THE LEADERS OF ALMOST 20 INFLUENTIAL DALLAS churches filed into Mayor Steve Bartlett’s office one day last year, led by officials of the Greater Dallas Community of Churches, demanding to know what the city was going to do to help the homeless people living under the 1-30 bridge. They argued that the city shouldn’t be trying to bulldoze the makeshift shelters, though the motley collection of cardboard boxes and tarps was unsanitary and dangerous for the homeless, Bartlett explained that the city couldn’t allow the homeless to live under the bridge. Nor could the city pay to get them all apartments and the services they needed, The religious leaders adamantly insisted that something had to be done.

“Okay,” Bartlett said, passing around a yellow legal pad. “Each of you write down how many of the homeless your churches will adopt. “

At the end of the meeting, the legal pad came back with the names of a handful of churches on it. Not one of the church leaders who had demanded the meeting and were most vocal about the homeless had volunteered the resources of their members or their budgets to help.

This story illustrates the paradox of religious leaders’ attitudes toward charity in Dallas, arguably the most churched city in America; Sometimes it’s not the churches who talk about helping the poor who do the most. It’s not the wealthiest churches, the ones with the most to give, who devote the largest portion of their resources to benefit the needy. And willingness to commit resources to charity seems to have little to do with any particular brand of theology.

Pastors at most of Dallas’ largest Christian churches preach a conservative message drawn from Jesus’ words in the New Testament, about sinners’ need for salvation. But also consistent throughout Christ’s teachings is his command to help the poor: As you do unto the least of these, you have done it unto me.

Do Christians in Dallas expect Jesus to come knocking on their church door in a Hart, Schaffner & Marx suit? asks one preacher. “No, he’ll come as a beggar.”

Still, preaching and doing aren’t always synonymous. “The liberals cut all the miracles out of the Bible,” says the leader of one nonprofit agency that sponsors poverty programs. “The conservatives cut out helping the poor.”

“There is this sense in the conservative evangelical white community that you have to separate feeding people and the gospel,” says African-American minister Leslie Smith, pastor of North Dallas Community Bible Fellowship. “They are willing to fund agencies preaching to people, but not those feeding people.”

By one widely accepted estimate, about -40 percent of all Dallas residents say they attend religious services monthly “We’re a very active churchgoing population.” says Bob Buford, board member of the Dallas Leadership Foundation. “But that doesn’t necessarily lead to compassion for the poor. “

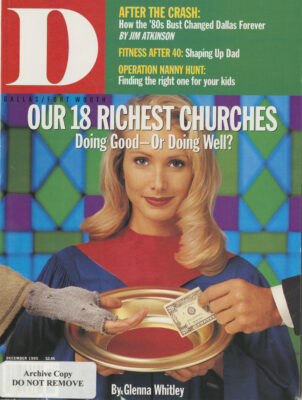

That compassion runs at high tide during the holidays-but what about the rest of the year? Churches’ budgets are not public records, so, choosing a cross-section of the community, we asked leaders of 18 Dallas churches-some of whose operating budgets run as high as $9 million-to tell us what they do year round for charity. We asked them to break out how much actually goes to help the poor, not to the many other missions and outreach programs to which churches give money, such as missionaries, evangelism, seminaries, or denominational donations.

As the saying goes, “Charity begins at home,” so we asked them to focus on what they do in their own backyard-how they serve the needy in Dallas, not in Chad or India. And we asked not only what portion of their operating budgets goes to benevolence, but where their members volunteer their time to benevolence projects.

What we found was surprising. How Dallas churches practice charity differs immensely from congregation to congregation, even within the same denomination. We found that total benevolence as a percentage of the operating budget varies from a low of about 1 percent (Oak Cliff Bible Fellowship) to a high of 31 percent (Prestoncrest Church of Christ.) Two churches-St. Michael and All Angels Episcopal (one of the largest and wealthiest Episcopal churches in America) and Highland Park United Methodist-refused to discuss their charity giving with us at all.

It’s arguable that charitable giving by churches is now more important than ever. Poverty seems to be growing. A new census report shows that Texas has the fourth-highest poverty rate in the nation; the number of people living in poverty in the state jumped from 17.4 percent in 1993 to 19.1 percent last year. At the same time. Congress is attempting to overhaul our flawed national welfare system.

As evidence mounts that faith-based nonprofit programs-like those run by Teen Challenge and the Salvation Army-attacking the roots of poverty are far more effective than government programs, churches can profoundly change the life of a community, strengthening faith and renewing hope more than any government effort can.

Knowing that welfare creates dependence and that well-designed volunteer programs can make a difference, Dallas churches appear to be undergoing a sea change. They are moving from “transaction” charity, such as giving gift baskets at Christmas and feeding the homeless at Thanksgiving, to systemic change-change that requires people to dig deep not only into their pockets, but into their hearts as well. It’s a change that makes some people very uncomfortable but can transform lives in a way no Christmas turkey can.

Loaves and Fishes

DURING A BREAK AT THE STEWPOT, THE DOWNTOWN SOUP kitchen for the homeless, Ben Beltzer sat down with “Big Mike,” a tall, 350-pound homeless man who earned money by working in the kitchen, where he could get paid at the end of each day. The short, middle-aged Beltzer doesn’t wear the garb of a priest, but the wooden cross on a leather thong over his casual shirt marks him as a religious man. Beltzer had seen the likable Big Mike off and on for several years, but knew little about him. He wanted to know more.

’’Mike, tell me about your personal relationship with Jesus Christ,” said Beltzer, who heads the Interfaith Housing Coalition and often volunteers at The Stewpot.

Big Mike got a thoughtful look in his eyes. “Oh, I guess I’ve been saved about 12 times this year,” he told Beltzer. Whenever he needed money or a place to stay, Big Mike picked a church and attended its Sunday worship service.

“I get down on my knees and cry crocodile tears,” Big Mike said. “They pat me on the back, give me $35, and I’m the illustration for that morning’s sermon.”

Big Mike’s salvation-as-panhandling technique hit Beltzer like a five-pound Bible to the solar plexus. But as a former pastor, he knew Big Mike spoke the truth. Many churches use benevolence like a carrot on a stick. “Come and eat at the soup kitchen, but first you have to listen to a sermon.” Or, “We’ll help you, but first you better get right with the Lord.” And, after all, making new believers is the purpose of most Christian churches.

Beltzer gave up being a pastor in part because of those attitudes. “The church is not to be a bottom-line organization,” he says, admitting that he’s now a “radical.”

But the Christian church does have a bottom line and that’s the Gospel of Jesus Christ. The dilemma comes in deciding which part of the gospel to emphasize: salvation or loaves and fishes? The soul or a full stomach?

Ask more than a dozen pastors that question and you get just as many answers.

“It is really not our job to feed the poor and house the homeless,” says the Rev. Steve Stroope, pastor of Lake Point Baptist Church, one of the fastest growing churches in the Southern Baptist Convention. “Our job is to make, inspire, inform, model, and facilitate-to create the kind of people who care about those kinds of things.”

Jesus said “the poor will always be with you,” points out the Rev. LaFayette Holland, pastor of outreach at Oak Cliff Bible Fellowship. “That means there will always be a need for ministry. You can do it from now to the day Christ comes. The difference in our area is we are going to be speaking from a Biblical point of view as it concerns poverty. We direct people back to the answer to their problems, their need for Jesus Christ. We never apologize for this. Our long-term goal is, without question, to get people saved, to get discipled to live like Jesus Christ lived.”

But at Oak Cliff Bible, those in need aren’t told that if they won’t accept Christ, they won’t be helped. “No, we’ll deal with their physical needs first,” Holland says.

Scripture is full of injunctions for Jesus’ followers to help the poor, says Dr, Howard Clark, pastor at Northwest Bible Church. By this alt men shall know that you are my followers, by your love for one another and Love the Lord thy Cod and thy neighbor as thyself Helping the poor is an integral part of the message of salvation, Besides, how can a hungry man think about things of eternal significance?

African theology doesn’t make a sharp delineation between physical and spiritual needs, says Derrick Harkins, pastor of New Hope Baptist Church. “Don’t you dare go out here on Oakland and tell a kid who has no hope that all he needs to do is pray and everything will be okay,” Harkins says. “You need to show him.”

Helping the poor is not an option or an elective for Christians, says Allen Walworth, pastor of Park Cities Baptist. “It’s part of the core curriculum of the church life, a non-negotiable expression of God. ” As such, charity cannot be given conditionally-only to the poor who prove themselves worthy by joining a church or “getting saved.”

“Jesus taught us to be as the Samaritan who found the man beaten on the side of the road, ” says the Rev. Jack Graham of Prestonwood Baptist Church.”The focus of the parable is who is my neighbor? Anyone who is in need is my neighbor.”

The goal of Prestonwood Baptist, he says, is to become a church without walls, beyond ethnic and racial lines. “When I came to the church six years ago,” says Graham, “I felt we should emphasize benevolence more.”

The Catholic Diocese of Dallas runs benevolence programs such as medical clinics, counseling services, and Headstart programs through its Catholic Chanties agency, which receives 7 percent of the money raised for benevolence by the diocese, Nonproselytizing, allprograms accept Catholics and non-Catholics alike. “We don’t believe it’s a nonre-ligious thing, however, ” says the Rev. Monsignor Kilian J. Broderick, executive director of Catholic Charities, “We believe the work we do gives testimony to the faith that underlies it.”

Jesus was a servant, says Andrew Adair, minister of evangelism and missions at Highland Park Presbyterian. “At the very heart of the gospel is the call to give ourselves away.”

Most of these churches cater to the relatively well-to-do. God demands more of the affluent, pastors say. To whom much is given, much will be required. “Jesus didn’t make people feel guilty, but he challenged the rich,” says Prentice Meador, pastor of Prestoncrest Church of Christ. “They have much more responsibility to the poor. But you don’t compel people to give money. You touch their hearts with human need. You inspire them. “

Still, a lot of giving that goes on at Christmastime, Clark says, simply salves the conscience. A $100 Christmas basket to a needy family down the block or a donation to a food pantry can make someone who does little the rest of the year feel like the repentant Scrooge after the visit of the last ghost in A Christmas Carol.

Surveys show that in terms of percentages, the more affluent give less of their income to charitable causes than do the working and middle class. Maybe the less well-to-do are closer to understanding what it’s like to be poor, more ernpathetic with those struggling to make ends meet. “Once people begin to acquire, they sometimes have a hoarding reaction,” says Sandra Hitz, director of outreach ministries at First United Methodist.

“One of the main idols in Dallas is security,’1 says Bill Bryan, pastor of Lovers Lane Methodist Church. “If security is your God, you are more selfish.”

And some people literally don’t see the pockets of poverty around them. “You can live in Dallas and not know someone in need financially or educationally,” Bryan says. But those at Lovers Lane can’t escape knowing about surrounding poverty. Bryan, who was pastor of Grace United Methodist Church in the inner city for 12 years, often brings that church’s needs to the attention of his parishioners. “Grace was in the middle of the problems,” Bryan says of his former church. “Lovers Lane has to seek them.”

Leslie Smith of North Dallas Community Bible Fellowship preaches to a church with both blacks and whites in the pews. Motivating his flock-mostly young families without a lot of discretionary income- to give to the needy isn’t always easy. “People are project oriented,” he says. “One way to keep income up is to always have a project.”

How does a church balance its own obligations with the desire to help those outside its borders? “The drama in most churches is how you allocate resources between missions and the needs within die walls of the church,” says die Rev. Bruce Buchanan, pastor of The Stewpot. “Many churches are grand edifices that need to be maintained.”

In the first century church, those believers who had means would sell even their primary dwellings and bring the proceeds to the church to help those within the church, and then those on the outside. Leslie Smith points out that when thousands massed to hear Jesus Christ preach, he didn’t send them away hungry, but performed a miracle with five loaves of bread and two fishes.

“I believe that was a lesson that we have an obligation to the larger community,” Smith says. His fledgling church set aside 10 percent of its operating budget to help those in need. This year, the majority of those funds will go to support a family from South Africa; the husband attends Dallas Theological Seminary. For a church that recently built a new facility and still needs furnishings and other equipment, tithing 10 percent for charity requires sacrifices.

Buildings say a lot about congregations-their values, their resources, their history. The magnificent architecture of churches like Park Cities Baptist, Highland Park United Methodist, and Highland Park Presbyterian, the gleaming marble and stone and beautiful stained glass windows surely awe and inspire their congregations. It can cost $20,000 to $25,000 per year for the largest churches just to maintain their grounds, says Douglas Smellage. owner of Lawns of Dallas. His company takes care of the lawns and flowers of 10 to 15 churches in the Park Cities and North Dallas.

Even at smaller, less impressive places of worship, the largest portions of many church budgets go to the building and upkeep of church sanctuaries and other facilities. One pastor estimates that most churches must spend at least one-quarter of their budget on the repair and maintenance of buildings and grounds, not that much different from what most families spend on their homes.

That doesn’t include [he capital improvements and the debt service those beautiful new buildings often create or the renovations that the old facilities need to remain safe and functional. (One of the main buildings at Highland Park Presbyterian dates to 1928.) And the more successful churches are, the more buildings they need. According to one source who often works with St. Michael and All Angels Episcopal Church in University Park, the church did not respond to our requests for an interview because they have eliminated most charitable giving in order to pay the debt service on a new building.

There’s nothing wrong with beautiful buildings and grounds. Successful churches must have facilities for the programs that meet their parishioners’ needs. The fast-growing Oak Cliff Bible Fellowship on West Camp Wisdom Road, for example, recently dedicated a new $6.5 million sanctuary and will soon open an education wing. It now owns 56 acres around the church.

Not only do those beautiful facilities cost money, but there’s increasing pressure to offer programs.

“People shop for churches,” says the Rev. Blair Monie, pastor of Preston Hollow Presbyterian. ” No longer are we Lutheran or Presbyterian forever. Churches are under pressure to meet the needs of the people. “

That may involve providing a variety of different worship services, support groups, children’s programs, choirs, drama classes, and 12-step programs, not to mention Bible studies and Sunday schools. Sophisticated programming costs money. Often, gifts to charities come from what is left over.

Striking a balance between providing facilities and exciting programs for members and donating funds to chanty can create conflict. Most large churches have budgets almost as complex as major corporations: Other budget demands include salaries, insurance, health plans, educational materials, denominational apportionments, utilities, and office supplies, not to mention altar flowers and wine for the communion cup.

How much of their budgets should Dallas churches allocate to charity? At the initiative of the Dallas Citizens Council, a multi-ethnic group of religious and civic leaders called the Morals and Values Committee first came together in 1993 to discuss ways to encourage-well, morals and values. Out of their quarterly meetings came a challenge to Dallas churches (as well as synagogues and mosques) to consider allocating 50 percent of their resources to their own ministries and 50 percent to missions. The challenge has gone unmet.

“That’s a worthy goal,” says Hal Brady, pastor of First United Methodist. “On the other hand, you have to start with reality.”

In the 1960s, about 50 percent of the budget at Highland Park Presbyterian went to benevolence. But over the years, inflation and the cost of living have eroded that portion of the budget to about 20 percent, which includes gifts to seminaries, renewal ministries, camps, and conference centers. The portion of that which goes to the needy is lower: $700,000, or about 14 percent. About $300,000, or 6 percent, is given to the poor in Dallas.

Park Cities Presbyterian, which was created four years ago when a group from Highland Park Presbyterian split off over theological differences, is one church that has made a conscious effort to increase its giving to missions each year. PCP’s annual operating budget is $3.9 million. Its benevolence budget in 1995 was $1,140,668, or 29 percent, up from 18 percent the previous year. Local benevolence totals $379,511, or about 10 percent, which includes the salaries of four ministers whose jobs primarily involve helping the indigent.

“Our prayer is that our missions budget will increase,” says pastor Skip Ryan. ” Our target when we first came together was to be a 50-50 church. The tension is to build a budget so the basics of the church families’ needs are being met.”

It must be working; PCPC has managed to increase benevolence while at the same time raising $10 million in pledges to build an education facility. “We probably give too modestly to our own denomination,” Ryan says.

Preston Hollow Presbyterian set a goal for giving 34 percent of receipts to missions, a target pastor Monie hopes they will reach in several years when the debt on their most recent building is paid off. The church spent$1.8 million in 1986 to increase the size of the sanctuary and add a youth house and rooms for education. Church members pledged to give the amount needed, but the economic downturn of the late ’80s forced the church to borrow the money. Soon, freed of the need to pay $250,000 in annual interest charges, the church will redistribute the money within its budget.

“I’d love the day when we give away 50 percent of our budget,” says Monie, who adds that Preston Hollow probably will need more education space soon. “Yes, it’s possible. But in what period of time?”

Prestonwood Baptist, now in North Dallas, announced this summer that it is moving to Piano to build a $50 million campus, a massive financial undertaking. But Pastor Graham says benevolence will not take a back seat to the church’s ambitious expansion. Instead, Ross Robinson, the church’s missions minister, said the move, which is expected to bring in new members, should bolster the church’s ability to help the poor.

For those churches without a lot of income, 50-50 can be measured in both time and money, says Bob Buford, a board member of the Dallas Leadership Foundation, which has spearheaded the Morals and Values effort. Some churches may not have much in the till, but their members can make significant contributions with their volunteer hours. One of his main goals this year: To come up with a way to measure how people give their time.

The 50-50 group also wants Dallas churches to consider giving most of their charity to local needs rather than sending their money to help those around the world. First United Methodist Church, for example, sends most of its benevolence funds outside the city. Global benevolence totals $360,724; of that, $99,000 stays here. Preston Hollow Presbyterian spends $223,000 or 11 percent of its operating budget, on benevolence; of that, $57,000 (3 percent of the operating budget) goes to local groups.

Buford would like to see those numbers shifted to favor local needs. “What’s more appropriate than ministering in ’some other country’ you can hit with a nine-iron from your yard?” Buford says. “All I have to do is cross Central Expressway and I’m in a world of hurt”-a world of poor refugees and immigrants from all over the globe.

On the other hand, First Baptist Church spends most of its charity dollars at home;ol the $1.01 million it designates for benevolence, almost all-$890,400-stays in Dallas. Oak Cliff Bible Fellowships global benevolence budget of $50,000 goes almost exclusively to Dallas needs. Prestoncrest Church of Christ also emphasizes local giving, with more than half-$275,000-of its half-million-dollar total benevolence budget staying at home. “Nowhere do we see Jesus in the gospels raising funds to take care of people in some province of the Roman Empire.” says pastor Meador.

The “Roman Empire,” in fact, has arrived in Dallas. First Baptist Church works with eight different language groups-Spanish, Russian, Arabic, Hebrew, Laotian, Portuguese, Japanese, and Camcroonian French. “We do a lot of work with new immigrants,” says Lanny Elmore, director of First Baptist missions and outreach. “We help them with the immigration and naturalization process, getting them to doctors, finding housing,”

But church budgets don’t tell the whole story. Every church we talked to rakes up “special offerings” during the year for various concerns: disaster relief, like the Oklahoma City bombing, special medical emergencies, a budget shortfall at a children’s home. In some cases, churches take in almost as much in these special gifts as they have set aside for charity. At Prestoncrest, special collections bring in about $9,000 a month. At Park Cities Baptist, an estimated $830,348 goes into the collection plate in addition to the charity funded by the annual budget.

And many churches encourage their smaller groups-Sunday school classes, Bible groups, men’s and women’s service leagues-to find and fund their own special ministries, Some Sunday school groups work with Habitat for Humanity, Some raise money for AIDS care. Men from First Baptist Church downtown may descend with saws and drills on an elderly woman’s home, construct a wheelchair ramp, paint it, and be gone by the end of the day, the money for materials coming from their own pockets.

One of the fastest growing volunteer programs at Northwest Bible and other churches is one that has virtually no budget: Prison Fellowship Angel Tree, which provides gifts to children in the name of their incarcerated parent, who fills out an information form describing the children and what they need. The volunteers take the presents to the children at Christmas.

In its sixth year, Northwest had more than 1,000 volunteers involved in Angel Tree last Christmas. Many volunteers keep up with their families throughout the year. “It doesn’t only change the lives of those receiving, but those giving,” says Annie Stobaugh, co-coordinator of the program at Northwest.

Money follows hearts. More of the benevolence budget of Northwest Bible Church goes to global than local ministries, but pastor Clark says they’ve found that when people volunteer for something they believe in, invariably their charity dollars follow. The funds may never show up on a ledger sheet, but they are gifts of the church nonetheless.

But where does all that money go? And does it make a difference?

Inside or Outside the Fold?

THE YOUNG FAMILY SEEMED to have everything going for it: A comfortable but not ostentatious house in the Park Cities, two children in private school, the husband in upper management at a large and thriving company. When the husband made an appointment for counseling, the pastor wondered if marital strife had entered into the picture.

But the session revealed something perhaps more shocking. They were mortgaged to the hilt, making payments on two cars and tuition for two kids. When the husband lost his job, it all threatened to come crashing down.

Most pastors in North Dallas can tell a story like this. If charity begins at home, a church must first consider the needs of those under its wing. “People in North Dallas tend to act like they have more than they have,” says Clark, pastor of Northwest Bible Church. “Appearances are important here.” Thus affluent churches sometimes discover parishioners living a $100,000 lifestyle on a $60,000 income.

But Christianity doesn’t admonish churches to take care of those living beyond their means. It does encourage caring for widows and orphans-in today’s vernacular, single parents and children of broken homes.

“You will have educated, single mothers who live on the edge of poverty, ” says Bill Counts, pastor at Fellowship Bible Church. “They may look all right, but they have no reserves. They spend every paycheck. If their child support is late or their car breaks down and they can’t fix it, they’re in trouble.”

Churches rarely bail out someone in major financial trouble, but most help strapped parishioners with utility payments or emergency car repairs. At Northwest Bible, parishioners in need can appeal to the “Mercy Fund,” administered by a small group that handles all such requests confidentially- The church also runs an employment network, and financial and personal life management classes for those with chronic financial problems. And there’s “Hand In Hand,” a widow’s support group that sometimes gets involved in solving money problems.

But at most large North Dallas churches, charity involves giving to those in poorer communities, where primary needs of food, housing, and clothing often go unmet. Determining who gets what, in a shifting landscape of competing needs, is not always easy.

Charity dollars often flow to the most visible victims of poverty, such as the homeless, who evoke feelings of compassion (if mixed a bit with frustration) because of their terrible living conditions and obvious desperation. Three downtown churches-First Presbyterian, First Baptist, and First United Methodist-fund major programs to help the homeless.

The Stewpot, started by First Presbyterian 20 years ago, serves breakfast and hot lunches and provides a variety of other services for the homeless, including a drug and alcohol abuse program, a dental clinic, counseling, and an employment program. The Stewpot has bought booster seats in recent years in response to the increasing number of homeless children. In an attempt to break the cycle of poverty, Stewpot’s staff and volunteers work closely with City Park Elementary to care for inner-city and homeless children, They sponsor “Saturday School” for those children, which includes games, computer classes, and music and art programs; and they pay tuition for stu-dents who goon to college. They even sponsor an inner-city Boy Scout Explorer Post.

First Presbyterian funds $136,263 of The Stewpot’s budget; the remaining $600,000 comes mostly from individual donations, other churches, foundations, and corporations. The Genesis Women’s Shelter for battered women and the Austin Street Shelter started at The Stewpot.

First United Methodist runs a program called First Saturday, which invites the homeless for a worship service, fellowship, and a hot lunch, and also provides sack lunches on other days for those living on the street. The church received a $25,000 grant from the city to help prevent homelessness. Homeless people have joined both churches and one teaches Sunday school at First United.

While about one-third of the 300 regular volunteers at The Stewpot attend First Presbyterian, the homeless mission attracts volunteers from many Dallas churches. A group of women from Reinhardt Bible Church has dished out food there every Wednesday for 10 years. But around the holidays, The Stewpot always needs more help-and money, Compassion fatigue and the competition for the charity dollar have hurt donations at many homeless programs this year. “People are tired of seeing homeless people, especially when they are bogus,” says Buchanan, who heads efforts at The Stewpot. “They see the people on street corners gathering money, then going to the liquor store.”

Prestonwood Baptist focuses on another “inner city.” The church provides bus service for “Saturday MorningCity Church” to children who live in a large area of low-income apartments in old Richardson. Volunteers from the church also are setting up apartment churches for the families in game rooms or community centers. “We want to get out of their faces and into their shoes,” says Ross Robinson, minister of missions.

Here’s another story most pastors in Dallas can tell:

A shabbily dressed man and a woman, with three small, unkempt children trailing them, come to the church door on a Friday afternoon. They say they’ve been evicted from their apartment and have no money for rent or groceries. Can the church help?

In its previous location near a bus stop. Fellowship Bible Church often had homeless people drop in asking for money. ” We’ve learned through bad experiences to be careful about giving out cash,” says Bill Counts. “Instead, we had food certificates and canned goods on hand.”

Most churches have an emergency fund or a food pantry for such needs, but ministers are aware that while many who ask for help are genuine, some are con artists who go from church to church to fund irresponsible lifestyles or drug habits. “It’s easy to develop a jaundiced view of the poor, especially beggars, ” says Leslie Smith of North Dallas Community Bible Fellowship. “Since we moved to a more visible location, we get requests all the time from people.”

Rather than turn deserving supplicants away empty-handed, in recent years Dallas area churches have banded together to meet the needs without encouraging streams of panhandlers at their doors. Many pastors now refer requests for help to a neighborhood center like North Dallas Shared Ministries, which helps the needy with everything from food to housing to finding specialized services.

“We cannot differentiate between those who are really in need and those trying to rip oft the system,” says Monie at Preston Hollow Presbyterian. After they became known for giving money and goods to the needy, they were inundated by requests, “The agencies check out people, so those who are truly in need can be helped.” Every year, Preston Hollow gives S8,500 to North Dallas Shared Ministries; four times a year the church collects food donations for the NDSM. Forty-three other congregations support the NDSM as well.

Funded by local churches and civic organizations, 31 church-based neighborhood centers scattered throughout Dallas now assist up to 10,000 families per month. While many churches still maintain goods for emergencies, the system relieves churches with little space of having to stockpile a food pantry or clothes closet.

“We’re getting smarter” about meeting needs, says Tom Quigley, outgoing executive director of the Greater Dallas Community of Churches, under whose aegis 314 congregations have banded together to address common concerns. Together, they can do things that would be difficult to do alone, such as creating the pastoral care department at Parkland Hospital and paying the salary of one of its chaplains. This year, the GDCC’s “Summer Feeding” program provided lunch and an afternoon snack for 30,000 poor children, five days a week for two months at 223 locations around Dallas. During the school year, the students get free or reduced-price meals at school. At many of the locations, churches provided enrichment programs and tutoring as well. This summer, churches and foundations provided about $100,000 to expand the program.

By working with other agencies, some churches have broadened their ability to respond to emergencies. Prestoncrest Church of Christ, in a partnership with the city of Dallas, has a program called “Homes For the Homeless.” Prestoncrest has completely or partially furnished 25 to 30 Steppington apartments, which are supplied by the city. One Sunday, Prentice Meador of Prestoncrest Church of Christ announced that a homeless single mother with two babies needed one of the apartments. By that evening, she had two beds, towels, linens, and all the baby gear she needed, plus $2,500 to complete the furnishings.

Harv Oostdyk, director of the STEP (Strategies To Elevate People) Foundation, points out that the homeless population makes up only a tiny sliver of the problem of poverty. The larger quandary: The enormous number of people who live a welfare check away from being on the street, and the cycle of poverty that entraps them.

Breaking that cycle defines the direction most Dallas churches are going-changing people’s lives by attacking the problem at its roots through volunteering to mentor, teach, train, and nurture people out of poverty.

“I hear very little interest in churches about doing the holiday basket-type thing,” says Tom Quigley. “They want to be more effective.”

The Team Approach

THE TYPICAL CLIENT OF THE INTERFAITH HOUSING COALITION is a homeless single mother with several children. When a new family comes to the IHC offices on Ross Avenue, they meet their 10-person ministry team, all volunteers, who are ready to help them get back on their feet. The adults asking for help (the transitional housing program is open only to families in which one or two of the parents are present) must be willing to meet the requirements of the program, and the ministry team holds them accountable.

Interfaith uses several apartment buildings in East Dallas for transitional housing and training. The grounds are carefully kept, with bright flowers and a nice playground for the children. Each apartment is furnished with donated furniture and decorations and filled with homey touches like fresh flowers and art on the walls. For the clients, most of whom arrive with little more than a garbage bag stuffed with a few belongings, the apartments are a sign that someone cares.

Two volunteers (they work in pairs) clean and prepare an apartment for the arrival of the family. Two others work with the children. Another pair counsel parents on finding and holding a job. The budget ream trains them to manage their finances. And last, but not least, the parenting skills team teaches the parents appropriate ways to encourage and discipline their children.

It’s a labor-intensive operation: Teaching personal responsibility to grown-ups who have never learned it on their own, But, as director Ben Beltzer says, its also a labor of love. About 70 percent of those accepted complete the 90- to 120-day program successfully, finding jobs and moving into their own apartments.

Many of the volunteers at Interfaith Housing Coalition attend Highland Park Presbyterian, Park Cities Baptist, and Park Cities Presbyterian, Many other churches donate funds. But Beltzer points out that some sponsoring churches that have been generous with money and volunteers hold back in some ways-refusing, for example, to let Interfaith children play basketball in the churches’ gyms. Interfaith used to hold a celebratory banquet at one large church to congratulate successful residents and thank volunteers. They discontinued the fete because the church charged so much for the use of the hall.

“Park Cities Baptist and First Presbyterian are two of the churches that don’t charge us to use their facilities,” Beltzer says. “I look at these mammoth churches that use their space one day a week. Shouldn’t it be a refuge?”

Beltzer has made numerous presentations over the years to churches, asking for their donations and volunteers. He says that Episcopalians and Presbyterians are the most generous, while Methodists and Baptists are the toughest sell.

Highland Park Presbyterian likes working with the Interfaith Housing Coalition because the ministry addresses the needs of the whole person. “We provide bridges for people to do that,” says Andrew Adair, minister of evangelism and missions. It’s an old cliché-don’t give a man a fish, teach him to fish.

“The greatest thing disadvantaged folks need is not entitlements, but someone to be their friend,” Oostdyk of the STEP Foundation says. “Some people in poverty feel ’I’m covered with shame, I’m filled with guilt, I have no purpose in my life, I am lonely.’ These giant systems [welfare] can’t possibly change people’s lives.”

At First Baptist Church, a new ministry got underway this fall: A trade school with volunteer instructors who will teach unemployed and low-income workers carpentry, plumbing, electrical work, and brick-laying. The 160-hour program is designed to give every student who passes a guaranteed job making $7.50 an hour. (Several contracting firms have pledged to provide jobs for graduates.) After a three- to six-month probationary period, the students will go on to apprentice school.

Still, motivating affluent, well-educated people to volunteer time can be challenging. “It’s easier for them to give money than their time, their abilities, their hearts,” says pastor Meador of Prestoncrest. The church initiated JobNet about two and a half years ago to help the unemployed lor mis-employed) find jobs. Church members trained in job counseling, therapy, or networking meet on Wednesday nights to support, coach, nurture, and help strengthen the faith of those looking for work-people who can get very depressed.

Meador motivates people to volunteer through encouraging sermons and moving stories. At Park Cities Presbyterian, each new member goes through a class and is encouraged to assess his or her “gifts” of service. At Oak Cliff Bible Fellowship, anyone waiting to become a member must agree to serve-somewhere, somehow.

Finding volunteer opportunities for churchgoers sometimes means pushing them out of their comfort zone across racial and cultural lines, says Kurt Neale of Northwest Bible Church.

But pushing people too far outside that zone can backfire. This year, HP Presbyterian had to switch its tutoring program from Fannin Elementary in East Dallas to Sudie Williams in Bluffview because many of the volunteers feared the area around Fannin was not safe.

The same thing happened at The Stewpot. “In the past, The Stewpot had the reputation of being a rough place to be,” says the Rev, Bruce Buchanan. Though he never felt in danger, he admits that “perception is reality” and acknowledges that The Stewpot’s grimy look fostered that feeling.

After a disturbing incident with a policeman and an out-of-control client, Buchanan undertook the “de-institutionalization” of the mission. He had the place power-cleaned, pried open the windows to let in light, bought new round tables to replace the cast-offs, lugged in a piano and recruited a client to play it, and started an ID program. “It changed the whole environment,” Buchanan says. “Our incidents were reduced over 90 percent. ” But he’s careful to say problems sometimes still happen. Police officers monitor lunch times.

It has been especially hard to get white churches to volunteer in the South Dallas-Fair Park area, says Tom Quigley of the GDCC. Though half the people there live below the poverty line, only 4 percent of them go to the local food pantry for assistance. “The poorest areas don’t have as much food, money, or volunteer time donated,” says Quigley. That problem points out a major weakness in relying on private benevolence to help the poor.

“Obeying God is never risk-free,” says Adair. “But fear of personal safety is a big issue. It may not be necessarily true, but you have to meet people where they are, A big part of urban ministry is helping people overcome fears.”

Voice of Hope

OVERCOMING FEARS HAS LONG BEEN KATHY DUDLEY’S MISSION. Dudley, founder of Voice of Hope, vividly remembers the days when local churchgoers would drop off a carton of clothes at her family’s front door. As a poor teenager, she would delve excitedly into the box, hoping to find clothes she could wear to school, only to find dirty cast-offs full of holes and the wrong size to boot. She’d sit and cry in frustration. Perhaps the givers meant well, but the gift involved no real contact or compassion between the givers and the person in need. That kind of charity, say some volunteers, is almost worse than none at all because it robs the recipient of dignity, creating anger and bitterness instead of gratitude.

Too often, Dudley says, that’s how Dallas churches approach charity-giving money or goods without giving of themselves. Many of the churches working with the poor are small, unorganized churches with lew resources other than a willingness to serve. From the point of view of those in need, Dudley says that it often seems that Dallas Christians are sharply split between those who have and those who have not.

“As a Door person looking at the churches in North Dallas,” says Dudley, “I would have a hard time seeing that they have their priorities straight. I would have a hard time, knowing the Bible, to think they were reading it.”

Dudley, who is white and lives in a black neighborhood, says that to some extent, racism plays a role in some Dallas churches’ refusal to get involved in poverty programs.

“But economics issues and classism may be the bigger challenges,” she says. In fact, it’s easier for groups like Voice of Hope to get middle or upper class whites to volunteer than middle or upper class blacks. “It’s hard to say, ’I want to go back,’ ” Dudley says.

Dudley broke her family’s cycle of poverty by getting an education. She married a very successful executive search consultant and for years lived in a comfortable white suburb of Dallas-far from the privation that plagued her early years. But in the midst of her cushy life, she began to experience a “deep call from God” to take what she learned in an impoverished childhood and use it to transform other poor people’s lives. Dudley designed a paradigm around one basic question: What did she-and other poor people–need to succeed?

She and her husband sold their home and moved into the inner city near the West Dallas housing projects, where they are the only white family on die block. Dudley started Voice of Hope, a nonprofit agency that seeks to transform West Dallas from the ground up by providing a liaison between those with desperate needs and those with the desire to give. Her ability to create that structure and its slow but obvious success has attracted donations from many large Dallas churches.

Dudley tools around the neighborhood in a minivan, pointing out the changes in the neighborhood since Voice of Hope began in 1982. Her 10-block target area has about 150 small homes; when Dudley first moved to West Dallas, most were sadly dilapidated, decaying under the weight of poverty and neglect, a symbol of the hopelessness in most of the residents’ lives. Many houses had been abandoned or condemned by the city, constant reminders that no one cared.

Now, some streets are showing signs of life. An old bungalow has been given a new porch and a fresh paint job. The trash is gone from another yard. And here and there are brand new houses, small but tidy pieces of the American dream boasting landscaping and iron benches on the front porches.

In just a few years, Voice of Hope volunteers, working with local teenagers, have done minor repairs on 39 homes, major renovations on two others, and built 11 new houses, which were sold to area residents who agreed to take a “homeowner’s skills” class. Slowly but surely, the neighborhood is being transformed from a place of hopelessness to a neighborhood where people sit on their porches and take walks at night.

But the heart of Voice of Hope lies in a renovated school, which provides children with after-school tutoring, Bible clubs, computer lessons, and a dentist’s office for free dental care. Students learn life skills and have paying jobs, which may include cleaning the school or mowing a yard. Today, Voice of Hope has 14 paid staff members and more than 600 volunteers, mostly from North Dallas churches.

“We got an incredible response from churches,” Dudley says, with far more people volunteering than Voice of Hope could realisdcally put to work. Funding from church budgets has been slower to follow. Of VOH’s budget, only about 8 percent comes from area churches.

Dudley insists on two things: Those who benefit must participate in some way-providing food for volunteers or wielding a hammer alongside them. And all charitable work must be geared toward building relationships, not just dropping into a neighborhood for a day, doing some work, then disappearing until the next time a need arises. “It has to be done in a way that doesn’t create dependence,” Dudley says.

Increasingly, partnerships of churches and nonprofit groups like Voice of Hope merge money and volunteers to attack poverty at its root, attempting to make systemic change by building up local leaders who know local needs. Dudley has resigned as director of Voice of Hope, passing on leadership to a black man from the neighborhood, She now is president of the Dallas Leadership Foundation.

“Self-help is die key word,” Dudley says. “Not a lot of churches start with the leadership that exists.”

For years, Northwest Bible Church has been involved in Eagle Flight, a Young Life Club for teenagers in West Dallas. Though it was started by white youth ministers, it’s been turned over to black leaders. “If we work with someone there, it is more effective than just throwing money over the Trinity River,” says pastor Clark.

“The goal is to empower, aid, and help them,” says Northwest minister Kurt Neale, “but it has more validity in that community if it has indigenous leaders. As much as possible, we try to keep our names off things.”

From Success to Significance

WALKING ALONG A LIMESTONE BLUFF ABOVE THE RlO Grande River, Bob Buford was gripped by the fear he would never see his beloved only son ever again. The cable television executive had flown from his Tyler home to Big Bend when he got the word: His son Ross and two companions had been swept away while swimming. One young man had been rescued. Buford hired planes, helicopters, trackers with dogs-everything money could buy-to find his son. But to no avail. Authorities found Ross’ body four months later.

Buford grew up middle-class, but his success as a TV entrepreneur brought him millions. The loss of his 24-year-old son-so promising, so committed to God-profoundly changed his life. With all his worldly success, he wanted to contribute more to the world, something of lasting significance.

He hasn’t given all his money away and taken a vow of poverty, but he now splits his time between Dallas and Tyler, working on private initiatives to encourage Christians to find ways to make real contributions to those in poverty. To that end, Buford joined other Dallas citizens in founding The Dallas Leadership Foundation and has written a book, Half time: Changing Your Came Plan From Success to Significance.

“I’m 50 years old,” Buford says. “I can expect to live another 20 or 30 years. Chronologically, boomers have a whole second adulthood our fathers didn’t have.” And as they live longer, they’ll live healthier lives. The question is, what will they do with those years?

Two secular trends-loss of faith in government and the dismantling of the welfare state world-wide-are melding with the boomers’ search for meaning and fueling the increasing levels of volunteerism seen in Dallas. ’It’s driving people to the social sector to find significance,” Buford says. “They cannot find it in their work. It’s not there to be found.”

As this trend gathers steam, Buford says the large, complex churches-like Preston-wood Baptist and Park Cities Presbyterian-will be able to provide these seekers with ways to use their knowledge and skills to help others. Larger churches can harness not only tremendous financial resources, but also training and the infrastructure to tackle systemic change.

As Buford goes to church leaders, encouraging them to bridge the gap between their churches and the communities in need, he says he has seen no frontal resistance. But he has seen passive resistance, churches simply choosing to keep their volunteers working within the church.

Helping the poor won’t happen by good intentions or reading the Bible, Buford says. But the Bible cannot be left out.

“The old social gospel separated the doing from faith,” Buford says. “The objection of the Biblically-based churches was the church then was just another social agency. There’s been a movement away from that toward a grounding in the Bible.”

How should churches start? By getting their members to devote 50 percent of their volunteer time to people outside the church.

“It’s not realistic to spend 50 percent of the budget for most churches, ” Buford says. “But time is very egalitarian. Bill and Hillary and the Pope don’t have any more time than you or me.”

Could the Church in America End Welfare?

THOUGH HE NO LONGER IS POOR, poverty is very real and personal to Leslie Smith, pastor at North Dallas Community Bible Fellowship. “I remember being on welfare,” says Smith, whose parents separated when he was quite young. A 10th grade English teacher had a profound impact on him, pounding into Smith the importance of communicating clearly. He went to undergraduate school on a full scholarship. He understands what poor people need. “I did not need a hand-out,” Smith says. “I needed a hand.”

Across town, pastor Tony Evans of Oak Cliff Bible Fellowship wants to give people that hand. In early fall, he asked at the end of a Sunday sermon: “How many people here are on welfare? We’ll get you off.” Several people around the auditorium stood up and began to walk toward the front of the room.

Evans makes it known that his church, which is 90 percent black, will do everything it can to help people obtain job training, find work, and gain the self-respect that comes from being a productive member of society, The church funds and provides volunteers for programs that provide GED tutoring, job placement, even a business incubator. They provide male role models for fatherless boys. And the church has adopted Village Oaks Apartment Complex, 600 low-income units, to provide services and training for those impoverished residents.

“Welfare stems not only from an economic reality but a mentality that says I am dependent and I am a victim,” says Evans. “Your commitment to be responsible is sucked right out of you. The church could eradicate welfare in 12 months, for those that wanted to get off welfare.” Evans feels two welfare programs should be retained: Medicaid and Aid to Families with Dependent Children. But he’s preached his church-could- end -welfare message not only in local sermons, but at major events like the stadium-filling rallies held by Promise Keepers.

Pastor Jack Graham of Prestonwood points out that churches used to take care of their own. “It behooves government, churches, and the corporate world to partner together,” he says.

Ministers at some predominantly white churches aren’t so confident that the church could end welfare.

“There’s certain things only the government can do,” says Bill Counts. “Churches, especially the larger ones, need to get behind more specialized organizations like STEP. It takes people with wisdom and focus to make a real impact. The private sector could do more than they’re doing, But it’s naive to say we’ll hand over the problem of poverty to the church and it will be solved. It’s not just money; it’s changing the culture of poverty.”

“The churches can’t individually do it,” says Les Smith. “But First Baptist of Dallas and First Baptist of Atlanta are flush with individuals who could make a major contribution that would go a long way toward ending poverty.”

“If the church decided to pool its funds, the whole economics of American culture could change,” Evans says. “It mans the largest volunteer force, has the most property, garners the most skills, and has the most money flowing through it. ” If every single church took in just one homeless person, he says, an enormous transformation could take place.

This, of course, assumes that every homeless person wants to be helped. But Evans has an answer for that: As St. Paul put it, be who does not work, does not eat.

Evans suggests a weaning process-seven years, perhaps, during which it would be crystal clear to everybody that welfare was going to end, leaving government as a fallback only for those so physically or mentally disabled they cannot take care of themselves.

Oak Cliff Bible Fellow ship’s pastor of outreach, the Rev. Holland, agrees with Evans, but adds a few caveats. “I don’t ever want to say to the United States of America that it doesn’t have responsibilities to its people,” Holland says. “People don’t think of payments to farmers as welfare, but it is.”

Government funding for private initiatives like those at Oak Cliff Bible Fellowship could go a long way toward ending poverty, he says. But if government money came with the condition that pastors not tell people about Jesus Christ, well, forget it.

“Christ,”saysHolland, “changes people.”

Get our weekly recap

Brings new meaning to the phrase Sunday Funday. No spam, ever.

Related Articles

Arts & Entertainment

DIFF Documentary City of Hate Reframes JFK’s Assassination Alongside Modern Dallas

Documentarian Quin Mathews revisited the topic in the wake of a number of tragedies that shared North Texas as their center.

By Austin Zook

Business

How Plug and Play in Frisco and McKinney Is Connecting DFW to a Global Innovation Circuit

The global innovation platform headquartered in Silicon Valley has launched accelerator programs in North Texas focused on sports tech, fintech and AI.

Arts & Entertainment

‘The Trouble is You Think You Have Time’: Paul Levatino on Bastards of Soul

A Q&A with the music-industry veteran and first-time feature director about his new documentary and the loss of a friend.

By Zac Crain