It’s a few hours after sunset in m id-March, and-like everyone else at the Hotel krystal bar in Cancun- two Highland Park teenage boys are gearing up to party long into the tropical night. Smoking Marlboro* and sipping beer, the boys sit perehed on bar stools, flirting with a pair of female spring-breakers in their 20s. I lie girls, apparently reliving their college days with a jaunt to Cancun, are surprised these guys are so young. “I can’t believe your parents let you come to ( aucun,1” says one of the women.

One of the Dallas boys orders a second beer, Irving out his high-school Spanish on the Mexican bartender, who smiles and quickly brings a bottle of Corona. The other teen sports a couple of plastic wristbands in different colors-remnants from the previous nights1 revelries.

Last night, they’d invaded La Boom, a disco a few miles down the beach, where a fire-breathing juggler in leopard-striped tights entertained at the entrance. For $20-all-you-ean-drink, they’d done the ’90s version of dirty dancing to rap by the Notorious B.I.G., while bartenders slung drinks two at a time Sometime after I a.m.,a young man, standing at the bar to get yet another drink, leaned over, bowed his head, and threw up on his shoes.

Tonight, when the bus arrives, the teen with the wristbands will add another to his collection, this time from Pat O’Brien’s.

The pair of Highland Park boys insist that, down here, the parents watch the kids like hawks. “The chaperones are assholes,” one boy says. But he confides that their main role is this: If you land in jail, they’ll get you out. “We all have fake IDs,” he says. He doesn’t flash the ID here-and probably not at any bar in Cancun. No need. The drinking age is 18, and no one checks anyway.

Chairs scattered around the lounge fill with teenagers. After spending a hot, sunny day by the pool, they’ve showered and dressed for partying, the guys in baggy shorts, the girls sleek in tight mini-skirts or body-hugging black dresses that show off new tans. They order Coronas and limes, or margaritas and daiquiris.

Makeup perfectly polished, hair professionally highlighted, the girls look as if they’ve stepped out of the pages of Marie Claire, far more sophisticated than the boys. In fact, in this mature social system that long ago sorted out its various couplings, rivalries, and friendships, the sexes don’t seem too interested in each other. Senior boys date younger girls; senior girls date college boys-or no one. Here, they’re all grown-ups.

But how do they afford this trip? At $ 165 a night for a standard double room, the Krystal is a five-star hotel by Mexican standards. For five days and four nights, the kids paid a package rate, about $500-$600 a head, plus another $ 100 for the nightly wristbands.

“Our parents gave us a lot of money,” says one boy, scribbling his name and room number on the bar tab. But, he admits, there was a little anxiety about me trip this year. “We had this big warehouse party. Everybody got busted. It made the national news.”

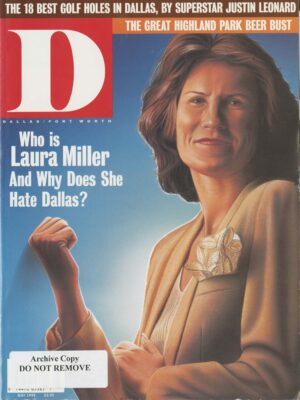

The warehouse party bust put a bit of a pall over the Class of 1999, which has been anticipating its turn at senior revelry for four years. A senior named Anne Tasian organized the party in Deep Ellum for more than 300 students on January 30-complete with buses, wristbands, a deejay, and 12 kegs of beer. Police raided the place, issuing 215 citations for alcohol and curfew violations and sending 18-year-old Tasian to jail overnight.

It looked like the party was over for the Class of ’99. In the resulting fallout, some students were suspended from participating in extracurricular activities. Parent meetings drew crowds. The incident flared briefly in the national spotlight; a producer for A&E flew in to do a story on life in the Park Cities. A task force on underage drinking was formed, headed by U.S. Attorney Paul Coggins, with some of the county’s top law enforcement officials on board.

But has anything really changed? Parents of 10 seniors canceled their plans to send them to Cancun. But most didn’t. This year, 240 Highland Park teens made the trip, accompanied by 20 parents, Some of the students involved in the raid, including Abby Newman, president of the senior class, and Ben Brosseau, vice president and football quarterback, went to Mexico anyway.

In the cocktail lounge, Newman exchanges air kisses with girlfriends. Brosseau, who resigned from the student council in the aftermath, sits down at the bar. Looking a little glum, he orders bottled water and wanders off. Word comes that the bus to Pat O’Brien’s has arrived, and the bar quickly empties. One last night of partying for the Class of ’99 before they return to Dallas and plunge into the home stretch to May graduation.

The 359 seniors had an eventful four years. The class produced 12 National Merit finalists and won two state championships (in wrestling and girls1 cross-country) and dozens of other awards in sports and academic competitions. The young men and women volunteered more than 20,000 service hours. In the fall, they’ll be heading to some of the best universities in the country.

But this is what they’ll be remembered for: The Great Beer Bash and Bust of 1999. And what about party planner extraordinaire Anne Tasian-rumored to have made big bucks on the blowout? She ’11 either change her name-or put the party on her resume. “She should be in the Harvard MBA program,” says one wag. Or chair of the Crystal Charity Ball.

The truth is that though Tasian is a bright, energetic, extremely well-organized teenager, she and the class of ’99 didn’t invent the warehouse party-previous Highland Park seniors have left a virtual blueprint to follow. “In a way, she got credit for something-good and bad-that she didn’t create,” says one mother.

And what about the parents? Sure, this year’s seniors took partying to more brazen levels than ever before. But they did it, in many cases, either with direct help from parents or with the convenient, wilting ignorance of parents too concerned with their childrens’ social status. In a small town that touts itself as a last bastion of “family values,” looking the other way is an art form.

Parents know the essential steps to social success in the Park Cities: attending HP schools, getting into the right college, and joining the right Greek organization. Only by climbing that ladder can they choose the right career and find the right spouse.

The pressure starts in first grade, says one mother, her daughter is a senior at Highland Park High. “Parents want their kids to be accepted so badly they compromise their values,” she says. Thus the phenomenon of sixth-graders carrying $300 Kate Spade purses. Parents won’t say no, not if it means knocking their kids down the ranks of social status. “It’s dog-eat-dog,” the mother says. “The majority are in there to win at all costs.”

Another Highland Park mother agrees. She was shocked to hear little concern about the warehouse party from other parents. “I would have wanted my kids to be at the party,” one mother told her. “That’s where all the cool kids were.”

In an environment where so many parents are high achievers, it’s hard for some students to find a way to stand out while competing with the children of the best and brightest. “My daughter was a positive leader in other schools,” says one mother. “Here, she had to fight to get to the top of something. And the girls are so bitchy.”

Stories of competitive teenage social climbing make it sound as if living in the Park Cities is a version of Lord of the Flies, costumed by Ralph Lauren and fueled by booze and money. From Dallas to the ski slopes to Cancun and back again, the party never ends, and efforts by law enforcement to stop it are deemed laughable.

Finally, this spring the cops decided to try to beat the kids at their own game.

Alitlle after 7 p.m. on the last Saturday in January, Doyle and Mike, two undercover cops with the Dallas vice squad, drove their Trans Am with dark tinted windows through the parking lot at Highland Park High School. Parents were dropping teens off for the Hi-Lites girl-ask-boy alcohol-free dance. These kids aren’t old enough to have cars, the officers thought. This can’t be the meeting place.

For the next few hours, Doyle and Mike cruised the Park Cities, talking on the radio to Highland Park and University Park officers sitting in unmarked cars along Northwest Highway. Mike is 37, Doyle in his mid-40s. Each with more than 10 years of experience in vice, they must have felt a bit absurd-grown men, used to busting criminals, on the trail of teenage party animals.

The bust really started on Wednesday, when University Park Police Chief Bob Dixon got a call from a mother who said her daughter had told her about a big warehouse party scheduled for that weekend after the Hi-Lites Dance. Students were talking about it openly at school. Kids who paid the sliding-scale fee would get a wristband, a bus ride to a downtown warehouse, and all the beer they could drink. Just like spring break in Cancun.

But the concerned mother didn’t know the location; even the kids didn’t. They were supposed to find out where to meet at the last minute. Promising to call back, the mother hung up.

Dixon contacted HP Chief Darrell Fant; both knew the party would probably be somewhere in Dallas, outside their jurisdictions. In 1991, police had cited 23 students after a freshman girl \ party spun out of control and drunken teens trashed the family home. Over the next six or seven years, as officers in the Park Cities tried to ênrorc^^er^nemiic^onc^oniom^arties^arit watched as students moved the events to ranches and to the inner city, where empty warehouses could be rented for a night. In 1993, about 200 students took buses to a ranch in Kaufman County. After a false 911 call reporting a shooting, Kaufman sheriff’s deputies raided the party and found a “pickup-bed-full” of beer and hard liquor. They arrested 96 Highland Park students for underage drinking.

The reaction of parents, including Dallas Morning News publisher Burl Osborne, was to file a lawsuit against the authorities for violating their darlings’ “civil rights,” demanding $50,000 in damages per child. (The lawsuit was settled out of court, with the sheriff’s department agreeing to pay the parents’ legal fees and change some of their procedures.)

Underage drinking isn’t a problem peculiar to the Park Cities. Teens everywhere throw warehouse parties. But with Highland Park students in charge, the warehouse events have grown bigger, more sophisticated, and more frequent-as if the high schoolers were taking notes from older siblings in college fraternities and sororities. Attendance at the school-sanctioned parties dropped off, and the “after” parties became the real events. “Kids have the attitude that it must be all right,” says one female junior, “otherwise parents would be more concerned, more vigilant.” You’d think so: At least 15 HPHS students have died in alcohol-related accidents in the past 10 years.

Keith Hester, now a member of the Corps of Cadets at Texas A&M University, had moved from a Richardson school to Highland Park High after his sophomore year. He was amazed–in the Park Cities every weekend night and some weekdays, some student threw a party at his or her house. When police or parents broke up one bash, the teens moved on to the next, then the next.

Often, no one received a minor in possession ticket. Many students nan when police showed up or, if cornered, gave fake names. One exception: Last June, a group of students climbed the fence into the backyard of a house in the 3300 block of Colgate; the family was out of town. After the teens got drunk and threw the lawn furniture in the pool, a neighbor called police, who arrested 23 students. Chief Dixon invited the parents of the students who received citations for underage drinking to meet with him: only five or six parents showed up.

Throughout his senior year, Hester says, the parties escalated. Every senior is expected to give at least one party during the year, usually at home. In addition, the senior class had six or seven large bashes-two warehouse parties, and several others at ranches owned by families of senior boys. Country-pop singer Pat Greene played at one ranch party.

The senior girls always organized the parties, as their mothers organize fancy charity balls. In 1998, one friend of Hester’s-a pretty, popular girl who belonged to the Highland Belles drill team-took on the responsibility. The formula was always the same: hire DART buses, buy wristbands (or once, glow-in-the-dark necklaces), hire a deejay, rent the warehouse. The step-by-step procedure is “written down and handed from class to class,” says one mother.

Hester occasionally helped, stationed at the door of the bus to check that everyone who boarded wore a wristband, Getting the alcohol was easy. Older siblings made the actual purchase. “The only difficult thing was raising money quickly enough to put the money down for the buses and warehouses,” Hester says. “We did all the business at school-pass out bracelets, collect money, The kegs you can get the day of the party.”

The meeting site changed every time. The parking lots at Moody Coliseum and Northwest Bible Church were popular for a while. “The site was the last thing everybody found out,” Hester says. “Usually on that Friday at school, [my friend would] tell people, and word would spread like wildfire.”

The drinking started in the parking lot before the bus arrived. “You worry about the police when you see them driving around the corner,” Hester says. “Even if you have beer in the car, there’s not much they can do unless you flash it in their face. The kids know this.”

For as long as most Highland Park students can remember, they have been largely untouchable, by the police and, more importantly, by their parents. There was no reason, before Jan. 30, to think that would change. When Dixon go( the tip in January about the Anne Tasian-orga-nized party, he and Fant decided to respond aggressively. They called Dallas Chief Ben Click and told him they thought their kids were heading his way to party, either to Deep Ellum or the Industrial Boulevard area, Click agreed to provide manpower to handle 300 to 400 potentially intoxicated teens.

Dixon put two detectives on the case, and Fant assigned detective Walt Mabrey and a young female officer from his squad to take part. Lt. John Dagen, head of Dallas vice, assigned a handful of officers to the stakeout and sent others to scout possible locations. A sergeant from the Texas Alcoholic Beverage Commission joined me team. But as of early Saturday night, Dagen and his officers hadn’t found a warehouse that appeared a likely site.

Then, a little before 9 p.m., as six or seven unmarked vehicles roamed the Park Cities, the undercover mother called a detective. She’d secretly followed her daughter’s car and had discovered the rendezvous point. The officers scrambled to get there before the buses arrived.

In the HPHS gym, couples danced to the Clash and the Sex Pistols as the ’ 80s punk rock-themed Hi-Lites dance lurched toward its climax, the crowning of the King and Queen. The evening had been organized-and paid for-by the girls. First, everyone went to someone’s house, where mothers snapped photos. Girls took their dates to dinner, then paid $15 each for tickets to me dance. But attendance was sparse. By 10 p.m., everyone was thinking about the next event-most freshmen heading to home parties for “dessert,” the upperclass-men to the big bash.

In Deep Ellum, Anne Tasian’s party was about to start.

Wristbands already had been purchased and distributed during and after school. On Thursday. Jan. 28, Tasian had filled out forms reserving two DART buses for a shuttle on Saturday night. She paid $575, requesting that the buses arrive at Shearith Israel, 9401 Douglas, at 10 p.m. and be available for 5 hours, until 2 a.m.

Tasian, the daughter of Dr. Berge and Diane Tasian, lives in a corner-lot house in University Park, nice but modest by Park Cities standards. Described as likeable, energetic, and open, Tasian had inherited a system of party planning from previous classes. From the beginning of her freshman year she’d made a name and a social niche for herself as “The Organizer,” which made her a vital pan of the school’s inner circle of popular kids.

Early on Saturday, Tasian’s plan hit a couple of snags. First, the man she had talked to about working the door backed out. so he called his brother, Richard Black. Black, a muscular 34-year-old African-American, agreed to take the job.

Then Tasian ran into another problem: the booze. That afternoon, she visited a friend who worked in a retail store at the mall. Eric Sebastian, an employee at the store, refuses to say which store or even which mall. Crying, Tasian told her friend she had the party arranged for that night, but she was soooo busy, she couldn’t get to Deep Ellum to set up the kegs.

Sebastian, 25, didn’t know Tasian, but he sympathized. “She got in a bind,” says Sebastian. To him, it seemed like no big deal. “They’ve had the same party every weekend this year.” The Richardson resident was going to Deep Ellum for dinner that night anyway. “Friends [bought alcohol] for me in high school,” says Sebastian. “I’ve been to thousands of parties like that. They were being responsible. She said they had buses.”

Sebastian had agreed to a non-adjudicated finding of guilt after being charged with marijuana possession in August 1998 and received 12 months probation. A violation of the terms of his probation could send him to jail, and one probation violation warrant had been filed in December already. But Sebastian wanted to help Tasian, and he rebuffed her offer to pay him.

About 6:15, Sebastian met Tasian, who was dressed for a dinner date, at the warehouse. She unlocked the back garage door and, saying she was late for dinner and a social function, left in a hurry.

Sebastian walked across the alley into the Spirits liquor store at 2825 Canton. He peeled off nearly $1,500 in cash for 12 kegs. At 15.5 gallons per keg, that was enough beer for 300 teenagers to drink at least six beers each. Employees of Spirits rolled the kegs across the alley into the warehouse that fronted on Commerce Street

Owned by Dallas parking lot magnate Don Blanton, the grimy 50-by-125-foot warehouse had most recently served as a paint-and-body shop; inside, it offered little more than a concrete floor and two bathroom stalls. In 1996, Dallas police had sent Blanton a letter telling him to cease leasing another warehouse he owned for such parties. But sometime in January, Tasian had signed a contract to rent the warehouse at 2816 Commerce.

As bands started taking their stages at clubs in Deep Ellum, it was almost time for Tasian’s big event to gel underway. A deejay with a sound system would soon arrive. The clerks set the kegs up along one wall, tapped them, and Sebastian, not even pulling a cup for himself, hit the road.

At 9:45, the parking lot at Congregation Shearith Israel was crowded with the cars of those attending the bat mitzvah of a Hockaday student-and at least four unmarked vehicles carrying undercover police officers. Doyle and Mike watched from the Trans Am as students weaved their cars in and out of the lot. A few parked and got out, heading to the bushes behind the synagogue to urinate.

About 10, as the crowd from the bat mitzvah was leaving, two DART buses drove up and suddenly teenagers, all wearing wristbands, began to appear, tumbling out of cars and trooping to the buses. Some were drinking from cups, but the officers saw no beer cans.

As soon as the buses filled, the drivers pulled out. telling those left behind they’d come back for a second load. Doyle eased the car onto Central Expressway, joining a caravan behind the buses of 10 to 15 cars filled with students. Guys in one car noticed them and angrily began gesturing, like whatchoo-lookin-at?The officers ignored them.

The buses pulled into an alley behind the empty warehouse on Commerce. The streets were teeming with people, mostly college students and couples in their 20s heading to clubs. Doyle parked the car down the street and walked toward the warehouse, where teens from die car caravan were waiting to enter the warehouse. One party-goer from the caravan confronted the undercover officer on the sidewalk.

“Why were y’all following us?” the suspicious student demanded.

“I don’t know what you’re talking about,” Doyle said and walked away. At that moment, the front door to the warehouse was opened by doorman Richard Black; the buses emptied and kids, including the wary teen, began streaming inside as Black checked their wristbands. As soon as the buses emptied, the drivers left for another load.

As the teenagers disappeared inside, Doyle and Mike moved their car closer to the front door. Mabrey was a block away, parked under an overpass. At least a dozen officers were watching the front door of the warehouse-waiting for “probable cause.” The sergeant with TABC had warned them not to enter until they had evidence a crime was being committed, i.e., someone under 21 was drinking alcohol. They didn”t want lawyers screaming about civil liberties violations.

So they waited. The buses returned A few teens in their own cars straggled in late, wandering next door to Stromboli Joe’s to ask where the party was. By midnight, officers estimated that about 300 students were inside. Periodically, kids emerged with cell phones, made their calls, and went back inside. One caller brought his cup of beer out with him, then thought better of it: he went back inside, put his cup down, then came back out to dial.

Suddenly, just after midnight, the door opened and three or four guys emerged, carrying another boy. obviously extremely drunk, by the shoulders. A teenage girl with dark hair, dressed in black, followed. “Get him back in here-don’t let anybody see him,” she scolded. The boys dragged their sick friend back inside.

Doyle and Mike got on the phone to Lt. Dagen and told him they’d seen the teenager with what looked like beer and another kid who looked very sick. Dagen ruled they had probable cause and gave the signal. At about 12:30 a.m., two dozen police officers, some in uniforms, some in plainclothes, converged on the front door. “Police officers!’1 Mike shouted. “Open up.” A^^ mail slot in the front door popped open, and a pair of horrified eyes peered out. A few minutes later, someone inside opened the door. The first Big Beer Bash of 1999 was busted.

Carefully dressed in black for her night in the spotlight, a sullen Anne Tasian sat on the filthy concrete floor of the warehouse, hands cuffed behind her. Tasian’s earlier bravado was gone, and she seemed on the verge of tears. An older woman approached Mike and demanded that he take the cuffs off. “She’s being released,” the woman insisted.

“No, this girl’s going to jail,” Mike said. “Are you her mother?”

The woman shook her head no- “I’m just a friend,” she said. “The only one I’m talking to is her mother,” the officer said. When Tasian realized she was going to Lew Sterrett, she started crying.

“Why are they taking me?” Tasian sobbed. Clearly, she’d never conceived that throwing a beer party could land her in jail.

As police rushed in through the front door, teenagers had skittered to the opposite wall, cups of beer flying to the floor as they went. When Mike entered, the first thing he saw was the sick teenager on the nasty floor, heaving his guts out. “I remember seeing blood in his vomit,” Mike says. “There’s something wrong when you’re puking blood.” Police called an ambulance; paramedics quickly arrived and took the sick teenager to Baylor for treatment of acute alcohol poisoning.

“Who’s in charge?” Mike yelled over the music. The teens just stared. Mike confronted the deejay and told him to turn off the tune.

“Buddy, it looks like you and the doorman are the only adults here,” the officer said. “Oh man, I’m just putting on the music,” said the deejay. He scanned the crowd, then pointed out the girl who hired him: Anne Tasian, the perky brunette. Mike recognized her as the one he’d seen at the front door, telling the boys to bring their sick friend back in. They’d simply dumped him on the floor. No one had called for help.

“Are you in charge of this party?” asked Mike.

“Yes,” Tasian nodded. “I’m the one who put it on.”

“Okay, who else put the party on with you?” he asked.

“Nobody, just me,” she said.

Mike informed her that she was under arrest for furnishing alcohol to minors. He snapped handcuffs on her and sat her by the front door. At first, she didn ’t seem too concerned. Handcuffed and seated next to her, the doorman seemed more upset. But later, one detective says, a defiant Tasian started yelling at police. “What are you doing here? This is a private party.”

It took police three hours to process all the partygoers, who ranged from age 14 to 19. If the teens insisted they had nothing to drink, officers asked them to blow into portable breathalyzers. Those who’d been drinking received citations for underage consumption or possession of alcohol. For those 16 and under, police wrote tickets for violating the midnight curfew and called their parents. Officers were surprised that few teens seemed concerned about getting in trouble with their parents. Some used their cell phones to call home; a few called their attorneys. Most, their beer buzz long evaporated, were simply irritated the process was taking so long.

Parents, including some prominent residents like Tom Hicks, who had two sons inside, began appearing on the sidewalk outside. Mike and Doyle started escorting parents inside to find their kids.

Tasian’s parents were subdued. “They weren’t angry,” Mike says. “They were concerned about getting her out.” (Tasian, her parents, and her attorney, David Judd, did not return phone calls for this story.) About 3 a.m., two patrol officers took the senior to the county jail. Booked into a holding tank with two commodes and four telephones, the 18-year-old spent the next five hours with 15 to 20 women arrested for public intoxication and prostitution. On a Saturday night, it was probably standing room only.

While waiting for Tasian to be fingerprinted and photographed, Doyle talked to her about the enterprise. She looked tired, her eyes red from crying. And she was mad. Leaning against the wall, Tasian griped that the party was organized by a group of girls, but she was getting all the blame. Her name ended up on the warehouse contract. She was in charge of getting the kegs, She’d arranged the deal for the DART buses. Tasian told Doyle that at first the girls thought they had made a profit, but when all was said and done, they probably netted only $300.

The teenager complained about the students in the car caravan. Tasian told Doyle she’d budgeted several hundred dollars to call cabs for those too drunk to drive home from the synagogue parking lot. The whole idea behind the buses was that nobody would drink and drive. And to top it all off, she was the only one of her friends to be arrested.

“I’m going to spend the night in jail, and they’re home asleep,” she moaned. Doyle commiserated, telling Tasian her friends were probably facing their parents, getting in a whole lot of trouble.

“No, they’re home asleep,” Tasian insisted.

Though she complained, Tasian seemed resigned. The school might give her in-house suspension, but hey. she was about to graduate. Doyle got the impression it was no big deal. At about 10 that morning, Tasian’s mother posted a $500 cash bond and took her daughter home.

The American Airlines flight back to Dallas from Cancun was subdued; glassy-eyed teenagers slept or read while moms-trim, carefully dressed versions of their pretty daughters-chatted. “Where’s the party tonight?’”quipped one mom as the plane touched down. “Who’s going to provide the margaritas?” The rolling party had landed.

Back in Dallas, calls to parents whose children participated in the warehouse party are met with groans. Many have hired lawyers, concerned that the citations will stain their daughters’ and sons’ records just as they head into sorority and fraternity rush season at college. Many of the M1P charges are set for court in August.

The senior class, represented by president Abby Newman, has led the way in making amends–urging seniors to come together to do community service, making presentations to middle-schoolers about the consequences of making poor choices. Everyone is saying and doing the right things to show remorse.

High school principal Bob Albano believes the school has turned a comer. “In the long haul, the kids have done a wonderful job with this,” he says. “I compliment them on their courage and their leadership. They chose to step up, and I admire that.”

But as May begins, the Class of 1999 is sliding headlong into its heaviest party season. The annual Powder Puff game, in which Highland Park students take over a Dallas city park to watch the girls play football, is traditionally accompanied by lots of booze on the field, brawling females, and an after-hours party. And then comes Senior Prom, for which limos and hotel rooms for post-prom parties have been rented, often with the help of parents. And many seniors, even some of those ticketed at the warehouse, will be drinking.

HPISD Superintendent John Connolly says he’s encouraged by the positive response of the parents to the high school’s discipline. His calls from parents were running eight to one in support of the school taking a stand. Connolly ’ looks thoughtful when asked about the coming party season. It’s clear he doesn’t want to think that the drinking will ’ continue as before.

But Bob Albano knows the drinking will continue. “The reality is, ^when a school takes a stand like this, it goes underground,” Albano says. “Trie hotel parties are going to continue, for the seniors are no longer going to have an association with the school.” As for parties involving underclassmen, he pledges that, if citations are brought to the school’s attention, they’ll investigate and “issue consequences.” This summer, a group of administrators, parents, and students will develop a “leadership honor code” to address the problem.

But the truth is, nothing will really change until parents demand it. The social structure here isn’t going away, and most people don’t want it to. As long as the coolest, richest kids continue to throw beer parties, the students will want to be mere.

The few parents who do put their feet down feel isolated. One mother says that at first, she’d call other parents when she heard about a booze party. “One person told me that he had their keys, so it was safe,” says one mother, who tried unsuccessfully to forbid her senior from attending the Deep Ellum party.

“When I moved here, I was shocked at what goes on,” she says. “You get numb to it. I feel like now it’s flaunted in my face. I’ve kind of tucked my feathers in and accepted it.”

In the kids-will-be-kids world of Highland Park, popularity is priceless.

ECONOMICS OF A WAREHOUSE PARTY

Teenage keg parties don just happen. They lake organizational planning, skill, and attention to detail.

After basting the high-protile Deep Ellum party, police estimated that organizer Anne Tasian, a senior at Highland Park High School, may have pocketed anywhere from $1.500 to $4.000. (She told an ofticer the profit was only $300.) A look at the finances of a teen beer bash: EXPENSES:

4(H) Wristbands: .$100 @ 25 cents each (shown at right)

Two DART buses from 10 p.m. to 2

a.m.: $575

Warehouse: About $ 1.000

12 Kegs of Beer. $1,473.11 (with a $486 refundable deposit)

Deejay: $200 h. Doorman: $150

Total Expenses: $3,298.11

REVENUE:

In an impressive show of marketing savvy, tickets tor the Deep Ellum bash were sold on a sliding scale: Seniors paid $35 per couple: juniors paid $40; sophomores paid $50; and freshmen paid $55.

Assuming .1(H) tickets sold at an average of $40 per couple: Total Revenues $6,000 PROFIT; $2,701.89

Get our weekly recap

Brings new meaning to the phrase Sunday Funday. No spam, ever.

Related Articles

Arts & Entertainment

DIFF Documentary City of Hate Reframes JFK’s Assassination Alongside Modern Dallas

Documentarian Quin Mathews revisited the topic in the wake of a number of tragedies that shared North Texas as their center.

By Austin Zook

Business

How Plug and Play in Frisco and McKinney Is Connecting DFW to a Global Innovation Circuit

The global innovation platform headquartered in Silicon Valley has launched accelerator programs in North Texas focused on sports tech, fintech and AI.

Arts & Entertainment

‘The Trouble is You Think You Have Time’: Paul Levatino on Bastards of Soul

A Q&A with the music-industry veteran and first-time feature director about his new documentary and the loss of a friend.

By Zac Crain