In the quiet of her Grand Prairie home, Hilda Adams tried to rationalize the decision one last time. It had been the hardest thing she’d ever had to do. Barely 24 hours from now, with her reluctant consent, her 13-year-old foster son Gary would be committed to Terrell State Mental Hospital for 90 days. She and her husband Jesse finally had to admit that Gary’s problems were beyond their ability to cure them.

It had all happened so fast: A vandalism charge, juvenile court, the mental diagnostic center, a handful of boy’s homes, the suicide attempt, the doctors’ evaluations, mental illness court. She wondered what Gary thought about the whole business. He seemed so scared, confused; he was so insecure. She wondered how he’d fend for himself among 80 strange boys and girls. She wondered how he’d respond to the constant questions of strange adults in ominous white coats.

It’s for the best, she told herself. Terrell had doctors and nurses and programs to deal with kids like Gary; they were used to sudden outbursts of temper, near-catatonic trances, and fits of fantasy. They could straighten Gary out, she told herself. His problems couldn’t be that serious. He was really just like most other 13-year-old boys. Ninety days and he would be home – healthy, happy, normal.

Clara Kimball stared out the front window of her Oak Cliff cottage and wondered where it would all lead. A few weeks before, her 17-year-old stepgrand-son Chris had been committed to Terrell Hospital for 90 days of observation and treatment. In a way it had been a relief: Chris had not taken to adolescence well. It was as if another, violent self had exploded in him on his 16th birthday – fights at school; sudden, inexplicable outbursts at home; a scary sullenness. And of course, the murder. The police had never really pursued it, but they seemed convinced Chris was guilty of sexually abusing and strangling a five-year-old girl in Oak Cliff just a few months before.

Clara Kimball was a simple woman; she had no idea what to think of that. She loved Chris, so she had trouble even countenancing the thought that he could do something that horrible. But she knew that Chris, now a strapping young adult, was well beyond her control. Terrell was her only choice.

Darryl and Jerry Adams sat in the stark entryway of the Terrell Adolescent Center, peering anxiously down a long, shadowy corridor for a glimpse of their brother Gary. It was a Saturday, when many of the patients are allowed to visit their families, so the usually boisterous unit was comparatively quiet. Gary would be out in a minute, they’d been told; the attendant on duty was having trouble finding him.

Suddenly, there was a commotion down the corridor: Panicky voices, shuffling of feet, slamming of doors. An attendant hurried by and they asked him what had happened: A murder, he said. A patient had been found dead. His name was Gary Adams.

The press release was dry and terse: “An incident occurred at the Terrell State Hospital on Saturday, November 4, 1978, which resulted in the death of a hospital patient. The incident was immediately reported to the Terrell Police Department and to the Justice of the Peace as required by law. This incident is now under investigation by the appropriate law enforcement authorities.”

Hal Thome brushed back his thinning, sandy hair and considered the contents of the release. As attorney for Hilda and Jesse Adams, he’d been asked to find out, if possible, just how Gary had died while in the custody of the State of Texas. He and his investigator, Ray Whitley, had not dug up much, but they’d learned enough to know that the Terrell press release and the no-comments from the Mental Health and Mental Retardation spokesmen in Austin amounted to lies by omission.

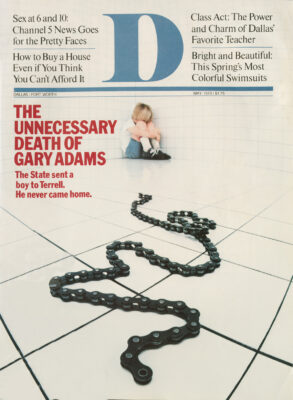

There were still too many unanswered questions about Gary’s death. The bare facts were that sometime between 1 and 4 p.m., Gary had been sexually assaulted and strangled with a bicycle chain in the room of 17-year-old Chris Nalley. Though no one on duty had heard or seen anything that afternoon, it stood to reason that the Nalley boy was the perpetrator: Sometime that afternoon, presumably following the crime, he’d broken out a window in an adjoining room and fled the hospital grounds. He’d been picked up by a hospital attendant on Highway 80, two miles from the hospital.

So much for what was known. What bothered Thorne was that the Nalley boy had been picked up at 3:30 – a full half hour before the crime was reported to the Terrell police; that at least one doctor had said the incident occurred at 2 p.m. – a full two hours before it was reported to the authorities; that Chris Nalley, with a record of violence, had been given a private room with a heavy wooden door and no observation window; that the lone attendant on duty had been stationed some 16 feet from Nalley’s room; and finally, that the autopsy had revealed that many of the bruises and contusions on Gary’s body were clearly the result of physical abuse several days before the murder.

Was it possible that Gary, who had always been the object of bullies, had been involved in some kind of ongoing physical confrontation with another patient – a confrontation that had gone either unnoticed or ignored by Adolescent Unit attendants and doctors?. Wasn’t there some means by which violent and passive patients could be segregated? Why had Gary, a tiny 13-year-old, been placed in a unit with larger, stronger adolescents? Why hadn’t he been placed in the adjoining children’s unit – which had an age range of 7 to 13? This was a mental hospital; obviously, fights and attempted sexual abuse were going to happen. Why had no one heard anything?

It was easy to expect too much of a state mental health facility, Thorne thought. Taxpayers wanted rehabilitation, but the bottom line dictated that about all a hospital like Terrell was capable of was minimal custodial care.

But this was not a matter of the relative quality of psychiatric care at Terrell; this was a question of basic safety and security. Hilda Adams had willingly signed over her son to the State of Texas. The State of Texas somehow had to be held accountable for Gary’s death. But how? Hal Thorne was a reasonable man. He understood what Terrell Superintendent Luis Cowley meant when he said “incidents of this kind are bound to happen.” But he also couldn’t help feeling that somehow the system had screwed up. For there was one simple fact: Neither Gary Van Adams nor Chris Colt Nalley ever belonged at Terrell in the first place.

Gary Adams never really had a chance. Born Gary Van Steeley in December, 1964, he was the product of an oppressive home. His mother, herself a mental patient, had been married and divorced five times by the time she was, 26; her frequent bouts with mental and physical illness made her incapable of supporting Gary and his younger brother, Jeffrey. Her drab apartment on Junius in East Dallas has no blankets or air conditioning, and only one bed.

Gary’s father was an alcoholic and also a mental patient. Case histories on the Adams boy allege Gary was physically abused by his father almost from infancy; often his father would use physical abuse to promote rivalry between Gary and Jeffrey – holding and striking Gary, while saying nice things to his younger brother. In 1969, Mrs. Steeley married for the fifth time, to a man she later alleged also abused Gary regularly. Following her fifth divorce, Mrs. Steeley signed voluntary placement waivers on Gary, handing him over to the Dallas County Welfare Department. He was immediately placed in the Dallas County Emergency Children’s Shelter for evaluation. Chief among the psychiatrist’s concerns was Mrs. Steeley’s allegation that Gary had tried to strangle his younger brother on several occasions; the situation had become so dangerous she had had to place Jeffrey in the custody of her mother.

The diagnostic testing on Gary was more encouraging than anyone expected: Gary, the report said, was a child “full of fantasy who was not necessarily schizophrenic.” His speech and language were intact; he seemed capable of “depth relationships.” He seemed sensitive to social norms; his anxiety was average. As for the murder attempts, the report characterized them as a “situational reaction of childhood. . . responding to a chaotic home and an inadequate mother.” The psychiatrist recommended that Gary be placed in a stable environment, preferably a foster home. No serious psychiatric care was recommended.

Gary was subsequently made a ward of the Dallas County Child Welfare Department, which placed him in the Jesse Adams Foster Home in Grand Prairie. As a foster child, Gary seemed capable of at least the appearance of normality. He took his share of the chores around the Adams’ household, and displayed a flair for cooking. He generally got along with the other children, Darryl and Jerry Adams. He was a bit mischievous and had a tendency to brood and be undemonstrative in traditionally emotional circumstances; and as he grew older, he began to run away from time to time. But Jesse and Hilda Adams had no reason to suspect Gary was anything more than a mild discipline problem. And a diagnostic summary later prepared by the Fort Worth State School interdisciplinary team stated that during his early years with Adamses, Gary became “a more secure child. . .beginning to relate to his peers and adults.”

In the mid-1970’s, however, Gary began to run away on an almost monthly basis; he became a habitual truant from school. When he did attend school, he invariably arrived home covered with lumps and bruises. Gary was always diminutive and frail, a result of his premature birth and a bout with pneumonia at three months. This, coupled with his shy, reclusive manner, made him an attractive target for schoolyard bullies. And because of his early exposure to physical abuse, he generally took the beatings passively, almost masochistically.

In September 1977, Gary, who had been legally adopted by the Adamses, vandalized a school bus at the county bus pool on Harry Hines. While his mother was at Parkland, he had sneaked across Harry Hines, found a bus with a key in the ignition, and accidentally backed it into another bus.

The case was placed in Judge Pat Mc-Clung’s state juvenile court. Mrs. Adams retained a young Grand Prairie lawyer named Hal Thorne. Thorne felt from the beginning that the accidental nature of the offense, not to mention Gary’s lack of a previous criminal record, suggested that the case should be dismissed, and Gary dealt with by some community-based outpatient psychological service. The judge agreed, and in January 1977, Gary was sent to the Fort Worth State School for diagnostic observation. The 14-page document remains the definitive profile of Gary Adams – except, of course, for the files at Terrell Hospital, which the hospital has refused to release to the Adams family, even in the wake of Gary’s murder.

In general, said the report prepared by five psychologists, Gary Adams was slightly backward intellectually, but not retarded. He was characterized as “immature,” prone to fights with other boys his age. The report emphasized that this antisocial behavior could probably be linked to the over-protective care of the Adamses. His 1Q was calculated at 90, “the lower end of the normal range.” One of the psychologists noted that Gary “may have a tendency to withdraw when confronted, as opposed to acting out his feelings in an aggressive manner.

“Gary does not appear to be dangerous to others,” she continued, “however, his tendency to withdraw and his difficulty in dealing with negative and conflicting situations and feelings could result in his doing harm to himself.” The clear implication was that Gary was not, at this point, suicidal, but that his shyness could lead him to be the butt of violent attacks by older, stronger, more aggressive children. The team’s verdict was that Gary continue in school and that he and his family receive outpatient counseling through the Dallas County Co-care Program. Meanwhile, Judge McClung agreed merely to probate Gary’s vandalism charge.

Barely a week later, Gary ran away from the Adamses again. This time he had to be sought and picked up by the police, who took him to the Dallas County Emergency Children’s Shelter. Gary was near-hysterical, and told the shelter intake worker that he was afraid of being beaten if he was returned home. The police report stated that Mrs. Adams had said she never wanted to see Gary again.

Gary became more reckless and aggressive at the Children’s Shelter. His Grand Prairie caseworker, Ann Somers, received repeated complaints that the boy was “very active and it was difficult to keep up with him.” Gary began nagging center employees for permission to smoke and to carry matches. A metal knife was also found in his possession.

Ann Somers decided to go visit Gary at the shelter. The problem was one she commonly faced as a Department of Human Resources caseworker: how to provide a disturbed juvenile with appropriate mental care without interfering with his home life. Parental rights had become a controversial issue for welfare departments across the nation. Like any welfare caseworker, Ann Somers was caught in the teeth of a bureaucratic Catch-22: Her reason for existence was to help troubled kids find a normal day-to-day life; but the extent to which she could act swiftly and surely to do so was limited by the individual’s and the family’s rights to privacy.

Public welfare and public mental health have become a labyrinthine bureaucracy. The Texas Department of Mental Health and Mental Retardation, with an annual budget of $332 million, is a maze of eight hospitals, 13 schools, 29 community centers, and numerous efforts that fall under the general heading of “programs.” An urban county like Dallas also has Department of Human Resources programs and county-level juvenile facilities. Even if Ann Somers could act swiftly and surely to help a child, she was required to negotiate a massive overlapping bureaucracy to do so.

On August 26, 1978, Ms. Somers met with Gary at the Children’s Shelter. She found Gary animated, somewhat clumsy (he spilled a Coke twice) and cranky: When she told him she wasn’t going to approve his smoking, he threatened to buy his own cigarettes and to obtain his own matches. The argument consumed some 35 minutes. Gary told her he was seeing his “shrink” regularly, though he added that he did not like therapy because “they only ask dumb questions and won’t tell me anything.”

Whatever was bothering Gary soon began to manifest itself in more obnoxious behavior. When his probation was over, he began to skip his therapy sessions; at the same time, the Adamses seemed confused about what to do with him: According to caseworker files, they too stopped going to parental therapy, and were difficult to contact concerning Gary’s problems. Ann Somers decided it was time to meet with Mrs. Adams.

The meeting with Mrs. Adams was confusing: The boy had obviously improved in the care of the Adamses; yet he made all manner of wild claims about their treatment of him. The foster parents obviously were of substantial enough means to support the child, seemed to be experienced and loving people and claimed to want the boy; yet they also seemed to be rigid about morality and strangely apathetic about Gary’s ultimate problems. A day after Ms. Somers met with Mrs. Adams, Mrs. Adams called and said that her husband felt Gary needed stricter discipline, and that “he needed to understand that limits are universal and that he will receive discipline in any placement.” Mrs. Adams said that her husband was willing to go to any length for Gary if Gary would just cooperate and go “even half way.”

Gary, however, was not willing to go that far. He still refused to return home. Ann Somers reluctantly set about the task of finding another place for him. Another foster home just wouldn’t work: It would only lead to more foster homes, more strange parents, more problems. Gary needed a permanent placement somewhere short of institutionalization.

She found a temporary spot for him at the Casa Boy’s Home in Dallas; within a week, he was asked to leave. Somehow the frail 13-year-old had become much more than a mild discipline problem: His fourth day at the shelter, he struck a girl in the stomach with a pool cue; a day later, he was caught drinking wine. Perplexed, Ann Somers rechecked Gary’s behavior record at the Emergency Shelter. What she found set in motion a rapid series of events that would lead Gary Adams to Terrell Hospital.

While Ann Somers had been led to believe Gary was a minor discipline problem at the shelter, nurses’ notes on the boy told a much different story. “Gary is very childish and always picking on the other kids,” reported one entry. “When they try to play with him he cries and gets all upset.” “He is very immature and uncooperative,” said another. “He has to be told several times what to do. Tonight he spit in Laura’s face – he said he did it because she hit him; I didn’t see her hit him.” And the final entry, one that left Ann Somers virtually speechless: “Gary moved to the holdover room because he would not be quiet. . .at approx. 10:45, I checked on Gary and went to the kitchen. When I returned Gary had tied a rope around his neck and attached the other end to the top bed. His feet weren’t touching the floor and his face was red. I started removing the rope, and Gary looked up and asked ’Why did you do that?’ “

Gary was returned to the Emergency Shelter while Ann Somers searched desperately for another placement. In a couple of days, Gary was in trouble again at the Shelter. Shelter director John Hoover told Ms. Somers Gary was “going bananas.” “Gary had been climbing under the table and swinging on the staircase where he was in danger of hurting himself and others,” her notes say. “When he sits Gary in a chair Gary will regress totally and withdraws into a fetal position. . . . Mr. Hoover also advised that Gary has been sharing his sexual fantasies with him regarding a girl he met at Casa. Mr. Hoover advised that Gary’s associations are totally inappropriate, that he will jump from talking about his mother beating him to liking Georgette because she has long legs and then back to his mother.

“I questioned Mr. Hoover regarding Gary’s homosexual acting out. Mr. Hoover advised that Gary had been found fondling another boy in the shower. He also advised on several occasions Gary had been found nude at the foot of another boy’s bed. Mr. Hoover has worked at Terrell Adolescent Unit. He advised that in his opinion Gary needed psychiatric intervention.”

Gary was sent back to MDC for additional testing. Psychiatric tests were performed by three doctors. Their conclusions were vague, but they were more than enough to get Gary Adams committed to Terrell. “Psychoneurosis with depression and schizoid traits,” said one. “Neurotic depression or psuedo-neurotic schizophrenia,” said the second. “Explosive personality” said the third.

The commitment process was now in motion, and despite Hilda Adams’ fears, there was no stopping it. Mr. Adams finally signed the placement sanction; court setting was made. On the word of one nurse, Gary had been classified as suicidal, “a danger to himself.” On the word of three doctors, he was “commit-able.” Gary Adams protested his commitment vehemently; but he had very little to say about it. The State of Texas had decided it knew what was best for him. At the time, no one could have imagined how wrong that assumption was.

Christopher Colt Nalley was born in September, 1961, and was regularly abused by his father and mother from infancy. Chris was one of seven children sired by three different fathers – two of whom were brothers. The Nalleys lived quietly in Waxahachie until 1966, when Child Welfare received an abuse complaint on the mother. A teacher of Chris’ had noticed severe bruising and scarring on the boy’s face and arms; the Nalley boy was something of a schoolyard brawler, but the injuries were unmistakably the result of parental abuse. Based on the complaint, Child Welfare obtained a temporary conservatorship of the boy. At the Children’s Shelter, Chris related his horrifying childhood to a series of social workers and psychiatrists.

According to caseworker notes, Mrs. Nalley was “sadistic and unpredictable. She hits the children with whatever is at hand, a board, a pan, a spatula, a shoe, her fist. She is given to rages which terrorize the children. The children’s behavior is totally controlled by her. They may not have friends at their house nor may they walk home with anyone. They are not allowed phone calls.” The documents go on to say that Chris was most often the object of his mother’s tantrums: A favorite disciplinary tactic was to force Chris to hold a broom handle while she beat his hands with a high-heeled shoe. Once she allegedly beat one of the boys with a broom handle until his arm was broken.

When Mrs. Nalley wasn’t around, Chris’ oldest brother ran the household with similar sadism. Chris’ three sisters were forced to have sexual relations with their brothers starting at age four; afternoons at the Nalley house were commonly spent in incestuous orgies, with the oldest brother directing things. On at least two occasions, Mrs. Nalley caught her children in sexual play and did not interfere.

It was clear even from Chris’ sketchy account of homelife in the Nalley family that serious State intervention was called for. But bureaucracies are not built to move swiftly or certainly: Chris was eventually returned to his home, and the Nalleys were enrolled in a county child abuse awareness program. Although the Nalleys stopped attending the program, and the abuse reports continued, Chris was not permanently extracted from his home until 1969.

By that time, it was too late. Chris’ early exposure to physical abuse and abnormal sexual relationships affected him deeply. Early psychological testing indicates the repeated beatings caused serious “organic brain syndrome”; though eight years old, he functioned with the intellectual and social skills of an infant. One too many blows on the head from his mother had rendered him seriously retarded. At the same time, Chris exhibited “profound affectional hunger” and “feelings of almost unbearable hurt and grief.” His principle problem was identified as a lack of trust in others. “Such distrust is quite understandable,” said one doctor’s report, “in view of his apparently chaotic upbringing; yet because he seems so badly scarred in this area, one wonders to what extent he can now fully profit from even the optimum nourishment. …” Chris was also diagnosed as a pathological liar and an extremely explosive, violent personality.

It seems clear in hindsight that Chris Nalley was no run-of-the-mill disturbed adolescent; even cursory case history research and psychological testing had revealed he was a potential danger to others and himself – a sure candidate for long-term institutionalization and treatment. But bureaucracies, by their nature, can only react. So Chris Nalley was allowed to go live with his stepgrandmoth-er, Clara Kimball, and to receive only basic outpatient psychological counseling.

Mrs. Kimball had always taken a special interest in Chris – to this day, in fact, she may be the only person the boy ever showed a genuine affection for. But she was an aging woman, who could not provide the disciplined household Chris needed. Freed from the bondage of his sadistic parents, and placed in a free, loving home, Chris Nalley was allowed to become a monster.

’ For the first few years in his new home, Chris was as close to normal as he had ever been. He was generally obedient and worked around the house without complaint. “He would work just for you to brag on him,” says Mrs. Kimball. He continued to be involved in almost daily fights at school and in the neighborhood; but most of them, according to Mrs. Kimball, were incited by others. Chris’ stuttering and slowness in class made him the butt of practical jokes and teasing. With the intellectual skills of an infant, Chris could strike back only with his fists.

As Chris grew from a boy into a man, his problems became more intense. By the time Mrs. Kimball received full conserva-torship of him in 1972, he was completely beyond her grasp. He often related wild fantasies to her, most of them with violent or sexual overtones; he often went to his room after school and fell into near-catatonic trances. He was involved in a brawl nearly every day. He was constantly being blamed for fights and vandalism in the neighborhood. He seemed to be having a good deal of trouble developing normal relationships with the opposite sex.

In 1976, as a psychologist had predicted, Chris “exploded inside.” Police arrested him for strangling, sexually abusing, and hanging a young girl near his home. The case was sent to Pat McClung’s juvenile court of hearing. Even the most heinous crime of violence can be handled outside the penal code as long as the perpetrator is a juvenile; it is the option of the DA’s office to certify the suspect as an adult and then to try him for the crime. But unless the individual is a repeat offender and the case against him is airtight, the DA’s office will generally let the juvenile judge handle the matter.

Juvenile judges have the most widely ranging authority of any bench in the state: In the case of criminal allegation, the judge may 1) decide to send the juvenile to a delinqency school for a prescribed period; 2) put him on probation, under the supervision of a probation officer; 3) return him to his parents’ supervision; or 4) order any one of a variety of psychological treatments, including institu-tionalization in Terrell Hospital.

McClung ordered a series of psychological tests to be performed on the Nalley boy. Meanwhile, Chris remained with his grandmother. The new series of tests revealed nothing new about Chris: Indeed, adolescence had apparently made his problem worse. Then, in July, 1977, Chris was implicated in a second sex crime: the rape and beating of a six-year-old girl.

This time McClung ordered specific testing for commitment to an institution. One of the tests was performed by Dr. John Holbrook, one of the most respected forensic psychiatrists in the nation. Holbrook’s conclusion was not surprising: “This young man needs to be institutionalized for long-term management. This conclusion is based on his admitted impulsive antisocial behavior in the past and the lack of probability that he will improve in the future. He functioned at the social level of a 7-year-old. It is my feeling that any State institution receiving this type of mental defective and emotionally disturbed individual would be appropriate, excluding Rusk State Hospital; where, in my opinion, this young man will be exposed to personal and sexual abuse, as well as an ongoing criminal education.”

The remainder of Holbrook’s test proved to be the most explicit account of Chris Nalley ever compiled; it also is a horrifying look at what can happen to the mind of an abused and neglected child.

Q: Are you going to school at the juvenile home?

A: Yeah.

Q: How do you like it over there?

A: Don’t like it. . .cause. . .cause. . .all the time all the kids ask me questions.

Q: What kind of questions?

A: How come I did what I did and everybody say I don’t want to be bothered. . . all the time I ask them to go on. . .they leave and some more boys come.

Q: Do they ever want to fight with you?

A: Yes.

Q: When you go to the gym, what kind of things do you do?

A: Watch the kids play basketball and that is all.

Q: Do you ever play?

A: Cause I don’t know how. . .I throw the ball back to them when the ball comes over there at me.

Q: Do you have any friends you play with?

A: I got a lot of friends. . . they always be gone.

Q: Where?

A: I don’t know. . .they always go play.

Q: The other kids pick on you a lot?

A: At school all the kids bother me. . .cause. . .I love art.

Q: What do you like to do most of all?

A: Most of all, I like to go outside and watch the kids play. Next thing I like is to draw.

Q: How many stars are in the flag?

A: Don’t know. . .never counted them. . .when flag moves eyeballs get mixed up.

Q: How many make a dozen?

A: Ten.

Q: How many make half a dozen?

A: Five.

Q: How many days in a week?

A: Five. . .is it? Or ten. . .I don’t know.

Q: How many days in a month?

A: Ten, is it?

Q: How many weeks in a month?

A: Two.

Q: What is today?

A: I don’t know.

Q: What month do you think it is?

A: Is it Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, I don’t know.

While Judge McCIung deliberated about Chris’ commitment, the attorney for the Nalley children, Tom McCorkle, moved that the other brothers and sisters be removed from the Nalley home. The move was a last ditch effort – the DA’s office, for some reason, had steadfastly refused to file criminal abuse charges against the Nalleys. In the course of the discovery and hearings that would eventually send the other Nalley children to a foster home, Mrs. Louisa Nalley’s deposition was taken.

Q: Did you get calls twice regarding the way Chris looked at school?

A: No.

Q: You never knew he had bruises and that that was why he was picked up from school?

A: I never knew because he dressed himself. He never did want me to dress him.

Q: Did you later find out that was the reason he was picked up?

A: Yes.

Q: And where were these located?

A: Just most anywhere. On his arm. One of his arms. I didn’t know anything about it. And then when 1 talked with Chris, I asked him about it. He said that he fall down from the swings in school. And I asked him how come you didn’t tell me, and he said I don’t know.

Q: Did you ever beat him?

A: No.

Q: Did you ever cause bruises on him?

A: No.

Q: Did you ever hit him in the head?

A: No.

Q: Was there ever a time when you hit him with a broomstick or have Ronnie do that?

A: No.

Q: Did you ever hit him with the heel of your shoe?

A: No. Those scars, I saw them after I got him back – I mean he started visiting me, I saw those scars. He didn’t have nothing on his face. He probably got them at where he was staying or somebody. But, he didn’t have anything.

Q: Are you a good mother?

A: The best I can.

Q: Well, is that good? You consider yourself a good mother?

A: Yes.

Q: And if Belinda and Chris were to say that you had, they would be lying; is that your testimony?

A: Yes.

Q: You never hit your children with force?

A: No. Just my hand.

The Nalley children were eventually ordered out of the custody of their parents; but not before McClung inadvertently epitomized the entire confusion of the juvenile system over the issue of parental rights and family privacy. In discussing his ruling, McClung is reported to have said: “Incest is some families’ way of showing affection.” The maximum security unit at Rusk Institute for the Criminally Insane had seemed to McClung to be the proper environment for the boy: He was a danger to himself and others, and obviously needed strict supervision and intense therapy. But getting an adolescent into Rusk is a lot easier said than done: Because it originated as an adult unit, the institute is reluctant to admit any juveniles; its adolescent unit, in fact, is only 4 years old and has only 30 beds. Second, Rusk officials look dimly on “potential psychopaths.” Though it is not explicitly stated in statute or Mental Health and Mental Retardation procedure, as a matter of course Rusk will admit only individuals with felony charges pending against them. Since Chris Nalley was a juvenile, and law enforcement authorities had refused to pursue the allegations against him, he was technically “unfit” for commitment to Rusk. McClung committed Chris Nalley to Terrell for 90 days of observation and treatment.

The indications are that Chris Nalley’s first few months at Terrell followed a pattern similar to his earlier institutionaliza-tion. He remained incorrigible, and the minimum security environment of the Adolescent Unit provided few corrective impulses. He often complained to his grandmother that he was blamed and punished for things he didn’t do; he became depressed, homesick. “Mama,” he told her, “they bug me. They don’t do any good to anyone.”

At the same time, he could dominate the other adolescents on the ward because of his size. A caseworker associated with Nalley says her impression was that Chris had his “run of the ward.” He was given a job carrying supplies, which gave him bulging biceps and forearms. Not much is known about his psychological testing and treatment, but it stands to reason that despite the severity of his problem, Chris Nalley was afforded the same treatment as the other patients were: Group therapy once a week, individual therapy twice a week, special education classes five days a week. Beyond that, he, like the other patients, was free to do pretty much as he pleased.

Mrs. Kimball says she is not aware whether Chris was involved in any regular brawling or violent activity at the unit; but it’s quite possible he was, since according to one former employee, “Things like that happen. Most of it goes unnoticed.” Further indication that Chris was too much for the Terrell Adolescent Unit to handle came in a statement a nurse made to Mrs. Kimball a few months after Chris was committed. “Chris will be out in a year,” she said blithely. “We have no place for him.”

Chris Nalley was recommended for permanent commitment on July 10th, 1978. The testimony presented at that proceeding is the best – in fact, the only – hard proof we have that Terrell was fully aware of Chris Nalley’s penchant for violent behavior and still kept him in a minimum security unit among younger, smaller boys and girls.

In Wayne Grant’s Kaufman County Court, two Terrell psychiatrists were asked their assessment of the Nalley boy. Dr. Bill Pederson, the director of clinical services in the Adolescent Unit at the time, was asked the following questions:

Q: In your opinion is this person mentally ill?

A: Yes.

Q: What is the diagnosis on this patient?

A: Sadism.

Q: In your opinion, is this person incompetent or competent at this time?

A: Incompetent, I suppose.

Q: In your opinion, should this person be hospitalized in a mental hospital for his/her own welfare and protection or for the protection of others?

A: Primarily for others.

Q: To your knowledge, has Chris exhibited any sadistic or violent behavior while he has been in the hospital?

A: Doing such things as – I know he choked someone on one occasion. It didn’t turn out to be serious damage done, but it is something to be concerned about.

Chris Nalley was indefinitely committed to the Terrell Adolescent Unit on the grounds that “it is necessary for the welfare and protection of others. . .”

In the wake of the Adams murder, Chris Nalley was sent on emergency placement to Rusk Institute for the Criminally Insane. He stayed there under observation until his indictment for the murder by a Kaufman County Grand Jury. The diagnostic conclusions of the Rusk staff are perplexing; they contradict every other psychiatric conclusion drawn on Chris Nalley during his 13 years in the MHMR system.

“The psychological examination revealed this patient to be functioning at a retarded level; however, he knows right from wrong and is able to talk to his lawyer and assist in his defense. On psychiatric evaluation, he is relevant, coherent, spontaneous and appropriate in thought and behavior. There is no looseness of associational content, no ideas of references and no affective disorder. He has poor impulse control, but this does not constitute insanity. His psychiatric diagnoses are: 1) Non-psychotic Organic Brain Syndrome due to head trauma, and 2) Anti-social personality.

“… there are no indications on our present examination to indicate that this patient had at the time of the alleged offense any mental disease that would render him incapable of knowing the difference between right and wrong or that would render him incapable of controlling his conduct to the requirements of the law.”

Who will take care of my child? Your child will never be left uncared for. Personnel are on duty 24 hours a day. Your child is assigned an individual therapist, a group therapist, a social worker, teachers, nurses, ward staff and a physician.

– from the Terrell Hospital orientation

guide.

It is in the nature of bureaucracies to perpetuate and protect themselves, so the actions of Terrell Hospital in the wake of Gary Adams’ murder are understandable, if indefensible. Following the public announcement on the incident, MHMR in Austin sent out the word to the hospital’s 1500 employees: Keep your lips buttoned – don’t talk to families, attorneys, the press; anyone quoted on the matter will be summarily fired. A measure of the hospital’s paranoia in the weeks following the crime was its treatment of the family of Gary Adams: Mrs. Adams was never formally contacted about the murder by the hospital; no letter of condolence was sent. A week after the crime, Gary was buried in Grand Prairie – at the family’s expense.

A week after the crime, MHMR Deputy Director Jim demons sent in four investigators to review the facts. The team was characterized as a kind of bureaucratic SWAT unit which would find and publish the truth, regardless of bureaucratic pressures. Their report, however, contained all the earmarks of a whitewash: “The verbal report I have,” said Clemons, “is that, in general, we found no evidence the hospital was negligent. The hospital was taking reasonable precautions and was following proper procedures. This probably couldn’t have been prevented unless we had round-the-clock one-to-one supervision on the youth, and our staffing just doesn’t allow that.”

Hospital superintendent Luis Cowley took a more aggressive tack. He said flatly that Chris Nalley was the type of patient who should never have been committed to Terrell. He added that the state presently had no appropriate maximum security treatment unit for disturbed adolescents and children. “This isn’t a prison we’re running. There are no bars on the window,” he said. He wound up by firing a salvo at Dallas juvenile judges, claiming that he has complained to them repeatedly about committing such patients, but that the flow of criminally insane individuals to the unit has not subsided.

Hal Thorne and Ray Whitley, though stymied by the no-comments of both police and hospital officials, managed to come up with a slightly different version of the incident – and what led to it.

●The hospital initially reported thatGary had been strangled with a “necklace”; the medical examiner’s reportstated flatly that it was a heavy chain,either from a bicycle or a leash of somekind.

●The time of the murder was placedbetween 1 and 4 p.m. At least one wardstaff member reported seeing Gary as lateas 2; a doctor on the ward confirmed that.Chris Nalley was not reported missing until 3:30; Gary Adams was not reportedmissing at all. The crime was not reportedto Terrell police until 4 p.m. If Nalley wasreported missing at 3:30, an attendantmust have observed the blood and disarray in his room and subsequentlydiscovered Gary’s body under the bed.Why did it take hospital officials half anhour to act? Why did it take them twohours to notice the absence of two patients, particularly the Nalley boy, whowas known as a security problem?

●No time of death was requested of themedical examiner’s office. Why?

●When the justice of the peace pronounced Gary dead sometime after four, the body was lying face up. A nurse on the ward, however, earlier reported finding the body face down. The police denied that the corpse had been tampered with, a serious transgression when a case goes before a jury. Had the body been moved and if so, why were the police denying it?

●Even cursory observation of the unitrevealed it was boisterous – radios blaring, children screaming. There was noway an act of violence in seclusion couldbe detected. Moreover, Chris Nalley hadbeen given a private room with a solidwooden door. Such an act obviouslycould neither be heard nor seen.

●While the hospital claimed 24-hoursupervision, visitors to the unit reportthat the nurses’ stations are often unmanned, or manned by a single individual who must oversee 30 patients or so. Budgetary limitations notwithstanding, why hadn’t the hospital beefed up its security, at least insofar as the Nalley boy was concerned?

●It was clear that hospital employeesknew of Nalley’s penchant for suddenand inexplicable violence: It was in hiscourt records and in his psychologicaldiagnosis. Why had they allowed him tobe recommitted to Terrell and why hadthey not supervised him more carefully?

●There was evidence the hospital staffwas also aware that Gary Adams was thesort who attracted bullies and that heallegedly had homosexual tendencies. Hiscaseworker had repeatedly contacted theunit staff about this problem; on one occasion, a staff therapist told her point-blank that they were aware of this andhad already noted that Gary had becomefriends with “another boy” and thismight become a problem.

No one at Terrell wanted the murder to happen. But government is rarely maliciously negligent; more often certain assumptions, procedures, and traditions add up to negligence. Because bureaucracies can only react, they must wait for crisis to accomplish even the simplest, most obvious reform. In the Gary Adams case, Terrell hospital was the victim of longstanding blind spots in our assumptions about public mental health.

The Terrell Hospital Adolescent Unit was created in 1963, in response to two important trends in public mental health care: One was the notion that mental patients should be segregated and treated according to age range, type of mental disorder, etc.; the other was the “Mental Retardation Facilities and Community Mental Health Centers Act of 1963” – a little-known piece of legislation that began mental health’s push to allow patients the maximum freedom and privacy while under care. Before this, juveniles had been arbitrarily mixed with adults, leading to frequent sexual abuse and worsening of the juveniles’ behavior through criminal education. The Terrell Adolescent Unit was formed by Cuban-born Dr. Emmanuel Balbona. In the early years, volunteer therapists were used on specific days of the week to provide adolescent care; the Terrell school system was gradually involved, and eventually a school was founded at the hospital. By 1966, adolescent admissions were growing at a rate of 30 percent per year – four times the overall growth rate of the hospital.

From the outset, Balbona intended the facility to be more progressive and more liberal in its policies than other units at the hospital. His feeling was that juvenile treatment also involved learning: The object of the unit should be to create the closest approximation of a home life possible. Hence, security has always been minimal in the unit: Doors leading into the unit are unlocked during the daylight hours; when out of school and therapy, patients are free to roam the facility; control of personal effects is lenient – if a child wanted to sneak a weapon into the unit, he could; sexual activity among patients was tolerated, unless it became a source of tension to other patients; patients were allowed to smoke and to have matches.

All of this led to some problems. Not long after the unit opened, a serious fire broke out, nearly destroying the entire building. It was the result of a patient playing with matches. In the late Sixties, two adolescents died of drug overdose. An employee at the time says drug abuse wasn’t out of hand, but it was frequent. Generally, he said, the doctors could sense abuse during their therapy sessions with the patients and put a stop to it. But as with sexual activity, occasional drug use was tolerated. As Balbona says in an article he wrote about the unit: “Each child was to have maximum latitude in reaching his own decisions, but this was to be accompanied by the responsibility for the consequences. The same principle was applied for the group structure as well, through a student and ward council that was responsible for making as many decisions as possible regarding the adolescents’ own living conditions.

While some of this led to friction with other sectors of the hospital – staff members commonly complained of “kids going behind the bushes” to have sex – the Adolescent Unit was generally a source of pride to Terrell. It was the only unit of its kind in the state and it stood at the vanguard of a national move toward more sophisticated adolescent care. Other parts of the hospital were often criticized – some of them even failed to meet federal inspection guidelines. But the adolescent unit was in tune with the times: The kids ran track and field, played football, took yoga classes; they worked with speech, art, music, and horticultural therapists. They went to school like normal kids and slept behind unlocked doors at night. By the early Seventies, the unit was claiming a 50 percent “success rate” for discharged juveniles.

Between 1972 and 1975, events happened that changed the unit’s image. A class action suit was filed in behalf of several inmates of the Texas Youth Council delinquency homes in Gainesville, Gatesville, and Mountain View. The allegations were sweeping: Uncleanliness, poor nutrition, unsafe conditions. Primarily, the parents of the inmates involved were worried about the system’s lax admissions policy. Because of the sharp increase in juvenile crime, and the inadequacy of the court system to deal with it, all manner of disturbed juveniles were being sent to minimum security TYC units. Psychopaths were arbitrarily mixed with mere brats or runaways, the suit alleged; and because the units were understaffed, security was non-existent.

The TYC suit had plenty of impact on its units: Within a year, every building in the system had a fresh coat of paint. But it also had troublesome implications for the Terrell Adolescent Unit. Because of Judge Wayne Justice’s federal court order, juvenile judges were afraid to send any juvenile with any previous record of psychiatric troubles to a TYC facility. He had to be dealt with by MHMR facilities. For the more hyperkinetic or violent kids, this simply meant Terrell. Soon the unit’s population had swelled to 80 beds; more significantly, the type of adolescent in the unit changed radically. During its first 10 years, the Adolescent Unit had been a receptacle for varied juvenile personality disorders: runaways, vandals, and plain ordinary brats made up the bulk of its patient population. Only five percent of the group suffered from organic brain syndrome; only 25 percent had any mental illness approaching psychosis.

With the advent of new TYC and juvenile court policies, however, tougher, more hardened kids began to seep into the unit. There was simply no place else to send them. By last year, psychotics made up 33 percent of Terrell’s population. Among the other two thirds, many of the vandals and runaways had been replaced by murderers and rapists. Overnight, the stylishly liberal environment of the unit had become a hazard rather than a source of pride. As Dr. Balbona says today, “An adolescent unit is like an atomic bomb. It reaches a point where you can handle so many kids with your staff. If you maybe add two more of a certain kind, then it explodes. It’s very important to remember that maybe at certain times you can take another acting-out sociopath because you have a relatively calm unit otherwise, but if there’s just one other child in there who might set off sparks in the kid – as it appears there was in this case – the whole place can blow up.”

The oddest thing about Terrell Hospital’s defensiveness about the Adams murder is that it was not entirely their fault. Indeed, Terrell was as much a victim of the system as Gary Adams – or Chris Nalley, for that matter – was. Still, the hospital continues to be uncooperative with even the most perfunctory inquiries concerning the case. During the preparation of this article, a dozen employees and former employees were contacted to discuss the unit and the case. A few cooperated; only one, Dr. Balbona, agreed to speak on the record. Dr. Mary Hargrave, the Adolescent Unit’s Director of Clinical Services, was cordial during a brief phone conversation. She called back the next day and left the message that she would “not be able to talk any further about the matters you were discussing.” An attendant on the ward, Jerome Halland, was similarly patient with the inquiries. But he finally simply said, “I would like to help you. There are some things that need to be aired and I hope they will be aired. But I just don’t feel comfortable talking about it now.” And Rick Strickland, the therapist who told Grand Prairie caseworker Ann Somers that Gary Adams had entered into a friendship with another boy that bore watching, simply said, “I can’t comment on that.”

“For fear of what?” he was asked.

“No fear about it. I’m just not going to talk about it.”

Cowley, Terrell’s superintendent, decided to communicate through his secretary. “The superintendent said to remind you that he has been ordered by central not to discuss the matter in any way,” she said.

Gary Adams never belonged in the Terrell Adolescent Unit. Even the judge who sent him there, Probate Judge Joe Ash-more, admits that now. At the worst, Gary should have been sent to the Terrell Children’s Unit, where his diminutive size and immature personality would not have attracted a Chris Nalley. More likely, he should have been dealt with at the community level. But because the commitment process is so haphazard, he was on his way to Terrell before anyone could raise an objection.

Gary’s commitment was based on the word of a single nurse who claimed he had attempted suicide. Ray Whitley subsequently investigated the “suicide attempt” and found that other Children’s Shelter personnel were not sure Gary’s feet were even off the ground when he was found with a rope around his neck. Mrs. Adams says that Gary commonly wrapped things around his chest or neck when playing; Dr. Holbrook says such behavior is not abnormal in the least. Moreover, Gary’s commitment was sealed on the word of three psychiatrists, one of whom could diagnose his problem only as an “explosive personality.”

Chris Nalley never belonged at Terrell either. He probably belonged at Rusk, among the criminally insane, from the beginning. Holbrook’s logic that he would only receive a further criminal education there is compelling; but finally, it cannot outweigh Chris Nalley’s potential danger to himself and others. Chris Nalley had been accused of, among other things, sexually mutilating two young girls and strangling one of them. Every psychiatrist who had ever examined him had concluded he was a danger to others and himself; two doctors who examined and observed him at Terrell diagnosed his singular problem as sadism. At least one staff member on Nalley’s adolescent unit ward was aware from the beginning that he had formed a troublesome relationship with another, weaker boy.

There’s a name mental health people use for boys like Gary Adams and Chris Nalley: They’re the patients who “fall between the cracks.” Bureaucracies pride themselves on providing a place for everyone; it is a way they perpetuate themselves – find a new problem, create a new program. Re-define the problem; refashion the program. Mental health bureaucracies have always been slightly different, though. The business of making mentally ill persons well – on limited tax dollars – has never inspired much experimentation. Hence, the mental health establishment has never really been prepared to handle everyone: They handle only the patients who meet the bureaucracy’s current definition of mentally ill; the others fall between the cracks.

The process starts at commitment. Currently, an allegedly insane adult can be temporarily committed on the word of a single doctor; juveniles require two recommendations for commitment. In some cases, that’s probably adequate; in others, it may not be. No one knows. Probate judges should be allowed more latitude in examining patients prior to commitment. Moreover, the psychiatric community should be given more clout – statutory if necessary – in commitment proceedings. At present, their capacity is purely advisory. The final medical decision is made by a judge. Dr. Holbrook, never one for piecemeal reform, says that urban counties should have an appointed board of psychiatrists that sit as the mental illness court in the area. The tribunal could be composed of three or five members, one of whom would be a judge. Their powers would be broad: They could order six, eight, or 10 tests on an individual, depending upon how complex his problem was; they would have the power to review the progress of patients and to order transition back into the community if warranted. A psychiatrist would have known that Gary Adams did not belong in the Terrell Adolescent Unit; a judge had no way of knowing.

To Judge Ashmore’s credit, he and Dr. Balbona have pioneered something of a stopgap reform in the area of screening and commitment. Within the past month, Ashmore has created a screening committee in his court, composed of a representative of local MHMR, a representative of Terrell, and a representative of the school district. The committee is charged with advising Ashmore on the type of commitment and treatment appropriate for each adolescent: The inclusion of the hospital in the process is crucial; until now, Terrell and the MI courts have been at odds with one another. Now the hospital can say at the point of commitment that it simply can’t handle a Chris Nalley.

The fact that Chris Nalley was given a clean bill of health at Rusk after the murder is symptomatic of a second problem: friction between MHMR hospitals and the courts. For example, if the staff at Terrell observes a potentially dangerous patient in one of its units, its only possible recourse is to take the case to its clinical committee. If that committee determines that the patient should not be at Terrell, but at Rusk, the patient is sent to the maximum security unit for testing. Rusk’s clinical committee then makes its determination. Depending upon current patient load, Rusk can arbitrarily send the patient back to Terrell. In that event, Terrell’s only choice is to repeat the process.

Obviously, MHMR needs to create a clinical “supercommittee” to settle such disputes in a dispassionate manner. The politicking between Rusk and Terrell is never going to be solved: Each is trying to please the commissioner with a solid bottom line. The patient gets the short end of the stick in the process. The statewide clinical committee could also be invested with the right to review discharges of patients – such as Rusk’s release of Chris Nalley. They should then have the right to take such discharge cases back to MI court for further adjudication.

All of that would help sort out in a more logical and orderly fashion the various kinds of mental patients the state cares for. But it wouldn’t solve the ultimate problem: that, at present, we have no maximum security unit for adolescents like Chris Nalley in the state. This is not a new idea at all: In fact, at least one state hospital system has had such a unit for four years. Oregon State Hospital in Salem created its secure treatment facility for adolescents with a federal grant of $2 million in 1975. The unit was allotted 50 beds – 25 for adolescents (age 13 to 17) and 25 for children (age 7 to 13). Five beds in each unit are reserved for “crisis” cases. The unit is heavily staffed: The ratio of security staff to patients is one to five; that excludes doctors and therapists. The physical plant features special security windows and surveillance features. Its doors are always locked.

An adolescent can be sent to the secure treatment center only on the recommendation of a special screening committee at the county level. The committee, similar to Ashmore’s in Dallas, is composed of a representative from the hospital, the local mental health unit, and the school district, and the judge. The vote of the committee, not the decree of the judge, is final. The criteria for admission are simple: Any patient with a background of suicidal, homicidal, or sexually deviate tendencies is committable, concrete evidence is required, but a criminal record is not. An individual like Chris Nalley, who is mistakenly sent to a minimum security unit, can be immediately transferred to one of the crisis beds in the secure treatment center. The unit, which claims a success rate of 78 percent, operates on a $1.4 million annual budget.

As Dr. Holbrook says, “There are only three functions that can be served by a mental health and corrections system. One is punishment, which our prisons take care of. One is treatment, which our hospitals take care of. The third is simply management, the individuals who fall in between the other two categories. We need to accept that we have some adolescents who require only management with little greater expectation. Mental health needs to admit to itself that there are some patients it simply can’t help. Otherwise, there’s no telling where we’ll wind up.”

One place we might wind up is in the 86th District Court of Kaufman County. That is where Chris Nalley’s sanity will be decided upon for at least the sixth time in his life. At present if the court finds him competent and sane – as Rusk Hospital suggests – he will stand trial for murder, and either go to prison for life or be set free. If he is declared insane, something very strange could happen. It’s unlikely a jury would remand him to the custody of his grandmother or any community-level facility; Rusk would seem an obvious placement, but the hospital has already indicated Chris Nalley is not quite insane enough for them. The last word on our mental health system is that Chris Nalley could well wind up back at Terrell.

Get our weekly recap

Brings new meaning to the phrase Sunday Funday. No spam, ever.

Related Articles

Arts & Entertainment

DIFF Documentary City of Hate Reframes JFK’s Assassination Alongside Modern Dallas

Documentarian Quin Mathews revisited the topic in the wake of a number of tragedies that shared North Texas as their center.

By Austin Zook

Business

How Plug and Play in Frisco and McKinney Is Connecting DFW to a Global Innovation Circuit

The global innovation platform headquartered in Silicon Valley has launched accelerator programs in North Texas focused on sports tech, fintech and AI.

Arts & Entertainment

‘The Trouble is You Think You Have Time’: Paul Levatino on Bastards of Soul

A Q&A with the music-industry veteran and first-time feature director about his new documentary and the loss of a friend.

By Zac Crain