One of the key reasons students say they want to go into medicine is because they want to make a difference for their world. Having a job that pays you well to make a difference is a fair reward for the 11 to 16 years of education, hard work, and continued self-sacrifice physicians endure. As government budgets squeeze ever tighter, the average payments for many of the things physicians do to make that difference has consistently dropped over time.

Inflation steadily grows the main expenses of practices: real estate and employee salaries. To stay in business (and pay their student loans) providers have few choices to provide revenue. When prices are fixed by the government as in Medicare and Medicaid and when insurance companies are allowed to nearly monopolize on rates, the most direct choice is to increase the volume of services doctors provide. The pressure to do more and more is undeniable.

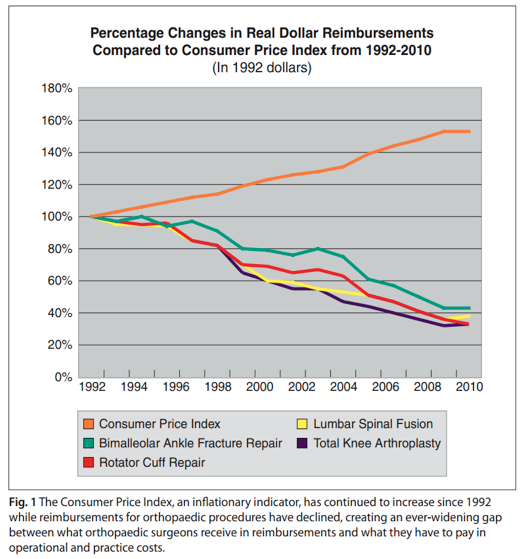

Payments lag behind inflation. According to a study by the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, the negative gap between what surgeons have to pay in operational and practice costs and what they receive in reimbursements has progressively widened. For example, a total knee arthroplasty (TKA) in 1992 would pay $2,102. By 2010, the reimbursement had dropped by 30 percent, to $1,470.45. A true “apples to apples” comparison, however, based on the value of 1992 dollars, finds that the reimbursement for a TKA in 2010 is equivalent to just $666.58—a drop of 68 percent.

Long training periods and sub-specialization reinforce provider’s belief that what they have been taught to do makes a difference. Research is focused on finding new ways to achieve that goal, and the endless pursuit of improving care combined with an aggressive entrepreneurial spirit encourages unbridled attempts at innovation. The exploration of new drugs, devices and procedures is welcomed by our consumer patients who want what is freely marketed as the “latest and greatest” – even when not yet fully proven to make any difference.

It has been long known that many innovations become costly failures to society. Providers who fail to provide what the medical industry is heavily marketing risk losing market share. High volume “thought leaders” are often the most business savvy providers who seek patients and services that provide the highest margin. The high costs of quality research almost demands company support which, of course, introduces bias toward studies that affirm positive results. Often when unbiased measurements are made later, the amount of difference made with many new technologies is small while the costs are substantially larger.

These business realities and extraordinarily complex regulatory requirements have challenged the sustainability of many medical practices. Small physician practices have been unable to compete with consolidating hospital systems whose enormous capital and political clout favor more corporate medical practices. For better or worse, employed-physicians who are beholden to their CEOs are also the main engines driving the funding sources for their corporation’s business interests.

The business interests can assume greater control of where and how they practice. System bias to do more testing to avoid missing a diagnosis or misdiagnosing an illness can be rewarded with substantial improvement to the bottom line while not improving a patient’s or population’s health. Missing a diagnosis doesn’t fall on the CEO’s shoulder, but it can raise the issue of professional competence. Providers (who are paid to order and interpret the tests) respond with an abundance of caution. It’s no wonder that delayed diagnosis, missed diagnosis, and even unhappy patients can generate intensively close scrutiny by “Peer Review Committees” (almost always formed by employees of the CEOs).

Patients often favor the over-testing which leads to over-diagnosis and over-treatment – often for things that won’t make a measurable difference to a patient’s health. It isn’t difficult to understand why “even reputable physicians with the best intentions tend toward overkill,” as Dr. Atul Gawande wrote last year in The New Yorker.

A growing focus on satisfaction scores that overshadow the changes in objective medical outcomes are strong nudges to worry less about making patients healthy and more about making them happy. Medical schools have long stressed the need to avoid excessive use of narcotics, unnecessary antibiotics, and the health issues associated with obesity. But it takes a brave doctor to engage in the discussion of weight counseling in the age of Press-Ganey satisfaction reports. A recent ProPublica piece discussing reviews of doctors on Yelp highlights the issue of linking quality to satisfaction:

“Health providers as a whole earned an average of four stars. But sort by profession and the greater dissatisfaction with doctors stands out. Doctors earned a lower proportion of five-star reviews than other health professionals, pushing their average review to the lowest of any large health profession, at 3.6. Acupuncturists, chiropractors and massage therapists did far better, with average ratings of 4.5 to 4.6.”

Chiropractors and masseuses may please patients but they are also protected from the burdens of evidence based medicine. Dollars spent on the temporarily passive pleasing of patients will not make a difference on changing the underlying chronic health issues of obesity, diabetes, cardiac disease, arthritis, or cancer. Many patients believe that more care is better care. A nationwide study in the Archives of Internal Medicine of more than 50,000 adult patients compared the health outcomes of patients by their satisfaction scores and found higher patient satisfaction was associated with “greater inpatient use, higher overall health care and prescription drug expenditures, and increased mortality.”

Current satisfaction surveys don’t measure the difference between a patient who a physician has decided won’t benefit from a pill, MRI, surgery or referral to therapist and a patient who is selected for treatment. A patient who is determined to be a poor candidate for surgery because of weight, smoking, or other medical conditions may be very unhappy that the doctor wouldn’t schedule him. But the doctor who provides an un-needed pill, treatment, or surgery will be financially rewarded and may have greater satisfaction scores.

Conservatives and liberals alike have blamed our country’s high medical costs on a system that’s based its reimbursements solely on the volume of services.. Despite having the most technologically advanced medical care in the world, we spend too many dollars on things that don’t make enough difference.

Experts universally agree that it’s time to focus on the value of the things done in medicine. Both parties in House and Senate signed on to repeal the sustainable growth rate, or SGR last spring. Key to this legislation is a focus on incentivizing the value of what physicians do instead of simply the number of things that they can do.

About a year ago, Health and Human Services Secretary Sylvia Burwell announced that 30 percent of traditional fee for service Medicare payments would be tied to value-based care models by the end of 2016 and raised the goal to 50 percent of payments by the end of 2018. The hard work of converting a system fueled by volume to one that produces routine high value care is going to require changing the way patients choose their care and the way third parties pay providers for their services.

But it’s hard to change players in a system where More Is Better and where the only profits come from the excesses possible at the margins. It gets even more perverse when incentives favor the new unproven, ‘hoped for’ innovations while well-studied treatments fail to break even or are unprofitable. Any efforts to reduce the wasteful care are confronted by claims of “rationing,” fears of “stifling innovation,” and, worst of all, “not being patient-centered.”

If we can’t afford to do everything that could possibly help anybody, then how do we decide the critical things to provide with the money we are willing to spend? What are the procedures that should be done? The answer is not always black or white. For example, arthroscopic meniscectomy of the knee— the most common orthopaedic procedure in the world— involves sticking a scope attached to a TV monitor into the knee and trimming out an unrepairable tear of the shock-absorbing cartilage of the knee. It’s true that a meniscus tear can cause severe symptoms that may be disabling knee stiffness (“a locked knee”), or a recurrent painful mechanical unsteadiness when the knee twists in the wrong position (“a trick knee”). But more often, the meniscus tear can cause no symptoms at all or only create a nuisance pain in the area of the joint line where the thigh bone meets the leg bone.

Patients in middle age and older frequently have both meniscus tears and arthritis. Both can cause nuisance pain or can be completely asymptomatic. When arthroscopy is done in face of both arthritis and a meniscus tear, it is not uncommon that patients are incompletely relieved of their symptoms. The difference made when resecting a “locked meniscus” is amazing. But it is not uncommon for a degenerative meniscus that is resected in an arthritic knee to make no difference at all. Surgeons get paid the same for the procedure in each scenario.

One piece of the “art of medicine” is selecting which treatment will make the biggest difference for our patients. Surgeons are not surprised that a young depressed obese female with moderate arthritis related to a workplace injury may not do as well as a thin elderly successfully-retired grandmother brought in by her family with severe disabling end-stage “bone on bone” arthritis. A substantial difference is almost assured for Granny but the other patient’s outcome—even with a technically exceptional procedure—may be disappointing. Surgeons actually get paid more in the current system for the young person’s surgery even though the surgery will likely make less of a difference.

Should society pay for the surgery for each scenario? Or just the surgery that removes disability? The answers depend upon who you ask and when. Denying access to arthroscopic surgery to fix a “locked knee” is untenable to most professionals. Paying to resect every meniscus tear that can be found will break the bank. But to whom does society say no? The choices will have to be based on evidence for “the house of medicine” to ethically sign on. By incentivizing patients to routinely report the difference made, we can create the evidence which shows: who does the best from a surgery, which surgeons are improving the outcomes the most, and which procedures create the greatest improvements in health. This process is called collecting “patient reported outcomes”.

The FDA defines a Patient Reported Outcome (PRO) as “any report of the status of a patient’s (or person’s) health condition, health behavior, or experience with healthcare that comes directly from the patient”. In Orthopaedic surgery, the best measures are symptoms or issues that affect quality of life like the ability to walk a certain distance or open a jar. To compare these various “domains” of outcome, we need a standardized tool to measure the outcome (called a “PRO measure” or PROM). Common PROMs for pain include the “Verbal Rating Scale” (VRS: none, mild, moderate, severe) or a “Numeric Pain Rating Scale” (NPMS), which is simply a line with numbers from 0 to 10 that can be marked to assess pain.

Surgeons are especially proud of the difference we can make. Because surgery is an expensive form of care, measuring the differences in outcomes each of us makes for each case performed will provide worthy feedback to society, our patients and ourselves. Surgeons themselves should select the tool used to record the measurement, but for each procedure one set of tools must be selected and used by all the surgeons who perform that surgery.

Surgical subspecialty medical societies are the best venue through which we can debate and select which Patient Reported Outcome Measure best sums up the difference each surgical procedure makes. Primary care doctors may be better measured on the preventative services their populations receive (percent immunized, percent screened for cancer) and global measures of the risk-adjusted costs incurred for their population. But whatever they are measured on, primary care organizations like American Academy of Family Physicians and the American College of Physicians should pick the outcomes for their members. Forcing “organized medicine” to get organized in a timely fashion is one of the hurdles.

It is well known that most of the determinants of health have little to do with doctors or hospitals. An individual’s genetics, psychosocial situations, personal health choices, living, and working environments all factor into to a patient’s health and outcome. The balancing of all these issues is the true “art of medicine” and is crucial in making a difference for an individual patient. Incentivizing patients to be engaged in their own health care is critical and depends on their level of education, financial status, and health status. If we want patients to be engaged in their care, we need agreed upon credible reporting of the evidence to guide them.

Without a formal “report card” on the specific outcomes the patient of these physicians experience, we can’t tell if a higher number of services and/or higher-than-average costs are making more of a difference for patients than the doctors who are more frugal and sparing. Linking patient-reported outcomes to the expenses associated with those outcomes should be required before honest and ethical decisions can be made on what is high value care.

It will be a bit of a challenge, but not an impossible task to deliver. In fact, measurement techniques already exist. The National Institutes of Health has developed a computer adaptive patient reported outcome system that keeps the testing burden low (fewer questions asked each patient to get an assessment) and can generate results that can be compared between diseases and disorders. Doctor’s offices already have to pick diagnosis codes and treatment codes as well as their charges to get paid. By combining all these together in a large database, or “registry,” society will be able to see which treatments and doctors make the most difference.

Dr. Marc M. DeHart, MD is an Austin-based orthopaedic surgeon. He is a Board of Councilor with the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons and served as president of the Texas Orthopaedic Association from 2014 to 2015.