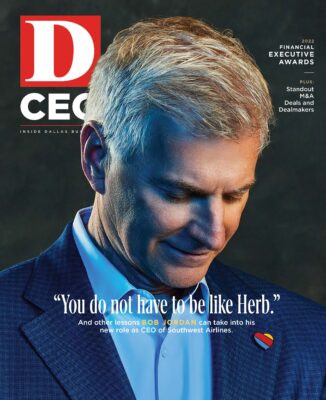

Bob Jordan’s new office is mostly empty. There’s a desk and a few chairs, including the high-backed, black leather model Jordan is sitting on. It’s the first day of February 2022, Jordan’s first day in this office. His first day as CEO of Southwest Airlines.

Jordan swivels in his leather chair and points to the bare walls behind him. “We’ve got some cabinetry coming for the walls back here,” he says. “But like everything in the supply chain now, there’s a long lead time for cabinetry. I think it’s eight months. So, everything is in cardboard boxes for now.”

The CEO of a $22 billion company (pre-pandemic) will be grabbing files and whatnot out of cardboard boxes. For eight months! The CEO of Southwest Airlines probably hasn’t done such a thing since mustachioed Lamar Muse, the first to hold that title, moved into an inexpensive, wood-paneled office above the original Love Field terminal back in 1971 and watched the first-ever Southwest flight rumble down the runway on the morning of June 18—50-plus years ago. Southwest only had three planes then and about 100 employees. Today it has 56,000 workers and plans, soon, to have 1,000 jets in a fleet that already flies more people across the U.S. than any other carrier. But it’s short on cabinets?

“We’ll also have to put some Southwest Airlines stuff up on the walls,” says Jordan, a Jeffersonville, Indiana, native who has spent most of his 61 years in Texas and who speaks with a mashup accent that’s both Texas twang and Midwestern flatness.

Ah, but which stuff should go up there? Maybe a framed copy of the ad Southwest ran in 1973, featuring a picture of Muse offering passengers a free bottle of booze if they’d pay full fare on Southwest instead of flying for $13 less on competitor Braniff. “Nobody’s Going to Shoot Southwest Airlines Out of the Sky for a Lousy $13!” Muse exclaims in the ad, which almost singlehandedly turned Southwest from a money loser into a profitable carrier. Or, hey, what about a picture of some original flight attendants in their red-orange hotpants, slouchy white belts, and lace-up, white go-go boots? Is that too sexist? Well, then, perhaps a snapshot of Herb Kelleher, the legendary, chain-smoking, Wild Turkey-drinking Southwest CEO whose kooky, maverick personality was, for decades, the very personification of the Southwest brand. A shot of Herb dressed up in that Elvis Presley jumpsuit he used to wear on Halloween would be especially wall-worthy.

Then again, Jordan could go abstract with an artsy, chartsy rendering of the 47 consecutive years that Southwest posted an annual profit. That streak began with Muse and continued through the tenures of four other CEOs, including Gary Kelly, now executive chairman of the board. The pandemic snapped that profitability in 2020, but no other passenger airline has enjoyed that much bottom-line success for that long. Now, it’s Jordan’s job to get the streak started anew.

It might help that he isn’t new to Southwest or its successes. He has been with the company since 1988, coming on board as a 27-year-old programmer with a computer science degree and an MBA from Texas A&M University, as well as a mustache that would have made Muse proud. In the ensuing decades, Jordan bounced around the airline, eventually holding—he thinks—15 different job titles, including everything from controller to chief commercial officer.

Now silver-haired and sans stache, the job ahead of Jordan won’t be easy. He’ll have to navigate the severe turbulence the pandemic has created for the entire airline industry and for Southwest in particular. To do so, Jordan could call on some of the lessons in leadership that he’s learned from all 15 (or whatever) of the jobs he’s held. In fact, four of those lessons might be especially helpful. These four.

01.

Titles don’t matter, even if you’ve had a lot of them.

In the past two years, Southwest has not only lost money, it has also seen serious dips in its on-time reliability and experienced erosion in morale, according to some union leaders. That’s partly why Jordan’s theme for his first year as CEO is “back to basics.” Perhaps not coincidentally, that was also the theme of the Southwest Airlines annual report in 1988—the year Jordan first came on board, and the year he learned his first big lesson in leadership.

Jordan came to Southwest knowing little about the company, he says, even though he had been in Texas for a while. He’d moved with his family to Houston in 1974 and had enrolled at Texas A&M four years later, initially hoping to become an electrical engineer. “I got to studying differential equations,” Jordan says, “and I realized that electrical engineering was going to be really hard.” He shifted into studying architecture and ended up sketching houses for individuals and working up architectural renderings of an atom smasher for the university, which was in the market for such a device. “I put myself through college with those drawings,” Jordan says.

In the end, he dropped architecture and got an undergraduate degree in computer science. Along the way, he married an A&M classmate, Kelly Potz-Nielsen, and after graduation, enrolled in the MBA program as he waited for his wife to complete her history degree. After the birth of the couple’s first child, and a brief stint working for Hewlett-Packard in California, Jordan returned to Texas to work on Southwest’s HP systems. He was soon tapped to join a big programming project for the finance department, which was headed by the company’s controller, “a guy named Gary Kelly,” Jordan says. The project involved weeks of intense work, and, at the end, Jordan received a thank you note from Kelly. The note included a gift of points that the company gave to workers, which they could cash in for stuff. Kelly gave Jordan enough points to buy a couple of bicycles. But the note was worth much more than that. It changed Jordan’s life. “I was just a programmer, but here was the corporate controller taking notice of me,” Jordan says. “I knew then that Gary was the kind of person I’d love to work for one day.”

When a job opened in finance in 1990, Jordan applied, got it, and worked under Kelly. It was the last job he ever applied for at Southwest. All his subsequent 13ish positions, including the CEO job, came because Kelly personally tapped Jordan to do something new. “Gary basically just moved me around and allowed me to do different things,” Jordan says. “That’s why I call him a sponsor and not a mentor. A mentor talks to you about things, but a sponsor puts you in positions that develop you, that stretch you.”

Jordan didn’t plan on being a manager, and he certainly never envisioned himself as CEO. But Kelly pushed him—stretched him—into multiple leadership roles, whether Jordan thought he could perform the jobs or not. One example: In 1997, Kelly, who was chief financial officer at the time, asked Jordan to take on the corporate controller role. Jordan recalls telling Kelly, “‘You realize I don’t have an accounting degree, right?’” To which Kelly replied, “You have an MBA.” Jordan responded, “Yeah, but I only took six hours of accounting classes.” Kelly looked at Jordan for a few seconds and said, “Well, you’ll figure it out.”

Somehow, he did figure out all the stuff he needed to know about liquidity ratios and horizontal analysis and the difference between 10-Ks and 10-Qs, and the company posted record net income that year (a record that has since been broken several times). Jordan says he learned that titles don’t matter, but the work does. “I’ve never been a title or career progression person,” he says. “I just love doing new things. I love the work. I love the people. If you love those things, everything else will just kind of take care of itself.”

02.

Know what you don’t know.

The day after Southwest closed its $3.2 billion acquisition of AirTran in 2011, Bob Jordan flew to Orlando and walked into the company’s low-slung headquarters building at palm tree-lined 9955 AirTran Blvd. He was there to meet with top leadership after taking over as the company’s president—at Kelly’s request—for a three-year-long integration period for the two airlines. “I stepped into a staff meeting,” Jordan recalls, “and I didn’t know who anyone was.”

To bridge his knowledge gap, he followed the same script that had worked for him in his previous, unexpected roles. First, figure out what you don’t know. Second, find people who know what you don’t. Third, let them go to work. “I’m not the smartest guy on the planet,” Jordan says. “I don’t know everything. And no one can do everything by themselves. So, job one is to form a team of people you trust that can get the job done.”

Building that trust with Southwest people he’d worked with for decades was easy. But to do so with AirTran leaders he had just met took more time and a lot of talking, which just so happens to be something Jordan loves to do. “Bob has the gift of gab,” says Southwest CFO and Executive Vice President Tammy Romo, who has been working with Jordan ever since she joined the company in the early ’90s. Jordan doesn’t deny that he’s not the kind of guy you want sitting next to you on a plane, but he says that, on the job, what he’s really after is detail. He grabs a yellow notepad that’s on his desk and holds it up for me to see what he means. “I’ve always got one of these with me,” Jordan says. “You’ll always see me taking notes. I just tend to want to know a lot. If you ask people about my leadership style, I think they’d tell you that, ‘He’s analytical and probably annoys you to death with questions.’”

Actually, no one told me that. Not exactly, anyway. What they did say is that there’s a term around Southwest’s offices, “Bob Math,” that staffers use when explaining how Jordan processes information. “Bob grasps numbers really well,” says Mike Van de Ven, the airline’s president and chief operating officer. “And he identifies trends well. I think Bob can solve differential equations in the back of his mind while he’s holding a conversation.” Clearly, Van de Ven is unaware that Jordan dropped his electrical engineering classwork at A&M because differential equations were too hard.

03.

You should own up to your weaknesses.

Twenty-something years ago, maybe when Jordan was the director of revenue accounting at Southwest Airlines, or possibly when he was the corporate controller, but most definitely after he had been the manager of sales accounting, he had an important meeting. It was with Colleen Barrett. She had been an executive assistant for Herb Kelleher at his law firm before joining Southwest, and eventually rose to the rank of president at the airline. She was the keeper of the company’s corporate culture and was Kelleher’s wrangler—doing her best to keep the easily distracted CEO on course. “Herb can’t say hello in just 15 minutes,” Barrett once quipped.

As Barrett met with Jordan, Kelleher wandered into Barrett’s office, looking for a cigarette—one of the 100 Kelleher would have smoked on a typical day. “Hey Bob,” Jordan recalls Kelleher saying to him, “I just got a new car. Want to see it?” Jordan followed Kelleher out the door of Barrett’s office and down two flights of stairs. Along the way to the parking lot, Kelleher stopped to gladhand and backslap male employees and kiss female employees right on the lips. He also made conversation. A lot of conversation. Jordan remembers a lot of those “hellos” Barrett was talking about. “It took us about half an hour just to get outside,” Jordan says. “When we did finally get to the car, Herb realized he’d forgotten his keys. We had to go back upstairs and do the whole thing in reverse.”

When they finally reached the new sports sedan, Kelleher told Jordan he wanted to take him on a drive. “The whole interior was covered in cigarette ashes,” Jordan says. “I sat down, and my pants were immediately covered in ashes, too.” Kelleher zipped away from the airport, steering over to Texas Stadium and then out through Grand Prairie and Arlington. The ride went on and on, until Jordan said, “Herb, don’t you have somewhere to be?” When they finally got back to Love Field, Barrett was impatiently waiting in the executive suite. Three hours had gone by. “Colleen yelled at me up and down,” Jordan says. “She told me, ‘You lost Herb!’”

In his 34 years with Southwest Airlines, as he has taken leadership positions making him responsible for the company’s accounting, its purchasing, and its people, that was probably the most trouble Jordan had ever been in. “Other than being an Aggie,” says Romo, a University of Texas graduate, “Bob is pretty much perfect.”

Actually, he’s not. In fact, Jordan has consistently done two things imperfectly for pretty much his entire time at Southwest, and he’s not at all embarrassed to cop to them. “The same two things have shown up on my appraisals for 34 years,” he says. The first of those things is a tendency to be impatient. “I try to overcome that in every meeting I’m in,” Jordan says. “If you’re too impatient to get details from someone, that can send the impression that the other person and what they have to say is not important. That’s the last message that I want to send.”

The second thing on those performance evaluations is that Jordan sometimes moves too quickly on any given assignment, sometimes snatching responsibility for executing that assignment away from the people who have been tasked with it. “I’ve been told to just let the process develop instead of trying to drive it,” he says.

But hold on. So, Jordan is impatient and sometimes moves projects forward too quickly? Maybe that’s good, especially right now when Southwest is trying to get back to profitability and make amends with employees who have been stretched to the breaking point by the pandemic and by the airline’s shortage of staffing.

“We’ve got probably 35 or 40 aircraft that we can’t fly today because we’re not fully staffed,” Jordan says. And more planes are on the way. Jordan expects to buy enough new 737s in the next few years to bring the Southwest fleet to 1,000 planes. That would allow the airline to operate 5,000 flights a day—or 1,000 more flights per day than it operated in 2019 before the pandemic hit. This, in turn, would allow Southwest to fully service all its destinations, including new routes to Hawaii and to the 13 different cities Southwest added to its network during the pandemic. But without more workers, those planes won’t do Southwest any good.

Jordan says the company wants to add 25,000 new workers by the end of 2023, expanding the current workforce by 43 percent. That would be the biggest three-year employment expansion in the airline’s history. For some, those workers can’t come on board fast enough. Lyn Montgomery, president of TWU Local 556, the union representing Southwest’s flight attendants, tells me she fears the company will face more attrition if it doesn’t improve the working conditions that flight crews have been operating under in recent years. Still, Montgomery is optimistic that Jordan may be able to help make that happen. “He’s very affable,” she says. “And he seems to be people-oriented. But he has a really tough task ahead of him.”

Beyond the people problems making that task tough, Jordan must figure out why Southwest’s typical on-time performance plunged from 80-ish percent in May 2021 to 60-ish percent in June. He also must ensure the airline doesn’t suffer the cascade of cancelations that affected its network over two different weekends last year. During the Columbus Day holiday alone, Southwest canceled some 2,500 flights after people and planes were left out of position, thanks in part to bad weather in Florida.

Capt. Casey Murray, president of the Southwest Airlines Pilots Association, says his members have griped for years that the company hasn’t invested in the right tech tools to prevent those kinds of cancelation waves from overwhelming the system. But he, too, is optimistic that Jordan may finally listen to the pilots’ complaints. “I think Bob does listen and actually hear our concerns,” Murray says.

04.

You do not have to be like Herb.

Back in 1992, when he was about Jordan’s age, Herb Kelleher faced off in an arm-wrestling match with the owner of Stevens Aviation, a small aircraft sales company, over the rights to a slogan both Southwest and Stevens were using—a variation of “Just Plane Smart.” Kelleher, with a cigarette dangling from his mouth and with a middle-age paunch puffing out his T-shirt, lost the highly theatrical battle that was dubbed “Malice in Dallas.” Jordan likely would have easily won the same contest. He regularly bikes, runs, and lifts weights. His biceps bulge from under the polo shirts that are typical at the all-week casual Friday offices of Southwest.

The non-smoking Jordan is anything but Kelleherian in one other way, too. A few years after “Malice in Dallas,” Kelleher told me it was his plan to “die in my chair” at Southwest. At the time, Kelleher lived in a University Park townhouse, even though his wife lived in San Antonio, and he was putting in 16-hour days and sleeping four or maybe six hours a night. (Kelleher did finally accept retirement, leaving the CEO post in 2001 and the chairman’s job at Southwest in 2008, well before his death in 2019 at age 87.)

Jordan, who obviously isn’t thinking about retirement just yet, because he’s got an office to decorate, is not putting in those kinds of hours and has never been the “die in my chair” type. Beyond his fitness routine, he is an amateur woodworker who also likes to play the board game Risk and do indoor rock climbing. He wants his fellow leaders at Southwest to have interests of their own that get them out of their office chairs, too. “What I don’t need to tell our leadership team, our operational folks, is that they need to work harder,” Jordan says. “They’re already working hard. They’re pouring their life into Southwest Airlines. What people do need to be told is that they have permission to let other things be important as well, like their family. They have permission to not feel guilty for doing things that put balance into their lives.”

Then again, Jordan admits he’ll have a little less of that balance as CEO than he did in all those other roles he’s served in at Southwest. “It’s going to get harder, for sure,” he says. “I’ve got a lot of work to do.”