James Zumberge looks like a university president. For that matter, James Zumberge looks like he could be president of anything – Harvard, General Motors, the United States. But he is in fact the president of Southern Methodist University. Tall, white-haired, handsome in a lean, somewhat ascetic way, he speaks with baritone assurance.

Zumberge ushers a guest into a huge, rather austere room in Perkins Administration Building. The guest is seated in one of two great leather armchairs, more womb than chair, but Zumberge doesn’t sit in the other one. He crosses the room to his desk, a great carved antique, and sits behind it. Behind the desk is a map – not a map of the campus, or Dallas, or the United States, but a map of Greenland. The president of SMU is a distinguished geologist; there is a Cape Zumberge in Antarctica named after him.

James Zumberge does not joke, does not break the ice with jovial chit-chat, and others’ attempts at humor are met with a cool smile or an icy look that says “we are not amused.”

James Zumberge is clearly in charge of things at SMU.

But why would anyone want to be? That was the question apparently asked last year by Otis Singletary of the University of Kentucky and Frank Rhodes of the University of Michigan, both front runners for the SMU presidency. Singletary and Rhodes paid personal visits to the campus, and after looking things over, quickly pulled out of the competition, leaving the SMU presidential search committee without a serious prospect in sight.

Singletary and Rhodes saw the obvious – that SMU was in a tumultuous state, more fit for a gladiator than an educator. Paul Hardin had just been fired by the Board of Governors, which was fighting with its companion Board of Trustees. The football program was losing both on the field and in NCAA investigations. Worst of all, SMU had accumulated a $5 million deficit. Raising money for a private university isn’t easy, even if you can offer to name buildings for the donors. But how do you charm donors into paying off a $5 million bank debt?

For one reason or another, James Zumberge seemed to think the situation was “challenging,” so he offered to leave the chancellorship of the University of Nebraska, home of fine football and guaranteed state funding. If Zumberge failed at SMU, it would be understandable, but if he succeeded, it would be heroic – the capstone of his academic career.

Southern Methodist University, says the old insiders’ joke, is neither Southern nor Methodist nor a university. After all, more students come to it from Illinois than from any other state except Texas, and more than half of its students come from outside Texas. And although its Board of Trustees is required by charter to have a majority of Methodists (including all of the bishops of the South Central Jurisdiction), the real power is vested in the Board of Governors which is made up of more businessmen than bishops.

SMU, founded in 1911, remained a small, church-related college with little national recognition in its first 30 years. After World War II it became a football power, thanks to Doak Walker and Kyle Rote, and an institution with some pretentions to national academic status. It was a middle-sized private institution with a few colorful professors, a nice spacious campus in a pleasant urban setting, and lots of fraternities and sororities.

Willis Tate was a big part of SMU’s recent past – as president of SMU from 1954 to 1972 and chancellor until this year. An affable former SMU football player, with two degrees from the school and honorary doctorates from several small, mostly Methodist-related colleges and universities, Tate was no scholar, but he had a good sense of what sort of place a university should be, and he held on to that vision sometimes in the face of strong pressures from the Dallas community. He worked effectively to maintain SMU’s outward image of affluence, and its national reputation as a “good” school. He helped attract some important donors – the most glamorous being Bob Hope, who gave SMU both money and celebrity.

But Tate has been criticized for not providing coordinated leadership. He was too accessible, some faculty members say; aggressive deans and department chairmen won commitments from him that might have been turned down or modified if they had gone through administrative channels. Many say he spent too much money on “cosmetics,” on manicured lawns and showy offices, and not enough ensuring that SMU was on an even course toward financial stability and academic excellence.

When Tate announced his plans to retire in the early Seventies, the Board of Trustees named as president Paul Hardin, who came to SMU from small, Methodist-related Wofford College in South Carolina. Hardin was young, handsome and aggressive. He delighted the media but he had a streak of brashness that sometimes tripped him up in private conversation. One influential SMU graduate recalls meeting Hardin and introducing himself by saying “I’m an SMU alumni.” “No you’re not,” Hardin snapped back. “You’re an alumnus.” Relations between the two never recovered. In the end, it seemed, Hardin’s real problem was not being able to cope with the administrative size of SMU, the complicated split responsibility between himself and chancellor Tate, and the discontent of the most influential members of the Board of Governors with his performance. He resigned in June, 1974.

When Zumberge accepted the job at SMU last summer, he must have known what he would be walking into. From all reports, he named his own terms when he took the job. (He turned down the offer of a house on Lakeside Drive.) He left a position at the University of Nebraska, where he was chancellor in a system with a president. Zumberge reportedly was unhappy with the division of power, just as his troubled predecessor at SMU, Paul Hardin, had been unhappy with the necessity of sharing his power with chancellor Willis Tate. Tate has now officially retired and assumed the title of chancellor emeritus.

The two-year Hardin interregnum at SMU did little to change the character of the school. But in less than a year, Zumberge has managed to make some major visible changes at SMU. He is, after all, SMU’s first real scholar-president, the author of 10 books and over a hundred scholarly articles, and in addition to the cape in Antarctica, a library at Grand Valley State College in Michigan has been named for him. One of the first things he did on arriving at SMU was to send copies of his bibliography to the faculty – a signal from the top that SMU is going to be an institution increasingly concerned with the visible results of scholarship, namely, lots of publications.

Then he began an administrative restructuring that has been swift and, some say, ruthless. (One former v.p. who was relieved of his job will be teaching freshman English this fall.) He has reduced the number of vice presidents from six to four and has added an executive assistant, John J. Stephens III. One faculty member quipped to Zumberge that Stephens’ job was to be “a nice Haldeman.” Zumberge was not amused.

And he is about to initiate the biggest fund-raising drive in SMU’s history, designed to bring its endowment up to where it should be. Zumberge says candidly that SMU’s endowment is too small by half. It now has, he says, a book value of about $60 million, so that would suggest the fund-raising drive will aim for at least that amount. Several sources say it could go as high as $100 million.

And, most surprisingly of all, Zumberge has everyone – administrators, deans, even members of the Boards of Governors and Trustees – chiming in with a distinct party line about the future of SMU. In the past, especially in the last few years, SMU has hardly pulled together at all.

Publish or Perish

To enforce his emphasis on big-time scholarship at SMU, Zumberge will need the support of the academic deans. Fortunately for him, he has a good chance to shape a strong team of deans, since virtually every school at SMU involved in undergraduate education – humanities and sciences, engineering, business and fine arts – either has a new dean or is seeking one. Engineering and arts are still searching for replacements for deans who have resigned or retired. Business has a new dean, Alan Coleman, Stanford-educated, and formerly a professor at Harvard’s business school. Lee McAlester, a Yale Ph.D. who taught at Yale for several years, became dean of humanities and sciences in 1974. It is no accident that Coleman and McAlester have been associated with major American universities. As one longstanding administrator puts it, “At last we have people at the top who have been to real universities and know what they’re like.”

A stiff “publish or perish” policy has been initiated for the first time at SMU. The school’s tenure policy has been tightened and the axe has begun to fall frequently and resoundingly as assistant professors come up for sixth-year review. In one department, for example, eight assistant professors have come up for review in the past four years; only three survived the cut. Both of these policies put SMU in a better position to recruit faculty from prestigious institutions. Ten years ago SMU was competing with Stanford, Columbia, Yale and Harvard for younger faculty – and losing. But economic retrenchment has hit most universities and Stanford and the others are no longer hiring. So young scholars who once would have turned up their noses at the prospect of teaching at schools like SMU are now eagerly inundating department chairmen with more applications than beleaguered secretaries can even acknowledge.

How Firm Are the Foundations?

The impending fund-raising campaign represents a major change of emphasis in SMU practice. Except for the annual Sustentation Drive, which underwrites the university’s operating expenses, most financial support for the past 10 years has been solicited for specific schools, departments or functions (like football). The new program will involve a massive re-educating of donors, everyone admits. Fund-raising in the Sixties was handled by foundations set up for the support of specific schools – business, engineering and fine arts in particular. The roster of names on the foundation for the business school, for example, is a staggering Who’s Who in Dallas Business – men like Will Caruth, W.W. Clements, Michael Collins, Trammell Crow, Robert Folsom, Ray Hunt, Herman Lay. Henry S. Miller Jr., John D. Murchi-son, Raymond Nasher, Robert Stewart and Morris Zale, among others. The other foundations have equally impressive members. With supporters like these, small wonder that SMU’s professional schools experienced rapid and impressive growth. The School of the Arts, for example, began operations in 1968. Thanks largely to the philanthropy of Algur Meadows and an impressive body of other patrons, it already has established professional programs in theater and dance that rank with the nation’s best and has formed a distinguished art faculty around one of the country’s finest collections of Spanish paintings.

But the School of Humanities and Sciences, the largest in the university, and the one most concerned with traditional liberal education, has no foundation supporting it. Its funds come largely from tuition paid by its students – and more and more students are being lured away from H&S by the glamor of the professional schools. There has been less and less money in H&S for development of programs, recruitment of faculty, laboratory materials and library books, sabbatical leaves, faculty raises and research assistance – all those things that a strong academic program depends on. Various reasons have been advanced for H&S’s failure to establish a group of patrons – the most obvious being that there is no ready-made constituency to serve a multifarious body that includes departments of English, philosophy, foreign languages, psychology, anthropology, math, physics, and so on. Business schools obviously attract businessman patrons, theology schools supporters of the church, engineering the major industrialists, and the fine arts that core of philanthropists that traditionally endow museums and theaters and music organizations. But who do you ask for money to support research on Icelandic sagas or bushmen of the Kalahari?

Many members of SMU’s faculty and administration now feel that the foundation approach to money-raising has outlived its usefulness, if indeed it wasn’t a distinct mistake to begin with. Some think it prevented SMU from increasing its endowment -J funds that the university could administer where it saw fit. And there have been a few instances when important backers appear to have overstepped the bounds in exerting influence on the internal workings of individual schools. The case of Patrick Canavan is frequently cited as an instance of patrons meddling in academic matters, though as is usual in such cases, no one will go on record admitting influence and naming names. Canavan, an innovative scholar and teacher in the field of organizational behavior, was hired as an assistant professor in the business school in 1970. Canavan’s personal behavior, however, his long hair and jeans and the rumor that he had no fixed address but had converted his office in the Fincher Building into an apartment, was not exactly what the conservative backers of the school expected of an SMU professor. So barely a month after the fall semester began at SMU, Canavan was given a paid leave of absence from the university, with the understanding that his contract would not be renewed when the leave ended.

The Canavan case might have led to censure of the SMU School of Business by the American Association of University Professors, the watchdog organization that oversees professional standards on academic freedom, but Canavan was not interested in being at the center of academic turmoil and told the AAUP he had no wish to contest the dismissal. Whatever the real degree of involvement of the foundation members may have been, they were the immediate suspects in the Canavan case, and concern among the faculty about SMU’s ability to function independently of the men who paid its bills was widespread.

The foundation system was predicated on what one former administrator describes as an “islands of excellence” approach. The idea, he says, was to allow heavy donations for specific projects with the belief that a few outstanding schools or departments at the university would begin to attract national attention, outstanding faculty, and first-rate students. Then, he says, the money would begin to flow throughout the university wherever it was needed. The “islands of excellence” approach has been abandoned prematurely, he believes, and he points to the reputation of departments like theater and dance as areas where SMU has come a long way in an astonishingly short time. Now, he believes, SMU is trying to raise itself by its bootstraps, and if it doesn’t get the kind of money it’s aiming for it will simply raise itself to a higher level of mediocrity.

The Stanford of the Southwest?

There is a model for the kind of progress SMU wants to make. Stanford University was founded in 1885, about 30 years before SMU, and it muddled along, overshadowed by the nearby University of California at Berkeley, until the Fifties, when it suddenly shot to prominence as a first-rate national institution. For its fund-raising program, SMU has hired the consulting firm, Kersting Brown of New York, that was centrally involved in Stanford’s emergence by helping raise $100 million, aided by a matching grant from the Ford Foundation. Kersting Brown also recently helped raise $30 million for Rice.

Can SMU repeat the Stanford success story? Everyone in the SMU administration seems to think so, and they echo one another with a striking party line. Zumberge articulates it this way: “SMU is one of the youngest universities of its size, and it’s moved a long way in a short time. It’s not yet up to the standards of Duke or Northwestern, but it’s the strongest private university in the Southwest.” (Zumberge excludes Rice from this assessment because of its size and its emphasis on the sciences.) “SMU’s law school has a fine reputation, the Perkins School of Theology is in the top 10, the anthropology department is one of the top 20, economics is in the top 15, and the programs in theater and dance in the top 12.” Zumberge thinks SMU will emerge as a national institution because of its location. “SMU and Dallas have grown up together, and if Dallas is going to continue to achieve its potential, it will need SMU to do so. No major metropolitan area in the United States has achieved its status without at least one great private university in its midst. SMU has great unfulfilled potential – unfulfilled because of its youth.”

Business school Dean Alan Coleman says much the same thing, though he translates Zumberge’s vision into more pragmatic terms. Coleman has been a businessman as well as a professor; he came to SMU after heading up some huge vacation-recreation developments in California. His office, like most businessmen’s offices, includes a framed motto – Coleman’s is “The Golden Rule: Those who have the gold make the rules.” He says that SMU’s youth, the fact that it’s just moving into its third generation, is important for fund-raising, since its graduates are just coming into big-time wealth and are ripe for contributions. The time is right, Coleman thinks, for a major drive for big money. And Coleman echoes Zumberge, practically verbatim, about the fact that every great American city has a great private university. Coleman believes that Dallas’ position at the midpoint of what is variously called the “Southern Rim” or the “Sunbelt” gives SMU a unique position for recruiting faculty, students and potential donors. As the line goes, this is where the action is going to be, so come on down and be part of it.

The University of NorthPark

But does SMU really know what kind of university it wants to be? It’s too big to be a liberal arts college like the University of Dallas and too deeply involved in undergraduate education to be a graduate research university like the University of Texas at Dallas.

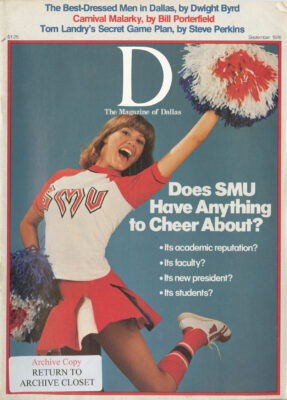

The campus at SMU is, as it has always been, peaceful. The burning issues of the past school year were whether beer should be served in the student center and whether three of the nine cheerleaders had to belong to minorities.

SMU’s comparative peace and stability in the late Sixties didn’t hurt its image as a safe school. Parents from the suburbs of Chicago, St. Louis and Kansas City were reassured that there was at least one college that hadn’t lost its head. Their sons and daughters were reassured that the school wasn’t out in the sticks like Sewanee or Sweet Briar, that SMU students looked as easy-going as themselves, and that academic pressures seemed to be pleasantly in proportion with having a good time. As one faculty member observes, the students come to SMU instead of Duke or Northwestern because of NorthPark. “Their parents send them here with strict instructions not to go downtown – who knows what evils lurk there – but to go to NorthPark for anything they need.”

Not all SMU students are the “partying numbskulls” one faculty member calls them. But almost everyone admits that the quality of the students is a problem – even students complain about the homogeneity of the student body, the lack of intellectual excitement and diversity. Virtually the only undergraduates who are attracted to SMU because of its programs are those in theater and dance, where the professional training is superb. And all too soon these students find themselves devoting most of their time to rehearsals and practice, so they contribute little to the life outside the Owen Arts Center. Otherwise, one SMU administrator admits, SMU is usually a “second choice” university for students who can’t get into Stanford or Northwestern, and it probably attracts no more top quality students than Texas Tech or A&M, though on the whole it is more selective than the state schools.

Walter Snickenberger, brought in from Cornell by Zumberge as vice president for student affairs, will be concerned with student recruitment. He says, quite simply, “It takes money.” Another administrator says flatly, “We need to buy top students. There’s no point in doing what we have been doing – bringing in highly qualified faculty from Harvard, Yale and so on – if all they have got to work with is students like the ones we’ve got now.” Financial aid is limited at SMU, and a large portion of what exists is budgeted for athletic scholarships. To increase financial aid – and Zumberge has pledged a proportional increase in financial aid for every increase in tuition – SMU needs more endowment income and alumni gifts. One administrator estimates that only 20 to 25 percent of the alumni give money to SMU.

To attract top students, SMU also needs top programs – that’s the only way private universities can survive in competition with the low tuition of public institutions. Since 1962, when SMU undertook a review of all of its programs and produced an impressive self-study known as The Master Plan, it has officially been on record as believing that liberal education is central to its purpose as an institution of higher education. In order to provide a core curriculum that would at least expose all of its students to some work in science, social sciences, art, literature, and history, The Master Plan set up a separate school known as University College.

University College attracted a lot of attention as an innovative approach to undergraduate education. Its courses were to be interdisciplinary, with a faculty drawn from all areas of the university – a visionary scheme in which eminent scholars from the graduate schools of law and theology, as well as from the schools that normally teach undergraduates, would participate. But the vision soon began to give way to reality. Students complained about the excessive number of required courses. The eminent scholars soon found the teaching of undergraduates more burden than challenge. And the courses themselves soon became less interdisciplinary, more like traditional departmentalized survey courses. University College’s “Discourse and Literature” soon came to look more and more like freshman English by another name. The “Nature of Man” course – designed as a challenging introduc tion to the questions dealt with by the social sciences – often degenerated into bull sessions about current events and personal problems or half-baked encounter groups. “Humanities: Insti tutions, Arts, and Ideas” gradually came to look more like good old West ern Civ than anything else. Everyone has a reason for University College’s failure: inept administration, indiffer ent students, a faculty that would rather teach its specialties than experi ment with unfamiliar material. Many at SMU now believe that University College did more to damage liberal education than to provide it.

Zumberge says he makes “no apologies for SMU’s emphasis on professional education. Our setting in a growing metropolis like Dallas, with its diversified industrial base, makes it necessary.” And even in the School of Humanities and Sciences administrators privately admit that they don’t think SMU could continue to attract students if it shifted its emphasis away from professional education. “Students entering college today are threatened by the prospect of being unemployable dilettantes if they major in fields that don’t fit them in a professional pigeonhole,” one faculty member says.

Interestingly enough, however, the dean of the business school thinks the direction SMU has taken academically in the past few years has been the wrong one: “We are too heavily committed to undergraduate professional education,” Coleman says. Ideally, he would like to see the relationship between the liberal arts and the business school become a two-way street, not only with business majors taking strong programs in the humanities and sciences, but with more liberal arts students minoring in business. The emphasis of his own school will be on strengthening its graduate program – and Coleman wants students enter ing that program to have undergradu ate education in fields other than busi ness. Only a third of the students admitted to SMU’s M.B.A. program this fall will have undergraduate busi ness degrees.

For the moment, however, the priority at SMU is money, not curriculum development. That in itself is a significant change. “For a long time, SMU has been committed to innovation for innovation’s sake, with the idea that maybe they’d somehow hit on the magic formula that would transform the school into a first-rate university. But nobody at the top seemed to realize that new ideas need new money to make them work,” one faculty member says.

The Problems

James Zumberge is in charge at SMU. But what will it take for him to stay in charge?

He will have to raise the endowment money. Tackling a goal that large means he can’t afford to fall. He must convince donors that centralized fund-raising is better for the university than contributing money ear-marked for specific projects. He already has the backing of Ed Cox, the powerful chairman of the Board of Trustees and former chairman of the Board of Governors, who was a central figure in the “retirement” of Hardin. Cox now says, “We want the central administration to determine what the spending priorities are for the university.” Cox says that Zumberge already has demonstrated that he knows how to be fiscally responsible, and that SMU will have a balanced budget for the year from June 1, 1976, to May 31, 1977. Zumberge has recommended major expense controls such as restricting travel and tightening up on unauthorized purchases. Cox feels these moves will help convince potential donors that SMU is not only worth the money, but that it now knows how to use it.

Zumberge will have to deal decisively with the problem of football. “We’re on the verge of turning the corner,” he says. “We have a new coach, Ron Meyer, who is a man of proven ability and integrity, and a good recruiter. As long as SMU remains in the Southwest Conference, it ought to try to be competitive, so I think we ought to give the athletic program three to five years to stand on its own feet. It has to generate its own income. I don’t want to see athletics drawing funds away from other areas of the university.”

And Zumberge will have to juggle constituencies while walking a financial tightrope. He will have to convince faculty that one of their own is in charge and is responsive to their needs. He will have to placate a student body upset by constantly-rising tuition. He will have to make sure that administrators are functioning as a team and not just developing little bureaucratic fiefdoms. And he will have to keep governors, trustees and donors convinced that SMU is using its money wisely and well.

James Zumberge looks like a university president. All he has to do is be one.That may be all that SMU needs.

Will UTD Be the Death of SMU?

The University of Texas at Dallas makes SMU nervous. There it is, gleaming on the windy plains of far North Richardson, planning to be a prestigious research institution with upper-level undergraduate work. At cocktail parties this year, after UTD opened its doors to junior and senior undergraduates, with some unusual interdisciplinary programs, people were saying things like “It’s the most exciting school in Texas” and “Boy, have they got SMU scared.”

SMU has reason to be embarrassed if not scared. UTD began life as the Southwest Center for Advanced Studies, a creation of the top echelon at Texas Instruments – Erik Jonsson, Cecil Green, and the late Eugene McDermott. They founded it in the early Sixties to provide graduate education in support of the local electronics industry – Tl, Collins, Vought, and General Dynamics – which was losing talent to competitors in the East and the West, when locals went off to either coast to get advanced degrees. The center’s first home, in fact, was SMU, but it got away, and no one, is quite sure, or willing to say, why. Some say that Erik Jonsson has never taken SMU seriously. “He thinks it’s a branch of the Methodist Church,” says one SMU professor, who worked with Jonsson on Goals for Dallas. “The first time I met him, he asked me, ’Are you a preacher?’ I said no. ’Well, you’re the first person I’ve met from out there who isn’t.’ ” Others, however, speculate that Jonsson, Green, and McDermott really wanted a place of their own to start from scratch. Whatever the reason, the Tl leaders have endowed UTD heavily, starting with the $15 million that founded the center. And while they’ve given money to universities from coast to coast, they’ve given hardly any to SMU.

But if SMU is really worried about UTD, nobody in charge is admitting it. “So far,” says James Zumberge, “we’ve led a peaceful coexistence, and we don’t intend to compete with them. They’re not so demographically diversified as we are.” SMU is after an affluent student body drawn from the entire country. UTD by nature will be for local students who can’t afford SMU, though it will inevitably siphon off many of the Dallas County Community College students who might otherwise have scrimped and saved to continue their studies at SMU. James Early, Dean of Faculties of the School of Humanities and Sciences at SMU, puts it simply, “If we’re any good, their being good shouldn’t bother us.” Early cites the coexistence of public and private universities in Boston, Chicago, San Francisco, and so on as a model working relationship for SMU and UTD

The one reason SMU might have for losing sleep at night would be over the possibility that the Texas College Coordinating Board might allow UTD to establish a law school. In January, 1974, SMU asked the Southwestern Legal Foundation, a non-profit organization offering short courses in legal matters relating to business, industry, and government, to move out of the office space it had been occupying in the law school quad. The Foundation had sponsored frequent appearances by distinguished speakers, and had attracted visitors to the campus that SMU might otherwise not have had. Officially, the Foundation was asked to leave because SMU needed space for its own programs, but there were rumors that the law school administration felt the Foundation was draining money away from the school, attracting donors who might otherwise have given their money to SMU. The Foundation left – and was welcomed into the opens arms of the University of Texas at Dallas, whose president, Bryce Jordan, had already made noises about the “elitist” character of SMU’s law school. “There’s no place for the fully employed person-theC.P.A., the executive who wants some legal training – to go,” Jordan says. The move of the Southwestern Legal Foundation immediately fired speculation that SMU was slipping, and that UTD would build a law school around the nucleus of the Foundation. “We’re not planning to make a push now for a law school,” Jordan says. “But if the citizens of Dallas make a call for a public school in the area, and the legislature and the Coordinating Board echo that call, then we’ll certainly answer it.”

So far, nothing is certain about the relationship of UTD and SMU except that Dallas now has two universities aiming at the big-time. No one seems to know if there’s room at the top for two.

How to Spot an SMU Student

OK. Let’s get it out in the open. Yes, SMU students have taken a bad rap. Yes, SMU students have long been cruelly stereotyped. No, it is not entirely true that if you’ve seen one SMU student you’ve seen them all. No, you cannot automatically identify an SMU student ten times out of ten. (it’s more like nine.)

No fair? All right then, if you don’t like subjectivity, we’ll examine those nuggets of objective truth – statistics. Consider these: Last fall, the American Council of Education office of research surveyed the freshman class at SMU (for the record there were 682 respondents). Facet one of the SMU-student-stereotype: SMU students are rich. Are they really? The survey asked the students to estimate their parents’ income. A staggering 37 percent said their parents’ annual income was $50,000 or more. (The national university norm for this category is less than 8 percent.) Nearly two out of every three SMU freshmen said their parents made over $30,000. Less than 6 percent said that their parents earned less than $10,000. Conclusion: Yes, SMU students are mostly rich. And apparently they mostly want to stay that way. One out of every three of these students-in-cluding almost half the males – said that their major field of study would be business.

Stereotype two: SMU students join fraternities and sororities and thrive in them. True? The survey asked the students if they intended to join a fraternity or sorority. More than 50 percent said yes. The national norm is 19 percent. Conclusion: Greek is good on the Hilltop. Or, as one SMU senior says, “Let me put it this way – someone who makes A’s at SMU isn’t as looked up to as someone who makes a great daiquiri.”

Stereotype three: SMU students are politically ana socially conservative. Wrong. They’re “middle-of-the-road.” That’s how 48 percent classified themselves – 29 percent said they were “conservative;” 22 percent “liberal.” There was almost nothing on the “far left” or “far right” fringes. On specific issues the students consistent in their mildly conservative leanings, as compared to the national norms. Take sex and drugs for example: “Do you think sex is OK if the people like each other?” – 44 percent said yes; the norm is 51 percent. “Should marijuana be legalized 44 percent said yes; the norm percent. On only one issue did the SMU students stray drastically from the norm. “Should the wealthy pay more taxes?” – only 46 percent said yes; the norm is 75 percent. Conclusion: They walk the middle, but, when in doubt, lean right.

All of which is not to say that every SMU student will look like one of the lovely couple pictured here. But if you spot someone who loo , you can bet your class ring it’s a SMUer. Ivy on the Hilltop:

The Greening of the SMU Faculty

“It doesn’t take long for even the dullest student to find out that John Lewis is brilliant,” says Steve Daniels, one of Lewis’ colleagues in the English department at SMU. That opinion is echoed in SMU’s Shopper’s Guide, an irreverent little tabloid that purports to rate the faculty for students looking for good teachers. “John Lewis was the best instructor I have ever had,” one student commented. “He was the most open, fairest, least arbitrary and most intelligent instructor I have ever known.” And one student echoed Daniels’ observation verbatim: “John Lewis is brilliant.” But he added, “However, he tends to presuppose students having more knowledge than is -easonable.”

When we asked students, faculty, and administrators at SMU to name some of he best of the newer faculty, there were ots of nominees: Alessandra Comini and Mary Vernon in fine arts; Daniels, Mi-;hael Ryan, Willard Spiegelman and 3onnie Wheeler in English; Hal Williams. Jeremy Adams, and Judy Mohraz in history; Brad Carter in political science; Bil Beauchamp in French; Barbara Ander son in anthropology, and so on. Bu John Lewis was on everyone’s list.

Lewis came to SMU in 1970. He had been a Junior Fellow at Harvard, one of a prestigious institution’s most prestigious honors – a three-year stipend with no obligations other than weekly meetings and a general understanding that one is to be engaged in research and writing of some sort. His work has been in American literature, specifically in Utopian fiction of the later nineteenth century. A member of the committee that recently reviewed Lewis for tenure at SMU – and granted it – says it is quite simply the most exciting work on American literature he has read in years.

But to say that Lewis’ field is any one thing is misleading. This year at SMU, for example, he’ll be teaching three entirely new courses – historical linguistics (a course offered for credit in both the English and anthropology departments), a seminar in Henry James, and a course in advanced expository writing. His office and apartment are crammed with books – on every topic, in a dozen languages. He will astonish and delight foreign students by speaking to them in Arabic. A conversation with Lewis will ricochet from literature to political theory to philosophy to linguistics to mathematics to art to movies to science. . . .and so on. More than one person has carried on a conversation with Lewis as he was beating time to music on his stereo, watching TV with an earplug, and reading a book like Phenomenology and Science in Contemporary Western Thought.

But for all of this, Lewis remains modest and one of the most accessible of SMU’s faculty. He was voted one of SMU’s outstanding professors last year, but characteristically “forgot” to show up to have his photograph taken for the yearbook. He is most positive about SMU, and highly encouraged by what he sees as signs that the new president of SMU is seriously concerned with the quality of academic life at the university. “I think SMU is a better university than it has realized. It has an excellent faculty, and some very good students. The problem with the students is that the good ones feel isolated, and no one has made a serious effort to get them together. Learning at SMU has been treated as something that goes on in the classroom, that takes place in 50-minute segments, hermetically sealed off from the real world.’’ Lewis would like to see SMU actively promoting the intermingling of faculty and students outside the classroom. “They’ve tried to do it informally, by suggesting that we invite students to our homes. But it has to be more structured than that – and it probably takes money. If it means offering the faculty free lunches if they’ll eat in the dining halls with the students, it’s worth it.”

Like many of his colleagues from the Ivy League, Lewis came to SMU largely out of curiosity – to avoid getting inbred. “There are people so reluctant to leave Harvard that they’ll take any kind of job – working in bookstores, driving cabs – that keeps them in the Cambridge womb.” Lewis chose a job at SMU over a school with a better reputation, Oberlin, because he saw Oberlin as just another little inbred academic world. So far he hasn’t regretted the choice, though he feels some sadness that SMU is off the beaten path, so that visiting scholars and lecturers rarely drop in on the campus. And he sees a danger in SMU’s becoming overstaffed with people from prestigious universities. “Already there’s some factionalism developing – the Harvard Mafia vs. the Yale Maffia.”

Then the conversation shifts, as it does when you’re talking to John Lewis, to The Godfather, to the geography of Sicily, to the philosopher Empedocles, to problems of translating Greek, to. . . .Why is Ron Meyer Smiling?

In 1936, the SMU Mustangs went to the Rose Bowl and put Southern Methodist University on the map. From 1945 to 1949, Doak Walker (and sidekick Kyle Rote) romped in Own by Stadium, into the Cotton Bowl, and into the national headline; – and SMU had a big time name.

It has been downhill ever since. Except for a brief sparkle of excitement from Dandy Don Meredith in the late Fifties, the Mustang glory has gradually tarnished. Interest waned and attendance fizzled as Dallas gave the Mustangs the cold shoulder and embraced new heroes, the Cowboys. Things finally hit rock bottom during the short, ill-fated regime of head coach Dave Smith when the NCAA slapped SMU for illegal procedures. Out went Smith and SMU football lay moaning on its death bed.

But to hear the talk on the Hilltop now, you’d think those troubles had occurred in the long-forgotten past. “We’ve got all our problems behind us now,” says Athletic Director Dick Davis, head cheerleader of the new spirit of optimism.

The key to the new hope is Ron Meyer. An obscure college coach who labored, albeit successfully, in the football boo-nies of the University of Nevada at Las Vegas, Meyer was one name among many when SMU went looking for a new coach last winter. On Super Bowl Sunday, Gil Brandt, personnel director of the Cowboys, contacted the Faculty Athletic Selection Committee with advice to get in touch with Meyer who had briefly served as assistant coach with the Cowboys a few years earlier. In the intensive tests given to all prospective Cowboy coaches, he had reportedly scored higher than anybody – even Tom Landry. Shortly after Brandt’s phone call, Landry himself called – on Super Bowl Sunday mind you – with the same recommendation. SMU got in touch with Meyer. Meyer was ready for them.

“Ron Meyer got the job because he went after it,” says selection committee member Mike Harvey. “All the other prospects saw SMU as a problem. Ron saw it as an opportunity. The others played cat-and-mouse games with us. Ron attacked us.”

Ron Meyer is a young, effervescent, candid man who exudes confidence. He’ll need every bit of it. “That poor bastard,” says one football insider. “He’s got nothing over there.” Dave Smith left behind only the bare traces of a football team and Meyer was hired only in time for some last gasp recruiting. During spring training, the Cowboy coaching staff stopped by to evaluate the 76 Mustangs.”Ron,”they said in verdict,”you’ve got 1V2 football players out there.” The Mustangs are picked by most experts to finish dead last in the Southwest Conference this year. And, to top it off, in the second game of the season SMU plays Bear Bryant’s awesome Crimson Tide in Alabama. Meyer’s response? “Well, the Bear’s gonna have to worry about SMU, too.”

But Meyer is no blind optimist. “Hell, we might not win two games this season. But I can’t preach that to my players. We’ll make the most of it. Our primary concern is not to let this thing bottom out. We don’t want a TCU here. And we aren’t going to bottom out. I won’t really see my own team on the field for five years, but by then we’ll be competitive with any team in the country.”

SMU has, at last, a coach who abides by, in fact believes in, the concept of the student-athlete – students who play football rather than jocks who stumble through the classroom. “It’s the intelligent athlete who wins for you in the clutch,” says Meyer. “I’d be looking for intelligent athletes no matter where I was coaching.” Which should serve to calm some of the students and faculty who openly resented the special treatment approach used by Smith. Meyer contends that a strong academic environment can be used as a selling point in recruiting players and that the approach can work and will work at SMU. “We’ve got a bird’s nest on the ground here,” he says. “If I didn’t believe that, I wouldn’t be here.”

President Zumberge appears to be solidly behind a resurgent effort in big-time football. “He explains his view of the athletic program as the univerity’s ’eighth school’,” says Mike Harvey. “There’s the business school, the law school, etc., and the athletics school. It’s as important to him as any other.” “The man wants excellence in every area of the university,” says Dick Davis. “He wants to be competitive on all fronts. And that certainly includes football.” Not surprising considering that his heritage includes the Cornhuskers of Nebraska and the Wolverines of Michigan.

The football team itself is not the only problem. There’s also the matter of dollars. The football program has lost a bundle over the past several years. “I don’t want to talk numbers,” says Davis, “but obviously we haven’t done well.” (Some estimate that losses have exceeded $200,000 per season in recent years.) “We’ve got to prove to the city of Dallas that we’re going to do things right. We’re only as good as Dallas. And Dallas is essential to the Southwest Conference. We’ve got to turn the attitude of the fans around here

Average home attendance last season was barely 25,000. There are three major problems. One is the Cowboys. They’re good, they’ll continue to be good, and they’ll continue to overshadow SMU in entertainment value. Some see it as an insurmountable problem, citing that most successful college football programs – Ohio State, Texas, Michigan, Notre Dame, Alabama, etc. – exist in smaller college towns without pro teams. Others say there’s room in Dallas for both. It shouldn’t hurt the Mustangs’ entertainment value that Meyer is dropping the monotonous Wishbone offense for the more versatile “I”-formation. Says Meyer, “I’d rather go to the dentist than watch the Wishbone.”

Problem two, especially in recent years, has been scheduling. SMU has taken on such powerhouses as Wake Forest, West Virginia and Santa Clara. Nobody is going to put out seven bucks to watch the Virginia Tech Gobblers. This situation is already being corrected. Scheduling through 1990 already includes such draws as Ohio State, Penn State, Oklahoma, and Tennesse

The third and perhaps most pressing problem is the Cotton Bowl and its location distant from the campus and from most potential patrons. “We would love to get football back on campus,” says Davis. “But it’s just economically unfeasible right now to expand Ownby Stadium to the necessary 45-50,000.” He admits that the Dallas Tornado soccer team’s attendance success in Ownby has been watched with a careful eye, which might encourage a conjunctive effort to expand the stadium. Mike Harvey goes so far as to predict that the Mustangs will be back in Ownby within five years. But Ed Cox, chairman of the board of trustees, says no. “In the first place,” he explains, “it would take $7 or $8 million to get Ownby in shape and even if we had that kind of money it ought to be spent on academics. Secondly, if SMU developed a winning team, we’d have to go back to the Cotton Bowl to handle the crowds.” That issue remains unsettled and will likely become more heated

But it’s the positive aspects that are being promoted now. Everyone involved cites the fine young coaching personnel in all sports – “the best across-the-board athletic staff in the country,” crows one admirer. And many eyes are on the basketball program. “It’s a sleeping giant,” says Harvey. “Sonny Allen [head coach] will win and the facility is paid for.” Fans have already responded – basketball revenues last year alone jumped some $70,000. But football is the key and, in spite of all the other talk, it comes down to that familiar bottom line: winning. “Winning solves a helluva lot of problems,” says Ron Meyer. “Maybe all of them.”

How Does SMU Measure Up?

A comparison of Southern Methodist University with nine other selected private universities, regional and national, suggests that SMU still has some way to go before it catches up with the nations best.

Get our weekly recap

Brings new meaning to the phrase Sunday Funday. No spam, ever.

Related Articles

Arts & Entertainment

DIFF Documentary City of Hate Reframes JFK’s Assassination Alongside Modern Dallas

Documentarian Quin Mathews revisited the topic in the wake of a number of tragedies that shared North Texas as their center.

By Austin Zook

Business

How Plug and Play in Frisco and McKinney Is Connecting DFW to a Global Innovation Circuit

The global innovation platform headquartered in Silicon Valley has launched accelerator programs in North Texas focused on sports tech, fintech and AI.

Arts & Entertainment

‘The Trouble is You Think You Have Time’: Paul Levatino on Bastards of Soul

A Q&A with the music-industry veteran and first-time feature director about his new documentary and the loss of a friend.

By Zac Crain