Programming Note: Matt Goodman, D Magazine’s Online Editorial Director, will be in conversation with Megan Kimble at 6 p.m. on Wednesday, April 10, at Interabang Books. Find more information here.

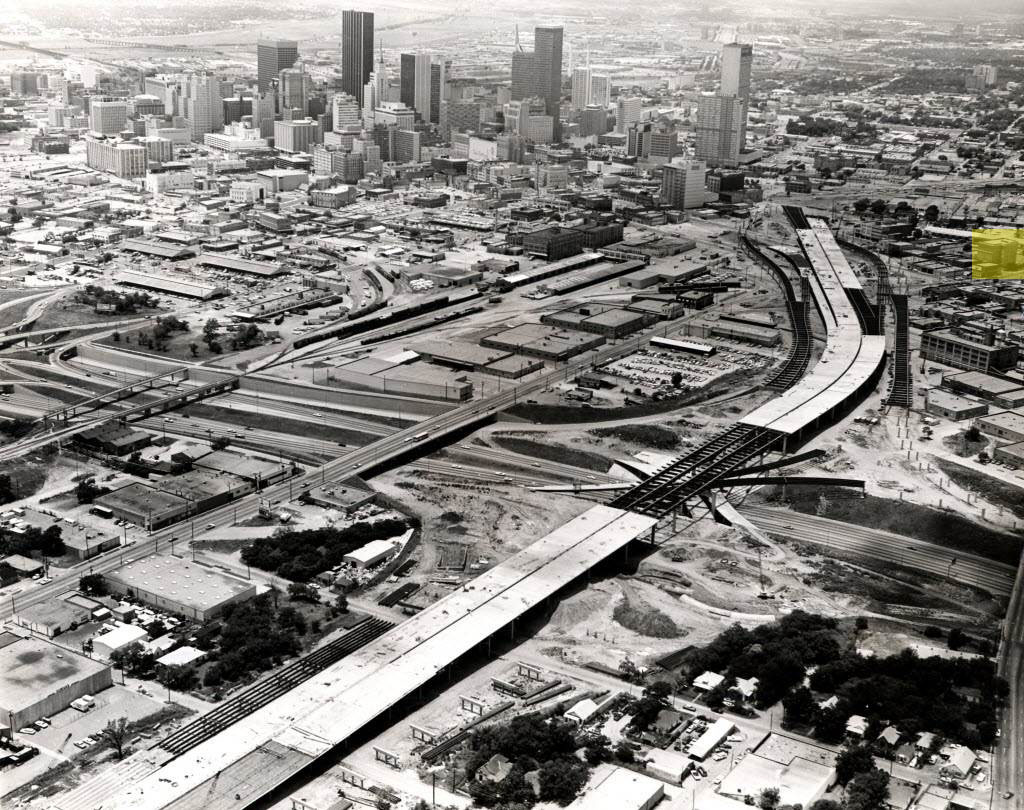

The history of Texas highways—and across the nation, really—is fraught with examples of how these enormous capital projects have damaged cities. In Dallas, 1944’s Federal Highway Act and 1956’s Interstate Highway Act produced highways that made it faster to move from point A to point B, but also cut off entire Black and Brown neighborhoods and communities from the rest of the city, enveloping them in traffic noise and polluted air.

This month, Texas journalist Megan Kimble’s book, City Limits: Infrastructure, Inequality, and the Future of America’s Highways, looks at three different communities and their fight to have more say in how the Texas Department of Transportation envisions their neighborhoods. Kimble looks at the impact I-10, I-35, and I-345 had on Houston’s Fifth Ward, East Austin, and Deep Ellum in Dallas, respectively.

The book could have become a wonky slog, but Kimble deftly weaves the stories of the residents who joined the fight into the narrative. Dallas readers will see familiar names (including D’s own Matt Goodman and DART board member Patrick Kennedy), but more importantly, they’ll see how the three stretches of highway are intertwined.

It’s a smart, compelling read that raises questions we should all be asking, whether our homes are adjacent to a highway or not. What would Dallas look like if I-345 had never existed? How do we get past the siloed expectations of each entity involved: TxDOT’s mission to move cars, the regionally-minded priorities of the North Central Texas Council of Governments, and Dallas’ economic realities that dovetail with its relatively new racial equity, climate, and land use plans?

Kimble also homes in on the fact that when the federal interstate system was initially planned, there was a push for a more thoughtful approach. President Dwight D. Eisenhower had tasked Gen. John S. Bragdon with researching plans. Bragdon’s findings, if they had been followed, would’ve meant something much different for Dallas, Austin, and Houston.

“We do not believe that the Interstate System is the vehicle for solving rush-hour traffic problems, or for local bottlenecks,” Bragdon said in his report. “Rapid transit and mass transit systems are the solution.” He argued that communities should not develop around highways but should be developed through economic growth and land use plans. Bragdon pointed out what has become a familiar refrain during current discussions about TxDOT’s plans—the bigger the road, the more people travel on it, the more traffic increases.

Although Eisenhower agreed, the plan was shelved when local leaders nationwide were extremely bullish on the growth they thought highways would bring to their cities. Although highway budgets have grown, federal and state dollars for public transit have not kept pace.

There is no truly happy ending in Kimble’s book—I-345 doesn’t become a walkable boulevard; I-35’s expansion continues, forcing a beloved and vital childcare facility to move; and Houston’s Fifth Ward is still transected by an ever-expanding highway. But earlier this month, we spoke to Kimble, and she says there is a bright spot—more and more residents are finding more effective ways of pushing back.

“I feel both encouraged and discouraged, if that’s possible,” she said. “The body responsible for all these decisions is ultimately the Texas Transportation Commission and, until recently, I don’t really think there was activism focused there. So the fact that over the last four or five years activists have started showing up at the Transportation Commission meetings asking for something else … to me, that’s where change will happen—at the state level.”

More of our conversation, edited for brevity, follows.

Do you feel like there was a common thread among the stories about the community activists in each of these cities, other than that they didn’t want TxDOT’s plans for those highways?

I didn’t really understand how much power the state has and that, really, the fight for better transportation needs to go to the state. The activists certainly have realized that, so it was actually really fun to watch. When I started reporting on this in 2020, the activists in the cities were not really talking to each other—the activists in Dallas, Houston, Austin, and San Antonio had their campaigns against particular highways. And I watched as it coalesced into a much more statewide movement. I think there are now monthly or biweekly Zoom meetings where people from across the state talk to each other. They plan these coordinated protests at the Texas Transportation Commission.

It’s not necessarily surprising, but kind of unexpected and really kind of cool to see. As a reporter, I had this realization that all these highway expansions are happening across the state, and there’s media in Houston talking about it. The media in Dallas talking about it. But what’s the entity behind all of this? What’s the statewide engine driving these expansions across the state? So let’s look at TxDOT. Let’s look at the Transportation Commission. And the activists have had that same kind of movement to look at the state.

One of the meetings you wrote about, I remember covering too. And I remember a council member asking what TxDOT’s projections were based on—how people in southern Dallas travel to work now or future plans that might also include more work opportunities and amenities where they live. Is that a blind spot for TxDOT, or just not a factor?

This could get really wonky. (Laughs.) I think it’s more than a blind spot. I think they put on blinders. TxDOT doesn’t consider land use. They don’t model based on projected land use changes or where people will live. They basically say here’s the number of cars today, here’s the population growth. We assume this many people will come with this many cars. Therefore, let’s spit out the number of cars on the road, and we have to accommodate that. I haven’t seen their models—their traffic models are famously a black box. But the models are presented as absolute truth when they are, at best, projections.

I’ll circle back to Dallas in a minute, but when I think about it, it makes me very angry. For instance, the environmental documentation for the I-35 expansion in Austin—there’s this little chart that basically compares travel times today, travel times in 2035, and travel times in 2050. And it’s the stretch of highway that goes right through Austin. It’s eight miles and should take eight minutes to drive, which I think is ludicrous. It’s one of the fastest-growing cities in the country—why should we be able to get across it in eight minutes? But then they say if we don’t expand this highway in 2050, it will take 223 minutes to travel that distance.

TxDOT doesn’t consider land use. They don’t model based on projected land use changes or where people will live.

Megan Kimble

That’s like three and a half hours. I could walk the length of I-30 faster than that. But they present that as fact that, in the future, you will be stuck on the highway for three and a half hours to travel across the city. The reality is that people will change their behavior, and they will either live somewhere different or they will work somewhere different. They won’t take that highway. I think that is just so revealing how ludicrous the assumptions that go into these models are.

In Dallas, it’s similar. TxDOT certainly could say, ‘Hey, city of Dallas, what are your housing projections? Where do you want people to be living in 2050, let’s incorporate that into our models,’ because maybe there’s going to be less demand coming from, say, Richardson or wherever. They certainly have that capability, and they’re just choosing not to.

Dallas is also working on a land use plan. It’s been slow-going. And I can’t help but wonder if this plan had already been in place when TxDOT came to town to talk about I-345, the conversation might have gone at least a little differently. Would it be different if these cities already had comprehensive land use plans to point to, to say, ‘No, look, that doesn’t go with our very concrete plans here,’ as opposed to some kind of ephemeral idea of what they might do?

I totally agree. I mean, I started reporting this in part because I wrote a long story for the Texas Observer about Austin’s attempt to update its land development code and allow for more dense housing. There’s a huge demand for that in Austin, but we have this very antiquated land development code. And then three months later, TxDOT allocated $4 billion to expand I-35. It’s very much the same story: Austin couldn’t get it together to allow more dense development, so TxDOT comes in and says, ‘Obviously, we need to expand this highway to allow for more people to come in from the suburbs.’

So I do think cities are somewhat culpable in the sense of land use, zoning reform, and comprehensive planning. If there was a better and more concrete vision coming from a city like Dallas or Austin, they could go to TxDOT and say, “Hey, we’re gonna do everything in our power to make it so that people aren’t on that highway.” I think there would be at least a little more leverage.

The most recent Census figures aren’t great for the city of Dallas, either. Regionally the area is growing, but that growth isn’t in Dallas proper.

You know what surprised me—I learned that from Patrick Kennedy, and I didn’t know before, but there is this narrative that North Texas is booming, Dallas-Fort Worth is booming, leading the nation in job creation and population growth, etc. But that’s the suburbs. TxDOT has these origin of destination studies, and there is certainly a lot of movement north-south across the city. I think mostly it’s people coming from southern Dallas going north to work, right? I actually don’t think it’s people from North Dallas going downtown or to South Dallas.

But TxDOT isn’t obligated to consider any of that. They have traffic models. They have traffic projections, and that’s really the only thing they are obligated to consider. You can see that when you read a lot of the “purpose and need” portions of these projects— it’s like safety and traffic congestion are the reasons.

And that’s been true since the beginning. Highway agencies don’t have to think about urban planning, even though it’s so abundantly clear that highways have a huge impact on how cities develop. There’s no obligation. Even if Dallas had a stronger vision for itself, it would probably help, but TxDOT doesn’t have to listen.

Author