We all know the helpless, furious feeling-the ultimate frustration of haggling with the guy who supposedly fixed a faulty transmission or a broken down air conditioner. Stranded in your useless car on the way to that all-important business appointment, or sitting in the 110-degree heat in your house, you wonder… has the schmuck already cashed the check you wrote for the repairs? You write the president of the company, spend endless hours on the telephone, scream at the repairman, the person who answers his phone, your spouse, your secretary, and any dog or cat that gets in your way. When you meet a dead end at every turn, who ya gonna call?

We were the people on the other end of the phone line when you really needed to holler. Combined, we’ve spent fourteen years in the field of consumer protection as teacher, journalist, or administrator. When we started the Contact 8 hotline for WFAA-TV in Dallas in 1981, consumerism was a trendy, gutsy, hard-charging pursuit. Ralph Nader’s Raiders may have begun the march, but we beat the drum on a local level, training volunteers, developing form letters and complaint-handling procedures.

But as memories of Seventies consumer activists faded, our follow-up talks with consumers revealed an interesting and discouraging trend: nothing was happening. Complainants who took the time to fill out all the “official forms’-even ours-got few, if any, results.

Consumer agencies across the nation have fallen on hard times, both philosophically and financially. And so, it follows, have consumers. Dallas can even be called a trendsetter in this regard. After all, this city has long been known for its pro-business climate where, some think, the little guy’s rights are trampled-or at least ignored-in the pursuit of progress. The skepticism about Big Business fostered by Nader and his devotees never really caught on here, even in its heyday of the Seventies.

Today, during the Reagan administration, the caveat emptor trend has gathered enough strength to become a full-fledged national goal: cut spending, let the watchdog agencies atrophy, and the marketplace will right its own wrongs without Uncle Sam’s intervention. Consumers are supposed to be able to take care of themselves in 1986, and if they get ripped off, it’s because they weren’t savvy enough to prevent it. Better luck next time, sucker.

We can understand that philosophy. We’ve seen some amazingly dumb consumers. But we have also seen hundreds of intelligent, articulate folks reduced to quivering heaps of frustration, strangled by red tape that defies reasonable explanation. They are people who don’t even think about consumer groups or laws or rights. . .until they have a problem. Then they notice how little help they get from the organizations they had assumed could assist them.

In Dallas, the number of citizen complaints is at an all-time high, while consumer agency staffs dwindle and state and federal funding is curtailed. So, right this minute, your car or apartment or insurance complaint may be stacked on somebody’s desk; it’s not a priority anymore. When we were at Contact 8, we compiled a file of more than 350 organizations, groups, and agencies whose mission, like ours, was to resolve consumer disputes- Some of those groups are gone now, others aren’t as effective as they once were. Following is a rundown on what’s left for the frustrated consumers in the Dallas area. Here’s who you can call. . . .

STILL CHUGGING

THERE ARE SOME ORGANIZATIONS WHERE TOUR INDI-vidual complaint is still a priority. Crises seem to be a normal part of life at the Dallas Tenants’ Association. After all, more than half of the heads of households in Dallas are renters. If they each paid the fifteen-dollar membership fee to join the DTA, even if they were personally inactive in the organization, the group might have the funds to become a powerful consumer force. In reality, people only join when they have a problem,so membership fees comprise only half of the DTA’s budget. The rest comes from church groups and charitable organizations.

Unlike most state and federal agencies, nonprofit organizations like the DTA have long been accustomed to operating on a shoestring. Still, the lagging economy is forcing the DTA to compete with other housing foundations for dwindling donation dollars. “As a renters’ group, we face a distinct handicap,” Dorothy Mas-terson, DTA administrator, says. “People who have lots of money are landlords-or at least they have friends who are landlords.”

DTA program director Gayle Cooper says the association gets 125 telephone inquiries per day. The biggest complaint category is lack of repairs; eviction is second. Although retaliatory eviction-kicking people out of their apartments for complaining about conditions-is illegal, it does happen. But even if you don’t pay your rent, you can’t legally be evicted without a court hearing. So when renters get their ominous notification to appear in court, they call the ETTA in a panic.

The rules are less clear in the broad complaint category known as “habitability,” which includes everything from roach infestation to plumbing problems to lack of heating or air conditioning. Texas law requires that renters complain in writing about their apartment problems, then allow the building owner and manager “reasonable time” to make repairs. Still no repairs? Write another letter, the law dictates, and give the landlord seven days to do the work. If that doesn’t do the trick, though, a tenant’s only right is to break the lease and move, supposedly without being penalized.

A lot of people ask the logical question: can I withhold my rent money for the days I went without (fill in the blank) air conditioning, hot water, electricity, etc.? The answer is-emphatically-no.

All this considered, it’s not surprising that the DTA suggests renters with habitability problems band together to give additional clout to their complaints. This can be a real turnoff for the tenant who is expecting individual help and is instead advised to start drafting petitions, recruiting neighbors, and holding meetings.

If you do have persistent problems with your rental digs, and you’re not sure where to take them, you might just sit in on one of the DTA’s workshops (attorneys and counselors are there to answer questions) held the first Monday of every month at 7:30 p.m. at Iglesia Bautista, 212 South Beckley Avenue; every Wednesday at 6 p.m. at the Oak Lawn United Methodist Church, 3014 Oak Lawn Avenue; and Saturdays at 10:30 a.m. at the Brady Center, 4009 Elm Street. Attending a workshop is easier than trying to get through on the DTA’s phone lines, which are almost always busy. If you want to call, the number is 828-4244.

EVERYONE KNOWS THEY’RE SUPPOSED TO CALL THE Better Business Bureau and check on a company’s record before making a business transaction, especially one involving a lot of money. But very few people know exactly what they’re supposed to get from the call.

Say someone has a question about the reputation of XYZ Swimming Pool Builder. “The company has been in business for two years,” the BBB employee on the phone will answer. “In the past year, we have had one or more unresolved complaints against XYZ.” Then the employee will launch into a prepared statement about the information being “neither a condemnation nor an endorsement” of the business and offer to send the inquirer a pamphlet about pool builders.

Great. What in the hell does that mean? Is it one “unresolved” complaint, or ten? Are they good guys or bad guys? To avoid lawsuits, the BBB has chosen very carefully the terms of its telephone reports, and that can be frustrating to someone who’s calling for free advice. But the Dallas BBB is responding to such complaints by disclosing the exact number of complaints in two select categories: swimming pool builders and “prize letter” companies that offer boats, cars, and cash to lure potential customers to their sales presentations.

The BBB’s annual number of requests for reports on companies topped 100,000 in 1985. The BBB also gets more than 13,000 complaints per year, both by telephone and letter. The bureau wants complaints in writing (they furnish the form), an annoyance to complainants who feel they need more individual attention or more specific advice than the array of “buying tips” contained in the BBB pamphlets.

When complaints are filed, the BBB simply sends a copy to the business and asks for comments. For people who have already made their wishes clear to the business without results, this is not a particularly satisfying system.

Wounded consumers with more complex cases are better off requesting an arbitration hearing in the BBB’s Customer Care Program. Businesses that pay to join Customer Care pledge to arbitrate their disputes with a volunteer third party who listens to both sides and renders a decision that is legally binding on both the consumer and the business. The Dallas BBB handles about 2,500 arbitrations per year.

In the last two months, there has been another reason to call the BBB-to obtain information about charitable solicitations. The bureau has formulated standards for charitable fundraising and has rated charities according to its own stringent set of guidelines. The new program, called the Philanthropic Advisory Service, is a direct result of the federal budget crunch that has prompted a big increase in charitable fundraising in the private sector.

There are 4,000 members in the Metropolitan Dallas BBB. It is the only organization we surveyed that reports a staff increase over the past five years-from eighteen to thirty-two employees. The bureau has moved to new quarters, doubling the size of its previous space, and has computerized its 13,000 company files.

Its critics say that just because members pay dues and display a BBB membership plaque in their office does not mean they are fair or honest, and that’s true. But in the vast majority of cases, membership in the BBB does indicate a willingness to work out problems in a prompt, reasonable fashion.

You can call the BBB at 220-2000 to request an official complaint form.

OUR GOAL IS TO WORK TOWARD a more peaceful community. If people would just sit down and talk, and listen, and deal with each other like human be-ings. . .” It sounds like something out of the Woodstock era, but it’s a quote from Herb Cooke, executive director of the Dispute Mediation Service of Dallas. And it isn’t as naive a statement as you might imagine.

Of all the consumer agencies we’ve surveyed, Dispute Mediation boasts the highest complaint resolution level-a staggering 90 percent. What’s even more amazing is this: the group is endowed with no enforcement power. Cynics may scoff, but Dispute Mediation relies on such antiquated concepts as ethics, reason, and common sense to bring two angry sides to agreement.

Dispute Mediation has sixty-two local caseworkers who have had forty hours of mediation training and made a one-year commitment to the organization. They are matched as closely as possible with cases pertaining to their interests and backgrounds. An attorney might mediate a landlord-tenant dispute, for example. Either party can withdraw from mediation at any time, but if they stay for a decision, they are asked to sign a written agreement called a “memorandum of understanding,” which is just as valid in court as any other kind of contract. There are no hard and fast rules about repayment in a dispute mediation; individual circumstances dictate the terms of each contract.

The whole idea, of course, is to avoid the time, expense, and hassle of going to court in the first place. Dispute Mediation Service is handling a steadily increasing number of divorce arrangements, working out child support and property considerations that reduce the expense and acrimony of divorce cases.

Another growing caseload area is juvenile restitution. A teenager accused of vandalism, for instance, can sit down with his parents and the victim and work out a pay-back plan to make up for the damage. Kids who don’t live up to their mediation agreements go right back where they started-juvenile court.

It takes several days to set up a mediation session, and the organization strives for a ten-day turnaround in most cases. In the first six months of its fiscal year (October ’85 to March ’86), Dispute Mediation Service accepted 903 cases and took action on 662 of them. There’s a five-dollar fee to take the case and another five-dollar fee for the mediation, although some cases involve additional costs that are determined on a sliding scale.

You can call Dispute Mediation Service at 821-4380.

IN APRIL, A MAN FROM MT. PLEASANT, TEXAS, WROTE TO the Texas State Board of Insurance complaining that a medical claim he filed with his insurance company in January still had not been paid. First, the company told him it was _ waiting for medical history information from his physician. Then his file was misplaced. All along, his insurance agent seemed to be avoiding his calls. On April 11, the State Board of Insurance sent an inquiry letter to the insurance company. On April 15, the customer received a written apology from the company and a bank draft for $4,097.

Results: what more could you ask from an agency? But perhaps that particular story is deceptively simple. After all, there are 193,293 current insurance licenses for agents and adjusters issued in Texas, and the total number of telephone inquiries to the state board topped 60,000 last year, up from 40,000 in 1984.

Unlike so many groups and agencies charged with consumer protection, the State Board of Insurance has some power to wield. It not only sets the rates for car, homeowner, and workers’ compensation coverage, it licenses agents and companies in Texas. It also approves the wording of each of its policies, which, since September 1984, has included information about how to contact the State Board of Insurance with any unresolved complaints.

To paraphrase an even more powerful entity, “What the board giveth, the board taketh away”-that is, its disciplinary powers include the ability to put agents or companies on probation or to suspend their licenses altogether.

However, the latest figures don’t sound encouraging for those consumers with serious insurance problems, like fraud. In 1985, the state board held 109 hearings. Licenses were revoked in sixteen cases; in seventy-eight more, fines were levied. The most common violation occurred when agents collected insurance premiums and pocketed them instead of turning them in to their companies. The board recovered $10.7 million for consumers in 1985, which represents a decrease from the previous year.

The state board has eighteen insurance complaint investigators, all based in Austin, but eight of them travel statewide. “The board is asking for a 41 percent increase in budget,” says Lee Jones, assistant director of research and information services. State budget woes make it highly unlikely that this request will be granted.

While the State Board of Insurance can’t promise everyone the same four-day turnaround that it managed for the Mt. Pleasant man, it has installed more lines on its toll-free phone system to handle the recent increase in complaints.

For better results, write the State Board of Insurance at 1110 San Jacinto, Austin. Texas 78786, or call toll-free at 800-252-3439.

MORE BARK THAN BITE

IN THE PAST FIVE YEARS, THERE HAVE BEEN TWO MAJOR reorganizations of the City of Dallas Department of Consumer Services that have fragmented the department and reduced its effectiveness. At the beginning of this decade, it was called the Department of Consumer Affairs. It was a high-I profile, highly media-conscious entity. It had two part-time public relations staffers who made radio and television appearances, wrote news releases, and kept the department in the public eye so that citizens who had problems would know where to call. And when they did call, citizens spoke to consumer specialists, the people who actually investigated cases in areas where the city has jurisdiction, such as auto and home repair, door-to-door sales, or charitable solicitations.

But in 1981, the department was combined with the city’s public utilities department. The folks in this department regulate utility rates, set fees for cable television, inspect taxicabs, license wrecker services and ambulances, and regulate the bus and limo service at D/FW airport. As you might imagine, all these “specialties” under one roof make for some consumer confusion. These additional responsibilities were heaped on the city’s telephone bank, the Action Center, which formerly handled only those complaints related to city services: trash pickup, weed mowing, traffic improvement requests….

For the cases that find their way into the hands of the consumer specialists, though, the department boasts results. Since October 1985, the start of the city’s fiscal year, Consumer Services logged 3,677 complaints in a six-month period, recovering a total of $441,000 in damages-half of them in the category of home repairs, More than 600 merchants were either ticketed or prosecuted for violating city ordinances.

This year, expected city budget cuts will necessitate yet another sweeping reorganization of Consumer Services. The Dallas City Council will vote on the new, leaner budget by September 30. Some people have lost their jobs as the department’s various functions are parceled out.

If the City of Dallas continues to de-emphasize its consumer advocacy function, it will be a reflection of both the conservative business climate and the need to trim expenses. But you can still call the Action Center at 670-4014.

A STRATEGICALLY PLACED REPORTER WITH PAD, PENCIL, or camera can often make more headway on a consumer complaint than a lawyer, an agency, or a shotgun. In the mid-Seventies, newspapers and television sta-tions began to realize the good will they could generate by offering problem-solving services that got right to the heart of readers’ and viewers’ daily concerns. Particularly on television, this made for some dramatic moments-videotaped confrontations, close-ups of filth and shoddy workmanship, tearful consumers clutching their violated contracts. On today’s local newscasts, consumer journalism is a muted voice. The change can be attributed to high-paid media consultants whose constant search for trendier topics and bigger ratings has led us in recent years through the age of “reporter involvement” (when reporters jumped out of airplanes or worked as short-order cooks for a day and then aired their cute and clever observations); to the days of “consumer advocacy” (when reporters tried to lure audiences to the stations that were “on the consumer’s side”); and most recently to the world of “health news” (now the reporters aren’t reporters at all, but TV doctors passing out free medical advice).

Gone are the days of Channel 5’s consumer investigator Jack Helsell, whose hard-charging approach has been replaced by the sunny Money Desk 5, a friendly, newsy consumer segment anchored for the past two years by Tim Smith. Money Desk doesn’t solve consumer complaints at all; it offers helpful hints.

Channel 4 once featured In Your Corner. Reporter Chris Houston (and later, Denise Tichener) would investigate call-in complaints with the help of a full-time assistant. Regular consumer segments haven’t been on the air at Channel 4 in three years.

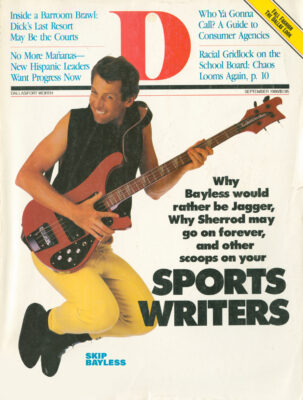

Channel 8 launched a consumer offensive in 1981 with Contact 8, a telephone hotline agency with two full-time staff members, two full-time reporters, and twenty-four volunteers. Reports were aired five to six times a week. Today, Contact 8 has one full-time staffer and seventeen volunteers.

As for print media, this magazine has done sporadic consumer pieces and occasional cover stories devoted to helping buyers beware (see “How to Complain,” May 1984) but has no regular department for consumer affairs. The Dallas dailies have also scaled down their consumer complaint operations. In the early Eighties, the Dallas Times Herald featured a full Consumer Rage, edited by Martha Smith. Today, only a fragment of that idea remains in the Action Line column. And at The Dallas Morning News, a four-person staff has been cut to two. Its Line One column, which began in 1979 and was originally a front-page feature, has long since been relegated to the Today section’s Inside Page, just north of the horoscopes and east of the Ann Landers column.

Like its electronic counterpart, print media is also trend conscious. And consumer-advocate reporters walk a tightrope between helping complainants and angering advertisers. Yet in this very competitive media town, consumer calls still prompt stories, and sometimes get results. You can call Contact 8 at 988-9898; Action Line at 720-6250; Line One at 977-8237.

WHEN STUDENTS AT THE UNTVER-sity of Texas at Arlington have housing or repair problems, legal adviser Shayla Freeman is hesitant to send them to Small Claims Court. “In my experience,” she explains, “few of them are happy with the results.” Each J. P. in the Dallas area hears more than 6,000 cases per year, so if you file a small claims case, expect to wait at least two months to get into the courtroom.

Much of their disillusionment is probably due to the biggest misconception about “the people’s court”-you can’t just walk in, tell your story, and win. A disagreement involving $1,000 or less is considered to be a “small claim” in Texas. The court procedure is supposed to be relatively informal and more streamlined than in the higher courts. Both parties usually represent themselves instead of hiring attorneys. The most difficult cases, says Justice of the Peace Jack Richburg, are those in which the consumer comes in alone and the business brings a lawyer.

Some people are relieved, no doubt, when the person they are suing doesn’t even show up in court. After all, that means the plaintiff automatically wins. Then, the real fun begins for the winner-trying to collect on a judgment.

“You’d think the situation would be cut and dried,” says Ross Bracey, “but it isn’t.” Bracey and his fellow constables go out and collect the winnings, after the winners buy a forty-two-dollar writ of execution that is required before constables can collect. He estimates that businesses refuse to pay about 40 percent of the time while individuals don’t pay 90 percent of the time.

Richburg adds that most people overlook an additional remedy, called the abstract of judgment. It works this way: if you win a small claims case, you must wait ten days to allow the defendant to appeal. If no appeal is made, you pay the court one dollar to get an abstract of judgment, which costs another three dollars to be filed with the county clerk’s office. Then you wait. The abstract has the same effect as a dispute on a credit record; big problems for the defendant if he tries to buy or sell “real property” like his house or car. The transaction cannot legally take place unless the abstract of judgment is cleared up, assuring you of getting your money sooner or later-or at least causing your defendant a lot of inconvenience for the seven years during which the abstract is binding.

Small claims cases are filed by precinct. Call 749-8591 to find out which precinct you’re in and how to file.

ON THE SURFACE, IT APPEARS AS though the Attorney General’s Consumer Protection Division has suffered some setbacks. After all, Jim Mattox’s last request for a hefty budget increase was met with a 7 percent decrease by an unwavering state Legislature.

But there’s good news as well: finally, the state is getting some veteran consumer attorneys for its money in the Dallas office, which serves the entire northern half of the state. There are only two attorneys, but they are filing more cases than a trio of predecessors. The frustration in the AG’s office is articulated by attorney Steve Gardner: “Everyone is looking to us to sue on an extremely limited budget.”

The AG’s objective in filing a lawsuit may surprise some. The objective is not to get money back for victims, but to put the masterminds of the scam out of business and keep them from harming anyone else.

If it’s a cash settlement you want, you’d be better off requesting mediation from the AG’s office. Two consumer analysts wade into the middle of disputes, either by letter, by telephone, or in person. But mediation is hampered by the more than 7,000 calls per month to the Dallas attorney general’s consumer protection office of ten staff members. In any given month, the office is engaged in about fifty active lawsuits. The mediation service is free, and the statistics show that there is a fifty-fifty split between those satisfied and those dissatisfied with the outcome of their cases.

You can call the Texas Attorney General’s office at 263-2685 for a complaint form.

CHARLIE MITCHELL SUMS UP THE reason that most people contact the District Attorney’s Consumer Fraud Section: “They think it’s fraud any time they lose money or they don’t get what they paid for.” Mitchell is chief of the consumer fraud section, which gets so many inquiries that a form letter has been drafted to explain the fine legal line between “fraud” and “business failure.” It reads, in part: “We must be able to prove that, at the time the contract was made, the accused never intended to perform, and in fact intended from the outset to steal the victim’s money.. ..”

Investigators in the D.A.’s office are seeing more and more cases of bad business judgment or bad economic conditions cited as the reasons jobs aren’t finished. These are stories, but they’re not crimes.

However, the office will investigate if incoming calls point to a pattern of questionable sales pitches. Criminal intent is proven by producing a string of victims who have all fallen for the same slick promises. The consumer fraud section is part of a larger division called Specialized Crime Division. Its eight attorneys and eleven investigators also handle complaints in the areas of commercial fraud (embezzlement, stock and investment fraud, land fraud); public integrity (bribery, corruption, election fraud, Medicaid/Medicare fraud); and organized crime. There are 900 pending investigations and cases, and new calls come in at the rate of 400 per month. Callers are asked to put their complaints in writing.

If you really think you’ve got a criminal or your hands, and you don’t think you’re the only one who has been taken, send a letter and copies of all your documentation to the D.A.’s Specialized Crime Division, Consumer Fraud Section at 2720 Stemmons Freeway, 400 South Tower, Dallas, Texas 75207.

I HAVE A THEORY,” CRAIG SANDLING laughs, “that we get all the good stuff nc other agency wants.” Sandling, a staff attorney for the Texas Department of Labor and Standards, refers to the I mishmash of responsibilities entrusted to his department: mobile home complaints, licensing boxers and wrestlers, registering health spas, inspecting privately owned storage lots, and so on.

Somewhere in that grab bag is a labor division charged with investigating complaints about nonpayment of wages. Fifteen investigators travel the state working complaint resolutions, but it’s an uphill battle. Statewide, there were 11,000 complaints during the division’s fiscal 1985. Complaints are up this year; the labor division is seeing more bankrupt companies and more complaints from both oil-related industries and construction subcontractors who haven’t been paid or whose paychecks have bounced. And it’s happening at a time when the state cannot afford to hire more labor department employees. The law doesn’t force employers to pay back wages, so the investigators try to negotiate a voluntary settlement on behalf of complainants.

You can write the Texas Department of Labor at 5925 Maple Avenue, Dallas, Texas 75235.

“UNDERSTAFFED, UNDERFUNDED, UNDER REAGAN”

AS ONE LOCAL CONSUMER PROTEC-tion attorney describes the federal agencies, “They’re understaffed, underfunded, under Reagan.” An-other common thread: their func-tions are very specific and are often misunderstood. While the Texas Department of Labor & Standards handles nonpayment of wages, the U. S. Department of Labor handles consumer questions and complaints about minimum wage and overtime violations.

Assistant Area Director Brian Farrington says the law does not even mention things like vacation pay, holidays, or lunch and coffee breaks. Those are traditions, not requirements, and cannot be enforced by the feds. Likewise with layoffs and firings.

“In Texas,” says Labor Department Public Affairs Specialist Lynn Ligon, “it’s a kind-of ’employment at will’ situation. You can be hired and fired for any reason except discrimination.” File discrimination complaints at the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, unless they involve a federal contractor, then trudge right back over to the U. S. Department of Labor and ask for the Office of Federal Contract Compliance Programs.

The labor department doesn’t have the authority to seize your boss’s bank account or property to force a payback, but it can take employers to court.

You can write the United States Department of Labor at 525 Griffin, Dallas, Texas 75202.

AS DALLAS AREA CONSUMER AGEN-cies go, the US. Consumer Product Safety Commission has a low profile. Every year, one of its em-ployees makes the rounds of local radio and television stations and answers a few questions about Christmas toy safety, and that’s about it, many think.

In fact, the CPSC has wide-ranging jurisdiction over the safety of approximately 15,000 types of products. Setting priorities, as you might imagine, is quite a challenge. The agency wants to hear from you if you think a product is hazardous, or if it has actually caused an injury. Your complaint, however, will not necessarily spur an investigation. Many people are under the mistaken impression that the CPSC is the agency that tests toys to determine whether they’re safe before they go on sale to the public. Instead, only a random amount of sampling is done-checking the lead content in painted toys, for instance. The CPSC doesn’t have the staff or budget for pre-market testing. It is reactive, dependent on consumer input to pinpoint hazardous products.

“One misconception people have,” says CPSC Public Affairs Specialist Stephen Vargo, “is that we’ll call the company and get their money back for them.”

Manufacturers are required to report injury cases involving their products to the CPSC, and the agency can inspect plants and negotiate terms for recalling merchandise and correcting manufacturing defects.

When the CPSC was created in 1973, there were almost 900 CPSC employees, in five regional offices. Now, there are 550. The seventeen workers in the Dallas office are known, if at all, for their inspection and investigation of malfunctioning amusement rides at the State Fair of Texas.

Currently, the CPSC is interested in public information and comments on two topics in particular. One is residential swimming pool safety. In the United States, more than 3,000 children annually have backyard swimming accidents; another 300 kids under age five drown each year in this country.

The other hot topic is the “all terrain vehicle,” the three- and four-wheelers with big balloon tires. Marketed primarily to children, an increasing number of injuries and deaths involving these vehicles prompted the CPSC to hold five hearings on the subject; one was in Dallas in June 1985. Perhaps it’s just bureaucracy that has prevented any official conclusions from being drawn, since the information is now more than a year old. Regardless, the case illustrates the reason other local agencies say they seldom refer complaint callers to the CPSC.

The Consumer Product Safety Commission can be reached at 767-0841.

WHEN THE HEADLINES ARE FULL of warnings about tainted drug capsules or glass fragments in baby food, the investigators at the U.S. Food and Drug Ad-ministration brace themselves for long hours on the phone. At such times, the fourteen investigators in the Dallas office, responsible for Texas, Oklahoma, and New Mexico, are swamped with callers asking, “Will you test my bottle and see if it’s okay?”

It’s a real test of tact for chief investigator Ted Rotto and his staffers. “We’re not a full-service laboratory for consumers,” he says, “and we’re so short-handed that unless there’s an illness or injury involved, we simply don’t have the resources to handle it.” He echoes the frustrations of other government agencies-more complaints, fewer staffers, smaller budgets.

Don’t get the wrong impression. If you find metal shards in a candy bar or bugs in some canned shrimp, it is a good idea to report it to the FDA. But if it’s immediate action and a refund that you’re looking for, you’d be better off calling the company that made the product. The primary function of the FDA is to record consumer gripes, not to solve them.

From January through June of this year, the Food and Drug Administration got 393 of what Rotto calls “bona fide complaints” in Dallas alone. That doesn’t include another 530 calls during the glass-in-baby-food scare, or the calls about poisoned Tylenol and Excedrin capsules, still rolling in. Another category of calls-amounting to as much as half of the total-are “wrong numbers.” Rotto elaborates: “We get a constant string of complaints about dirty restaurants. Those belong at the local or state health departments. Fresh meat, poultry, and eggs are covered by the U.S. Department of Agriculture. We do not administer Food Stamps-that’s also the USDA.” You can call the FDA at 767-0312.

THIS SUMMER, SPLASHY HEADLINES were made by the Federal Trade Commission when it blocked the proposed mergers of Pepsico with 7-Up, and Coca-Cola with Dr Pep-per. But those waves were made in the FTC’s Bureau of Competition, which handles big antitrust cases. By comparison, the commission’s Bureau of Consumer Protection only makes ripples in Dallas.

Several other consumer groups say they seldom refer callers to the FTC since their complaints are more likely to net informative pamphlets than actual remedies. In fact, the agency’s newsletter explains that the agency is “not authorized to resolve individual consumer complaints, but acts when it sees a pattern of abuses.” Sound familiar?

On the other hand, the agency seems most effective in the area of credit law, where it handles discrimination charges, unfair billing practices, and debt collectors who have overstepped their legal bounds.

Locally, the FTC spends a good deal of time combing ads for house and car purchases to see if they contain “triggering terms.” For instance, if a homebuilder advertises especially low finance rates, federal law requires him, in the same ad, to elaborate: what’s the down payment? What are the exact loan terms? What’s the actual annual percentage rate? The agency estimates its crackdown on credit disclosures has increased advertiser compliance from 14 percent to 86 percent.

The Dallas FTC office receives more than 400 phone calls per month and requests that you “put it in writing.” Patience is also a virtue; it’s going to take time for the FTC to get around to your complaint. You can call the FTC at 767-7050.

WHENEVER WE THINK OF THE “five-dollar emeralds,” we think of the US. Postal Inspectors. That was a case in which the adage “you get what you pay for” was never more appropriate.

The same company that was sometimes called “Abernathy & Closther,” sometimes “Carter & Van Peel” to name only a couple of its aliases, still advertises regularly in weekend newspaper supplements-five-dollar cameras, digital watches, “diamond” earrings, all available by mail. “We’ve gotten so many false representation orders on those guys,” says Postal Inspector J. R. Price, “that the U.S. Attorney is barely interested in pursuing them anymore.”

And no wonder. When you’re a postal investigator-there are eight of them working fraud cases in the Dallas-Fort Worth area-you start to think that maybe people deserve what they get (or don’t get) when they fell for gimmicky ad claims that are obvious come-ons.

As with other agencies funded by taxpayer money, the Postal Service looks for large numbers of complaints, large losses, and distinct patterns of fraud to make a convincing case. One attorney calls it the “kill ’em dead” theory: gather enough evidence to guarantee a courtroom victory for the U.S. Attorney’s office.

Unfortunately, the time involved in building such an elaborate mail fraud case meansdozens, maybe hundreds of people will bevictimized by the time charges are actuallyfiled. The Postal Inspector requires complaints in writing. You can write the UnitedStates Postal Service at P.O. Box 162929,Fort Worth, Texas 76161-2929.

The mystery of the shanghaied shutters

People moving into a new house often lack up some sheets over the windows until they decide on the right curtains, shades, or other window treatments. But the sheets were up for many months in dozens of Dallas-area homes in 1983. The homeowners were waiting for custom-made window shutters they had ordered from “Shutters by David.”

In July 1983, before Rosemary Woods of Irving made her down payment, she wanted to make sure that Shutters by David was a legitimate business, so she drove to David Kirtley’s Oak Cliff office, an old dry-cleaning shop. There was no sign out front. “It was a little hole in the wall,” she said, “but there were people in there working, and they had a stack of orders. They had to look for my order to find it, and it seemed to be a thriving little business. I wrote my check for $488 as my down payment for the shutters.”

Another customer, Dianne Young, tells a similar story. She paid almost $700 to David Kirtley and was promised her shutters in six weeks. She called weekly to check on the progress; the eleventh week she reached a recording: the phone had been disconnected. “Shutters by David” disappeared from its tiny location in September 1983. Neighbors said the move was made in a hurry. The building owner said the rent was not paid. The customers started calling consumer agencies: the Attorney General’s office, the Better Business Bureau. Contact 8. Woods and Young told their stories on the Channel 8 news on October 25, 1983, and the particulars were passed on to the Dallas County District Attorney’s Consumer Fraud Division. The leads on Kirtley’s whereabouts were sketchy-he told some customers he had just bought a house in Lancaster; others thought he lived in Duncanville.

More than a year later, he was located. Complainants still don’t know the reasons for the long delay, nor the story behind the demise of “Shutters by David”-why it foiled, where the money went. But James David Kirtley pleaded guilty to “Theft over $750,” a third-degree felony charge. On December 3,1985, he was sentenced to a two-year prison term.

Kirtley served 160 days of his sentence before being granted parole, with the requirement that he must make restitution to his former customers, an amount in excess of $19,000. One of the customers is J.W. Marshall, a Dallas man who is owed $4,000 by Kirtley. In June, Marshall received a form letter from the Board of Pardons and Paroles. The board needs Marshall’s address and social security number to mail him the first of Kirtley’s restitution payments-$35.76.

The case of the fire truck

On April 24, 1986, Jerry Ferguson won a $15,230.06 judgment-but he doesn’t sound very pleased about it: “I’d never do it again,” he says. “It was a nightmare.” Ferguson is referring to his case against the Ford Motor Company concerning his purchase of a 1985 Ford F-150 Su-percab truck. The truck was a lemon, and to get his money back, Ferguson used the “lemon law,” passed by the 1983 Texas Legislature and administered by the Texas Motor Vehicle Commission.

The procedure sounds simple enough: you can take your case to the commission if your new car has defects that “substantially impair” the use and market value of the vehicle. You have to file your complaint within six months of the warranty expiration date or within eighteen months of the date of purchase. The same problems must have been worked on-unsuccessfully-at least four times by the dealer, or you must have been without use of the car for more than a month.

In Jerry Ferguson’s case, the trouble began one week after he drove his new truck off the lot when he faced the first of seven engine fires caused by a red-hot catalytic converter. It’s an ironic twist that Ferguson owns an auto repair shop in Van Alstyne, Texas. He and his crew had never seen anything like this truck. Two months after he purchased the truck, he asked Ford to take it back. “I do not feel comfortable with this truck,” he wrote in his complaint letter. “The transmission and motor have been subjected to such extreme temperature so many times, causing irreversible damage. I am willing to pay for the mileage that I put on the truck, but I would like to have it replaced.”

Ferguson’s attorney reiterated his wishes to the Ford Motor Company district office, which offered to honor the warranty and pay $250 to cover Ferguson’s attorney’s fees, but did not offer to replace the truck. The next step was to appeal that decision to the Ford Consumer Appeals Board in Car-rollton, which reviewed the case and decided that Ford’s offer was fair.

That final word was issued in August 1985. In September, the truck caught fire twice more. It wouldn’t shift into reverse or third gears. The air conditioner went out. Three different Ford dealerships had looked at Ferguson’s vehicle over the months, and relationships between Ferguson and the original dealership managers had deteriorated into arguments as red hot as his catalytic converter. At this point, Ferguson resorted to “creative complaining.” He had one of his wrecker drivers tow the truck back and forth in front of the Sherman dealership. He even rented a flashing marquee to perch aboard the wrecker: “Another Lemon From Bob Utter Ford.” Ferguson estimates that he spent more than $4,000 in postage, long-distance phone calls, trips to Austin for commission hearings, and days off work.

Even at the final hearing in January 1986, it looked like an uphill battle. The Ford Motor Company position was unchanged. The company said it felt “customer modifications, tampering, and use of improper fuel” had caused the problems. Ford did offer, free of charge, a three-year, 60,000-mile extended warranty on the truck.

But in the end, the TMVC hearing officer recommended Jerry Ferguson be reimbursed for the full purchase price of the truck, less twenty cents per mile for the miles he had driven it. Ferguson had won, but it had taken a year and three days of fighting.

The case of the missing mechanic

The last thing Ethel Anderson needs is car trouble. The thirty-nine-year-old Dallasite works to support her mentally retarded daughter and her elderly mother. But her 1972 Buick station wagon sits in the front yard with transmission problems Anderson hasn’t had the time or money to fix.

“I can drive it for short distances, like to the supermarket,” Anderson says, “but it cuts out so much, and I can’t afford to get stuck somewhere. Nobody else at home can come get me.”

The car started acting up last fell. Anderson’s former brother-in-law mentioned that he knew a repairman, a guy who often stopped in his cafe for coffee. The mechanic’s name was Roosevelt Andrews. He came to Anderson’s house to take a look at the car, Anderson says, and for $50 down, although she only had $35 to give him, said he would replace a torque converter for a total of $185. Anderson says Andrews told her he was a partner with two other men in “JR&H Auto Repair,” where he took the car to fix it. Later, he revised his estimate: “He said I would need a whole new transmission,” Anderson recalls. “He said the new bill would be $250. I paid him another $160 to get started.”

A month later when Anderson picked up the car, it was out of gas, and during the drive home it had the same problems as before. She called the shop, but couldn’t reach Roosevelt. Instead she talked to a man named Joe, who identified himself as the owner of the repair shop. “He talked real smart to me,” she says. “He told me Roosevelt Andrews just used some space in the shop-he didn’t actually work for them. He told me he just spray-painted my old transmission to make it look new, and put it right back in my car.”

Anderson kept calling JR&H, voicing her frustrations and asking them to take some responsibility for what Andrews had done. She also called Contact 8 and the Better Business Bureau. “The TV station said they would look into it, but I never heard anything,” she says. “The Better Business Bureau got back to me, and told me they couldn’t find an auto repair shop at that address, and the phone had been disconnected. I figured by then, if they can’t even find ’em, I better just hang it up.”

What could Ethel Anderson have done to avoid this situation? We asked Ed Meeks, the auto repair expert who enforces the City of Dallas Motor Vehicle Repair ordinance. The main problem, he told us, is the way the mechanic was chosen in the first place. “It’s like needing surgery and finding a guy in the drugstore who says he can do it for a good price.” Meeks says he has seen cases worse than this one-cases in which the “mechanic” tows the car away and sells it to a wrecking yard. The repair shop broke all kinds of city ordinance provisions. It was unlicensed; Anderson didn’t receive a schedule of charges for the work to be done; and, of course, painting the transmission and representing it as repair work is fraud, pure and simple. But Anderson didn’t know the city could have gone after the shop on her behalf.

Almost a year later, the guarantee is that Anderson will never get her money back. On May 29, a self-employed mechanic named Roosevelt Andrews was sent from Dallas to the Texas Department of Corrections in Huntsville for violating probation on an earlier attempted murder conviction. He is serving a two-year prison sentence.