ELEVEN YEARS HAD PASSED SINCE I LAST SAW TOMMY. A chubby tough kid with bushy eyebrows and a grown-out crewcut, he taught me what being a sixth-grader was all about. I remember throwing rocks down by the creek with him, and riding motorcycles, and lighting off smoke bombs. Tommy (not his real name) was a religious boy, strong enough in his Catholic faith that he wore a brown scapular to school, ignoring the sometimes vicious playground taunts. His family was so devout they had a vial of holy water in each room of the house. One of the bonds we shared was that we were both Catholic, both parishioners at All Saints.

I wanted to get in touch with him after all this time because I was certain he would know something about the incidents at our church. As it turned out, he knew a lot more than I ever believed possible. Some of it he could tell me, but some he could not due to pending litigation. All Saints-where my sister got married and where I gave my first confession and where my parents still attend weekly Mass- is in the middle of an explosive predicament for the entire Catholic Church that has left the Diocese of Dallas trying to smother a live grenade.

Like most other local Catholics, I first learned from the newspaper that some of our priests had been accused of molesting children. Tommy, however, knew firsthand some of the secrets that had been kept from the parishioners at the Far North Dallas church. He was sexually abused in the early 1980s, fondled by the now infamous Father Rudy Kos. It happened in the All Saints rectory, where Kos at one time lived with Robert Peebles and William Hughes, the two other priests facing allegations. There are four John Does in the case against Peebles and a Jane Doe against Hughes, who stands accused of repeatedly molesting one 13-year-old girl. Ten John Does have sued Kos. The priests have admitted to many of the charges while denying others, and all are facing criminal investigation. Whether or not the abuse occurred is not a point of legal contention. What’s at issue is who else in the Church hierarchy is responsible.

Hundreds of priests across the country have faced similar allegations, but the Dallas cases are unique because the plaintiffs have added national organizations to the list of defendants, claiming that institutional negligence extends to not only the local bishop but also the United States Catholic Conference and the National Conference of Catholic Bishops. Plaintiffs attorneys claim these ecclesiastic entities have known of rampant sex abuse among priests for years prior to the incidents in Dallas, but conspired to help bishops cover it up in an effort to avoid scandal, which has in turn allowed offending priests to continue their victimization. The Church says the cover-up charges are unfounded, that the effort to extend blame upward in the hierarchy has been trumped up by greedy plaintiffs attorneys.

Child-molesting priests have been the American Church’s crown of thorns for more than 15 years. According to Father Tom Doyle, a priest and Canon lawyer who has studied the issue extensively, the Church has paid more than S650 million to settle cases, quietly whenever possible. Damages being sought in Dallas are presently unspecified, but the total will likely exceed $150 million. If the Dallas district court jury sides with the plaintiffs, agreeing that responsibility lies high up in the hierarchy, it could establish a legal precedent with the potential to cripple the Church nationwide.

Currently the Dallas cases are held up in the discovery process, as the courts decide which Church documents are and are not protected by the First Amendment. Attorneys on both sides say they hope to go to trial early next year. The defense, supported by the largest and oldest institution in the world, is eager to remove the stench of scandal and must make its case on two levels: From a diocese standpoint, the Church is trying to distance itself from the offending priests. Nationally, the Church is trying to distance itself from the diocese.

Meanwhile, plaintiffs attorneys Sylvia Demarest and Windle Turley, two salty, aggressive personal injury lawyers, are trying to cement those uncertain links by establishing that the Dallas diocese acted in conjunction with a national plan of covering up abuse.

For years, when allegations surfaced, priests in Dallas and around the country were simply sent for psychological treatment and then re-assigned to another parish. But Bishop Charles Grahmann claims that he and his predecessor, Thomas Tschoepe ( 1969-1990), followed that course only because they lacked full knowledge of how deep the problem went and were often misled by psychiatrists who had yet to come to grips with the scope of pedophilia. “Being trusting doesn’t mean you’re negligent,” says diocese attorney Randal Mathis, who has a reputation for handlingformidable cases. “Bishop Tschoepe only knew the information given to him. Without being informed of much, there was nothing cumulative for him to understand.”

But in the case of Father Rudy Kos, the plaintiffs will argue, the diocese was aware of his abusive potential even before he became a priest. In 1975, as Kos was applying to seminary, the Dallas diocese contacted his ex-wife, seeking an annulment of his former marriage. Platonic friends since childhood, the two married after Kos proposed in a letter. The couple lived on an Air Force base for five years in an unhappy, unconsurnmated marriage before the woman kicked Kos out of the house upon discovering a trunkload of love letters from several young boys he met abroad. During her interview with the seminary official, Kos’ ex-wife said specifically that Kos should not become a priest because he was sexually attracted to boys. “She implies that the petitioner has some problems,” read the report. “She says that the service chaplain knows about the problem. Something is fishy.” The interviewer made a special note to investigate further, but the ex-wife was never contacted again.

The Church granted the annulment and accepted Kos into the seminary-the first of many times it would give him the benefit of the doubt. Throughout his tenure as a priest, he surrounded himself with boys; observers note that he was very protective of them- and very physical with them. His behavior may have seemed odd, but without any concrete evidence to verify what no one wanted to believe, Church personnel were hesitant to intervene.

In 1985, Kos left All Saints for his new assignment at St. Luke’s in Irving. Almost immediately, fellow priests there grew concerned about his behavior. One kept journal entries of Kos’ activities and sent them to his superior, along with a copy to Monsignor Robert Rehkemper, the vicar general of the diocese and essentially the bishop’s vice president. In July of 1986, the priest sent a letter directly to Kos, and forwarded a copy to Rehkemper and Tschoepe. “I find the boys and young men who stay overnight with you in your room incompatible with the way I want to live in this rectory,” he wrote. “I am asking that this come to an end.” The slumber parties stopped, but only for a matter of weeks.

Then in 1988, Tschoepe, with input from Rehkemper, assigned Kos to be pastor at St. John’s in Ennis, leaving him in charge not only of the church but also of its school. Kos’ only supervisor was miles away in Dallas, and again, the other priests at the parish began registering complaints about him. Occasionally he was sent for psychological evaluation. In April 1991, his therapist said Kos sounded “like a classic, textbook pedophile,” and recommended immediate removal from all contact with boys. But Kos convinced Rehkemper that treatment had changed him, and he was allowed to stay at St. John’s,

This time, Kos’ behavior was documented by assistant pastor Father Robert Williams, who sent a 12-page letter to Bishop Grahmann chronicling Kos’ actions. The bothersome events began on Williams’ first day at the parish. “We went in the back door to his two rooms, and he told me the old assistant never came back there. It seemed to me a strong hint,” he wrote. The hint became more disturbing as Williams noticed boys sleeping over at the rectory almost every night. He pointed out that Kos’ only adult friends were two men in their 20s who used to be altar boys at All Saints. Williams never believed Kos’ relationships were innocent. “He constantly said that he liked to work with boys, but all the work was happening in his bedroom or study. He did not work with youth groups at the parish. He never worked with boys in a public way.” However, many times he did see Kos rolling around on his bed, wrestling or tickling the boys. And often he gave them “prolonged frontal hugs” which seemed to make the boys uncomfortable. He held them, Williams wrote, “almost like they were a towel with which he was drying himself.”

One question bound to figure in the upcoming trials is this: What in fact did Church officials know about pedophilia and when did they know it? In its defense, the Church reiterates what psychiatrists say, that an understanding of pedophilia and ephebophilia (the medical term for attraction to post-pubescent children) has only recently come to light. Until recently, sexual disorders were seen as moral weaknesses, not medical illnesses, they say, and offenders were treated as sinners, not criminals, Reassignment was acceptable, the defense contends, because the recidivist nature of child sex abusers was not well known.

Plaintiffs will counter that argument by saying the Church knew more than anyone else about the problem. The Catholic Church got its first clue about pedophilia in the mid-1960s, when the Servants of the Paraclete, a religious order established to help troubled priests, noticed an alarming number of “sexual addiction” cases. The order began studying the matter, and in 1976 opened the Paraclete treatment center in New Mexico. From its opening through 1984, the Paraclete had treated 200 pedophiles and ephebophiles, with bishops paying for their offenders’ treatments. In 1981, the Church opened a second treatment center, St. Luke’s in Maryland, which one year later was dealing almost exclusively with sex-abuse cases.

The Church was becoming [he foremost expert in the world on pedophilia, but secrecy, the fear of scandal, the unwillingness to blemish the image of the priesthood amid a priest shortage, and the overall denial of the troubling questions about the sexuality of clergy kept the hierarchy silent. The laity was never told of any threat.

The plaintiffs will contend that since the bishops were the ones sending their priests to the Paraclete, the national conferences they comprise (the USCC and NCCB) would have discussed the situation, particularly the fact that many of the patients were repeat visitors- hence the case for extending liability to those bodies.

But the Church insists that these conferences carry no authority over the autonomous dioceses and thus had no power to act even if they did know something. As defined by Canon law, the conferences historically have been merely consultive, not legislative, and therefore hold no responsibility for the policies and procedures of an individual diocese. But some critics, citing Canonical provisions for exceptions to the longstanding rule, believe that is just a convenient interpretation proclaimed to alleviate liability of the USCC and NCCB in today’s litigious society. The plaintiffs say that connected liability exists because, among other things, every one of the Does contributed money to the Dallas diocese, which in turn helped support these organizations. That money helps fund the various committees that study and advise the diocese on policies of concern to the Catholic faithful.

And plaintiffs are using the existence of one of these committees to support their belief that a major, organized cover-up of child molestation in the Church has been in the works on the national level for more than 10 years. The allegation relics on a secret internal document from 1985. Co-authored by Father Tom Doyle, the 92-page report circulated among high-ranking Church officials offered a thorough analysis of the situation the church faced with sex abuse at the time. What it reveals is potentially incriminating knowledge of the extent of clergy abuse, as well as the early designs for a formal, top-secret Church plan to minimize the financial loss it anticipated as a result. The document, a proposal that was never officially approved, warned the bishops in 1985 that “In general, the adage that ’where there is smoke there is fire’ is almost always true.”

Projecting potential financial losses of $1 billion, the document calls for an extensive plan, referred to as the Project. It also recognizes that typical church responses to abuse allegations were allowing priests to re-offend, and addresses concerns that Canon law could be interpreted to establish interdependency between the dioceses and the national conferences. In an attempt to right past wrongs and prevent future scandal, the report gives advice to the bishops: “Failure to report the child abuse suspicion is probably the most common error.. .Clerics are never an exception to reporting laws. Our dependence in the past on Roman Catholic judges and attorneys protecting the dioceses is gone. ” Perhaps most damaging of all, the report warns that priests presumed guilty of child molestation “must never be transferred.”

The Project was to be funded by the NCCB and would be composed of very official-sounding groups, such as The Committee, The Group of Four, The Crisis Control Team, and The Policy and Planning Group. The proposal discusses “pre-intervention strategy,” for dealing with families, and instructs administrators to keep sex-abuse records in the secret archives. Furthermore, attempting to maintain the Project’s secrecy, the document makes a provision for all fees to be paid by a trial lawyer; since the courts generally honor the confidentiality of attorney transactions, this maneuver would prevent victims’ attorneys from obtaining hard evidence that the Project existed. Doyle and his team also warned of the potential for even greater scandal if the document fell into the wrong hands: “The necessity for protecting the confidentiality of this document cannot be overemphasized. . .Security for the entire Project is extremely important.”

The Project, plaintiffs attorneys will say, proves that the bishops and the national conferences not only fully understood the threat of pedophilia, but also had the resources and authority to deal with it-and did not. For those reasons, they will argue, the Church should pay dearly for what happened to children like Tommy at the hands of priests like Rudy Kos.

FATHER KOS USUALLY BEGAN MOLESTING BOYS WHEN THEY were 11 or 12, but the abuse often continued well into their teenage years. Tommy, for example, was a fifth-grader when he met Kos. His mother introduced him to the priest because he was having behavioral and emotional problems at home-normal family problems made more severe by a father who was often gone. She hoped Father Kos would make a good male role model for her son, and that Tommy would like him as a counselor. To the young boy, the friendly priest seemed pretty cool for a grown-up, and he easily persuaded Tommy to become an altar boy, which thrilled his parents as he was following the example of both his father and his older brother.

Almost every day after school Tommy raced to the rectory on his bmx bike, a black and yellow Mongoose with no pads and mag wheels. He wanted to be next in line to play Father Rudy’s Nintendo. Being part of the then 37-year-old priest’s inner circle had its benefits: Kos owned a personal computer and a bookshelf stocked with what seemed like an infinite supply of Ding Dongs and Jelly Bellies. “Rudy was on our level,* Tommy told me recently. “And he was great for manipulating your parents. He always talked them into letting you get your way.”

Kos was especially popular with the altar boys. As director of altar service, he won their respect, friendship, and love. He wasn’t like other priests: He let the boys swear like sailors, could beat them at video games, and always was willing to buy them presents. Though he often acted younger than his age, this Mensa member had a keen mind and a knack for making the boys who were close to him feel special for being so. But he also ran a tight ship of an altar-boy program, asserting himself as an authority figure who commanded their reverence and obedience. After all, in their eyes, this man of God was in touch with their souls, and thus in some way could affect their destiny.

The boys came mostly to play his video games, but once in a while someone would go down the hallway with Father Rudy to a small, dark, sparsely decorated room, where the miniblinds were always shut. It was here, in Kos’ office, that Tommy would meet him for counseling, and it was here that Kos began abusing Tommy.

The sessions often started with a shoulder rub, or maybe some back scratching and then a foot massage. Kos often maneuvered his victim’s feet in between his legs and used them to masturbate. “He hooked into your soul and made you like it,” Tommy remembers. “He totally messed with your mind.” Eventually clothes were shed, all without saying a word. In “Rudy’s lair,” as he calls it, Tommy was confused and scared. After about six months, he finally left the rectory gang. Kos would have to pick a new favorite from the brood of boys huddled outside his room playing Nintendo.

That Kos had transformed the rectory into a clubhouse didn’t seem particularly odd to casual observers, however, because they assumed the kids were friends with a boy believed to be Kos’ son, a boy in his legal custody who also had a room in the rectory. Kos talked about their relationship in a 1984 Texas Catholic article, which now seems full of sordid ironies. “There was a need for a male presence and I got to like the kid,” Kos said of the boy he met while a nurse at Dallas’ Methodist Hospital. Asked how they made time for each other, Kos said, “It’s sort of unspoken. If we feel the need to get closer, we try and take care of that.”

As Kos moved from parish to parish, he left behind a trail of shattered young boys, emotionally devastated and spiritually depleted. Many, like Tommy, later struggled with drug and alcohol addiction. Others suffered from sexual maladies. Many were overcome by depression. And John Doe X, an All Saints altar boy abused over several years, committed suicide, shooting himself in the head in 1992.

IF THERE IS ONE EXPLANATION FOR KOS’ unchecked behavior, it may be the Church’s extreme fear of scandal, According to Canon law, bringing scandal on the church is a sin that should be avoided at all costs because it leads to spiritual ruin and gives birth to further sins. Scandal is dangerous, as it raises doubt among the faithful and threatens the Church’s mission. Practically speaking, since money from parishioners is essential to the Church’s operation and promotion of moral well-being, anything that could mean lower contributions to the weekly collection basket should be kept hidden from the laity for the greater good of the Church, and thus society. So when allegations against Kos mounted, diocese officials tried to squelch rumors and controversy by quietly moving him to other parishes.

Obviously, lawsuits and media attention make scandal difficult to contain. So when the potential for a suit arose, the Church tried desperately to head it off. When John Doe I, a former altar boy at All Saints, began considering legal action against Kos in 1992, diocese officials grew concerned that their problem might explode. The Church first learned of John Doe I’s intention to sue after his brother met with Kos in late September. According to John Doe’s deposition, Kos told the brother that if the boy would drop his attorney, Windle Turley, the vicar general would arrange for Kos to turn over to the boy a $50,000 trust fund. So the boy fired his lawyer and met with Father Duffy Gardner, Rehkemper’s replacement as vicar general, who said he knew nothing about Kos’ trust fund. John Doe I says that Gardner then put him in touch with the Church’s insurance agent, whereupon the boy proposed a $150,000 settlement. After weeks of delay, John Doe I believed he was being given the runaround. In January of 1993, he rehired Turley, who filed the first suit against Kos and the diocese four months later.

Only when threatened by a high-dollar case, the possibility of more to come, and the certainty of media coverage did the diocese finally take decisive action against Kos. In the fall of 1992, within 48 hours of learning of the very real possibility of a suit being filed, the diocese suspended Kos, sent him to the Paraclete, and reported him to law enforcement for the first time, even though state law requires immediate disclosure of information regarding suspected child abuse. The parishioners at St. John’s were told only chat Father Kos had left “to seek the help of God.” Rumors flew, but without word from the Church itself, many of the faithful denounced the hearsay as heresy. In December of 1992 Kos was allowed to temporarily leave the Paraclete and return to Dallas for Christmas, which is when he allegedly molested John Doe III.

SHORTLY AFTER, MY FRIEND TOMMY also began considering legal action as a step toward getting his life back in order. Initially he was hesitant about suing. “I didn’t want this to become the next personal injury craze,” he told me. But his fears of legal exploitation gave way to anger as he learned of other victims, as well as other perpetrators. Coming to believe that the Church he trusted so dearly was doing little to prevent future victimization, Tommy pressed forward with his own lawsuit in 1993. It was a case against Robert Peebles that infuriated him most. Like Tommy, John Doe I in the Peebles case was an altar boy. What he never learned until almost 10 years after the incident, however, was that this John Doe was his older brother. The brother’s story reveals how Church officials dealt with a molestation when they had the opportunity to intervene immediately.

THE BOY MET FATHER PEEBLES THROUGH his involvement with the Boy Scouts. Peebles was the diocese’s director of scouting and a close friend of the boy’s family, In fact, John Doe’s mother hemmed Peebles’ scoutmaster pants. Knowing the boy looked up to him as sort of a hero, Peebles invited him in 1984 to spend his spring break at the Army base in Ft, Benning, Georgia, where he had recently been assigned as a chaplain. The 15-year-old was particularly excited about seeing the base’s jump school.

Peebles bought three six-packs of 16-ounce Budweisers, a bag of potato chips, and a six-pack of Coke for the first day. “I intended to drink beer with him and be a 15-year-old with him, essentially,” insisted Peebles in his deposition. And though the boy didn’t understand why they were staying inside instead of exploring the base, he didn’t complain because he liked the idea of drinking beer with the priest. John Doe drank five of those beers, leaving him on the brink of passing out, while Peebles had the other 13.

Drunk, the boy began blacking out and crashed on the two twin beds that had been pushed together. Peebles then crawled in next to him and began rubbing his body before reaching around to stroke the boy’s penis. Peebles, 6’2″ and 200 pounds, rolled on top of him, ultimately grabbing the boy’s hips tightly while trying to penetrate him anally. John Doe remembers clenching his buttocks as he grabbed the side of the bed and tried to escape, but he couldn’t move. When Peebles realized he was awake, he stopped. The boy left the room and reported the incident to military police.

Confused and guilt-stricken, the boy was held at the base for a day and a half before being sent home. Church officials in Dallas were contacted, but his parents were not until he arrived back at All Saints. Another priest picked him up from the airport and called his parents. “He’s okay, but you need to come and get him.” His mother knew something was wrong, and with her apron on and her hands wet from peeling potatoes, she darted to the church.

Later that week, the boy’s parents met with the pastor, Monsignor Raphael Kamel, who explained that Peebles had made “inappropriate sexual advances” toward the teenager. He guaranteed it was an isolated incident, brought on by stress and alcohol. “This never, never happens,” Kamel told the devout Catholic parents. If there was anyone this family trusted, it was the highly esteemed Kamel, a personal friend and spiritual advisor who was also chancellor of the diocese. When he said it was a time for forgiveness, they forgave.

The family also met with Father David Fellhauer, the judicial vicar (and now the bishop in the Victoria diocese). He explained that Peebles was being sent to St. Luke’s, a “renewal center” in Maryland. “We take care of our own,” he assured them.

“He led me to believe [Peebles] wouldn’t be a priest anymore,” said the boy’s lather, so they were ready to accept Kamel’s apologies and drop the matter. But Peebles was not out of trouble yet; the Army wanted to court martial Capt. Peebles and send him to Leavenworth for 20 years. Confused about whether or not to let their son testify, the family continued seeking the advise of Kamel, who warned them that the exposure could bring great scandal on the church and cause dissension at All Saints, the parish they helped found, having donated thousands of volunteer hours and tens of thousands of dollars to build it.

“The church was our life,” said Mrs. Doe, the niece of both a Dominican priest and a nun. “I wouldn’t scandalize the church.” The father, told this was an attempted molestation and not a sexual assault, didn’t think the Army’s punishment fit the crime-especially since he was led to believe this was an isolated incident. “I thought he put his hand on his knee or something.” He didn’t know there were claw marks on his son’s hips from the priest’s trying to force himself into the boy’s anus.

Meanwhile, John Doe really wanted to testify and see Peebles criminally prosecuted. But as a minor, that decision was legally left to his parents. Trying to decide between a son they loved and a church that to them defined love, they sent the boy to be evaluated by Ray McNamara, a clinical psychologist whom they had been seeing for marriage counseling. The parents claim Dr. McNamara convinced them that testifying would be extremely traumatic. So the father then drafted a letter to the military explaining that the family no longer wished to pursue the court martial.

The Army allowed Peebles to resign with a less-than-honorable discharge on Good Friday of 1984. He was then sent to the Medical College of Georgia for treatment, and was released one month later after convincing the medical staff that this was indeed a onetime incident.

Upon his return to Dallas, the diocese, believing the medical report’s confirmation that the attack was an isolated occurrence, reassigned him to St. Augustine’s in Pleasant Grove. The pastor there was never notified of the incident, But Peebles did continue treatment in Dallas-with Ray McNamara, who, unbeknownst to the Does, had been working as a Church consultant on annulment proceedings since 1980.

Plaintiffs suggest that McNamara, named as a defendant in both Tommy’s brother’s case and Jane Doe’s case against Father Hughes, is a key piece to their conspiracy puzzle. Without access to private medical and legal records that attorneys now have, it is impossible to know the extent of his involvement. What is known, however, is that he treated victims who were unaware of his potential conflict of interests; and it seems likely that he discouraged them from testifying against their perpetrators. In a statement issued by his attorney, McNamara says he in no way acted unprofessionally, unethically, or illegally.

As Peebles’ psychotherapist, McNamara also was consulted in 1985 when Father Fellhauer and Bishop Tschoepe decided to make Peebles pastor at St. Augustine’s. The decision, the bishop later admitted, was probably a mistake.

In September 1986, Peebles acted out again, fondling a sleeping boy on a camping trip. Knowing the boy woke up, Peebles turned himself in to the bishop, who suspended him, reported him to Child Protective Services, and sent him to St. Luke’s in Maryland, where this time his evaluation revealed a more sordid past. He admitted that from age 17 to 37 he engaged in sexual activity with 15 to 20 children. (Years later, in bis deposition tor Tommy’s brother’s case, he said abuse happened only seven times,)

Among the admissions was a 1979 incident at St. Mark’s in Piano when he masturbated a boy on a camping trip, and another one there in 1980 where he performed oral sex on a boy. He once confided in the director of a clerical retreat, telling him in confession, crying, that he was consumed by guilt. Peebles claims the fellow priest told him “not to be overly worried that [you’re] harming anyone…the boys could bounce back.” Peebles believed the other priest was merely trying to stop him from crying, though the priest warned Peebles “it was something [he] needed to take steps to avoid.”

In a later psychiatric evaluation, Peebles seemed unrepentant. In a report sent to his superiors in Dallas, a psychologist wrote that she found “his degree of lack of remorse around the pedophilic acts which brought him to treatment quite remarkable.”

The Does knew none of this until 1989, when the mother overheard some women talking about another Peebles incident at St. Augustine’s. “You’re kidding me! Right here in Dallas?” she said with astonishment. “I’m going to talk to Monsignor Kamel.”

“I don’t know about that,” Kamel told her. “I’ll check into it and get back to you.” But the Does heard nothing further from him. Knowing Monsignor Kamel had turned seriously ill, they never followed up the initial inquiry. If he learned anything, they would never know. Kamel died May 19. 1992.

THE STORY OF TOMMY’S FAMILY IS NOT unique. In tact it follows a pattern discernible in almost all cases of child sex abuse by priests. The victims usually come from devout families who trust priests almost as they trust God. In most cases against Catholic clergy, pastors assure families the incident is isolated, and that the priest will receive extensive treatment. And in many cases, a psychiatrist employed by the church encourages parents not to let their kids testify in any criminal proceedings, just as McNamara is alleged to have done.

Over the past decade, the problem of sex abuse by priests has become a tremendous cross for the Church to bear. According to victims’ support groups such as Survivor’s Network for those Abused by Priests, about 800 of the 49,000 priests in America have been or are still involved in litigation. An additional 1,500 have some form of allegation against them.

Now, though, the Church seems to have learned a lesson about dealing with sex abuse cases. Bishops across the country espouse a new era of openness with parishioners and profess a renewed emphasis on providing first for the victims. The national conferences have issued numerous statements and suggestions to the dioceses, who in turn are formulating official policy on the matter. Dallas will have one by year’s end. Meanwhile, bishops are urging victims to come forward to diocese officials.

But the Church now knows what psychiatry has taught-that only a fraction of victims will ever come forward. Cynics say that encouraging victims to come forward to the diocese first is merely a public relations ploy to make the Church seem more responsive. And in reality, they claim, what seems like a new way of handling cases is just a cost-effective attempt to contain impending scandals.

A few dioceses, however, are indeed confronting allegations of abuse publicly and immediately. In the Belleville, Illinois, diocese, for example, Bishop Wilton Gregory has made it policy to share all charges with the laity. In his diocese, a single accusation results in an automatic suspension of the priest while the Church investigates. The bishop then holds meetings to inform the public of the situation and educate parents on how to notice possible warning signs of abuse. The Church then offers to provide therapy for anyone who requests it. The priests in the diocese applaud the bishop’s methods-not surprising in light of other cases around the country in which fellow priests often attempt to blow the whistle on suspected pedophiles only to see diocese officials allow them to remain in parish assignments. Of course, dioceses like Belleville are still the exception.

If the Dallas diocese has learned any lesson, the change should show in its handling of new cases that parishioners haven’t first heard about through the media. The cases against Kos and Peebles and Hughes are not the only incidents to have occurred in the Dallas diocese. The local Chancery has been aware of several more priests with substantiated allegations of abuse against them, but none has prompted any public comments from the pastors or Bishop Grahmann. In a deposition, the former superintendent of the Dallas Diocese Catholic Schools revealed the names of five priests the Church believed were sexually abusing children throughout her tenure, from 1967 tol991, that have yet to be made public. Attorney Mathis does acknowledge that the diocese settled earlier this year with a victim who said he was molested by a priest who is now retired. Nothing was said, according to Mathis, because of privacy concerns. But what about the rest? Some of the possible pedophile priests are still functioning with access to children-one is even head of a national Catholic youth organization. Yet the laity has been told nothing.

Father Doyle, the Canon lawyer, believes these cases illustrate that the Church’s proclamations of openness are a part of a cover-up designed to appease a disgruntled public. “This is nothing but damage control,” he says. “They’re just trying to defuse possible lawsuits.” Since his work on the Project, Father Doyle has become an outspoken critic of Church dealings with abusive priests. He insists that the Church as an institution is at fault as much as the actual perpetrators, and he chastises the United States Catholic Conference and the National Conference of Catholic Bishops for not trying to prevent abuse from continuing.

Defense attorneys for the national conferences are denying that their clients are legally liable for any policy or lack thereof. They claim that religious freedom is breached if the courts dictate what messages the Church should preach and determine what information the faithful should hear. Further, they are reminding the court that it is black-letter law that no one has any legal responsibility to affirmatively prevent harm to others.

However, the law has provided exceptions for situations where there is a special relationship between a victim and defendant, exceptions that the plaintiffs believe pertain to the Church because officials are entrusted to offer guidance to both victims and the laity. The clergy has that added responsibility, plaintiffs attorney Demarest contends, because they accept the role of shepherd bestowed upon them by the flock. Alluding to a court decision against the Boy Scouts of America, in which the national organization was held liable for molestations by their scout leaders, Demarest says: “We have imposed responsibility on everyone else whenever such a problem exists-schools, day care centers, the Boy Scouts. Why shouldn’t the Church be forced to follow the same rules of decency? If they had a reasonably prudent interest in society, at a minimum they would have better supervised the priests.” Morally, Demarest may be correct, but legally she’ll have to prove that claim in court.

CURRENTLY, NO ONE SEEMS TO KNOW the whereabouts of Rudy Kos, who has been suspended from his priestly duties and has been acting as his own lawyer since late 1993. His last known address was a private postal box in a San Diego mall.

Robert Peebles was officially laicized in 1989, a rare process releasing a priest from his vows that is done only with approval from Rome. The Dallas diocese (much to the outrage of many local priests) gave him an $800 a month living stipend on top of a $22,000 loan to attend Tulane Law School in New Orleans. He has yet to pay back the loan, but he did pass the Louisiana bar. Peebles is now married (to a woman who was an employee at St. Augustine’s) and practices law in New Orleans.

Tommy, now 24, has been sober for more than four years, In June, 33 months after the first complaint was filed against Kos, the Dallas diocese finally offered counseling to him and the other victims, regardless of pending legal action. His brother is continuing intense psychiatric treatment for post-traumatic stress syndrome, trying to overcome the night terrors and sexual dysfunctions that have plagued him for almost 10 years. Tommy’s parents have removed the vials of holy water from their home.

When the trials begin, no one will deny that the Dallas diocese and the national Catholic Church have made mistakes in past dealings with priests who molest children. But Catholic doctrine allows even those who suffer the most disastrous falls from grace to stand again. When the sinner admits his errant ways, the process of reconciliation can begin.

I remember the priests at All Saints teaching me that. But who will have to admit to these sins? That is for the court to decide. Even if secular justice does not extend responsibility as high as plaintiffs hope, families like Tommy’s will always know that they were betrayed not just by a priest, but by the religious institution to which they devoted their lives. As for the Church, the healing hand is held back by the deepening nail of litigation.

THE APOCALYPSE

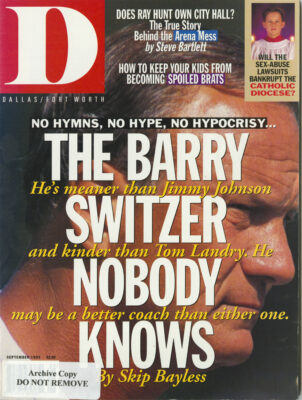

Can the Dallas diocese go bankrupt?

IS THERE A PATRON SAINT FOR GAMBLERS? IF SO, LOCAL Catholics should start saying novenas to him, because the Diocese of Dallas has embarked on the biggest gamble in its history. Church attorneys vow that they are ready to face in open court the 15 plaintiffs accusing local priests of molestation, even though the judgments against the diocese could top $150 million if the Church loses.

If the gamble works and the Church wins, it would escape paying even out-of-court settlements, which are the norm in these cases and average about $125,000 per plaintiff.

If the Church loses, however, huge judgments could wipe out the savings of every Catholic parish in Dallas, and their sanctuaries and schools could be sold to pay for the wrongs of a few priests. Unlike most other religious denominations, individual Catholic churches are not separately incorporated, Instead, following Papal guidelines, church holdings are centrally owned by Bishop Charles Grahmann. While such assets are extensive, available cash comprises only a small percentage of Catholic resources, and one local pastor with insight into tightly controlled diocesan finances says that difficulties could emerge if damages top the $5 million mark.

Not all arms of the Church are at risk. Prominent local Catholic institutions like St. Paul’s Medical Center, the University of Dallas, and some Catholic high schools operate independently of the diocese. Also legally distinct from the diocese is the Catholic Foundation, which has an endowment of over $44 million. Although its purpose is to donate to diocesan and other Dallas-area Catholic causes, and the bishop is a member of its board, the foundations separate status probably protects it from attack by the plaintiffs.

Catholic leaders will be faced with an array of difficult options if massive damages are assessed against the Church. Though the diocese collected $3.5 million for its charity operations alone in 1994, there is little spare cash in its budget, with most money invested in property or paying for ongoing operations. Using the savings of individual parishes would be one choice to meet the financial burden. The bishop could alternatively raid certain trust funds intended for schools and construction, or he could drain pension funds intended for priests and lay employees.

Facing such a disaster, the Dallas diocese might react as the Archdiocese of Santa Fe did in a similar crisis. The northern New Mexico archdiocese has been besieged by over 100 suits, mostly stemming from a religious center which was counseling priests who were known pedophiles and then releasing them into New Mexico Catholic churches in the belief that they were cured. Santa Fe has settled the great majority of these cases out of court, limiting the financial damage. Still, for neatly two years, the archdiocese has publicly and painfully flirted with bankruptcy, a step unprecedented in Catholic history. Archbishop Michael Sheehan, claiming that the payouts could total over $50 million, asked local parishes to contribute any money they could to a settlement fund. This appeal raised $1.8 million, far less than the total needed.

Church officials, scrambling to avoid bankruptcy, next turned to selling off land. “Once you get beyond cash and investments, all you’ve got is property,” says a Georgetown University theologian and priest. “Most property has got a school or a church on it.” In Santa Fe’s case, the most visible real estate sold was a diocesan retreat center. The National Conference of Catholic Bishops, in an effort to ease the strain on the diocese, donated for sale some New Mexico land it owned. Sheehan traveled to Dallas and elsewhere to beg the faithful to help bail out his flagging finances.

Santa Fe continues to try to force its general liability insurers to cover most of the damages. But insurers have balked at paying for past abuse, claim ing wayward priests were poorly supervised, that incidents were unreported, and that criminal activity was uninsurable. Furthermore, after the mid-1980s, when abuse reports became common, most insurers who wrote coverage for the diocese refused to write policies for employee misconduct, Accusations in Dallas stretch to 1992, so the diocese would definitely be on its own in paying such recent claims.

If the Dallas diocese were to run out of money to pay damages, it could be forced to file for Chapter 11 bankruptcy in an attempt to shield itself from closing schools and churches or curtailing charity operations. Such a move would be clouded by a fog of novel legal questions. According to tax rolls, the dio-cese owns more than $72 million of property in Dallas County alone. If abuse damages were substantial but less than the total assets of the Church, would a court allow it to declare bankruptcy? Could a court-appointed receiver confiscate the savings and property of each parish church, or would those not be counted as diocesan assets?

Whether bankrupted or not, the Church may be forced to sell some of its real estate. Before existing churches are sold, the diocese would probably dispose of its vacant land and investment properties. But this, too, would sting local churchgoers. Most vacant land is slated for future churches and schools in fast-growing areas. For example, the prime 50-acre Allen site that the diocese is holding for a new Collin County Catholic high school would likely be in jeopardy.

This nightmare scenario for the diocese raises another puzzling question. If judges shutter and sell local sanctuaries, would that breach the separation of church and state? Though he notes that church-state rulings take “surprising directions,” Tom Mayo, an associate professor of constitutional law at Southern Methodist University, doesn’t see a First Amendment question here.

“Bankruptcy protection, appointing a receiver, negotiating a set-dement for a penny on the dollar-those are secular activities of the state,” Mayo says. “That doesn’t involve interfering in doctrine, reviewing the bona fides of a minister, or anything like that. It’s just treating them as another nonprofit. Those are neutral principles. It’s not a question of being bad Catholics, it’s a question of ’you’ve run out of money.’”

However, Mayo does see a potential conflict if too many church assets are sold off.

“You can imagine the Catholic diocese being run out of business to the point where Catholics have no place to worship (in Dallas). I’d have concerns about running a legitimate church out of business.”

Bruce Pasternack, a New Mexico lawyer who has filed and settled more than 60 abuse suits against priests, finds such concerns preposterous.

“For the First Amendment argument to work, the Church would have to allege and prove that pedophilia is an essential part of the Catholic religion. To simply say that ’we’re a church and we’re above the law’ has never worked.”

So with a constitutional defense of church assets seemingly a remote prospect, what’s the contingency plan in case the diocese gets slammed with a big judgment? Apparently there is none. Bishop Grahmann is described by one Dallas priest as being “in a state of denial” about the potential bankruptcy of his flock. Meanwhile, as the cases get closer to trial, “judgment day” has taken on a new and frightening meaning for local Catholics. -Jeff Amy

THE SMOKING GUN?

Ten years ago, the Church knew it had a problem.

BY 1985, THE MAGNITUDE OF SEX ABUSE by priests was coming into focus for America’s Catholic bishops. Courts were awarding millions of dollars to dozens of victims molested by yet another priest, Gilbert Gauthe of New Orleans.

So Church officials embarked on a major effort to address the problem. In a secret 92-page document, they highlighted past flaws in dealing with incidents of abuse and proposed a multimillion-dollar plan to prevent future victimization and minimize the potential legal catastrophe. “At the rate cases are developing,” the report reads, “[Losses of] $1 billion over 10 years is a conservative cost projection.” The bishops, however, never approved its proposals.

Now that document has become a key exhibit for plaintiffs in the cases against Dallas priests. It may prove that the Church understood long ago the issues surrounding priest pedophilia. Plaintiffs hope it will also prove that a national cover-up was in the works 10 years ago.

Though the document is loaded with disclaimers insisting it is not a national policy, it does reveal that the Church was addressing the problem on a national level: “Some extremely serious issues… place the Church in the posture of facing extremely serious financial consequences as well as significant injury to its image. As a result of sexual molestation of children by clerics, for many months there has been continuous confidential communication amongst some expert consultants and clergy.”

The Church was recognizing the need for new ways to deal with abuse and to free the bishops from possible liability in the suits being filed around the country. Too often, victims’ attorneys were notifying the diocese about charges of abuse “only when [the bishop] has already been aware of sexual misbehaviors before and no action has been taken in the past except perhaps to move the cleric to a new assignment.”

The document also acknowledged “that perhaps those actions insofar as they aided, comforted or enabled the sex offender to continue his secret life were irresponsible and injurious…”

Such conclusions came from some of the Church’s most knowledgeable experts. The authors of this document were Father Michael Peterson, a medical doctor who was president of the St. Luke treatment facility for pedophile priests; Kay Mouton, the attorney who unsuccessfully defended the Church in the Gauthe case; and Father Tom Doyle, a Canon lawyer who worked at the Vatican embassy in Washington, D.C.

The three men called for the National Conference of Catholic Bishops to fund “the Project,” which would last for a minimum of five years. At the top of the Project’s organizational pyramid was The Group of Four. These bishops were responsible for contracting the services of professional consultants who would work with either The Policy’ and Planning Group or The Crisis Control Team, which was to consist of a trial lawyer, a Canon lawyer, and a psychiatrist. Together, they were to create a uniform policy to assist bishops with handling abuse in their own dioceses.

But the NCCB, believing such a major under-taking was unnecessary, rejected the Project. So Doyle then circulated copies of the document for each bishop to keep as a reference. In addition to pointing out warning signs of pedophilia, such as a cleric s sleeping in the same bed as a child, it advises bishops how to handle abusive situations. In mapping out this unofficial procedure, the document reminds them of the importance of “identifying all the victims and their families so that adequate intervention can be planned.”

This document also suggests that bishops ask themselves, “In which civil law cases should the diocese attempt to force its insurance companies to either settle cases quietly without public disclosure or, in the alternative, admit liability to prevent public disclosure of damaging information?”

Undoubtedly, the 1985 report reveals that the Church understood it was facing a dangerous crisis. Now, 10 years later, 15 plaintiffs in Dallas are wondering if this report can prove Church officials were plotting a major cover-up to conceal the ways they deal with their woes. -DM.