Dale Henson almost didn’t make it the night George Bush went over the top.

Channel 8’s evening news producer stomped through the control room, bellowing, “Where the hell is Hansen? Where the hell is Hansen?” Producers, reporters, and flunkies scampered about the building like children searching for a giant Easter egg. The night when the Texas delegation cast the decisive votes at the Republican National Convention was no time for the sports anchor to vanish. It could have been disaster. Very nearly was.

With seconds to go. though, Hansen skidded into his chair at the end of the anchor desk, riffled through notes scrawled by an assistant, and glibly delivered the day’s scores and highlights. Except for putting the New York Yankees in the National League, where they probably belong, his performance was flawless, and the television audience knew nothing of the crisis that could have been. But back at Louie’s bar, where Hansen had abandoned his eleventh beer minutes earlier, regulars gaped at the TV and spontaneously whooped a cheer.

Once again. Channel 8 dodged the bullet. Once again, the fairy godmother of television journalism smiled kindly at the Spirit of Texas on 8. Once again, the massive audience that ranks WFAA-TV as the most dominant news station in any major market in this country received a nightly report that was fast-paced, informative, and slicker than Troy Dungan’s bow tie.

This time, it was luck. Most nights, it is not. Over the past decade and a half, Channel 8 has slowly, carefully, deliberately constructed a local television news operation that is, by any measure, among the two or three best in America. While the NBC station, Channel 5. scrimped to make ends meet, and the CBS station, Channel 4, pinched pennies to squeeze out 30 percent to 40 percent profit margins for owners in Los Angeles, Channel 8 invested and built to overcome the disadvantage of its weaker network, ABC. and plant itself firmly as number one in Dallas.

“It’s no contest,” exclaims John McKay, who led Channel 4 when it was a contender in the early Eighties and now is president of KDFI. Channel 27. “It seems to me that Channels 5 and 4 have conceded the title and are squaring off for second place.”

For the first time that anyone can remember, one station-Channel 8-now thoroughly controls the airwaves in the critical business of delivering the news. And news, of course, is vital to the network affiliates, the big three of local television. Given the numbing sameness of entertainment programming on the networks, news shows offer each station its best chance to establish an identity, to set itself apart from the competition. Because many people depend on television for information about current affairs-more than 60 percent of adults say TV is their primary news source, according to some surveys-the nightly broadcasts also give the stations an opportunity to help shape the issues that shape the city. And a good local news show is a license to print money.

By any measure you can devise-payroll, equipment, out-of-town bureaus, staff experience, industry awards-Channel 8 is on top and likely to stay there. Whether it’s spending $12,000 on Byron Harris’s groundbreaking investigation of fraud and corruption in the savings and loan industry, or maintaining full-time reporters in Austin and Washington, or sending Dale Hansen or some other sports reporter to cover every day of the Cowboys’ training camp in Thousand Oaks, California, Channel 8 does what it take to get the stories.

“We always feel that the company will give us whatever it takes to do a good job,” says consumer reporter Bonnie Behrend. “They want to make a profit, but I don’t ever remember somebody saying don’t cover a story or take a shortcut because it would save money.”

But an open checkbook is by no means the only reason that Channel 8 leads the news pack in Dallas. That it is the only locally owned station of the big three no doubt helps a little. That management regularly meets with minority viewers and listens to their concerns certainly is a factor. That the station shows its heart with programs like John Criswell’s “Wednesday’s Child” and with thousands of hours of community work each year contributes to success.Haag’s enormous expectations create a condition that borders on panic. No one feels safe. Few see themselves as adequate.

But ask anyone associated with WFAA-TV to cite the biggest reason for the station’s news dominance, and you’ll hear the name of one man. He is news director Herman Martin Haag Jr. Marty Haag, to you.

If any single person can be called the driving force behind Channel 8’s rise to the top. it is Haag. His fierce desire to excel communicates itself to everyone at 8, from the star anchormen to the lowliest gofers. He manages by what has been called “creative tension,” and the emphasis is on both words. The creativity has its payoff in the soaring ratings, the tidy profits, the myriad national and local awards. As for the tension, it is everywhere. No organization chained to daily deadlines is without its pressures, but Channel 8 staffers may pay a higher price than many for their success.

Some in the Channel 8 newsroom blame the pressure for failed marriages, drinking problems, burnout cases, and at least two tragedies that struck the staff in recent years. They suggest that consumer reporter/anchor Jan Bridgman’s 1984 suicide by carbon monoxide poisoning and reporter Jack Ken-drick’s 1986 death by the same method were extreme manifestations of the tension that oppresses all of them. That he deliberately creates such tension, they say, is the dark side of Marty Haag.

•••

Marty just got so excited he couldn’t stand it,” says Bonnie Behrend. “He ran out in the rain to see the story for himself. Then he raced back into the newsroom and started screaming at the reporter over the two-way radio and shouting at everybody else, telling us all what we needed to do.”

The story was a ruptured gas main, not a major news event in the greater scheme of things. But it occurred only about two blocks from WFAA studios at the corner of Houston and Young, and for Marty Haag it was a rare opportunity. Usually, the news takes place farther away and Haag is stuck in the newsroom, seething in frustration because he can’t go where the action is. Channel 8’s veteran news director is a newsman’s newsman. He seems to love a good story better than good sex.

If you met him socially, you wouldn’t take Marty Haag for the excitable type. At fifty-four, Haag’s manner often seems tepid, his personality bland. He speaks in a slow drawl, choosing words thoughtfully and stroking his sparse pewter beard. He sometimes appears tired, absent-minded, possibly bored. This guy could be an accountant, you would think. Or maybe a shrink.

But that’s Haag’s public face. Place him in a newsroom when the world is ending outside and he becomes a dervish. His voice gains the force of an air-raid siren as he flings instructions, shouts reprimands, and stretches the limits of four-letter vocabulary. His arms windmill against the air, and staffers who have seen him fight the pressures of breaking news say he dances like a man on a fire ant hill.

It was Haag who insisted that the station cancel regular programming and stay with the story when Delta Flight 191 crashed at D/FW Airport in August 1985, a decision that cemented Channel 8’s position as the station to watch for important news. It was Haag who battled management in behalf of the sports investigation that halted SMU football for two years and earned the prestigious Peabody award for WFAA. It is Haag who has personally directed nearly every major story presented on his station in the past fifteen years.

“He’s incredible,” says Byron Harris. “I don’t see how he can keep up that kind of enthusiasm after all his years in the business. I don’t know where he gets the energy. I guess you could say that I regard Marty Haag with more than a little awe,”

In fact, practically everyone who has ever worked with Haag holds him in strange, ambivalent awe that combines equal parts affection and fear. Many call him “The Mountain,” apparently referring either to the peak lesser mortals must scale in order to receive divine commandments or to the one that would not go to Mohammed. Others refer to him as “The Angry God” or “The Volcano” and tremulously await the next eruption. To most, he is simply “The Haag.” an agnomen conferred in roughly the same tones with which the devout might pronounce “The Church.” All know that the Channel 8 newsroom is his exclusive domain; within it, his word is absolute.

Even WFAA general manager Dave Lane, Haag’s boss if you check the organization chart, speaks deferentially and a shade timidly of the man who is the acknowledged brains, heart, and soul of Channel 8 News.

“We went through several years after I became general manager when Marty and I didn’t get along at all.” says Lane. “We were fighting constantly, and he threatened to quit several times. But when you have a resource as extraordinary as Marty Haag, you learn to make certain concessions. You learn to get out of his way and let him do what he does. Marty built this news operation. It’s his newsroom, and he runs it.”

In fifteen years as news director, Haag did, indeed, build the organization that is Channel 8 News today. Not only did he develop top talent and insist on first-rate equipment, he also reshaped the concept of television news into something Dallas had never seen before and still finds all too seldom on other stations. Drawing on his background as a reporter for the San Angela Standard Times and the Dallas Morning News, Haag insisted on strong reporting above all else-Good pictures were gravy. It took Dallas viewers some years to appreciate the extra substance, but the strong information value Haag brought to TV news almost surely is the reason WFAA grew from a paltry also-ran to become the powerhouse of the market.

When then-general manager Ward Huey, now president of the broadcast division of A.H. Belo Corp., approached Haag about moving to Dallas as news director in 1973, Channel 8 consistently placed a distant third in local ratings, occasionally stumbling to a poor fourth behind a news program the independent station, Channel 11, offered in those days. Coverage was disorganized and shallow, but it hardly mattered because few people were watching.

“I remember being brought down here and looking at the broadcast, and the broadcast seemed awfully parochial,” Haag says of his interviews with Huey. “The emphasis was on drownings and fires. There weren’t any stories that really got into issues, nothing that really told Dallas what was happening to the city.”

Haag’s initial reaction was that the situation was hopeless. The cosmopolitan wave that brought sophistication to Dallas in the late Seventies had not yet rippled, and Haag knew from his days at the Morning News and later at WBAP radio that the city would settle for parochial mediocrity, even applaud it. Why should he abandon a promising career with a national network for a potentially frustrating job with a local station in the Southwest?

But as he flew home from his interview, Haag imagined the changes he would make as news director at Channel 8. “A new type of reporter needed to be hired,” he recalls. “I thought if I took the job, that would be my number one goal.” With that challenge in mind, Marty Haag came to Dallas.

As news director, Haag eased out the pretty faces, the youngsters in love with the romance of television, and the journalistic hacks who arrived each morning to inquire. “Whuddaya want me to do today?” To replace them, he sought journalists who could work like newspaper reporters, learning a beat, developing sources, and generating their own stories. His first few hires, he knew, would set the tone of Channel 8 News for years to come.

A flap over journalistic ethics at KWTV in Oklahoma City provided Haag with the nucleus of reporters he sought. A young reporter named Byron Harris had prepared a story accusing several Oklahoma City car dealers of overcharging, but KWTV management had refused to air it for fear the dealers, important advertisers, would be offended. Harris walked off the job, and eight other news department staffers soon followed. Harris. Doug Fox. and Tracy Rowlett were plucked up by WFAA. Marty Haag had his nucleus.

“The night we came through, we went up and watched his newscast and critiqued it for him,” Rowlett recalls of his first meeting with Haag. “We weren’t very complimentary, but I think a lot of the criticisms we made were the same ones he already had in mind. I think he also was impressed that we had stood up for a journalistic principle. He hired Byron and Doug and me. and of course we are all still here.”

Channel 8’s battery of new reporters quickly stirred up controversy. Rowlett drew swarms of angry phone calls with a series on prostitution, common fare today but unheard of in Dallas in 1974. Two major grocery chains. Tom Thumb and Safeway, withdrew their advertising when Harris took samples of ground beef to a testing laboratory and came back with a series called “Germ Burgers.”

By mid-1975. Haag felt he had created the kind of news program he wanted for WFAA. But ratings showed that Dallas audiences still preferred the folksy Fort Worth-style news on Channel 5 or the flashy, happy-talk approach that was coming into its own on Channel 4. A new anchor team was the next obvious change to try. and in July of 1975. Haag asked Rowlett to give up reporting and present the news alongside Iola Johnson.

“I didn’t want to be an anchorman.” says Rowlett. “The first couple of times they asked me to do it, I turned them down. But everybody was frustrated because we felt we had the best product and it wasn’t reflected in the ratings. Finally, Byron [Harris] came to me and said, ’Tracy, take the job. If it’s go-ing to help us. we need you to do it.’ I agreed to try it. and they gave me a one-year contract for $26,000.”

Something about the chemistry of the new on-air team clicked. Within a year. Rowlett and Johnson were number one at 10 p.m. and moving up fast at 6 p.m. Only once since 1976 has WFAA been seriously challenged for the lead in late evening news. That interlude came when Marty Haag was kicked upstairs.

The move was a humanitarian response, perhaps, to a tragedy in Haag’s personal life. On March 6.1980. his wife, Lynn, was killed in downtown Dallas when a truck jumped a curb onto a busy sidewalk and struck her. Channel 8 reporters at the scene were the first to learn the identity of the accident victim.

For Haag. who has since remarried, his wife’s death brought on months of depression that left him barely able to do his job. “Everything sort of melted away.” he says. “There were days after that accident when nothing seemed important. We get excited about major news stories, but when you think about the death of an individual, all of this other stuff seems trivial.”

As Haag struggled with his grief, Belo management moved him out of the newsroom and handed him the newly created title of manager for programming and program development. His job, as it was described, was to lead the station in developing new, original programs-a talk show, perhaps, an entertainment series, a midafternoon newscast. Haag hated it.

“I felt like I had been sent to Siberia,” he recalls. “I would hear about stories developing in the newsroom, and I didn’t want to be sitting there hearing it. I wanted to be out there doing it.”

At the same lime, the news machine Haag had built functioned poorly under former executive producer John Miller, promoted to news director when Haag stepped up the ladder. “We were in open revolt,” says one reporter. “It wasn’t that there was anything wrong with Miller. It was just that we all came to Channel 8 to work for Marty Haag, and we didn’t want to work for anybody else. We started missing stories and losing our edge. It really hurt us when Haag wasn’t there every day to yell at us.”

Haag was back as news director in less than a year. But nearly twelve more months elapsed before the WFAA newsroom returned to business as usual. Meanwhile, a strong anchor team at Channel 4 closed the ratings gap. In late 1982 and early 1983, Channel 8 fell to second place in Dallas.

“We did it with bells and whistles.” says Hansen, who was Channel 4’s sports anchor when that station led the ratings. “We hyped the whole show around the anchors and personalities and the fun we could have on the air. But I don’t think there ever was any commitment at Channel 4 to cover news and sports the way they are covered at Channel 8. I don’t think any of us who were there would look back and say it was a real good newscast.”

The very fact that Channel 4 could take the lead, however briefly, proved to any doubters at WFAA that the soul of Channel 8 News was Marty Haag. Says Hansen, “We survived when [former sports anchor] Verne Lundquist left Channel 8 to go to the network [in 1983). We survived when Iola Johnson left [in 1985], The only person this newscast has not been able to get along without is Marty Haag.”

•••

If it seems that most of your neighbors equate “the news” solely with Channel 8, that’s no illusion. They do. In ratings and share points, the numbers broadcasters live and die by. WFAA frequently scores higher than the city’s other two TV news operations put together. At 10 p.m., when more people in Dallas watch news than at any other time, Channel 8 routinely reaches 19 percent of all households in the Metroplex (the rating) and 33 percent of the homes in which the TV is turned on (the share). Channel 5 typically logs a 12 rating, 23 share. And Channel 4 averages an 11 rating, 20 share. At 6 p.m., Channel 8’s numbers average 17 and 28 compared to 10 and 17 for Channel 5 and 7 and 13 for Channel 4.

As recently as a year ago, the 5 p.m. newscast still was a toss-up. KXAS, Channel 5, won the numbers game for the early news nearly as often as WFAA did. Channel 4, KDFW, occasionally scored in the daily ratings with the largest late-afternoon audience. Since last summer, though, Phyllis Watson and John Criswell, Channel 8’s news anchors at 5 p.m., have commanded their time slot, collecting an average 14 rating against an 8 for 5 and 6 for 4. The result is unprecedented dominance for Channel 8.

There’s a direct link between such numbers and Channel 8’s financial health. Typically, news provides 25 percent to 30 percent of a station’s revenues. In Dallas, the eighth largest market in the country, percentages sometimes run higher. Even during the Texas economic slump, advertisers clamor for exposure during and next to the news, which gives them a well-educated, affluent audience. WFAA currently collects an estimated $25 million a year from its news operation alone-not a bad margin for a department with an operating budget of perhaps $6 million.

A station’s ratings, of course, have a big effect on the dollars. Advertising agency media buyers look carefully at A.C. Nielsen and ARB (American Research Bureau) numbers when choosing stations and negotiating rates. Ad rates in Dallas today are not as high as they were in the boom years, but a veteran Dallas media buyer says a thirty-second spot on Channel 8’s 10 p.m. newscast still goes for roughly $3,500. On the station rated third, the same spot may cost as little as $1,200. With up to sixteen spots crammed into a half hour of news, ratings points can mean big bucks.

On the other hand, though, a lower-rated station can sometimes operate more profitably than a popular one. The equipment and reporting talent essential to a quality newscast can be expensive. And the anchors, weathercasters, and sports commentators on top shows can earn up to $200,000 a year more than their counterparts on weaker channels. Still. Channel 8 remains committed to excellence at almost any price. Despite layoffs that have trimmed the news department from a high of about 120 employees to roughly 90 today, and despite a current wage freeze and restrictions on hiring, staffers unanimously agree that A.H. Belo Corp., which owns both WFAA and The Dallas Morning News, takes pride in the product as well as the profit

•••

Byron Harris calls the WFAA newsroom “The Submarine” because it is staffed by a tight knot of people working closely together under intense pressure. The reporters, photographers, tape editors, producers, news managers, and engineers are the embattled crew. Marty Haag is the mad Captain Nemo, with a little Ahab thrown in.I couldn’t even tell you where Tracy or Troy or John Criswell lives,” says Dale Hansen. “This is not a very friendly place to work.”

And in Harris’s metaphor, the newscast is the giant squid, the monster that must be fed. Five o’clock comes every day, and when that moment chimes it is feeding time. By then, the day’s stories must be covered and the scripts edited. Hundreds of feet of videotape must be cut into ten-second bites and slotted into the show. Producers and directors must have each segment timed to the second.

If all goes as planned, viewers watch a fast-paced, seamless program made up of roughly fourteen minutes of news-usually about six comprehensive stories and a flurry of headlines-followed by three minutes of weather and five minutes of sports. Yes, and eight minutes of commercials. Putting it all together, melding the vagaries of journalism with the relentless demands of technology in such a way as to satisfy audiences and win ratings, is an incredible feat.

And the monster must be fed again at 6 and 10 p.m.

“There is a lot of mental stress.” says Harris. “This is very difficult work, very tiring psychologically. As a reporter, you’re always at the needle point of controversy. And there’s no other business in the world where you get a rating every day-not just at 10:00. but at 10:07 and 10:15. We know almost instantly whether we have succeeded or failed.”

News anchor Tracy Rowlett agrees the pressure is intense at every level in the newsroom. But Rowlett says it weighs especially heavy on those who appear each night on the air. “As many newscasts as I’ve done, I don’t really think about the tension, but it’s there. Sometimes it just snaps and you come pretty close to losing it. I remember one night John Criswell mispronounced a word and I snapped and started laughing. I laughed so hard I actually fell over backward, off the anchor platform. When something like that happens, you realize how much pressure really gets you.”

Haag does not talk of the suicides of Jan Bridgman and Jack Kendrick except to remark vaguely that “I think there are a lot of factors that contribute to something like that. I think in those cases there were things in the individual’s personal life that contributed to the decision to commit suicide.” He adds, “I’m told that, statistically, you’re going to have a certain number of tragedies in any group of a hundred people.”

That said, Marty Haag defends his modus operandi, “creative tension.” He wants reporters to compete against each other. He wants anchors to know that they can be replaced. Nobody should settle, fat and happy, into the job. Nobody should feel too secure. Each employee must prove his mettle day after day after day. “I don’t think it’s injurious,” says Haag. “I think it is part of the reason we have the best newscast in Dallas.”

Television news is a high-tension business no matter where you go. but those at Channel 8 who have worked at other stations or at networks say Haag turns the boiler up several notches above what they have seen elsewhere. His enormous expectations, his unforgiving manner, his volcanic rages create a continuous condition that borders on panic. No one feels safe. Few see themselves as adequate.

“We have people come through all the time who are just miserable here,” says Dale Hansen. “A lot of them are very talented people, and they would be perfectly happy at a place like Channel 4. But they can’t take the pace. They can’t live up to what Marty expects of them. I’ve been here five years, and I’m still having to get used to it.”

Steve Price, who won four Katie awards for tape editing excellence in a recent Dallas Press Club competition, says many WFAA editors have found themselves consumed by the giant squid. In a narrow hall of editing rooms that Price calls “The Trench.” the hours before a newscast are almost unbearable, he says. “You have reporters and producers jammed in there screaming at you and threatening you. You’re trying to put together a piece of tape that will look good and tell a story on the air, and they’re treating you like you’re just a button pusher. Everybody is in a panic because they have to get the show on and it has to be good.”

Adds Price, “Most people can’t live like that. I’ve been doing it four years, but I don’t think I can do it much longer.”

Harris believes that the pressure inside Captain Haag’s submarine is at least part of the explanation for a kind of institutional coldness that pervades the Channel 8 newsroom. People who work so closely under such tension, he says, aren’t likely to be close friends. Whatever the reason, a visitor to the WFAA newsroom can’t help but notice that no one seems to have a good time. There is little idle chatter, no joking at the water cooler. People pass in the halls without nodding or speaking. They converse mostly by memo-Haag’s are known as “Nasty-grams’-and their notes are terse and businesslike.

“1 doubt I’ve had three conversations with Doug Fox or John Miller in the five years I have been here,” says Hansen. “I get memos from them and I send my memos back. I talk to the people who work for me in sports, but I barely know most of the other people here, and I’m a very gregarious guy.”

“All that stuff you see in the promotional spots, where everybody seems to be friends and they’re all having a good time, is just hype.” says Steve Price. “I put those tapes together and I know that it really isn’t like that at all.”

According to Hansen. even the four anchors who sit side by side to present the news may be hardly more than acquaintances off the set. Tracy Rowlett and weather anchor Troy Dungan are firm friends, but Hansen says he has never hefted a beer or bumped elbows at dinner with any of his three co-anchors.

“When I worked at Channel 4. we were all good friends.” Hansen says. “We used to get together after work or have dinner at each other’s houses. But I couldn’t even tell you where Tracy or Troy or John Criswell live. People here might be surprised that I would say this-I don’t think they even realize it- but this is not a very friendly place to work.”

Haag’s style contributes to the sense of isolation in the newsroom, most staffers agree. When he is not screaming, the news director is totally aloof, they say. Several reporters claim they have spoken with him only when being chewed out for some mistake. Former consumer reporter Chris Thomas claims she never heard Haag utter a single word during her last year on the staff. “He has the people skills of a woolly mammoth,” Thomas says.

Haag concedes that he is not the great communicator, that he does demand extraordinary quality and quantity from his employees, that he rarely commends a staffer or hands out congratulations on a job well done. But his answer to such criticism is that the newscast speaks for itself. His job is to put on the finest show he can and win the best ratings. That’s all. If people need coddling, they’ve come to the wrong place.

Haag adds only that he tries to restrain himself, that he is not as volatile as he once was. “I’m an excitable person. There’s something that clicks in me when a big story breaks. I’ve tried to control myself over the years, to contain myself. There used to be a lot more yelling and screaming than there is now. People here now understand my philosophy. They know what I expect.”

•••

I wouldn’t stay at Channel 8 IF Marty Haag were not the news director.” says consumer reporter Bonnie Behrend. “I just can’t imagine working in this market if I had to work for anybody else.”

Behrend’s sentiment is a common one. Despite the pressure, despite the alternating moods of chilliness and fury, those who endure beyond the first few weeks harbor deep affection for their news director. “It’s almost like being a teenager at a dance and there’s one boy who won’t pay any attention to you,” says Chris Thomas. “You really want that particular boy to like you. You are willing to do almost anything just to have him notice you. That’s the way everybody feels about Marty Haag.”

“The fact that you have so many people who have been here for years speaks for itself.” says reporter Brad Watson, who joined 8 in 1979. “I don’t think anybody would want to see Marty Haag leave this job.”

One of the questions that arises repeatedly in conversations with Channel 8 staffers is whether Channel 8 News could survive without Haag’s driving energy. Could the newscasts still be as good as they are? Could Channel 8 continue to dominate the ratings, or would it drop back to join the pack?

General manager Dave Lane and Haag both insist that the organization today is solidly built and could endure no matter who sits in the news director’s tiny office. “If Marty Haag leaves tomorrow, he’ll be missed,” says Lane. “But he has put the mechanism in place and I think it could do just fine without him. I have a bunch of thoughts about who might replace Marty, but I’m not going to talk about them because it isn’t time.”

In fact, within the Channel 8 newsroom, growing speculation says it is time, or almost. Many staffers believe Haag is at the verge of a promotion that will put him in the executive offices to oversee news at all Belo stations. It is the only way to solve an embarrassing problem, several reporters believe.

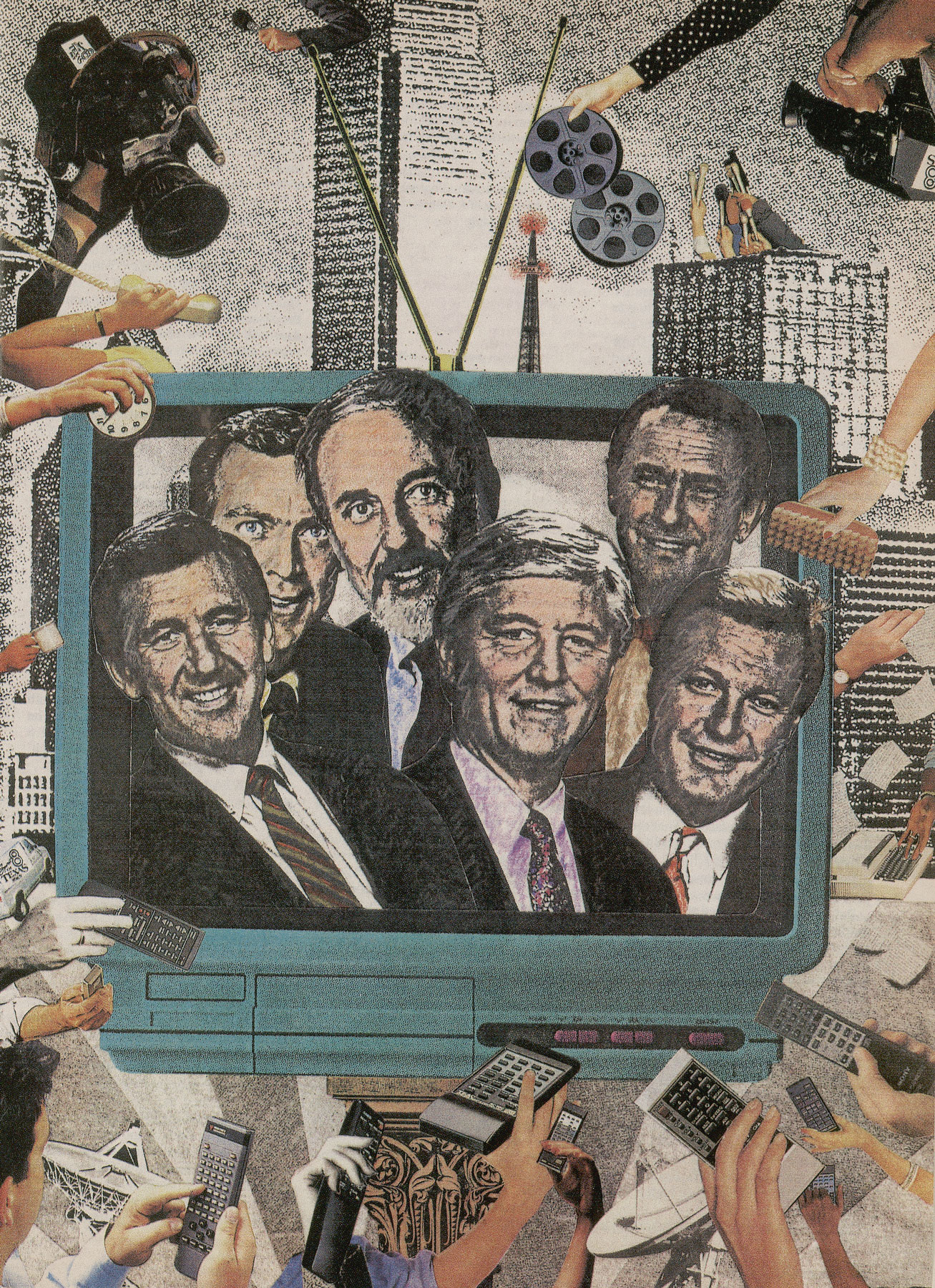

The problem is the anchor lineup that many staffers, especially the women, refer to as “Four Middle-Aged White Guys Sitting Around Talking.” It is the fact that the anchors who present the news at 10 p.m., the high-visibility hour, are all white males. Chip Moody, Tracy Rowlett, Troy Dungan, and Dale Hansen. Add John Criswell, who shares anchor duties at 5 and 6 p.m., and you get as WASPish a group of graying dandies as you ever want to see.

Minority groups have protested the anchor lineup since September ], when WFAA bumped Midge Hill from her anchor job to make room for Moody. Columnists in both Dallas newspapers have wondered whatever happened to social responsibility at the station that influences more viewers than any other in Dallas. Women in the newsroom have fumed that Channel 8 has increasingly become a good ol’ boys club. Tracy Rowlett has quietly met with Haag and Lane to express his concern about the scarce visibility of women and blacks on the air.

Even Lane and Haag. who jointly decided to switch to the current lineup, say they are not entirely comfortable with it. Both say they would prefer to see women, blacks, and Hispanics at their anchor desk. But they insist that research shows the current lineup is the strongest in audience approval.

“This is a business and we have to run it like a business and put the strongest team we can on the air,” says Lane. “Yes, we have a terrific social responsibility. And yes, we do recognize that this lineup is a problem.”

How to solve the problem? Exit Marty Haag as news director, says one theory. Replace him with Tracy Rowlett and open an anchor job for a female, a black, or a Hispanic. This is the scenario going around the newsroom, and it makes a certain kind of sense. The trouble is, it is a solution that begs the question. Rowlett is an essential ingredient in the current, overpowering anchor team.

According to Lane, research shows Rowlett and Moody are neck and neck for number one in audience acceptance among news anchors in Dallas, John Criswell and Channel 4’s Clarice Tinsley also are roughly tied but down a notch or two. All others herd together well back of the leaders. Of those two frontrunners, Rowlett is the one with demonstrated staying power. Moody, a recovering cancer victim and a former anchor at both 4 and 5, is the surprise.

“We hired Chip [from Belo’s Houston station] knowing he had cancer and not knowing how well he would ever be,” says Lane. “We looked at his tapes and found he was good but not as good as he used to be. But he wanted to come back to Dallas, and we said we would try him on weekends.

“Four months later, we did a research study showing he was having an effect. Another project this spring showed he was right up there with Tracy. As long as Chip’s health remains good, we think he will continue to do well in this market. But we certainly aren’t going to put all of our eggs in that basket. Tracy has been a leader for a long time.”

Rowlett says he would like to open opportunities for women and minorities, perhaps by increasing the number of anchors on the air. But he scoffs at the idea that he is about to replace Marty Haag. “When I reach the place where I’m no longer the best person to have on the air-and it will happen-I’m not sure 1 want to go into management,” says Rowlett. “I might prefer to go back on the street as a reporter.”

For Channel 8, the anchor lineup is a dilemma of social responsibility warring with business acumen. It is damned if you do change-and risk losing audience share with a less effective team. It is damned if you don’t-and risk alienating blacks. Hispanics, and women. Lane hints that changes will come within the year. Chances are, though, Marty Haag will not be replaced.

“I will not accept a position that does not allow me to be a part of this newsroom,” Haag states vehemently. “You can safely say that I’m not going anywhere.”

With that, the conversation is closed, so far as Haag is concerned. For the next ten years, until he reaches sixty-five, the newsroom will be his. There is no reason to wonder whether Channel 8 News can survive without Marty Haag. Anchors and reporters may come and go. The news team may grow to accommodate a woman or a minority. Ratings may fluctuate. But The Mountain will not move.

The Haag has spoken.