I’m going to spoil a pivotal event of Paul Thomas Anderson’s Magnolia, but if you’ve not yet gotten around to seeing that brilliant, now 15-year-old film, then face up to the fact that you likely never will and don’t hassle me for spilling the following secret.

Magnolia tells a collection of interconnected stories of people in Los Angeles. There’s nothing too far-fetched about its plot lines about ordinary people moving about their fairly ordinary lives when, without explanation, it begins to rain frogs. By which I mean, full-sized frogs fall from the sky. There are apocalyptic, Biblical overtones, but no vengeful god appears to take credit for the act. It’s ridiculous. Makes little sense. Comes out of nowhere and alters lives.

The best explanation for the sequence that I’ve ever heard came from the late actor Philip Seymour Hoffman, who appears in Magnolia as a nurse caring for a man dying of cancer. He said — and I’m sorry that I can’t locate the interview anywhere online, so you’ll just have to trust my fading memory — the rain of frogs began to make sense to him when he thought about cancer.

Why we shouldn’t we accept the possibility of a downpour of amphibians when we’ve become accustomed to a plague like cancer? Cancer is your own body turning against itself for ultimately mysterious reasons. It’s ridiculous. Makes little sense. Often comes out of nowhere and alters lives.

I’m sure that when, in 1976, 30-year-old Judith McPheron began to suffer an onslaught of clumps of tissue growth all over her body — a rare form of cancer known as liposarcoma — she could hardly have been any more shocked if she’d glanced out the window and seen frogs descending from the sky.

In November 1981, then D Magazine staffer Michael Berryhill movingly told the story of McPheron’s final years, of how she confronted the coming of her own death through her poetry. It’s one of the 40 greatest stories the magazine has ever published.

In an editor’s note in the issue, Rowland Stiteler commented on how Berryhill had been changed by the story. He was “distracted” and “noticeably saddened”:

As he sat in his study at his typewriter, he took her through months of chemotherapy, through temporary triumphs and depressing defeats, and, finally, to her deathbed. It is significant that when Berryhill called to say he was finished, his first words were, “I’ve killed her.”

I asked Berryhill, who is now a journalism professor at Texas Southern University in Houston, to reflect upon the piece. He shared these thoughts:

I wish I could say that after D Magazine published “Death of a Poet” I went on to publish article after article that was just as good. But that didn’t happen. Such stories are such a combination of good luck, hard work and inspiration that they are difficult to come by.

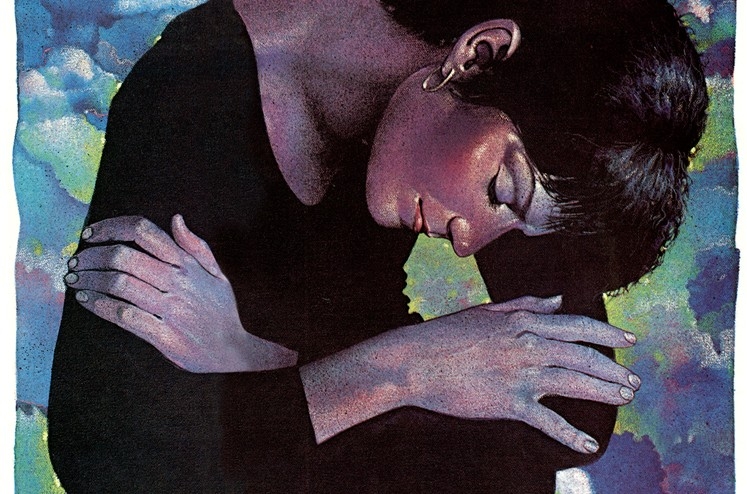

I had some preparation for writing about Judith. I started out as a poet and published poems as an undergraduate at Kenyon College and as a graduate student at the University of Minnesota’s program in American studies. I was working at the Fort Worth Star-Telegram at my first job as a reporter when I met Judith very briefly at a poetry reading at the Dallas Public Library. I was struck by her beauty, the brilliant scarf she wore to cover her bald head, and her hooped ear-rings. I’d heard she was a good poet. She didn’t have the strength to stay for the party. Someone told me she was dying of cancer.

When Rowland Stiteler hired me to write for D that summer, I pitched him the story of Judith. After a little checking, I found she had died. But she had left a trove of journals and poems with her best friend, Frances Bell, the librarian. I trimmed the journals down, and after typing a couple of pages, turned them into present tense. This was an effect that poets often use, and it worked for Judith’s story. It’s as though she never died, as though she is always alive, always present.

The rest of the story was the result of reporting, reporting, reporting: talking to her friends, building the narrative, putting the bits and pieces together about her circle of friends, and trying to make her as real as possible. The worst thing would have been to sentimentalize her.

The story won the Texas Institute of Letters prize for nonfiction. In 1985, Corona Publishing of San Antonio published Judith’s poetry collection, This Leaving We Cannot Live Without.

I sometimes teach this story in a class on literary journalism. I still have the typed notes from the interviews and the photocopies of Judith’s journals. My contribution was the work. Judith provided the magic.