Maybe in the long run Jimmy Hoffa was right, that “nobody remembers nobody” and fame passes quickly, but here in Dallas the name of a long-dead play director still casts its spell. Margo Jones “happened” in Dallas for only eight years, but she passed through like a fireball, glowing and sputtering, trailing light.

I first came up against Margo in Brennan’s last year. She was not there, of course, since she died from cleaning fluid fumes nearly 20 years before. But the woman New York drama critic Brooks Atkinson called “The Texas Tornado” burned with love of theater, and her fans remember and keep the flame. Two of them, Mary John Barnett and Sarah McGrath, showed up at a fancy luncheon for Farenthold workers and fell back in time when I asked, as a gambit, if they knew Margo Jones.

Both rose to the question and leaned across to me with stories: how Margo made magic in a theater with a tiny stage (only 20 by 24 feet wide), how she came without family connections or a big bankroll and put together the first professional theater-in-the-round in the USA, how she helped launch Tennessee Williams and pioneered decentralizing theater away from Broadway, and how she did it all with will and verve – and John Rosenfield.

If Margo Jones is only a name on an SMU building to waves of newcomers, she is still warm and real to her army of friends. Mary John Bar-nett can still see her late doctor-husband, no theater buff, hurrying to Margo’s for dress rehearsal, then going back 24 hours later to see Opening Night. Sarah McGrath calls Margo’s theater “the best seen in Dallas.” The word-pictures flowed, and Margo appeared: lying on the rug talking on the telephone for hours and reading new scripts, calling everybody “Angel” or “Honeychile,” greeting Dallas by name in the lobby before her showtime….

“Bless you for comin’, honey! Bless you for comin’!” The vivid director exploded with charm, hailing all comers like East Texas kin, reaching out with both hands to draw them in. “No, baby,” she lifted her round freckled face for a peck on the cheek, “I never wanted to act. All I wanted to do was help other people act.” And she did.

The Stardust is gone from her famous playhouse, a small stucco and glass brick building inside Fair Park at First and Grand. No sign remains of her lively art: no paint, no carpeting, no risers, no lights. Wooden picnic tables for museum class lunches stand in place of the 198 seats donated by the father of film star Jennifer Jones. From 1947 to 1955 Margo Jones was the Theater in Dallas. For four years after she died, her experiment rattled and gasped and then finally was gone, too.

The stagestruck dynamo from Livingston, Texas, was downhome folks. “The theater,” she said, “is all of us’s.” At 11, Margo knew what she wanted to be, and up went a sheet for a stage with a curtain out in the barn. Three more years would pass before she would even get a look at live drama, Cyrano de Bergerac with Walter Hampden, playing Fort Worth.

Margo could focus laser-like charm on spellbound listeners. Not the greatest of directors, she nevertheless owned the ability to generate sparks, to call forth special effort and light wildfires of great excitement. Another “cottonchopper,” Tennessee Williams, called her “the most enthusiastic person I have ever met… and the most inexorable.” Playwrights Jerome Lawrence and Robert E. Lee, who wrote Inherit the Wind, said her personality was a “flashflood.” When she entered the room, you knew she was there.

At 14 Margaret Virginia Jones went to college, the only student at the College of Industrial Arts in Denton (now Texas Women’s University) interested in directing plays. There she picked up her nickname and managed to meet two rival newspapermen who would shape her future: John William Rodgers, drama critic and writer with the Dallas Times Herald who later authored The Lusty Texans of Dallas, and John Rosenfield, powerful Amusements Editor for the Dallas Morning News, who autocratically presided over the Southwest’s breakfast table. Rodgers sent her a copy of Shaw’s advice to directors after meeting Margo at a journalism forum, and Rosenfield sent her passes and took her to shows.

Since her college offered no M. A. in drama, Margo took a master’s in psychology on the plays of Ibsen. Just hours after the degree ceremony she landed in Dallas to look for work at a newly formed theater school. Louis Veda Quince, head of the now defunct Southwestern School of the Theater on St. Paul, wanted to know if she could type. A couple of summers spent typing abstracts in her father’s law office got her the job. She stayed for a year, little more than a glorified office girl, to watch the director of the school at work.

After summer classes at the Pasadena Playhouse and a directing stint in Ojai, California, Margo went globetrotting as a rich woman’s companion. Each night on shore she went to the theater. She saw stagecraft practiced in China, Japan, India, England and France. Finally in 1935 she laid eyes on Broadway. It was the night Joe Louis knocked out Max Baer.

On assignment later for the Houston Chronicle, she visited Russia to cover the Moscow Art Theater Festival. There she buttonholed New York Times critic Brooks Atkinson in a hotel lobby. “I’m Margo Jones,” she told him with usual fervor, “and you’re going to hear about me.” “I certainly hope so, young lady,” the taken-aback Atkinson politely replied. Years later he would come to Dallas, watch her work and write: “something of consequence is rising here, in addition to the thermometer.”

Back in Texas Margo joined the Houston Recreation Department, ended up founding the Houston Community Players which grew from nine actors in 1936 to involving over 600 people in the early forties. While in Houston she staged a play about the Reichstag fire trial, Judgment Day, in a courtroom and put on the-ater-in-the-round at a local hotel. She discovered the drawbacks of an amateur group. “I was just killin’ my people. They weren’t professional actors, and they all had regular jobs during the day . . . but I drove ’em so hard from sundown to midnight that they were snappin’ at each other and di-vorcin’ each other and fallin’ fiat on their faces from exhaustion.” She knew then she needed a permanent professional troupe.

During the Second World War Margo went on the University of Texas drama faculty, continued to work with new scripts and arena theater. She took leaves of absence to direct the work of a young playwright called Tennessee Williams. At the Cleveland Playhouse and later Pasadena she staged You Touched Me, a play he had authored with Donald Windham. Margo substantially aided Williams. She directed his The Purification in 1944 and battled like a stage mama to gain acceptance for The Glass Menagerie. “The minute we met in 1939 we talked and talked for three days and three nights,” she once said. “And I bought the beer.”

By the end of 1943 (Margo put it precisely at December 7), her plan for a professional repertory theater had jelled. She appealed to John Rosen-field to recommend her to a friend of his who headed the Humanities Division of the Rockefeller Foundation. She wanted a fellowship to survey theatrical efforts around the U.S. with an eye to designing a civic theater. Rosenfield agreed if she would do it for Dallas.

A former press agent, Rosenfield boosted Dallas and schemed to raise the level of culture. He wanted to make this city a place he could live in. His brilliant wife, Claire, shared in the dream. When Margo and Rosenfield had first met, the Dallas Little Theatre, which took three Belasco Cups in a row, was flourishing here. But by the time of Margo’s fellowship application, the city had no working theater. Margo knew the territory, so it all fit together, and the fellowship went through. Three months into the study Margo was invited to co-direct Tennessee Williams’ first Broadway show, a play she loved, The Glass Menagerie. She left for New York.

The Dallas Little Theatre had flourished and died, leaving behind a salvage committee headed by Ruth McDermott, then married to the oil geologist who helped start TI, and Lon Tinkle. When the City of Dallas began making noises about a children’s theater, John Rosenfield phoned Mayor Woodall Rodgers and put in a plug for grown-ups. He set about expanding municipal vision, came away from a luncheon with city officials carrying a mandate to form a citizens’ group and lay plans for a theater. At Rosenfield’s behest, the salvage committee summoned Margo, then in New York with the Williams play: “If you want to grab the iron while it’s hot,” Rosenfield warned, “get on down here, Glass Menagerie or no Glass Menagerie!” Margo came.

The Dallas Theatre, Incorporated got off with a bang. A billion dollars on the hoof crowded into the Eugene McDermott drawing room for a meeting convened by Ruth, too ill to attend. McDermott, himself, was out of town. John William Rodgers introduced Margo, seated on the floor under the curve of the grand piano. She had just finished her pitch for a new Dallas theater when the big double doors to the drawing room opened, and Ruth McDermott, her leg in a cast, was pushed through in a wheelchair flanked by two nurses. With a snatch of blank verse she presented a check for ten thousand dollars to Margo who leaped up and kissed her on the cheek.

Assured by Rosenfield that it was a good thing for the city, McDermott staked Margo to her theater. It marked the beginning of a touching partnership, the bouncy self-starter and the thoughtful scientist. McDermott agreed to preside over the theater steering committee until leadership arose, but he stayed at the helm until Margo died.

Nearly three years elapsed before Margo’s theater came into being. Postwar housing pressure prevented construction. She applied for a permit to build in North Dallas, but it was refused. Old movie houses and the Museum of Natural Resources were all negotiated for without success. The Old Globe Theatre, a temporary building erected in Fair Park for the use of Shakespearean players during the Texas Centennial, proved an especial fiasco. In the midst of a fund-raising campaign to refurbish it for Margo, the wooden structure was declared a firetrap. Complications and politics snagged all deals, and at one point even a tent was considered.

Twice during the search Margo went to New York, once to stage On Whitman Avenue (a flop) and then to direct Maxwell Anderson’s Joan of Lorraine. Unaware of Margo’s grinding persistence, Dallas wondered aloud if she ever would open. A close friend wrote her about the cynicism: “The situation isn’t rosy. You must face facts. Everyone is waiting to see the color of your cards.” Margo even entertained the idea of a hotel room similar to her set-up in Houston. Finally the Gulf Oil Company agreed to lease its Exhibits Building for free (except for utilities) in exchange for a mention in Margo’s PR.

Against best advice Margo opened in summer amid what Brooks Atkinson called “the vehement heat.” Slow at first, business picked up until the total summer season attendance was 12,983 for 80 shows. When Theatre ’47 opened that November (she always had to wait until after the Fair) only $199 was on hand (not counting advance ticket sales). By the end of the season $12,000 was in the bank, an average profit of $500 a week. Zelma Naylor, who runs the box office at the Dallas Theater Center, learned her trade with Margo Jones. She recalls the scramble for seats, even selling 25 tickets just to sit on the steps. Margo’s theater was the rage, the “in” thing to do, and tickets were only $2.50 each.

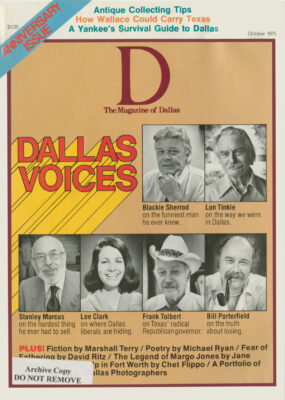

The team of Rosenfield and Jones brought an institution to Dallas that gained world-wide fame. SMU’s Lon Tinkle, lecturing for the State Department on “LBJ Country,” found listeners in Tunis, Morocco and the Ivory Coast more interested in Margo than the Pedernales.

Would professional actors want to work in the provinces, 1500 miles away from The Great White Way? The first season 200 written applications came in from actors eager for repertory work. Margo’s company received Equity minimum pay, $75 a week in cash. The upper limit for staff and crew, including Margo, was $100. Charles Proctor, who went into the troupe out of SMU, recalls having one day off every three weeks. Rehearsals went on all day with a show at night. “We worked long and hard,” actress Joan Croydon remembers, “but we didn’t mind because we loved Margo and the Theatre.” “A day without rehearsal,” Margo said, “is a day wasted.”

“Did I start theater in the round?” Margo repeated the reporter’s question. “No, honey, the Greeks did.” Arena theater meant new techniques, intense concentration and a fluid choreography to give all sides of the house a piece of the action. In a cockpit theater special problems arose. Swordplay and gunshots scared the audience, none of whom were more than five rows away. Musical instruments had to be mastered and real card games played. There was a loss of aesthetic distance for love scenes and quarrels. “Any false reading or phony performance was perceived at once,” Joan Croydon recalls. “You just had to be real, no overacting.” Margo showed how to “make the rounds,” by pulling down a girdle for one side of the house while grimacing for the other. Or by flicking ashes in trays strategically scattered around the stage. Proctor rehearsed with one young method actor who asked Margo the motivation for his turn. “Why, honey,” she sweetly explained, “there’s no motivation. The audience across the room just gets a look at your face.”

Such close quarters bonded actors and audience, both accustomed to the dark anonymity of the proscenium stage. According to Lon Tinkle, “We practically held hands and sat there, radiating courage to the actors.” When one performer had trouble getting his cigarette lighter to work, a hand reached out across the second row with a light, a member of the audience to the rescue. Another play called for a young ingenue to walk offstage, apparently to her doom at the hands of a psychotic killer. “Don’t go in there!” screamed a voice from the audience. In Thong O’Scarlet, when an actor stamped his foot and shouted “Can’t we do something about these rats?” women in the first row pulled their feet up on the seats.

The first cat tried in How Now, Hecate drew an early notice, but the second one looked like a real stage trouper. She had been through rehearsals but never experienced applause. When the clapping started, the cat clawed the actress holding her, who in turn lost her way in the dark and fell into the lap of a man in the first row. Perhaps the height of intimate theater came when Mary John Barnett’s daughter, then a little girl, laughed at a Shakespearean gag line in Taming of the Shrew before any one else. Actor Tod Andrews gratefully turned and threw her a kiss.

Repertory playing was something else again. At the end of the regular season the company presented all of the season’s plays in a two week festival. Charles Proctor tells the story about the actor who paused during a performance in repertory week. “What’s the next line?” he wanted to know. “Line, hell!” was the comeback. “What play is it?”

Mabel Duke, the veteran publicist, served as Margo’s friend and press agent. But Margo, in a sense, was her own best flacker. “Figure,” she said, “that I’m 51% creator and 49% promoter.” She fired herself around town and Texas, speaking to clubs and spreading the word. She has been called “the St. Joan of the theater” and “the Aimee Semple McPherson of the arts.” The fabled will and energy made her hard to resist. Everette De Golyer liked to call her “Crisis” Jones.

Arthur L. Kramer, Jr. a student at UT when Margo was there and Theatre board president after her death, tells about Margo’s setting her heart on a station wagon. The theater needed a car, but couldn’t afford it. Despite warnings from friends that she didn’t stand a chance of getting blood (and certainly not any rolling stock) out of this particular turnip, she went to the dealer. Living up to the legend growing around her, Margo walked out with a free station wagon.

“All I want for an actor to do,” Margo said, “is make me believe.” Patient with actors, good-natured and kind, Margo called forth top performances from the company. The theater was her life, her marriage, she called it “her baby.” Actors felt a part of her personal family. Before each opening night, every member of the cast and crew, maybe 40 in all, received a personal handwritten note from Margo Jones. Her refusal to take a salary much higher than theirs endeared her to co-workers.

Among actors who worked here and later gained reputations were Tod Andrews, Mary Finney, Charles Bras-well, John Hudson, Peggy McCoy, Peter Donat, Rex Everhart, James Field, Louise Latham, Ray McDonnell and Clu Gulager. Jack Warden, a great Dallas favorite, plays the cuckolded husband in the movie, Shampoo.

Her special madness was a playwright’s theater, a place where brand new scripts could be produced. She dared to experiment, to showcase young writers like Williams and Inge and Lawrence and Lee. “There are more scripts on mimeographed sheets,” Margo insisted, “than on the stages and screens of America.” She saved a sheaf of new plays from sure oblivion, from what Williams has called “the limbo of libraries.” Inherit the Wind had been turned down by 12 producers when her business manager, Tad Adoue, sent her the play with a note: “I double-dog dare you to produce this!” She did.

Sandwiched in among the virgin material were vintage classics – at least 50 years old was Margo’s guideline. She staged Shakespeare, Ibsen and Moliére, once did Shaw but feared dipping under the 50-year-bot-tom line lest she get “sucked in” to warmed-over Broadway.

Margo staged her share of turkeys along the line. Brooks Atkinson called How Now, Hecate “nothing more substantial than stewed fish’s eyebrows” but admitted it was better than “sitting up with the radio at home.” Local playgoers, caught up in Margo’s experiments with new scripts, watched the first-runs with a curious mix of acceptance and interest. “I can’t come to dinner tomorrow night,” Dallasites were heard saying, “I’m going to Margo’s, and I hear it’s lousy.”

But even when a new script laid an egg, “Something was exciting,” bookman Lon Tinkle said. “The exits, the lighting, the costumes, the camarad -erie.”And of course there was Margo always at the door: “Now, honey, this one didn’t quite come off, but next week . . .” Dallas drama critics took aim and fired, but, pro that she was, Margo never complained.

“There were some beauts, some real nightmares,” hoots Betty Winn Campbell who served as Theatre Board Secretary and freely admits enjoying the clinkers. “We had fun rewriting those plays on the way home.” Despite public high spirits, Margo suffered when a play fell flat. Friends tried to pump her up, but there were less than gala nights. Offsetting the duds were Inherit the Wind, Summer and Smoke, Farther Off from Heaven (her Dallas opener reworked for Broadway where it became The Dark at the Top of the Stairs) and a local box office hit called Southern Exposure. Margo’s track record was better than most.

What he called her “inability to correct or shape a script in rehearsal” seemed to John Rosenfield Margo’s great directorial weakness. Margo cherished the playwright’s work and refused to touch even a line. She made it a point to read at least one new play a day and ran a clearinghouse for new scripts. “I like to be swamped with scripts,” she said, and she meant it.

Friends who stopped by Margo’s bedside during her final days remember her bubbly as usual. At the time the Dallas Dynamo’s kidneys were shot and her urine had turned black. Asked if they could bring her anything, Margo pointed to a big stack of new plays: “Angels,” she said, “I’m going to read all of those before I get out of here.”-A drummer to the end, she planned a newspaper picture showing her choosing plays from her hospital bed.

Margo considered long runs “pernicious” but two of her productions did run over. Southern Exposure, a comedy John Rosenfield called “a carbon copy of The Philadelphia Story in a Natchez setting,” tickled Dallasites more than New Yorkers. Inherit the Wind, revived last January at the Dallas Theater Center in celebration of its twentieth year, proved a smash from the first. So powerful was the revival scene with actors planted in the audience that even John Rosenfield felt like shouting with the spirit. The authors started the Margo Jones Award to honor anyone who can match her daring in discovering new plays and their writers.

Summer and Smoke, poignant in the arena setting here, lost magic when spread on a proscenium stage. It played Broadway 102 times, then went on tour. Revived later with Ger-aldine Page for the 200-seat Circle-in-the-Square in Greenwich Village, the Tennessee Williams work came into its own.

In a way Margo Jones was part Peter Pan, the Eternal Child with a “little-girl giggle” and “sparkling eyework.” She was earthy and salty and partied hard, but she ended loving notes to her family with “Your Little Girl” and wrote over and over that she would try to be worthy of them. Religious folks who failed to understand their daughter’s obsession with the stage, Margo’s parents never journeyed to Dallas to view her success. Brooks Atkinson wired her at her tenth season testimonial luncheon: “I doubt that your theater has lost a minute of its youth. I hope it always has the mind of an adult and the heart of a girl, your heart to be precise.”

Margo gave herself over to anyone starting a civic theater. When a playhouse needed launching or shoring up, Margo was there. She arranged to transport her whole cast to Houston to help Joanna Albus’ ailing theater. Another time she blitzed Oklahoma City for The Mummers. When Mary John, who started the highly successful Milwaukee Repertory Theater, needed initial support, she came to Dallas. At Rosenfield’s suggestion Margo plunged into directing Walls Rise Up for the Round-up Theatre with talent from the black community.

Genuinely supportive of theater extension, she even served on the board to get the Dallas Theater Center going. “Glory to Betsy, I Second the motion!” she said at the meeting to get the project underway. “Theater’s like watermelon,” Margo believed. “You can’t have too much watermelon, and you can’t have too much theater.” She showed up to fundraise for the Center, and friends say, “If you think she was resentful, you didn’t know Margo.”

Ironically, the Theater Center stands on property offered to Margo by Sylvan Baer and then withdrawn. She tramped over the land between Blackburn and Lemmon and chose a site. Ironically, also, Frank Lloyd Wright was her first choice as an architect. She had lived in Wright’s Hollyhock House on the Aline Barns-dall estate while studying at Pasadena.

McDermott sent her to Taliesin West, Wright’s home in Arizona. The Dallas Morning News head was “Margo Jones Off to See the Wizard.” She found the architect unfriendly to arena theater and disagreed with him on backstage space. Wright had plans for an unbuilt theater designed in 1913 and updated in 1949. “He doesn’t know anything about the theater,” Margo wrote to a friend, “but there is a possibility we might work something out.” Eventually she gave up and opted to pull a local architect “up to greatness.” She died before her dream could come true.

Her death came so insidiously and suddenly even close friends were unprepared. In an after-hours art session with friends, she had spattered paint around her apartment in the Stoneleigh Hotel. Carbon tetrachlor-ide finally removed the spots from the sofa and rug where Margo read scripts and made phone calls that evening. She spent the night on the sofa in a closed and air-conditioned room. The next day she felt ill and rested inside, still seeking a new play to put into rehearsal.

On July 15 she went into St. Paul’s Hospital. X-rays showed severe kidney damage. A consultant linked the case to carbon tet fumes compounded by alcohol in the system. Margo was taken to Parkland for its kidney machine, but her heart failed, and she died on July 24, 1955, only 41 years old.

Virgil Miers, Times Herald Amusements Editor, wrote her a tribute, “Goodbye, Sweet Tornado.” “Margo had her share of greatness,” William Inge said, “more than most know.” To Rosenfield Margo’s “greatest frustration in life was that she wanted to be a great lady and never realized that she was.” Arthur L. Kramer, Jr. feels the tragedy was that she was so much better known outside of Dallas. Jerome Lawrence writes in Actor: “That lady had more guts than any human being I’ve ever known.”

Even friends who knew her called her obsessive, a fanatic who never took time out to count up her accomplishments. Always in motion, she sometimes ran like an engine out of control. Others claim her strong attachment to Manning Gurian, onetime business manager of the Theatre who went on to marry Julie Harris, led to heavy drinking. Frustration over artistic failure took its toll. Pictures taken over the years show a pert, snub-nosed face alive with spirit, bloated and puffed beyond her years. At the tenth anniversary luncheon where a grateful Dallas did her honor in 1954, the Dynamo looks older than her 40 years.

Ramsey Burch, a competent director who worked interchangeably with Margo, took over the theater after she died. He tried, and partly succeeded, but the Great Energizer, the Life Force was gone. A move from Fair Park to the Maple Avenue Theater (near the Stoneleigh P) meant a switch to proscenium. The ghost had been made to walk for four years, and the long wake was nearly over. The board paid off all debts, gave the costumes and lights to SMU, and donated letters and files to the Fine Arts Department of the Dallas Public Library. Margo’s collection of nearly 8000 turtles in all shapes and sizes went to friends.

In Don Marquis’ archy and mehit-abel, archy the cockroach watches inhorror as a moth tries to immolatehimself on a light bulb. Archy thinksit over and opts for survival butwishes he cared as much about anything as the moth seemed to careabout frying himself. Paul Baker ofthe Dallas Theater Center feelsMargo worked herself to death, basically unsupported by the city sheburned to please. I doubt that MargoJones would agree. Her candle hadlong been ablaze at both ends (shemade one serious suicide attempt) butfor eight years off and on in Dallasshe and her theater had made a brightlight. After all, the Texas Tornadowas opposed to long runs.

Get our weekly recap

Brings new meaning to the phrase Sunday Funday. No spam, ever.

Related Articles

Arts & Entertainment

DIFF Documentary City of Hate Reframes JFK’s Assassination Alongside Modern Dallas

Documentarian Quin Mathews revisited the topic in the wake of a number of tragedies that shared North Texas as their center.

By Austin Zook

Business

How Plug and Play in Frisco and McKinney Is Connecting DFW to a Global Innovation Circuit

The global innovation platform headquartered in Silicon Valley has launched accelerator programs in North Texas focused on sports tech, fintech and AI.

Arts & Entertainment

‘The Trouble is You Think You Have Time’: Paul Levatino on Bastards of Soul

A Q&A with the music-industry veteran and first-time feature director about his new documentary and the loss of a friend.

By Zac Crain