NOVEMBER 6, 1982, was a Saturday night just like most others in Dallas: That night, a handgun was used to kill or wound someone.

John Morrison, a 22-year-old former employee of The Dallas Morning News, had gone with some friends to drink beer and play pool at an Oak Cliff nightclub. Morrison had played two games when he was confronted by William “Binky” Howard, 21, who wore a silver .38-caliber pistol in a holster strapped to his hip. After a brief argument over who would use the pool table next, Howard drew his gun and fired three bullets into Morrison’s chest. Morrison slumped down the wall, got to his feet and stumbled out to the parking lot, where he died a few minutes later. Howard put on his jacket, slipped his gun back into the holster and went home.

That scenario should have come from the 1880s, not the 1980s. But the gun situation in Dallas-and in most American cities-hasn’t changed much in 100 years. During the last century, Dallas has made astonishing progress in almost every area of life-commerce, health care, education, recreation-but when it comes to guns, as it so often does, we’re still a part of the Wild West. Guns are as Texan as armadillos.

In Dallas, it’s absurdly easy to buy a small, concealable handgun, whether it be a cheaply made .22 revolver or a snub-nosed .357 magnum that packs almost the firepower of Dirty Harry’s famous cannon-but with a two-and-a-half-inch barrel. These lethal toys fit nicely into a coat pocket or a boot, and they are used in alarming numbers to kill, maim and rob Dallas-ites. Our only consolation may be that other cities, many without our recent frontier heritage, are also part of the handgun culture.

Of Dallas’ 306 murders during 1982 (the last year for which complete figures are available), 59.8 percent were committed with handguns. That’s actually lower than the figures for 1981, when 62.3 percent of our 300 victims met death from pistols of various sorts. Handguns are the murder weapon of choice in Dallas, as they are everywhere else in the country. According to Justice Department figures, 11,721 murders were committed with firearms in 1982. Of those, 8,474 were committed with handguns. Add the accidental shootings and suicides with handguns, and the handgun death toll in America exceeds 20,000 lives each year.

In Dallas, as in most of the country, anyone can buy a gun. Oh, there’s a little form to fill out. You’ve got to be 21, and you must promise that you’re not a felon, a drug addict or an adjudicated mental defective. Then you show your driver’s license, plunk down your money (as little as $25 for a Saturday Night Special in a pawnshop), and you’re a proud gun owner. The law forbids you to carry a concealed weapon, but no law prevents you from buying one that’s easily concealed.

But perhaps you’re wondering about that form you fill out. What happens to it? Does it go off to Big Brother in Austin or Washington? Does the government know you’ve got this thing?

Unbelievably, nothing happens to the form; it stays there in the store. Nobody even checks to see whether or not you’ve told the truth. Not in Texas. Your purchase doesn’t become part of any computerized central file anywhere. Unless, by some odd turn of events, the gun is traced back to the store, nobody but the store owner need know you’re packing a deadly weapon. It’s your little secret.

To some people, this may sound like protecting the right of privacy. But consider an analogy: What if you bought your car at a dealership and registered it at the dealership? Only the people at the car lot would have a record of your purchase. And if your car was stolen or used in a crime, the police would have a hard time tracing it because only the dealership would have your license number.

Imagine the chaos. And to make the analogy more precise, what if the car registration laws differed from town to town and state to state? Suppose Piano had a tough registration law while Mesquite had none? Where do you think people would go to buy a car that might be used in a robbery? Let’s add one more parallel: Imagine the turmoil on our roads if most cities and states didn’t require you to be licensed or pass any kind of test showing that you could drive a car. Instead, you sign a little form stating that you’re not a bad person, then you drive off in your new Mustang.

If you can picture this rolling nightmare, you’re starting to understand the handgun epidemic. We have a situation that should appall us. We’re a country of-how many handguns? At least 40,50 or 60 million, according to most estimates, but really, nobody knows. And that should worry us, too. We know how many sugar cubes we import and how many yards of denim we export, but we don’t know how many deadly, pocket-sized weapons are out there.

Our society would never tolerate such confusion with car registration. Cars have many legitimate uses, but they are also potentially dangerous to others, so no one gets behind the wheel until some official of the state certifies his driving. No one gets title to a car until the car is registered with the state. Yes, these are minor infringements on our freedom, but in the interest of the common good, we take the driving test and we register the car. In exchange for the privilege of driving around in a couple of tons of metal, we give up a few bytes of our privacy to Big Brother. Those not interested in making the trade are not forced to drive cars.

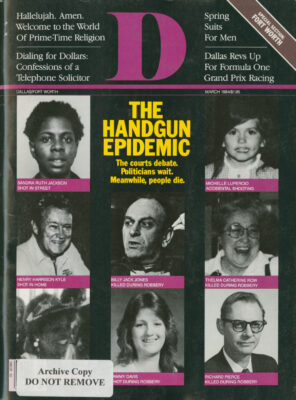

But when it comes to handguns, the notion of the common good is quickly forgotten. When handguns are used to kill Billy Jack Jones, a highly talented voice teacher at the Dallas Theater Center; or Richard Pierce, a respected scientist with Mobil Oil, (see page 60) we collectively throw up our hands and say that, yes, criminals are awful, but nothing can be done.

That’s not true. Something-several things-can be done, to cut down on guns and to cut down on crime.

According to the National Rifle Association (NRA), the Gun Owners of America and the Second Amendment Foundation- the leading pro-gun groups in America today-gun control is a very simple matter. The NRA views any type of gun control as merely the insidious first step toward government confiscation of all firearms, notwithstanding that no organized gun control group suggests any sort of restriction on shoulder arms and sporting guns.

“Wherever we have had gun control, it has resulted in tyranny,” says Herb Chambers, Texas field representative for the NRA. “I’ve been to countries like Chile, which has very strong gun control, and seen people strung up by their toes. Not one honest citizen could defend himself. Why? Because nobody had guns.”

Lost in the thunder of rhetoric is the truth: Between the NRA’s 1984-style scenario and our bloody status quo are several alternatives that would introduce some sanity into our irrational gun culture:

-Mandatory prison sentences. Everyone is against crime, so it’s no surprise that this notion pleases everyone. If a person commits a crime with a handgun, tack on extra years to his sentence and don’t grant parole or early release. Currently, the U.S. Congress is considering two bills that would provide mandatory sentencing: The Kennedy-Rodino Handgun Crime Control Act and the McClure-VolkmerBill.

-Tougher requirements for becoming a dealer. Selling guns is as easy as buying them. A three-year dealer’s license costs only $30. About 98 percent of requests for licenses are granted by the Treasury Department’s Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms (BATF), the agency charged with enforcing federal gun control laws. According to BATF figures, Dallas County has more than 2,100 licensed gun dealers, but only about 30 percent of those licensees run storefront operations. Of the rest, about half are legitimate dealers and half are selling guns out of their homes or cars. But regardless of their ethics, gun dealers need not worry about the BATF snooping into their records. “It takes approximately six hours to do a check,” says BATF Regional Firearms Advisor Dan Coleman. “If we checked all the licensed dealers in the county just once a year, it would take seven agents their total man-hours for the year to do it. And we only have six agents in the Dallas area.”

-A waiting period and a background check. “This immediate access to handguns is unacceptable,” says Cpl. Dick Hickman, president of the Dallas Police Association. “It’s a total farce to just ask them for their identification, check a few blanks on a form and let them pick out a gun.” Fifteen states already require a waiting period ranging from 48 hours in Alabama to 15 days in California; 25 states provide an opportunity for a police check on the buyer’s background. Gun control proponents argue that a waiting period has another benefit: It provides a “cooling-off period” that may keep domestic squabbles from becoming murders.

-A system of registration. Some states require every handgun transferred from one person to another to be registered with the police, much like the system used for registering cars. Under a partial registration system, handguns bought from licensed dealers must be registered. Dealers must send copies of the registration forms to a designated law enforcement agency. Various types of information about the purchaser and the handgun can be included on the form.

-A system of licensing. The toughest kind of licensing puts the burden on the applicant to show why he should own a gun. In New York City, for example, an applicant must show that he needs a gun to protect his business or large sums of money he must carry. More permissive licensing allows anyone not in a prohibited category (felons, drug addicts, mental patients) to obtain a license and a gun. Various states require licenses to purchase, to carry or to possess a gun.

-A ban on private ownership of handguns. This extremely controversial measure is politically impossible in most parts of the country. Recently, the California courts struck down a San Francisco ordinance banning handguns, but the U.S. Supreme Court refused to overturn a ban in Morton Grove, Illinois. No proposed ban would deny handguns to police officers, military personnel, sporting groups or licensed collectors.

-A ban on the manufacture and sale of Saturday Night Specials. According to most definitions, this would prohibit non-sporting handguns that have barrels of less than 3 inches. Millions of Saturday Night Specials still would be available, but such a ban eventually would reduce the number of handguns in circulation. The 1968 Gun Control Act prohibited the importation of non-sporting handguns, but failed to do the same for their parts. Enterprising gun makers bring in the parts and assemble the guns here, thus circumventing the intent of the law. In addition, we have our own cheap, domestic handguns.

SO GUN CONTROL is a much more complex issue, with a much broader range of choice than the pro-gun organizations would have us believe. And gun control is not simply the pet project of bleeding-heart liberals and weak-kneed pacifists. Seven major national commissions on crime have called for strong handgun controls. The 1981 Attorney General’s Task Force on Violent Crime recommended a mandatory background check on every handgun purchaser as well as a ban on the importation of handgun parts. The 1969 Eisenhower Commission on the Causes and Prevention of Violence, formed after the civil disturbances of the Sixties, concluded that “the only sure way to reduce gun violence is to reduce sharply the handguns in civilian hands in this country.”

And the list goes on. In 1981, the Surgeon General’s Select Panel for the Promotion of Child Health reported “an epidemic of deaths and injuries among children and youth” and traced the cause of the epidemic to one source: handguns. Former FBI Director Clarence Kelley made no secret of his desire to control Saturday Night Specials; neither did the U.S. Conference of Mayors, which passed a standing resolution in 1975 calling for public education about firearms. “Americans have been denied access to complete and accurate data on the issue,” the conference report stated. Locally, The Dallas Morning News has taken an editorial stance against gun control, while the Dallas Times Herald has called for stronger controls, including extensive background checks of potential handgun buyers.

Even presidential candidates Walter Mon-dale and John Glenn have called for stricter handgun control. Mondale favors a national ban on handguns with barrel lengths of 3 inches or less; Glenn supports a national waiting period of 21 days for a handgun purchase. Both candidates also fevor closing the loophole in the 1968 Gun Control Act that allows foreign handgun parts to be imported.

Repeatedly, opinion polls have shown that the American people support responsible gun control measures (for Texans’ views on gun control, see box below):

-Associated Press/NBC News Poll (April 1981): 71 percent favor a law requiring a person to obtain a permit before buying a handgun.

-Washington Post/ABC Poll (April 1981): 65 percent favor stronger legislation controlling the distribution of handguns.

-Gallup Poll (July 1981): 91 percent favor a 21-day waiting period before the purchase of a handgun, during which time authorities could check the prospective gun owner’s background.

-Harris Survey (August 1982): 66 percent favor a federal law requiring that all handguns be registered with federal authorities.

But in Texas, the will of the people has not been heeded. The Texas state law regarding firearms possession is one of the most lenient in the nation; it even provides a giant loophole that allows possession of a gun by anyone who is “traveling,” but then fails to define what is meant by traveling. Does driving from Lake Texoma to Dallas constitute “traveling”? How about driving from Balch Springs to Richardson? Garland to White Rock Lake? Apparently, each policeman must decide who is traveling and who is merely driving with a gun.

In the city of Dallas, the issue of gun control has never made a whimper, much less a bang. Texas has no pre-emption law barring cities from passing their own gun control laws, but according to the City Secretary’s office, there has never been a formal City Council debate here over any type of gun control measure. In 1981, Mayor Jack Evans declared the week of October 25-31 to be “End Handgun Violence Week,” but such official proclamations carry only ceremonial importance.

But Dallas should not feel alone. The BATF reports that only two Texas cities-Midlothian and the Houston suburb of Southside Place-forbid the sale of guns. And only Wichita Falls requires that guns bought in the city be registered with the police.

The Wichita Falls ordinance could serve as a model for Dallas. The police department requires extensive information about the prospective buyer, including previous address and occupation for the past 12 months, fingerprints and a valid signature. A full description of the pistol sold is also mandatory and must include make and model, serial number and the manufacturer’s name.

SO DALLAS FINDS itself solidly with the majority. So much death and violence; so little effort to stop it. In this city, voices against the handgun are voices crying in the wilderness.

One such voice is State Rep. Paul Rags-dale. If any of his gun control bills had ever passed the Texas Legislature, he might be known as “Mr. Gun Control.” He’s met with failure in every session since his election in 1975, but the disappointment has not lessened Ragsdale’s desire to fight the handgun epidemic (for the views of other area legislators, see page 65).

The five-term representative from South Dallas County began his efforts in hopes of stemming the rising tide of black-on-black crime. In Dallas, blacks murder each other three times more often than whites; the majority of those killings are with handguns.

In 1975, two of Ragsdale’s constituents, an estranged husband and wife, happened to visit an Oak Cliff nightclub at the same time. A shouting match ensued. To settle the matter, the wife pulled a pistol from her purse and fired at the husband. The first round missed him, but struck and killed a 22-year-old waitress, the mother of a 3-year-old child. Then the wife “just assassinated the guy,” Ragsdale says. The incident has stayed with him to this day.

“That’s when I got involved in handgun control,” Ragsdale says. “These weapons are concealable, and that’s their greatest danger. You never know when somebody’s got one. You couldn’t exactly conceal a rifle in a bar.”

Ragsdale’s first handgun control bill, introduced in 1975, was a formidable package of restrictions that, if passed, would have made Texas one of the most progressive states in the control of handguns. The bill provided for the licensing of handgun owners and mandated a fine and prison sentence for anyone transferring a gun to an unlicensed person. In addition, Ragsdale’s Handgun Regulation Act declared “substandard” any handgun that did not meet certain rigid criteria (among them, a melting temperature of at least 1,000 degrees) and banned the manufacture and sale of such guns.

Ragsdale’s bill was not even given a hearing. He received some moral support from San Antonio legislator Ben Reyes and little else. Back in the mid-Seventies, Texas was even more barren ground for gun control than it is now.

So Ragsdale learned the art of compromise. In each succeeding legislative session, he refined his bill and pared down its more “radical” proposals. He put the ban on Saturday Night Specials in a separate bill (“I didn’t want all my eggs in one basket,” he says) and created a new bill requiring two forms of identification for a handgun buyer and a 72-hour waiting period between sale of a gun and delivery. Antique firearms and curio guns were exempt from the bill.

But even this more moderate approach has met with no success in Austin. In the 1977 and 1979 sessions, Ragsdale’s bills were never heard by a committee. In 1981, after the shootings of the Pope and President Reagan, it seemed for a time that public revulsion might force some action on gun control. Gov. Bill Clements floated a trial balloon hinting at approval of gun control legislation, and Ragsdale’s much-revised, much-reviled bill was finally heard in front of the transportation committee chaired by Jim Nugent, now on the railroad commission. According to Ragsdale, Nugent submarined the bill from the very start.

“Nugent notified the damned NRA that I was having a hearing on the bill,” Ragsdale says. “I wondered why all those pickup trucks with guns and gun racks were surrounding the capitol that evening. Little did I know, they were waiting on my hearing. They must have had 300 people in there. It scared the hell out of me.”

It was Ragsdale’s introduction to what many consider the most powerful single-issue lobby in America, and their tactics against the Ragsdale bill were the same ones they have used against countless state and federal legislators for three decades (see page 65). The NRA spokesmen used the “camel in the tent” reasoning that has made them famous: Once the camel of gun control gets even the tip of his nose inside the tent, watch out. Before you know it, the whole camel will be in, and, according to NRA literature, all types of guns and ammunition will be whisked away by the minions of Big Brother, who may be knocking on your door next. As the NRA’s Chambers puts it: “Wherever they’ve had gun control, it’s turned into gun confiscation. And gun confiscation turns into people confiscation, like with the Jews in Nazi Germany.” Ragsdale’s witnesses, including some police officers, were no match for the NRA rhetoric.

“They’re a bunch of antagonistic rascals, I’ll tell you,” says Ragsdale. “They thought I was out there to outlaw Mom, the flag and apple pie. But they’re not the National Handgun Association, after all, and they would profit from dissociating themselves from Saturday Night Specials.”

The NRA arguments were not novel, Ragsdale recalls-just loud and long. “They’re basically paranoid about any at-tempt to do anything about firearms. I can’t possibly see how handgun regulation is related to rifle regulation, and nobody in the world that I know of advocates banning rifles and shotguns. But I think we do have a right to ban Saturday Night Specials, just as we have a right to ban ownership of a bazooka.”

But few other legislators were persuaded, and Ragsdale’s bill died in committee. “They just laughed at him,” recalls State Rep. Bill Blanton. “They were in no mood to pass any kind of gun control bill.”

The cornerstone of the NRA’s unyielding opposition to gun control lies in its reading of the Second Amendment. If you drive past NRA headquarters in Washington, D.C., you’ll find part of that amendment chiseled in stone above the doorway: “The right of the people to keep and bear arms shall not be infringed.” But that’s only part of the amendment, which reads in full: “A well regulated militia being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear arms, shall not be in fringed.”

Perhaps it says something about our history and civics classes that so many people don’t miss these omitted words, which make all the difference. Could the Founding Fathers have intended to keep from the states all power to make firearms laws? Did they mean to protect our “right” to be shot down in a 7-Eleven by a drug addict carrying a tiny pistol? Handguns in the modern sense didn’t even exist when that amendment was written.

Again, that opening clause: “A well-regulated militia.” Unless you want to say that every red-blooded American is a one-person militia and therefore needs to tote a gun, this is the word that trips up the NRA. James Madison proposed the Second Amendment to satisfy delegates who feared an oppressive central government. Hence the need for an armed militia; if the national government became too bellicose, the brave men of the state could grab their muskets and do something about it. Today, most scholars say that the Second Amendment guarantees a collec tive right to form a militia-or, we would say, a national guard-not an individual right of unlimited access to handguns.

But if the NRA and its sympathizers could be persuaded by reason or the dictates of the courts, this debate would have ended long ago. The Supreme Court has held on at least five occasions that the right to keep and bear arms is collective, not individual. Every time the Supreme Court has addressed the issue, from U.S. vs. Cruickshank (1876) to the recent Morton Grove, Illinois, ban on handguns, it has disagreed with the NRA position. There is no absolute right to bear arms, any more than there is an absolute right to free speech or free assembly.

It would be ironic indeed if the Second Amendment, intended to broaden our freedom, were twisted into a new kind of tyranny. Are we condemned to the “freedom” of living with 50 million handguns? Between 1963 and 1973, more Americans were killed with handguns than died in the Vietnam War during the same period-and they were killed here at home with perfectly legal weapons.

For Mike Renquist, pastor of NorthPark Presbyterian Church and president of Tex-ans for Handgun Control (THC), gun control is too important to leave to the legislators. Renquist admits to “an abhorrence of weaponry” from an early age, and his dislike of guns deepened when he ministered to shooting victims at Austin’s Brackenridge Hospital. But it was the handgun murder of former Beatle John Lennon that galvanized Renquist and his teen-age son, Christopher.

The Renquists had spent happy hours listening to Beatles songs, singing along with the radio as they drove in the car. Lennon’s work was a common bond for the family. When he was killed, the Renquists decided to get involved.

But getting involved with gun control in Dallas takes some doing. Renquist checked with Washington-based organizations such as Handgun Control Inc. and the National Coalition to Ban Handguns (NCBH), expecting to find a network of gun control sympathizers spread across the nation. Instead, he learned that gun control virtually dies at the Mississippi. Renquist could find no organized opposition to handguns across the South and the wide-open West. Then, after the attempt on Ronald Reagan’s life in March 1981, a friend of Renquist’s started THC. Today, with some 40 members, the group is small but dedicated. Its budget doesn’t permit advertising or an office, so meetings are held in members’ homes. Still, Renquist says, it’s a start.

When THC was first chartered, the group followed the lead of the NCBH, working for the eventual prohibition of all types of handguns, not just Saturday Night Specials. But like Rep. Ragsdale, Renquist and his fellow members learned that gun control in Texas must start by taking one very small step at a time. Today, Renquist regards a total ban as “ridiculous.” In part, the change came about as a result of many obscene phone calls and hate letters he received after appearing on radio and TV talk shows.

“Texas, with its sense of frontier justice, has enough kooks walking around [to prevent such a ban],” Renquist says. He believes that the “total ban” mentality of the NCBH has played into the hands of the gun zealots. “The issue has been clouded to an all-or-nothing status. What we’re talking about now is stopping the sale of the Saturday Night Special, defined as a non-sporting handgun with a barrel less than 3 inches long. You can’t tell me that a person who wants a sporting gun or a gun for protection is going to buy a cheap little gun that might blow up in his hand.”

Renquist believes that there is a connection between the availability of guns, suicides and crimes of passion. He cites the case of one of his church members, a young woman who had been undergoing psychiatric counseling. One night, the woman received some bad news. Distraught and unable to reach her counselor, she went to a gun store and bought a handgun. Then she drove to Renquist’s church and killed herself in the parking lot.

“If she had taken pills or tried some other method, we might have gotten to her,” Renquist says. Statistically, he is correct: Suicide attempts with handguns are five times as likely to be successful as attempts by any other means.

As a minister, Renquist is faced with a special problem: He must speak a message of love and brotherhood while troubled by the knowledge that our gun laws make it easier for us to destroy one another. And he must be careful not to alienate the pro-gun members of his congregation.

“As I try to interpret the Word of God in the pulpit, I’ve spoken many times against violence and in support of gun control,” Renquist says. “I don’t know how fired-up that made my NRA people. But this is a moral issue. We need to take a hard look at Dallas, at the morality that brings about this kind of thing [handgun violence].” But moral suasion without stronger gun laws seems futile to Renquist. “It’s like putting an ice cream stand on every corner and then complaining that people are getting fat,” he says.

The charter of THC doesn’t spell out the specific measures favored by the group, but Renquist says he would begin with a crackdown on illegal gun sales at flea markets and gun shows. “I go to Canton, to First Monday and I see guys walking by with a pistol on each finger, trading and bartering. I’ve never seen a form filled out.” He says that gun dealing “should be recognized as the serious business that it is” and calls for increasing dealer licensing fees to $200 or more and requiring a mandatory background check on gun buyers.

As a clergyman-turned-activist, Renquist is keenly aware of the psychological contradictions of an armed society. “You have people with weapons in their homes who would do anything at the drop of a hat to protect themselves, and yet they worship a God who loves life. It just doesn’t make any sense. I try to preach what I believe, which is that God is a lover of life and not of death and destruction.”

Another Dallasite against handguns is Windle Turley, a lawyer specializing in products-liability cases. Turley brought suit for the plaintiffs in the first airline “crash-worthiness” case in Texas and won large setdements for 30 people in the fall of the Texas State Fair’s Swiss Skyride. Now, Turley is trying to extend the protective umbrella of products-liability law to cover the victims of handgun shootings.

Turley lost the first of his handgun cases (he has filed 15 around the country) in January when a Dallas jury ruled against his client, 21-year-old David Clancy. Turley had argued that Clancy should be allowed to recover $26 million in damages as a result of an accidental shooting that left him a quadriplegic. The gun was made by a company called Armsco and was sold in a Le-vine’s department store owned by the Zale Corp.

Along with writer Terry Southern, actor Eli Wallach and others, Turley serves as an adviser to the National Coalition to Ban Handguns. But he insists that his handgun cases are merely an extension of traditional products-liability law, not a personal crusade. “It’s a natural function of the work we do here,” Turley says of his 20-member firm. “Tort law exists to prevent injuries, and when it doesn’t work, we compensate the victims. If the community has an area of risk where death and injury are occurring because there is no tort therapy, that’s where we need to be looking.”

Turley’s gun cases are against different manufacturers and are based on different theories of responsibility, with one common denominator: “The theory is that gun suppliers have a responsibility to victims because the utility of their product to society does not measure well against the enormous hazard and risk it poses,” he says.

According to Turley, the country loses $15 billion per year to handgun violence, considering losses in medical care and “the investment in human resources” that is lost. In the Clancy case, he argued that no social benefit provided by handguns could possibly outweigh such losses.

In almost all of Turley’s handgun cases, the defendants have filed motions to dismiss on the grounds that the state does not afford such a remedy to handgun victims. Judges have granted the motion in only one case, and that is encouraging to Turley. If he wins even one case, the decision would clear the way for an avalanche of similar suits.

“The gun makers will have to give thought to whether their profit from the distribution of these products will justify the added cost they have to pay the victims,” Turley says. “I believe the cost will be so large that it will result in substantial changes in the gun marketing scheme in this country and probably changes in the type of handgun marketed.”

Turley crossed paths with the NRA almost two years ago, after a 60 Minutes report on his work in progress. The NRA has sent out a special request to its 2.5 million members asking for funds to fight the Turley suits and similar actions being brought by other lawyers. The group has filed a friend-of-the-court brief in a pending case in the 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals.

“They can’t be objective about anything,” Turley says of the NRA. “They’re so paranoid, they think that banning Teflon-coated bullets will lead to banning the locks on our doors. They have misrepresented what’s going on in this handgun project so many times. One of their sources went on TV to say that I wouldn’t stop with handguns, that next I’d want rifles, too.”

The NRA firmly disagrees with Turley’s efforts to make gun manufacturers and sellers liable for damage caused by their products. “You could generate a monster from this that would extend far beyond handguns,” says Herb Chambers. “Mr. Turley does real well in his verbiage, but this is the first time he’s been able to get one of these cases into court, and he lost.”

Turley is seeking a new trial in the Clancy case. He says that the jury “never even considered the issue the court put to them.” Turley believes that the jurors’ 10-2 vote was based on the fact that sale of the gun was legal, an irrelevant consideration in a products-liability case. He was disappointed but not deterred; the Monday after the decision was announced, he flew to San Francisco for another handgun case.

“It’s a war on unnecessary death and injury,” Turley says. “All the commercial aviation fatalities in the world since the time we began flying do not equal the number of people who will die from handguns this year.”

Some observers question whether Dallas was the best place to launch such an unorthodox legal campaign, suggesting that San Francisco or Boston might be a better testing ground. And some of Turley’s peers are wary of his efforts, fearing that a string of successes could bring a public backlash against products-liability cases in general.

“He’s one of the greatest products-liability lawyers this country has ever produced,” says one Dallas attorney who asked not to be named. “I’m not sure there’s a plaintiffs products-liability firm in the country that can match them. But I have extremely mixed feelings about the handgun project. I’m afraid that other juries will be turned off by such an extension of liability.”

David Noteware, a Dallas defendants’ lawyer in liability cases, is blunt about Turley’s efforts: “I don’t own a gun, and I don’t want one. But it seems to me that we’re starting to legislate morality through judicial fiat, and that’s the wrong way to do it.” Noteware agrees that a manufacturer who knowingly distributes a defective product should be responsible for damages to a consumer, but he says that some products carry an inherent danger in their very conception.

“Take ladders, for example. People who make them know that some people are going to fall off the ladders. But should they be responsible when someone falls? Not if the ladder was properly built. I’m all for unfettered access to the courthouse, but I don’t think courtrooms are the place to decide which products should be made and sold. That should be done in the marketplace.”

Besides their Second Amendment argument, the NRA has another running objection to gun control. It claims that gun control laws simply don’t work. “They are ineffective in stopping crime, and they place a burden on the law-abiding citizen,” says John Adkins of the NRA’s Communications Division in Washington, D.C.

Again, the NRA’s astounding first premise comes into play. The group denies any connection whatsoever between the number of guns in our society and crime, murder or suicide. The violence this does to common sense is clear: Most of us would say that if we had fewer cars, we would have fewer car wrecks; if the marijuana supply were cut in half, fewer people would get high; if we had more policemen, more criminals would be caught. Apparently, the NRA would be forced to deny all these connections, since by its logic the availability of handguns has no link to any wrongdoing in society. Presumably, if we had half as many handguns floating around, criminals would simply double their efforts and the crime rate would remain the same.

Nor is the NRA persuaded that Saturday Night Specials, despite their limited uses in target shooting and hunting, pose any menace to society. “The only difference between a Saturday Night Special and an $800 target gun is a hacksaw blade,” Chambers says. “The government has never even come up with any suitable criteria as to what is a substandard handgun. Really, it all comes back to the Second Amendment. It’s your right to have a gun. What you can afford is an individual matter.”

It would be stupid and naive to think that gun control laws, however rigidly enforced, would end crime and rebuild the Garden of Eden. The NRA is right to say that criminals will always be able to get guns. But this argument ignores vital facts: A great many of the handguns used in violent crime are stolen from the homes of law-abiding citizens. One authority puts the number of stolen handguns at 225,000 a year. But in Weapons, Crime and Violence in America, James D. Wright estimates that 275,000 handguns were stolen in 1975 alone. A 1979 BATF study of Philadelphia crime showed that half the handguns confiscated by police that year had been stolen. In other words, there is no way to be sure that only good guys have guns, since bad guys love to steal guns from good guys.

And although handgun crime is a grave problem, it’s not the only menace that grows from those very short barrels. The Dallas Police Department’s Murder Analysis 1982 shows that more than one-third of that year’s murder victims were killed by family members or friends. Nationally, the figure is even higher. According to the FBI’s Uniform Crime Reports for 1982,54.8 percent of the murders occurred between people who knew each other. These figures suggest that even if gun control didn’t reduce crime, valid reasons would still exist for making handguns harder to get.

Without a strong federal law, it is impossible to keep guns bought in one place from being used in another. One city or state may institute strong gun control, but if neighboring cities and states have lax laws, the effects of the tougher laws will be diluted. Still, the limited data that exist show the value of gun control in reducing crime.

Consider New York City. Its Sullivan Law is one of the oldest, strongest gun control ordinances in America, providing for a strict licensing system and an extensive background check on anyone purchasing a handgun. Gun lobbyists love to talk about the New York City crime rate as proof that gun laws don’t work, but a BATF study showed that of 2,546 guns used in New York City crime, only 4 percent were bought in the state; the rest were imported from states with weak gun control laws. More than 45 percent of those guns came from South Carolina, Florida, Georgia and Virginia, which gives a new meaning to the term “Solid South.” The implication is clear: The New York law works, but it cannot police the nation.

South Carolina, once the gunrunners’ capital of the country, provides an even more striking example of the efficacy of gun control. After several media exposés of the states’ black-marketing guns to other states, South Carolina passed rigorous laws including a seven-year mandatory sentence for crimes with a handgun and a ban on Saturday Night Specials (defined as handguns with die-case frames and melting points of 800 degrees). Citizens could buy one handgun per 30-day period, but only after obtaining a state-issued photo identification card and being fingerprinted. For the first time, gun dealers were licensed by the state.

The results were startling. In 1974, before the laws were passed, South Carolina had 264 handgun murders, which accounted for 58.4 percent of the state’s total murders. In 1975, the year gun control came to South Carolina, those numbers dropped to 227 and 53.9 percent. By 1976, the state reported 147 handgun murders (fewer than Dallas has in a typical year); only 44.9 percent of the state’s murders were committed with handguns-a drop of 13.5 percent in three years. And lest it be thought that South Carolinians just became peaceful during that time, the number of aggravated assaults during the period increased sharply. Again, the evidence suggests that guns do kill people and that although gun control will not produce instant pacifists, it can reduce the number of murders.

The experience of other cities and states is equally encouraging. In 1974, Massachusetts passed its Bartley-Fox Amendment requiring a one-year prison sentence for carrying a handgun without a permit. Six years later, the Boston murder rate had declined by 32 percent; handgun murders were also down 32 percent in 1976. The same dramatic effect was seen when Washington, D.C., passed a handgun “freeze” limiting ownership to those who had registered their handguns before the freeze went into effect. Three years later, handgun murders, assaults and robberies all showed significant declines.

BESIDES THE organized efforts of the NRA, Gun Owners of America and the Second Amendment Foundation, gun control has fared so poorly in this country for another reason: The gun lobbies have been allowed to seize the high ground on the crime issue.

The NRA claims that America’s crime problem stems from permissive judges, not from a surfeit of handguns. It cites the example of Israel, where murderers serve a mandatory life sentence and murder suspects are denied bail; or Japan, which has a 99.5 percent violent crime conviction rate and does not permit plea bargaining.

These are telling points. When convicted murderer Dan White is released from prison after serving only five years for the handgun killing of a San Francisco mayor and City Supervisor, something is very wrong. Of course, gun control groups are against crime and believe that reducing the number of guns in society will reduce the crime rate, but the NRA has been able to define the issue: We are against criminals; you are against law-abiding people who only want to protect themselves.

As long as we labor under this false dichotomy, the NRA will continue to spook any politician who so much as breathes “gun control” in his sleep. Right now, gun control is so unpopular among our legislators- despite the findings of the Texas Crime Poll-that they can almost be excused for their ignorance on the subject. Why spend weeks researching an issue that stands little chance of coming to a vote-unless, of course, you plan to lead on the issue of gun control (often a kamikaze mission) and not merely climb on the bandwagon if it ever gets rolling.

IN THE MEANTIME, the NRA is calling the shots. How far will the group go to have its way? Consider two recent elections.

“Gun control is political death,” says an aide to Democratic Rep. Tom Vandergriff of Arlington, who squeaked into the U.S. House of Representatives in 1982 after winning the closest House race in the nation. Vandergriffs Republican opponent, Jim Bradshaw, was backed to the hilt by the NRA. According to the Federal Election Commission, the NRA gave Bradshaw more than $12,000 in direct contributions and expenditures on behalf of his candidacy. The Gun Owners of America also funded Bradshaw.

Handguns were not much of an issue in the 26th District, but Vandergriff made the mistake of appearing a bit too thoughtful on another subject: He mused aloud during the campaign about outlawing the armor-piercing “cop-killer” bullets, the Teflon-coated ammunition that slides right through a policeman’s bulletproof vest. To the astonishment of law enforcement people everywhere, the NRA opposes a bill that would outlaw such bullets. Vandergriff said that he’d wait and look at the legislation in its final form, and that was his mistake. Throughout the very tight race, the NRA peppered Vandergriff with accusations that he was anti-gun and anti-hunter.

“We think it was unfair and untrue,” says the Vandergriff spokesman. “Mr. Vander-griff does not favor gun control, and his statements showed that he does not.” To date, no squirrels or deer have been seen wearing bulletproof vests, so it’s hard to see why a “sportsman’s lobby” like the National Rifle Association would need such bullets. But anyway.. .

Then there was Dallas’ 1982 3rd District race between Steve Bartlett and Kay Bailey Hutchison. The two candidates, as neatly matched a pair of conservative bookends as one could want, found themselves locked into a runoff election.

A few days before the runoff election, the NRA flooded the 3rd District with some 15,000 letters endorsing Steve Bartlett. The NRA had discovered that as a member of the Texas House seven years earlier, Hutchison had voted for a bill requiring safety standards for cheap handguns.

Bartlett won the election and breezed through token Democratic opposition in the general election. Today, Bartlett says the NRA endorsement was only one of several factors in his victory. Hutchison, herself a gun owner, believes that the NRA swayed the election.

As long as there is such a dearth ofknowledge about gun control among votersand legislators alike, the NRA and its ilk willbe able to fill the vacuum of ignorance withhalf-truths, playing on the emotions of apublic frightened by crime and unsure ofhow to fight it. Masquerading as patriots,the gun zealots will continue to aid and abetcriminals in the most direct way-by preventing any reasoned efforts to control thechief tool of crime: the small, concealablehandgun.

Armsco and the man

LAWYER WINDLE Turley foresees a time when handguns will be marketed like prescription drugs: available to the public, but not sold indiscriminately for the asking. “I can see them marketed to law enforcement people and sport-shooting clubs for on-premises use,” Turley says. “But this business of just willy-nilly marketing them to the general public is unacceptable for a product carrying such a large risk.”

Last January, a Dallas jury disagreed, refusing to award plaintiff David Clancy the $26 million in damages that he and Turley sought against Armsco, the company that made the .22-caliber pistol that paralyzed Clancy, and against the Zale Corp., which sold the gun through one of its Levine’s stores.

Some jurors seemed to think that they were being asked to rule on the issue of gun control-to “remake the law,” as one put it. Of course, in a sense that is precisely what they were asked to do: provide a judicial remedy for a tangled social problem. Juries in countless other products-liability cases have not hesitated to “remake the law” if attorneys could show that a product was inherently hazardous and was marketed in such a way that its harmful effects were foreseeable by its makers and sellers. But cases involving airline crashes, defective fuel tanks and other products lack the political overtones of a handgun case. Although Judge Nathan Hecht barred discussion of alleged “rights” to bear arms, hoping to prevent the trial from becoming an exchange of slogans and rhetoric, attorneys for both sides reminded the jury that it was breaking new ground in a landmark case.

Considering the evidence heard during three weeks of testimony, it seems clear that Turley made his points, but it’s no surprise that he lost the case. Beyond a reasonable doubt, Turley showed that handguns wreak enormous damage on society. He brought in a covey of expert witnesses-not merely gunsmiths and safety engineers, but representatives of the social sciences as well-including Dr. Leonard Berkowitz, a professor of psychology at the University of Wisconsin and author of the influential Roots of Aggression, a study of the causes of violence. Each expert buttressed Turley’s risk vs. utility argument, showing that handguns do far more harm than good in society. One expert’s studies showed that Texas, Oklahoma and Arkansas-three states with very weak gun laws-have three times as many handgun homicides, four times as many accidental gun-related deaths and eight times as many handgun suicides as do New York, Connecticut and Massachusetts, states with stronger gun laws. Another study, intended to refute defense claims that a gun owner’s sense of safety constitutes a valid social benefit, showed that homeowners actually use their guns in less than 2 percent of robberies and assaults-and that when they do use their guns, they are eight times as likely to be killed than are citizens who do not resist. One criminologist demonstrated that the burglary rate is actually higher, not lower, in cities with high percentages of handgun ownership. The reason? Handguns are a prime target for burglars. So much for self- protection.

Turley had more than academic expertise on his side, however; he also had common sense. The harmful effects of handguns are clearly foreseeable by the makers and sellers of guns. In a society with lax gun laws, a handgun released into the stream of commerce can wind up anywhere-in the hands of a child, a depressed senior citizen or a cocky teen-ager showing off for friends, as Kenneth Hacker was doing when he accidentally shot and paralyzed David Clancy. The chain of responsibility was clearly established.

And yet, it was just at this point that Clan cy vs. Zale became something truly unprecedented in American legal history. What nobody wanted to come right out and say-especially with the pathetic Clancy nearby in his wheelchair-was that the Armsco snub-nosed revolver did just what it was supposed to do and it did it well. When the $19 handgun was fired, it sent a bullet through Clancy’s spinal cord, severing all but a few millimeters of tissue and leaving him paralyzed for life. What else, really, is a Saturday Night Special supposed to do? Described by experts as “a lethal piece of junk,” the Armsco snubbie and millions of similar handguns are useless for target shooting and hunting, but they are favorites of the 7-Eleven robber and the poolroom killer.

What became clear in the 95th District Court was this: We have created a society in which handguns are boringly common. Texas gun laws invite murder and armed robbery, put suicide within easy reach and make accidental shootings a routine matter. The Clancy jurors didn’t want to remake the law or “send a message” to gun makers, as Turley urged them to do. Instead, the jury sent a different message: Pass the ammunition, boys. It’s business as usual.

-C.T.

The NRA today: going great guns

“RIFLEMEN ON the right,” author Robert Sherrill called them-but their love affair with firearms goes far beyond legitimate hunting rifles or target guns. They’re the National Rifle Association, 2.5 million strong, and the group has just one word for gun control: No. No. No. Repeat until election day.

The NRA bills itself as a sportsman’s lobby, the champion of law-abiding gun-owners, and so it is for millions of people. But along with its valid public services in the areas of gun safety and sport shooting, the NRA has polarized the gun debate and paralyzed legislators attempting to enact responsible gun control measures.

If money talks, the NRA can scream the ears off politicians who refuse to play its game. According to Ralph Nader’s study, Who Owns Congress?, the group has an $8 million budget and a staff of 250 full-time employees. The organization publishes two magazines and countless brochures to spread its gospel of the gun. Given a day’s notice, the NRA can bury a legislator’s desk in telegrams. When the Treasury Department under President Carter wanted to centralize records of gun sales, hoping to aid authorities in tracing guns used in crimes, the NRA went to its computer banks and bombarded Washington with 350,000 angry letters. Congress promptly caved in, cutting the $4.2 million the Treasury Department had allotted for the plan.

During the 1982 elections, as always, the NRA worked to elect senators, congressmen and state legislators who would hew to the party line of bumper-sticker logic: Guns don’t kill people, people kill people and When guns are outlawed, only outlaws will have guns. It’s the same old song, but the NRA never lacks for singers. In 1982, the gun lobby backed 170 Republicans and 87 Democrats on the federal level, with contributions to all endorsed candidates totaling $1.3 million. In contrast, gun control groups are mere striplings. The largest. Handgun Control Inc., could muster only $107,000 for federal candidates in 1982.

The NRA carries a big stick, but it has never spoken softly. An NRA board member, Rep. John Dingell of Michigan, denounced the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms (BATF) as “a jack-booted group of fascists who are… a shame and a disgrace to our country.” Dingell was appearing on an NRA documentary called It Can’t Happen Here, a half-hour diatribe ; against the group’s favorite bogyman. The NRA contends that the BATF, well-known as one of the government’s weakest agen-cies, persecutes innocent sportsmen and gun collectors.

The NRA’s current project is the passage of the McClure-Volkmer Bill, which gun control advocates say would effectively repeal the 1968 Gun Control Act. The bill provides for the mandatory sentencing of criminals who use a gun in a crime; perhaps this is the source of its appeal for at least a dozen Texas legislators listed as co-sponsors of the bill-among them Sens. John Tower and Lloyd Bentsen and Reps. Phil Gramm, Steve Bartlett and Ron Paul. But the bill could also make it legal to sell guns through the mail as long as the buyer and seller swear that they have met face-to-face. Barbara Lautman, a spokesman for Handgun Control Inc., says that there will be no way to prove that any such meeting took place. “This will allow criminals to get guns through the mail without any records kept,” Lautman says.

By some interpretations, McClure-Volk-mer would also increase the number of small handguns coming into the country. Current law forbids handgun imports unless they are “particularly suitable” for sporting purposes. McClure-Volkmer would delete the word “particularly,” thus making it more difficult to define the type of gun to be prohibited. And as if gun dealers don’t have it easy enough, the McClure-Volkmer Bill would force ATF agents to give “reasonable notice” before inspecting a dealer’s records and inventory. One warrantless inspection of a dealer each year would be permitted; after that, ATF agents would have to have warrants based on “reasonable cause.” With more than 170,000 licensed gun dealers already in business and more added every day, this revision would make federal enforcement of the 1968 Gun Control Act almost impossible.

The major gun control legislation now before Congress is the Kennedy-Rodino Handgun Crime Control Act, which would ban Saturday Night Specials and otherwise toughen federal laws regarding handguns. Its principal sponsor in the Senate is Edward Kennedy, a major target of the gun lobbies. In 1980, the NRA spent more than $165,000 to defeat Kennedy in his bid for the presidency.

Harlon Carter, the NRA’s chief executive officer, has never minced words about his group’s mission: “We will prevail until any politician who values his career won’t have anything to say against us,” he told The Dallas Morning News in 1981. Perhaps what’s good for the NRA is not so good for a democracy, but with that kind of money and that kind of fervor, is it any wonder that politicians rush to get on their bandwagon?

The legislators on gun control

Sen. Lloyd Bentsen: “I certainly want to reduce the crime rate, but I see no evidence that gun control and licensing would do the job. A better approach, I believe, is to get tough with those who use a gun in the commission of a crime.”

Sen. John Tower: “In my view, control of guns and gun ownership through legislation has never been a solution to rising crime rates. Those individuals who use guns in the commission of a crime will obtain guns whether or not there is federal or state legislation prohibiting or limiting ownership.”

Rep. Tom Vandergriff; D-26: Through an aide, Vandergriff said he would not comment on any legislation until he has seen it in its final form. “Mr. Vandergriff does not believe that national legislation will stop handgun crime,” the aide said. “With the sea of handguns already in circulation, is it really feasible that a federal law could take that many out of circulation, without seriously affecting the legitimate gun owner?”

Rep. John Bryant; D-5: “I don’t support gun control. It’s a local issue for the states to deal with. If you make a federal law about guns, who would enforce it? Who would arrest them, the FBI? But I do favor a ban on the manufacture and sale of the cheap Saturday Night Specials that melt at 1,000 degrees or less.”

Rep. Steve Bartlett; R-3: “The purpose of gun control ought to be to stop criminals from using guns in crime. The most direct and productive way to do that is through laws that require mandatory prison sentences for crimes with firearms.”

Rep. Martin Frost; D-24: “Rep. Frost has taken no position on any gun control legislation,” an aide to Frost said. “He does not favor any added federal legislation on the subject. If anything is going to be done, it should be reserved for the states.”

Rep. Phil Gramm; R-6: “Gun control laws don’t work. My frustration with gun control is that it is often presented as an alternative to stricter law enforcement. Firearms are a deterrent to crime. My 75-year-old mother has a little gun, and somebody breaking in has to weigh the possibility that she might shoot them.”

State Sen. Ike Harris; R-Dallas: “I’m opposed to gun control-to any form of it. Corny as it may sound, it’s the user and not the gun. Some gun dealers are probably too lax, but the Treasury Department licenses gun dealers, and I like it just the way it is. They’ve got enough restrictions.”

State Sen. Oscar Mauzy; D-Dallas: “I favor registration of handguns and anything else we can do to keep these Saturday Night Specials out of the hands of people who use them for illicit purposes, within the constitutional right to keep and bear arms. I’d also favor a cooling-off period of 48 to 72 hours. But I would not want to make it tougher to become a gun dealer. I’m philosophically opposed to licensing acts in general; they have a negative effect on competition. I was very enthusiastic about Paul Ragsdale’s gun bills, but you start talking about anything being done about the gun situation, and the NRA and the sportsmen’s clubs come off the wall. They see it as a giant conspiracy to keep them from skeet shooting.”

State Sen. John Leedom; R-Dallas: “I’m not in favor of gun control. I’m satisfied with the status quo. As for a waiting period, who would check the buyer out? The gun dealer would have to burden the police with this investigation. Cain and Abel didn’t have guns, but one of them killed the other. It’s the old Texas heritage, really. People want to protect themselves.”

State Rep. Steve Wolens; D-103: “The issue is not nagging at me, but it’s manifested in other ways, like with police killings. I see people murdered. But is that a handgun problem or a problem with people getting out of jail quickly and committing other crimes? As for handgun registration, I’d have to have a much better idea about whether this would keep deranged people or criminals from getting guns.”

State Rep. Bill Blanton; R-99: “I wouldn’t sponsor or co-sponsor any such bill. I’m for less regulation, letting people determine their own destinies. A waiting period does make a lot of sense, and it might be a good idea for gun dealers to report their sales. But it’s not a big thing with me at all. I don’t feel it’s an important issue.”

Get our weekly recap

Brings new meaning to the phrase Sunday Funday. No spam, ever.

Related Articles

Arts & Entertainment

DIFF Documentary City of Hate Reframes JFK’s Assassination Alongside Modern Dallas

Documentarian Quin Mathews revisited the topic in the wake of a number of tragedies that shared North Texas as their center.

By Austin Zook

Business

How Plug and Play in Frisco and McKinney Is Connecting DFW to a Global Innovation Circuit

The global innovation platform headquartered in Silicon Valley has launched accelerator programs in North Texas focused on sports tech, fintech and AI.

Arts & Entertainment

‘The Trouble is You Think You Have Time’: Paul Levatino on Bastards of Soul

A Q&A with the music-industry veteran and first-time feature director about his new documentary and the loss of a friend.

By Zac Crain