

the Shanley House for permanent exhibitions.

The Granbury Opera House, which features Broadway shows with professional actors, is on the downtown square. There’s

also Granbury Live, a new theater that features musicals, theater, and Big Band music.

A block off the square is the Tarleton State University Dora Lee Langdon Cultural & Educational Center, which has

done plenty to promote the local arts community since it opened almost four years ago. The center has continuous art

exhibits in one of its buildings– a restored Victorian home-and is booked through February 2001, says Director

Janice Horak.

“A lot of folks moved out here from Dallas and are very supportive of everything that goes on-from the high school

band 10 the arts,” Horak says. “People need the intellectual and cultural stimulation and really look for it

here.”

LADY MAYOR

I ’m a small town’s worst nightmare.

By Andrea Calve

When we came to Texas five years ago, my husband and I wanted to live in a small town. We wanted a place with land

enough for our dogs to romp, shade trees, a quiet place with friendly neighbors, and a big sky. And we wanted to be

part of a community. Then we discovered Lucas.

Nestled against the shores of Lake Lavon 30 miles northeast of Dallas. Lucas boasts more livestock than people. The

closest thing to Starbucks is the bait shop, where the old-timers gather in the morning to drink coffee and grouse

about a town that seems to be going to hell in a hand basket.

And they talk about me: “The meanest bitch in town.” I’m the mayor of Lucas.

When people hear I’m the mayor of a country town in North Texas, they don’t ask why; they ask how.

It is a bit unlikely. I’m the worst nightmare come true for the good ol ’ boys at the bait shop.

I’m a lawyer; I’m from New York; I’m not a Republican: I’m not a churchgoer; I don’t drive a pickup; and I’m

a woman.

How did I become mayor? I volunteered. First, it was for a town committee. That led to an open city council post.

Then, when the mayor moved, my fellow council members tapped me to fill the vacant post. So 1 didn’t have to run. (1

did. however, run for reelection last year. I won easily-unopposed.)

By becoming mayor of a small town, I opened my life to a parade of residents quick to beat a path to my doorstep to

voice their concerns: roads that need fixing, water pressure that needs boosting, taxes that need lowering,

and–above all else- development that needs to be checked.

Therein lies the challenge of being mayor of a small town in North Texas. Aggressive developers have discovered the

charms of Lucas and threaten its country character. A wedge has been driven through the heart of my town.

That’s what being mayor of a community is all about. It’s not a battle of images and abstractions like you find in

big-lime national politics. It’s a real-life struggle over real-life issues with real-life consequences for

real-life people whose names you know and whose cares you share.

It’s a job for the meanest bitch in town.

Get our weekly recap

Brings new meaning to the phrase Sunday Funday. No spam, ever.

Related Articles

Arts & Entertainment

DIFF Documentary City of Hate Reframes JFK’s Assassination Alongside Modern Dallas

Documentarian Quin Mathews revisited the topic in the wake of a number of tragedies that shared North Texas as their center.

By Austin Zook

Business

How Plug and Play in Frisco and McKinney Is Connecting DFW to a Global Innovation Circuit

The global innovation platform headquartered in Silicon Valley has launched accelerator programs in North Texas focused on sports tech, fintech and AI.

Arts & Entertainment

‘The Trouble is You Think You Have Time’: Paul Levatino on Bastards of Soul

A Q&A with the music-industry veteran and first-time feature director about his new documentary and the loss of a friend.

By Zac Crain