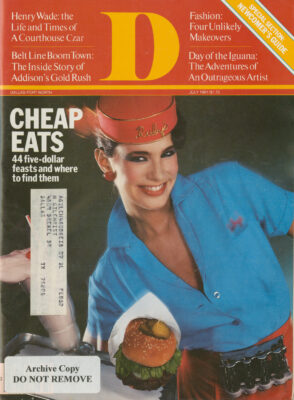

HE STILL REMEMBERS REBECCA. He has carried her memory in the back of his mind for 30 years. But he has never lost a minute’s sleep over her. At least that’s what he tells the others who still remember her. She deserved it. She deserved everything he tried to do to her and more. After all, he reasons, no one is above the law.

Rebecca Doswell presented a rather pathetic figure as she sat in the courtroom, hunched down in her wheelchair. She had the sympathy of the public. She had shot her husband, killed him on the parking lot of the social hot spot of 1951, the Melrose Hotel. And the high-budget defense team Rebecca Doswell was able to hire was doing an effective job of articulating her side of the story: self-defense. Mrs. Doswell had taken her husband’s life in defense of her own. And who was this hayseed prosecutor from Rockwall? Was he trying to make a name for himself by sending a rich woman to the penitentiary for life?

Henry Menasco Wade could hardly deny he was seduced by the challenge of it all. He’d only been elected district attorney of Dallas County a few months before the trial. And at age 37, he was still considered in some circles to be an ambitious but inexperienced upstart who had yet to prove himself. The sage old-timers were predicting the outcome before the trial had started: The defense team would chew up Henry Wade and spit him out on the courtroom floor.

If any doubts about Rebecca Doswell’s guilt entered the mind of the young prosecutor, his face never showed it as he marched back and forth in front of the jury box, reciting a litany of reasons why the people of the State of Texas should demand that this woman be sent to the state penitentiary in Huntsville for the rest of her natural life.

What any good prosecutor will tell you, of course, is that the real pros don’t give a tinker’s damn about what the people of the State of Texas want. All the courtroom histrionics, all the emotion that pours forth from the prosecutor as he preaches about why justice must be done, all the declarations about guilt and God and law are merely for the benefit of the jury. The real professional prosecutor assumes the defendant is guilty from the moment his name is typed on a case file. When a real prosecutor walks into the courtroom, he blocks out all the peripheral considerations and defines the judicial process in its true form: competition. If you are to be successful as a prosecutor, you know that it is a survival game-you win by making the defense lose. And if somebody goes to the electric chair as a by-product of that competition, so be it. They deserve it, or they wouldn’t be on trial in the first place. The survival a successful prosecutor must be concerned with is certainly not that of the defendant. It is his own.

Henry Wade would prevail in the courtroom because he quite obviously had a more keenly developed sense of survival than his opponents. He was tougher; he was quicker; he was more of a competitor. You could look at his resumé and see that. Valedictorian of his high school class. Star of his high school football team. President of the University of Texas law school graduating class that included the likes of John B. Connally. A competitor. A man who puts winning at the top of his list of priorities.

Henry Wade had his way with the jury charged with deciding Rebecca Doswell’s fate. They sentenced the woman to life in prison, just as Wade had asked.

Wade came away convinced that justice had been done. And more importantly, of course, Dallas County came away from the trial convinced that it had a tough and tenacious prosecutor. No matter that Governor Allan Shivers would later pardon Rebecca Doswell (who underwent six major operations for her illness as she waited in the county jail for transfer to the state penitentiary). No matter that Governor Shivers would say that “justice had not been served” when Henry Wade and the jury sent a woman like Mrs. Doswell to prison. Henry Wade’s conviction of Rebecca Doswell had shown the district attorney’s constituents that they had picked a winner, the type of man who is destined always to be a hero in a community like Dallas.

THE DOSWELL CASE WAS A REP-resentative beginning for Henry Wade’s career at the courthouse. In the three decades that have followed, Wade has established himself as a legend not only in Dallas County and in Texas, but in American jurisprudence as well. He and the men who work for him have obtained a quarter of a million convictions. In some years, 93 per cent of the defendants brought to trial by Wade’s office have been convicted. He has beaten the likes of Percy Foreman and Melvin Belli. He obtained a death sentence in his most famous prosecution of all, the case of Jack Ruby. He is the highest paid district attorney in the state. (Although at $53,000 a year, he is clearly not in his profession for the money. Were he in private practice in Dallas, he could conservatively be bringing in 10 times what he makes on the public payroll.) He has clearly had more impact on the legal community in Dallas than any other man. Of the 6000 attorneys practicing in the city, almost one-sixth started out as prosecutors in Henry Wade’s office. A more important statistic is this: Of the 14 district judges on the bench in Dallas County, 11 began as prosecutors in Wade’s office. He formulated their concepts of criminal justice. When a governor gets ready to appoint a judge to the bench in Dallas County, he starts the process with a phone call to Henry Wade. Most prosecutors pride themselves on their ability to pick juries. Wade takes it a step beyond that. He handpicks the judges.

And, in a system in which the defense attorneys and prosecutors usually come below the judges on the pecking order of influence and power, Wade obviously is above the gentlemen on the bench. Wade “grades” judges, keeping a list of their acquittals and convictions, publicly chastising those recalcitrant jurists who show a propensity toward being lenient to the men who stand before them in handcuffs and white coveralls. For decades Wade has run the county courthouse with his guile, his wit, and his toughness.

But now, for the first time in years, questions have surfaced about the man’s ability to hold the office. The judges and defense attorneys whisper in the hallways of the courthouse. Is he as tough as he used to be? Has he recovered from his recent heart attack? Is this man still the same tough cigar-chewing legend who was the law in Dallas County for all those years? Will he run again for office? The questions remain unanswered in the minds of many.

HENRY MENASCO WADE JR. learned at an early age how to wheel and deal to get himself noticed. He was born in 1914, one of 11 children born to Henry Menasco Wade Sr. (Family legend has it that Menasco is the name of an Indian princess who married a Wade somewhere down the line.) The senior Wade was a lawyer without a law degree and a sometime judge in Rock wall County. He settled in the 1890s on a farm near Squabble Creek, a community in northeast Rockwall County.

It’s hard to be born into the middle of a large family, especially when all five of your brothers are lawyers, too.

Henry Wade Jr. excelled from the start. He was a natural in Rockwall public schools, especially in English. (Wade says Charles Dickens is his favorite.) He was valedictorian of his class at Rockwall High School (class of 1932) and captain of the football team. As quarterback of the powerful 1931 Rockwall team, Wade was all-state, and in the fall of 1932, he left the Squabble Creek farm to attend the University of Texas and play football.

To this day, Wade carries with him the physique developed during all those football practices in Rockwall, although his weight is up about 25 pounds from the solid 175 he weighed as a high school senior. But the big man (he’s about 5 feet 11) didn’t stick with football very long.

After his sophomore year, Wade discovered he could make $35 more a month working as a student librarian than the $50 he could earn waiting tables like the rest of the football team. Thirty-five dollars was quite a bit of money in 1935 for a farm boy whose father could only afford to give him $85 to get to Austin in the first place. Henry Wade the football hero gave up the practice field and became Henry Wade the academician.

Friends joke that if it were not for that $35 a month, Tom Landry today might be out on the streets.

In 1936, Wade entered the University of Texas law school as a member of the famous depression-era class of 1938. Among his fellow class members was John Connally, who years later would help turn Henry Wade into a statewide power from the comfort of the Dallas County courthouse. Wade became president of his law school senior class and wrote for the law review.

At the same time, he continued to bring in his $85 a month as a student librarian. When he graduated in the spring of 1938, Wade took his bank account (about $1000) and went back to Rock wall. But Henry Wade didn’t want to hang around Rockwall. His ambition in law school had been to become an investigator with the Federal Bureau of Investigation. In the summer of 1938, so did a lot of young attorneys who couldn’t find law work in small cities like Kockwall.

Wade ran for county attorney of Rock-wall to hedge his bets in case J. Edgar Hoover denied his application. The election in the fall of 1938 was Wade’s first introduction to politics, and he was successful. It would be another eight years before Wade would run for office again. In the meantime, he would travel throughout the world as an FBI agent and an officer in the U.S. Navy, but that first political race infected him like a disease for which there is no cure.

Wade became an FBI special agent in 1940. As one of Hoover’s men, Wade spent time in Boston, Baltimore, Washington, and finally South America. One of the cases he worked on involved cracking a German spy ring in New York City at the beginning of World War II. It was later made into a Hollywood movie called The House on 92nd Street, although Wade insists the ring operated out of a house on 42nd Street. When the United States finally became embroiled in the second world war, Wade left the FBI and became a lieutenant junior grade and served aboard the Navy’s U.S.S. Hornet during the recapture of the Philippines from the Japanese. He later served on the U.S.S. Panamint during the Okinawa invasion.

After being discharged from the Navy in 1946, Wade went back to Rockwall with the intention of opening a law practice. But the little town was no longer big enough for the world traveler and battle-scarred veteran. The Flying Red Horse beckoned from the west, and Wade heeded the call.

In South America, Wade had done intelligence work for the FBI (the CIA had not been created yet). Back in Dallas in 1946, he began investigating again. He began a small practice and hung around the Old Red Courthouse, asking questions, observing the political scene, and deciding where and when to pitch his political tent.

“I didn’t have anything else to do at the time,” Wade joked several years ago. “I was just hanging out with some lawyer friends of mine, so I thought it might be a good thing to do.” Five men ran against incumbent District Attorney Will Wilson in the 1946 Democratic primary. Wade came in third. He quickly reassessed his position, threw his endorsement to the front-running incumbent, and elicited the dual promise from Wilson of an immediate job and support in his proposed 1950 race for district attorney. Those are promises that Wade has yet to make to any opponent or colleague.

Wade learned the business of prosecution from Wilson, returning the favor a quarter of a century later when he hired Wilson’s son directly out of the University of Texas law school. During the three years he served on Wilson’s staff, Wade did little to attract attention to himself. But at the end of 1949, he resigned from Wilson’s staff and made the district attorney keep his end of the bargain. Wilson wanted to run for attorney general anyway. (He later won.)

Wade announced his candidacy for district attorney March 11, 1950. The announcement that ran in both newspapers the next day featured a picture of a jowly but stern-faced young man who promised, “I shall do everything within my power to prosecute all racketeers and gamblers and send them to the penitentiary.” It’s a promise he’s kept and used to build the legend of Henry Wade.

Times certainly have changed for the district attorney since his first day in office in January 1951. From his plush office atop the sterile new courthouse, he can look down, away from the downtown skyscrapers, toward the Old Red Courthouse, where the legend was born and nurtured.

Wade rocked along as district attorney until 1961. It was a heady year for Democrats, especially in Texas, with a Democrat in the statehouse, a thoroughly Democratic state legislature, and a party-controlled state judiciary.

In Washington, a Texas Democrat was vice-president of the United States and another was speaker of the House of Representatives. It may seem farfetched now, but in August 1961, even Dallas County was safely in the fold of the Democratic party. A seemingly all-powerful triumvirate of politicians ruled the roost from the Old Red Courthouse.

The venerable Lew Sterrett controlled the county bureaucracy; legendary Bill Decker was a sheriff that no reporter lampooned in print, and the youngster of the bunch, Wade, then 47, reigned over the district attorney’s office.

Democratic stalwarts throughout the county were expecting favors from the White House in that Democratic summer of 1961. Wade, being the youngest of the county’s ruling troika, was also the most ambitious. He had friends in high places, and they owed him favors. Wade was ready to collect.

For three weeks during the summer of 1960, Wade had been in Los Angeles, lobbying delegates at the Democratic national convention for his old friend Lyndon Baines Johnson. Johnson, of course, did not receive the presidential nomination. But by August a year later, he was vice-president of the United States, and he had promised the ambitious DA that he would lobby to get Wade a seat on the federal bench.

A new judgeship had been created on the federal bench in Dallas, and the vice-president was promoting his old friend Henry Wade for the vacancy. The vice-president used his influence with another old friend, U.S. Senator Ralph Yarbor-ough, to have Wade top the list of Yarbor-ough’s candidates for the seat.

The two Dallas newspapers announced Wade’s appointment to the federal bench on August 13,1961, as if it were fact. They reported the top candidates to replace Wade as district attorney. The press had practically packed his bags for him and he had done nothing to discourage them. The Morning News reported that Wade’s appointment had been personally endorsed by Sam Rayburn, then speaker of the House of Representatives. Wade’s father had been a judge in Rockwall County for close to 20 years, and Rayburn was a personal friend of the Wade family.

But something went wrong. When Kennedy finally made the announcement in the fall, the federal judgeship went not to Wade, but to State District Judge Sarah T. Hughes. Wade lost out, his Washington friends told him, because Rayburn personally intervened on behalf of Judge Hughes, not Henry Wade.

Henry Wade was crushed. Outwardly, he plunged into his job as district attorney of Dallas County. Inwardly, though, Wade hasn’t forgotten the slight from the Democratic Party in 1961.

Year after year, election after election, appointment after appointment, Wade’s name has been mentioned in news articles. The party wants him to run for governor. He’s being considered for judge. They want him in Congress. But Wade has not taken the bait again. He has told close friends that after being passed over in 1961, he has wanted to do nothing but concentrate his efforts on “being the best district attorney I know how.”

He’s had no reason to seek higher office. As it is, Henry Wade is courted by governors; he is honored by judges; and he is wooed by defense attorneys. Sheriffs and police chiefs know he’s the power to be reckoned with in Dallas County.

Sitting behind his oversized mahogany desk on the seventh floor of the new Dallas County Courthouse, Wade has a panoramic view of downtown Dallas. When he looks out that window he can see offices where thousands of Dallas attorneys labor. He knows that in those offices are the 900 (of 6000 practicing attorneys in Dallas) who got their start with Henry Wade’s office. On the sixth floor below his spacious office work 14 criminal district judges. Wade knows that 11 of them used to be assistant district attorneys. Around him buzz more than 130 prosecutors. They all want to be rich, successful criminal attorneys or judges someday. And they know they can’t do it if Henry Wade doesn’t like them. There are dozens of lesser judges who want to become state, district, or federal judges. They, too, know they can’t ascend to a higher bench without Wade’s blessing.

Reporters court Wade, too. Not as often as they did 10 years ago, when both papers gave almost daily space to the pontifications of the district attorney. But they still question him about his power. Sitting behind the large desk, habitually chewing on his cigar, Henry Wade leans back in his big leather chair and laughs.

“I don’t know why you say all these things about me,” he says, as he spits another plug of juicy cigar into the jerry-rigged spittoon at the side of his desk. “I read things about me in the paper, and that’s all I know. I’m just a district attorney trying to do my job. Don’t give me the credit.”

Back in August 1961, Henry Wade may have been just another Texas district attorney. But that was before the national headlines of the assassination of John F. Kennedy, a block away from Henry Wade’s office in the Old Red Courthouse. That was before the controversial murder trial of Jack Ruby. That was before the two television movies about the trial in which professional actors portrayed the district attorney. That was before 1000-year sentences handed down by Dallas County juries and encouraged by the district attorney’s office were publicized and ridiculed in other parts of the country.

From the mid-Sixties to the mid-Seventies, Henry Wade was the most sought-after politician in the state. No one could touch the man’s power, and he wielded it deftly. Always, there was a polite word and a hearty laugh for the power brokers and politicians who came calling to Henry Wade’s offices, first at the Old Red Courthouse and then at the new marble-facade courthouse with the office designed to Henry Wade’s specifications. After the politicians were gone, though, came the Wade dispositions. Those who did not get his blessings rarely knew about it until months later (if they ever knew).

Beginning in the late Seventies, however, cracks began to appear in the legendary armor. Henry Wade is still the most powerful man in the county. He still has final say over which of the 15,000 cases filed every year will come to trial and which won’t. While he still decides about plea bargains in the most important cases handled by his offices, he no longer has the across-the-board power over the press, defense attorneys, and judges that he once possessed.

Henry Wade refused to be interviewed for this article. Unlike many other politicians, however, Wade was cordial in his refusal to be interviewed. “I don’t think I want to be involved in anything like that,” he said when I told him D Magazine wanted to profile him. “I’ve seen those profiles before, and it seems you just can’t write anything positive in a profile. It always has to be negative.” But he laughed about it, told a few jokes, and encouraged me to call him again at any time. It was 15 minutes before I realized that he had turned down an interview with me for the first time. As courthouse reporter for the Morning News, I had interviewed him dozens of times before.

But the press is only a minor irritation for Henry Wade these days. He good-naturedly scolds reporters from both Dallas papers for their courthouse coverage. They don’t spend enough ink covering the stiff sentences handed down to convicted murderers and drug dealers, he says. But the press doesn’t have an appreciable effect on the way his office is run. Judges and defense attorneys, however, do; and they no longer toe the Henry Wade line the way they once did.

During the past two years, Wade has been involved in a public shooting match with one county criminal judge (who handles misdemeanor cases) that was widely reported in the press. He has been investigated by a judge’s court of inquiry, and he has been reprimanded by the bar association. Most recently, he has been threatened with contempt of court by a civil judge, an act that would have been inconceivable a decade ago. Wade also has not personally prosecuted a case in almost 10 years, a fact that has been criticized by his opponents.

He still has a firm grip on his stable of 130 prosecutors and 50 investigators. More than two dozen were contacted about this article. Fifteen assistant district attorneys agreed to talk only after checking, “Are you sure the boss knows about this story?’” Even when they were told that he did, they didn’t want their names to appear in print.

Then there is the question of Henry Wade’s health. He suffered a minor heart attack in October 1979 and was hospitalized again months later for chest pains. It put in doubt his ability to run for an unprecedented ninth term as district attorney in 1982. Friends and foes alike predicted he would hand the office over to his trusted right-hand man and major domo, Douglas Mulder. But Mulder left the office unexpectedly early this year, and Wade’s friends say the district attorney is eager to run again. He refuses to say what he’s going to do.

“I won’t know until the time comes,” Wade said shortly after the election. “I may not want this job then anyway. Times have changed.”

But most courthouse observers believe that Wade and his office are running on the district attorney’s laurels. Although the office runs efficiently, like most large corporations, it doesn’t have the vigor of Wade’s early years – years when almost 40 per cent of the inmates at the Texas Department of Corrections were from Dallas County, years when Dallas County sent more inmates to death row than any other county, and years when drug offenders were given four-digit-year sentences.

In recent years, Wade has delegated more and more responsibility to his closest assistants. They have overseen the expansion of the office. They have personally prosecuted the most sensational, headline-grabbing cases. They also have competed against one another for Wade’s attention and for their share of the power.

Twenty years ago, Wade was personally in control of every facet of the office. Today, the district attorney’s office is split into different factions which at budget time resemble armed camps. Each faction is headed by a different assistant district attorney. None of them will admit it, but they are alt vying to be in the right position to take over the reigns when Wade finally decides to retire. The competitors include Jon Sparling, director of the white-collar crime section; Jim Burnham, who supervises the Dallas County Grand Jury; Norm Kinne, the chief assistant district attorney; and Winfield Scott, the diminutive chief misdemeanor prosecutor who runs his squad of law school recruits like the Marine Corps drill sergeant he once was.

With Mulder’s departure, the infighting has begun all over again. Most courthouse observers had assumed that Mulder, who joined Wade’s staff right out of law school in 1964, had been hand-picked by the district attorney to take his place. The most dramatic and effective prosecutor on the staff, Mulder-in looks and courtroom style – is a Wade clone. Like Wade, he has shocks of curly, dark hair. His perpetual tan and athletic build make him a dashing figure in the courtroom. He studied Wade’s style of cross-examination and was at his side during Wade’s last trial, the 1971 prosecution in Belton of Rene Guzman and Leonard Lopez for the murder of three sheriff’s deputies.

In the courtroom, Mulder is brilliant. He shows the same Jekyll/Hyde style that Wade first demonstrated in his prosecution of Rebecca Doswell.

Mulder had also assumed many of the routine office chores. He made hiring and firing decisions concerning attorneys as well as the clerical staff. It was Mulder, not Wade, who decided which attorneys would be promoted and which would be held back. Wade, in the meantime, was spending more time out of the office. There were important social engagements to attend, honorary awards to receive. There were his afternoon golf games at the Lakewood Country Club several times a week. Fridays were always half days, if Wade came in at all, so he could spend time hauling hay at his farm near Forney.

Wade was becoming insulated by Mulder, his personal secretary, and a series of chauffeurs who were hired on as investigators. Meanwhile, some of the other assistant district attorneys were also carving out their own personal kingdoms without the boss’ knowledge. Wade was livid when the Morning News reported that John Stauffer, then in charge of the misdemeanor prosecutors and now in private practice, was requiring his young staff members to buy tickets to a rally for County Commissioner Jim Tyson.

Later, when Scott replaced Stauffer, Wade was unaware that Scott, in the best Marine Corps tradition, had placed several of his male misdemeanor prosecutors on diets, forced others to get haircuts, and told his female assistants to wear dresses in the courtroom.

But Mulder knew. It came as quite a shock to members of the district attorney’s staff and to other courthouse observers when the first assistant stepped down in January to begin a practice in civil -not criminal -law. Both Wade and Mulder have publicly said the move was simply a desire by Mulder to stretch his legal skills in an area of the field in which he has no experience. But no one believes that. Mulder has told friends that he was frustrated with waiting for Wade to retire and that Wade, for his part, has found a new interest in controlling the office more thoroughly than before. The half-day vacations, the golf games, and the long lunches have all disappeared from Wade’s schedule. It’s been close to six months since Mulder departed Wade’s staff, but the vacancy still hasn’t been filled. More than a few of Wade’s remaining top assistants are worried about that vacant office. No one also seems to understand why a 67-year-old man like Wade, who seemed so bored after being elected to his eighth term, would suddenly develop a burning desire to serve a ninth term.

No one has a definite answer, and Wade won’t talk about it. He won’t even admit that the office is running any differently now than it ever was. But privately, many of his colleagues and adversaries believe the change occurred during Wade’s long recovery from his October 1979 heart attack – and was hastened by Doug Mulder’s behavior during the episode.

It was a typical Thursday morning, and some of the young lawyers thought it unusual that Wade didn’t show up for the going-away party of Rusty Ormesher. Ormesher was one of Wade’s top assistants, a fiery young attorney who boasted a perfect record during his 10 years with the district attorney’s office. He had never lost a case. The young lawyers, who rarely get to see Wade until they are promoted to the criminal district courts, thought for sure “the boss” would be there that day. But since Wade wasn’t spending much time in the office in those days anyway, they were more intrigued by the disappearance of Doug Mulder. Most of Wade’s top attorneys spent the morning joking and laughing with each other and Ormesher. There was a party atmosphere in the office.

It was a newspaper reporter who first cornered four of Wade’s top men in Ormesher’s office. He had heard from the police reporter that paramedics had taken Henry Wade from his Lakewood home on Velasco to Baylor University Medical Center the night before. Wade had been suffering from chest pains and had been placed in the intensive care unit, the paramedics said. The assistant district attorneys looked baffled. No one knew a thing. They thought Wade had had a golf date. Or was it that he had gone out to the farm early that week? It didn’t matter. All of them – even Mulder-said there was no truth to the paramedics’ wild story.

It wasn’t until later in the day that Baylor officials admitted that Wade was a patient in the hospital’s seventh-floor cardiac care unit.

Wade had been watching the last game of the 1979 World Series between the Pittsburgh Pirates and the Baltimore Orioles. Just as the Pirates went ahead in the sixth inning, the district attorney felt the first sharp chest pains. Thinking the pains were the by-product of the Italian food he had eaten earlier, Wade remained in front of his television set and watched the Pirates take the series. After the game, he told his wife of 30 years, Yvonne Hill-man Wade, about the pains. She began to worry, so she called fire department paramedics, despite her husband’s objections. She also called Doug Mulder, who was at home in bed.

Mulder, hoping that the pains were not a heart attack, didn’t tell anyone. Even after doctors that night diagnosed the pains as a “mild to severe heart attack,” Mulder kept quiet. He especially didn’t want Wade’s hospitalization to make front-page headlines. That’s why he didn’t tell his celebrating colleagues that Wade had been stricken. When questioned directly by the inquiring reporter about the heart attack, Mulder denied it. He said he didn’t know anything about Wade being in the hospital. He made the point clear: Living legends in Dallas County do not have heart attacks.

During his month in the hospital and 12 weeks as a cardiac outpatient, Wade went through obvious personal changes – changes that were reflected when he returned to the office in late November 1979. He had lost 25 pounds. He looked tanner and more fit than he had in years. The doctors had temporarily taken away his beloved chewed cigars. He started an exercise program. His first response to reporters when he returned to the office was, “I guess hauling hay wasn’t enough exercise after all.”

The public attacks against Wade by his opponents during his recuperation and shortly after he returned to office only seemed to strengthen the old man. Wade is fighting those political brush fires with renewed vigor, and seems more excited about his work than he has been in years.

The attacks started with the county criminal court judges, the 10 men whose courts oversee the prosecution of misdemeanor crimes. Eight of 10 misdemeanor cases filed in Dallas County each year are traffic-related charges. Those cases don’t make for the most exciting of dockets; most of the county criminal court judges are bored stiff and are just waiting for a vacancy on the state district court bench. (Until recently, lower court judges had to resign from the bench to challenge the district judges, and only once in recent years has an incumbent judge been defeated by a challenger.) Unlike the state district court bench – which is filled with so many former assistant district attorneys that defense attorneys jokingly call it “The Henry Wade School of Law” – there are only two county criminal court judges who once worked in Wade’s office. In public, Wade’s former assistants on the more prestigious state district bench are respectful, if not fearful, of their former boss. They should be. Most of them owe their jobs to the indulgence of the district attorney.

The lower court judges have no such allegiance, and more than two or three of them believe that Henry Wade is the only thing between them and a cushy seat on the state district bench. And they’re right. Every governor since Connally has consulted Wade before making appointments to vacancies on the state district bench. Even Wade admits that the governor will call him and ask about a certain candidate for a vacancy. There’s no guarantee the governor will go along with Wade’s recommendation, but no one Wade opposes has yet to be appointed to a seat on the bench.

“That judge is a liar and a thief, and you’d do well to check him out,” Wade once told a group of journalists about a particular misdemeanor judge he doesn’t like. “And he wants to be a district judge so bad he can taste it.” He won’t be as long as Henry Wade is around.

Open warfare between Wade and a group of the misdemeanor judges actually began before the district attorney’s heart attack. It began with Wade’s political and personal attacks-often carried through the newspapers – on county criminal court Judge Tom Price.

Price, a short, feisty, and temperamental lawyer who was 29 when he was elected to the bench in the mid-Seventies, had been one of Wade’s favorites for years. He moved cases quickly and had little backlog. At times he even challenged long-time Judge Ben Ellis for the sheer numbers of defendants he moved through the legal system. In 1977, however, Price’s statistics (the way Wade and his staff measure judicial performance) fell off. Wade didn’t like it. When Price didn’t respond to subtle hints Wade sent him through assistant district attorneys assigned to Price’s court, Wade resorted to stronger measures.

He initiated an investigation on charges that Price had held trials for several defendants-including the man who would become Price’s father-in-law -without prosecutors present. Wade leaked the information to several reporters and later sent the results of the “investigation” to the state judicial review board in Austin. As a result, Price was officially reprimanded by the state, although he was not censured or stripped of his robes as Wade had hoped.

Price retaliated a few months later when charges surfaced in a series of stories in the Morning News that Mulder had personally intervened in the misdemeanor cases of three friends to the benefit of the defendants. In one case, Mulder approached Price about postponing the drunk-driving trial of a prominent Mulder friend until the friend would be eligible for a suspended sentence. Price gleefully ran to the newspapers with the story. But no action was taken against Mulder.

Price and his allies on the county criminal court bench struck again in the summer of 1980, when County Criminal Court Judge Chuck Miller, a close friend of Tom Price, accused the district attorney’s office of “shopping” for more prosecution-oriented judges. The cases involved public lewdness charges filed against 10 individuals who were arrested while dancing at the Village Station, a gay disco on Cedar Springs.

In two trials in early May before Miller – with no juries present – the judge found the defendants not guilty of public lewd-ness. Miller was to try six more Village Station defendants after he returned from an out-of-town trip in the middle of May. While he was gone, Assistant District Attorney Bill Arnold dismissed the cases in Miller’s court and refiled them in the court of Ben Ellis, Henry Wade’s favorite misdemeanor judge.

“It was obvious to the state from all the circumstances of these two trials that Miller was going to find the remaining six defendants not guilty,” Chief Misdemeanor Prosecutor Winfield Scott said.

Miller was furious, especially concerning additional remarks by Scott that Miller had a personal prejudice against the police officers who filed the charges.

“This is a tremendous indication of the power the district attorney’s office wields over the judges and the entire justice system,” Miller said at the time. “All Henry Wade has to do now, by this logic, is make a mere accusation of prejudice or bias. By simply raising the issue either way, the DA should win.”

Price jumped on Miller’s bandwagon and called a court of inquiry to investigate the charges of “forum shopping” by the district attorney’s office. A special investigator was assigned by Price to look into the cases. The smell of Henry Wade’s blood was in the air, and the judges circled to take advantage of the situation. Harold Entz, another county criminal court judge who is not one of Wade’s favorites, appeared before the Dallas Bar Association’s board of directors asking for their support in the fight to have misdemeanor cases filed randomly. The battle lines were drawn, and Wade finally backed down and enforced reform of the case-filing system. But Wade has not forgotten the battle or its ringleaders.

“You can bet that at every opportunity Henry Wade is going to get Miller and Price and Entz, too,” said a former assistant district attorney who is now a criminal attorney. “If they ever want any favors from Henry Wade or anyone on his staff, they’d better forget it. You don’t challenge Henry Wade in the newspapers and get away with it.”

By the fall of 1980, it seemed like open season on the district attorney. During the fall elections, Wade personally endorsed Democrat incumbent state district judges John Mead, a former assistant district attorney, and Don Metcalfe, who was said to be leaning heavily toward joining the Republican party. Both were saved from the Republican siege and kept their seats on the state district bench, but Wade’s endorsement, the first of his career, did not go unnoticed.

On the day of the general elections, the board of governors of the Dallas County Criminal Bar Association issued a statement condemning Wade’s action: “Because of the pervasive power and prestige of the prosecutor’s office, the very endorsement of judges in judicial races raises the implication and specter of the undermining of judicial independence.”

Wade’s endorsement of the two incumbents was really nothing new, although last year’s endorsements were the first to appear on publicly released campaign letters. For years, however, Wade has let the judges in the Dallas County Courthouse know exactly whom he favors and whom he does not. The judges, for the most part, have been quick to curry his favor. If they don’t, they know that Henry Wade, with his armada of prosecutors (there are three permanently assigned to each felony and misdemeanor court) can make life very uncomfortable for them.

Wade keeps track of all the judges through discussions with the prosecutors assigned to each court. They work daily with the judge and can sense which judges are “prosecution-oriented” and which aren’t. But he also keeps tabs on the judiciary through a series of statistical reports that are collated by the district attorney’s office each month. The results are distributed for all the judges to see. Wade privately assesses each judge by what he sees on the monthly reports the same way a parent evaluates his child through a report card.

These judicial “report cards” measure the number of cases each court disposes of in a month, how many jury trials are held, how many trials go before the court and plea bargains are heard each month, and how many cases are filed in each court. To Henry Wade, the best indication of a judge’s superior performance is the number of cases he moves in a month. The more cases, the better the judge.

The judges pay strict attention to the reports. They begin to worry a little after several months of low case turnover. District court judges have been known to curse the gods for burdening them with a death penalty case because it can take weeks of full-day hearings to select a jury for such cases. When a judge is tied up with a case like that, it can be months before his statistics are back on track. One capital murder trial a year can throw a judge’s statistics off for the entire year.

Wade also has a strange pull over most of the criminal district court judges. Most of them used to work for the district attorney, and though they will deny it, it’s hard to forget the word according to Henry Wade.

“Any prosecutor coming up has to convince himself that if he’s prosecuting a case, then that guy’s guilty,” said one former prosecutor who has gone into civil law. “If you don’t do that, you can worry yourself into the old-age home about prosecuting the wrong guy. I couldn’t take it so I had to get out. The best prosecutors believe it completely.”

It’s usually the best prosecutors who become criminal district court judges. Rarely do “soft” assistants get Henry Wade’s recommendation when the governor calls. Although the able men who once served the district attorney and who are now judges would deny their bias, there are defense attorneys all over the city who would argue that once exposed, one never gets over being one of Henry Wade’s “mad-dog prosecutors.”

And it’s obvious that the man who has infected and inspired the “mad dogs” is still clearly the top dog himself. Deep inside he still is some part the farm kid from Squabble Creek who sincerely believes that if the police charge someone, that person is guilty.

Henry Wade established a dynasty atthe county courthouse years ago. He didso by proving he was tougher than thethousands of men he sent to prison,tougher than the hundreds of men whohave coveted his office over the years.Now he is out to prove he is still tougher.And it is clear to those who watch him thatthe dynasty is not over.

Henry Wade’s Box Score

HENRY WADE IS THE BEST-PAID district attorney in the State of Texas. Judging by his statistics alone, Wade deserves the money. There isn’t a prosecutor in the state, or the nation for that matter, who can claim as great a percentage of convictions or as small a case backlog as Henry Wade of Dallas County.

Throughout the years, local defense attorneys have formed, as a joke, an ad hoc organization called the “Seven Per Cent Club,” referring to the number of defense attorneys who manage to beat Wade and his crack prosecutors each year.

Recently, however, club members have joked that they should change the name of the organization to the “10 Per Cent Club,” given the growing number of acquittals returned by Dallas County juries year after year.

Still, Wade prides himself on having the best prosecution record of any district attorney in an urban county in Texas, a state nationally notorious for its toughness on defendants. According to county records, Tarrant County juries return guilty verdicts in only 80 per cent of all felonies filed in Tarrant County district court. The rate is lower still in Houston, where juries return “not guilty” verdicts in a full 25 per cent of cases.

Wade loves to brag to associates and reporters that his office’s record of success compares even more favorably to the conviction rates in places like Philadelphia, New York, and San Francisco, where district attorneys are lucky to convict 50 per cent of the defendants brought to trial in those cities.

Wade is shrewd in his strategies. Cases are rarely scheduled during the period between Thanksgiving and New Year’s Day because, Wade says, “Jurors are always in a forgiving mood during the holiday season.” It’s difficult in that month to get convictions, and it’s harder still to convince juries to return the hard-line prison sentences Henry Wade and his staff love so much.

Wade is worried, however, about the increase in the number of acquittals in recent years. His worst conviction rate in his three decades as district attorney was in 1979, when juries acquitted about 11 per cent of the 690 defendants brought to trial on felony charges that year. Last year, convictions were returned in “only” 90 per cent of the accused felons, and statistics for 1981 have yet to be compiled.

Wade has said an invasion of soft-hearted jurists from the North have watered down the stock of prosecution-oriented juries in Dallas County. He blamed the all-time high acquittal rate in 1979 on the Cullen Davis trial.

“It (the acquittal rate) is nothing you can put your finger on,” Wade says. “But you have a lot of people moving into this area from the North, where they always tend to favor the defense more than the prosecution.”

About the Davis trial, Wade adds, “If you’re on a jury and you look at this indigent, minority-type person and then you think about Cullen Davis, you’re naturally going to feel sorry for the poor person. Thank God that last Davis trial is over.”

Opposing attorneys have several theories as to why Wade’s prosecutionrecord is so spotless. They say that Wade controls the Dallas County grandjury. The grand jury is made of individuals selected quarterly by grand jurycommissioners, who are in turn chosen by the district judges. Most of thejudges are old colleagues of Henry Wade. Also, the district attorney’s officecontrols the flow of information to the grand jury. Only in rare instances aredefendants asked to testify. And defense attorneys are barred from thegrand jury’s seventh floor chambers. Defense attorneys say the grand jury isencouraged to no bill cases that the district attorney’s office does not feelthey can easily win. Wade scoffs at such excuses. – S.K.

How To Pick a Jury

MORE THAN 3000 JURIES ARE called in Dallas County each year, but not one of them is composed of a randomly selected sample of the defendant’s “peers.”

In fact, jury members are more often assembled on the basis of their race, sex, and income level than they are on their ability to render a fair and impartial verdict. In Henry Wade’s office, the adept-ness of a prosecutor in picking a jury is considered as important a skill as presenting a closing argument. There are written guidelines for jury selection with advice for beginning prosecutors:

1. When prosecuting a member of a minority race, it often works to thebenefit of the state to isolate a minority juror on an all-white panel. The ensuing pressure may cause the minority juror to bend over backwards for thestate in order to show the rest of the panel how fair he is.

2. It is said that people with Scandinavian and Germanic heritages makethe best state’s jurors, while Latins, Italians, Greeks, and Slavs tend to betoo emotional and are not good choices.

3. Chicanos often make good state’s jurors when trying a black defendant.

4. In some cases, it is advantageous to have a majority of women on thepanel. This is especially true in cases where children are the victims.

5. In a typical barroom killing, men will tend to justify the killing due tocircumstances under which it occurred – especially where the deceased had arough reputation -whereas women will be repelled by the violence and bemore receptive to conviction and punishment.

6. A prosecutor who lacks cross-cultural experiences, who feels uncomfortable around minorities or women, or who feels bias should avoid suchpeople as jurors.

7. Minority members from middle-class neighborhoods are all right, astheir values are solidly middle-class in most instances.

Wade says that his 130 assistants are not required to follow the guidelines set down in the 1980 Texas Prosecutors Trial Manual, and financed through the Texas District and County Attorneys Association.

Those guidelines, written by a female prosecutor in the Texas attorney general’s office, supplanted those laid down in the mid-Seventies by Jon Sparling, one of Wade’s top assistants. Sparling’s rules for jury selection, which have made him one of the most successful and ruthless attorneys in Wade’s office, were culled from his 1975 law enforcement seminar speech.

Excerpts from the speech were later included in a booklet financed through a grant from the Law Enforcement Assistance Administration, the same federal agency that financed the creation of the white collar crime section Sparling heads.

The Sparling quotes were used exclusively in the district attorney’s office until Dallas black leaders complained to county commissioners about the racist nature of some guidelines included in the booklets. It has since disappeared from the shelves of the district attorney’s office. Before it did, however, it drummed into the minds of impressionable young prosecutors the following tidbits:

1. “Minority races almost always sympathize with the defendant.”

2. “You are not looking for the free thinkers and flower children.”

3. “I don’t like women jurors because I can’t trust them.”

Wade said prosecutors aren’t encouraged to use any pat formula for jury selection. But in Wade’s office, the more convictions a young attorney can rack up, the faster he is promoted. Given the competitive nature of the DA’s office, they are willing to use any rule in the book to get ahead. – S.K.