At the end of the month, the Dallas City Council will consider repealing a section of the city’s development code that many preservationists say is single-handedly responsible for the demolition of over 70 structures in the former freedmen’s town of Tenth Street.

Almost any resident in the Tenth Street Historic District can recite the code’s number: 51A-4.501(i). But most refer to it by the more direct name of “the 3,000-square-foot rule.” Passed in 2010, it’s a section of the Dallas Development Code that allows for the demolition of homes smaller than 3,000 square feet within a Landmark District, a designation that layers specific design guidelines and preservation criteria meant to protect neighborhoods deemed historic.

At the time, 14 years ago, residents and the Landmark Commission warned that the rule could have detrimental effects on many of the city’s most threatened older neighborhoods, especially those founded by Black residents. (The Landmark Commission considers certain changes to existing structures these areas, which are then voted on by the City Plan Commission and the City Council.)

Between 2010 and 2023, the city says that 35 historic homes were demolished in Tenth Street, which is located just east of Interstate 35 in Oak Cliff, and six were demolished in Wheatley Place near Fair Park. A 2019 lawsuit filed by the Tenth Street Residential Association alleged that the true number of demolitions was closer to 72 of the neighborhood’s 260 total homes.

Most homes built in historic freedmen’s towns like Tenth Street, Joppa, and Wheatley Place are smaller than 3,000 square feet. Many of the home demolitions were done at the city’s request because of their condition. A 2019 moratorium stopped the city from using public money to tear down the old homes.City staff is ready to get rid of the language, but will need approval from the City Council.

“The default for these homes became demolition, rather than consideration for rehabilitation,” assistant city manager Majed Al-Ghafry wrote in a memo about the matter last week. Al-Ghafry told the Council that there are still mechanisms for demolition in historic districts. The 3,000-square-foot rule, he said, “is unnecessary and has in effect, resulted in unintended consequences and disproportionate impact on communities of color.”

But to appreciate how this ordinance impacted Tenth Street, it is important to understand how Tenth Street and neighborhoods like it have contributed to the city’s history. Local, state, and federal policies over the last century have resulted in decades of displacement and disinvestment. The residents who are fighting this ordinance believe they are fighting for what is left of Tenth Street’s history.

Present-day Tenth Street is bounded by Interstate 35, East Eighth Street, and Clarendon Drive at the eastern edge of Oak Cliff, not far from the Dallas Zoo.

But it began in the 1880s, south of the Trinity River, when formerly enslaved people from the plantation of William Brown Miller settled in what was known as “Miller’s Four Acres.” By 1888, previously enslaved people from other states began buying lots and homes. By the turn of the century, Tenth Street was a busy, bustling community with churches, a school, and small businesses started by the families who lived in the neighborhood.

“It’s the genius of the African-American freedman, and it’s about the triumph of the human spirit. It’s at the intersection of man’s faith and God’s providence,” says resident Larry Johnson. “You have people that came from the slave fields and they ended up owning properties—I think one guy owned like 10 properties. How does that happen?”

Johnson, a member of the Tenth Street Residential Association and a representative on the Landmark Commission’s Tenth Street task force, says Tenth Street offered the sorts of things that are lauded in land use discussions today in Dallas.

“Tenth Street was a mix of incomes. You had doctors and lawyers living next to janitors and horse washers and car washers, blue-collar living next to white-collar,” he said. “It didn’t really matter.”

His home was originally owned by the Vickers family, who purchased it around 1917. “There was a pretty famous local artist that lived in the house, Ruth Vickers,” he says. “I actually found some of her artwork in the house. They’re at the African American Museum in Fair Park now.”

Every house still standing, he says, is full of stories. But Jim Crow-era policy began to change the fabric of the community, says Robert Swann, a Tenth Street resident who, until recently, sat on the Landmark Commission. Swann and Dallas City Plan Commissioner Joanna Hampton wrote extensively about the neighborhood’s history for AIA Dallas in 2020.

Swann says that at one point in the early 1900s, some streets had blocks where both Black and White residents lived side-by-side. But in 1916, 15 years after Dallas annexed Oak Cliff, a city referendum allowed officials to separate blocks by the race of the homeowners. While that ordinance was overturned by the Texas Supreme Court the following year, a similar ordinance was passed in 1921 that allowed residents in a neighborhood to determine whether their block was White, Black, or open.

Swann said that policy meant that the neighborhood went “through an evolution.” He said one family moved their entire home from its lot when the block they lived on was deemed a White block.

“The house was moved from the corner of Cliff and Eighth to East Ninth so that they could keep their home,” Swann said.

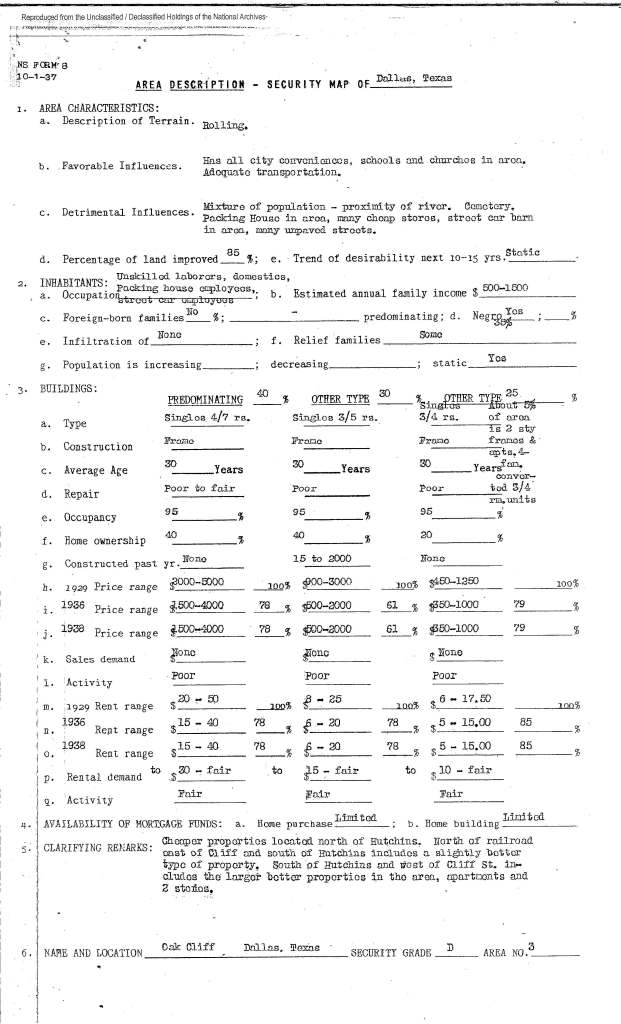

Johnson said this policy only made it easier for Tenth Street to become redlined when the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation, or HOLC, created maps that designated a neighborhood’s desirability and risk for mortgages in 1936. Redlined areas were almost exclusively Black, and few, if any, would lend to prospective buyers. Disinvestment by the city followed.

By the 1960s, I-35 was routed through the neighborhood, cutting it off from the rest of Oak Cliff while demolishing homes and businesses. By 1993, the community was struggling to protect its historic homes. It received its Landmark designation that year, but it wouldn’t serve as a protection—residents say even more homes came down in the ensuing years.

In an October 2018 Landmark Commission meeting, city staffers faced off against commissioners who refused to approve the demolition of a home at 1105 E. Ninth Street. Swann, who was on the commission then, said the case “turned the tide.”

The home was built by William Smith, the son of a formerly enslaved person, in 1910. It stayed in Smith’s family until 2005 and had been vacant for at least a dozen years.

Johnson told commissioners that the house should be saved.

“There is a time to go by the rules, and then there’s a time where rules must be broken for different reasons,” he said. “We are one of the only intact freedmen’s towns in the state of Texas, and one of a few in the United States of America.”

Suddenly, commissioners began speaking up, one by one, to question whether this house—and others like it—needed to be torn down. It was a formal challenge to the city’s longstanding ordinance.

“Does Dallas realize that they’ve got a diamond in the rough with having a freedmen’s town?” asked Commissioner Don Payne. “Will Dallas realize what it has in the Oak Cliff area?”

The commission voted 8-6 to deny the demolition. It became one of the first times the commission defied the city. Swann says the City Plan Commission followed the recommendations of the Landmark Commission when city staff would ask for permission to demolish structures in Tenth Street.

Soon, the City Council got involved. In 2019, the district’s council member, Carolyn King Arnold, organized a successful effort to halt using city funds for Tenth Street demolitions. In May of that year, the National Trust for Historic Preservation included Tenth Street in its annual list of the country’s most endangered historic places.

A few months later, the Tenth Street Residential Association sued the city to eliminate the ordinance, arguing that the practice discriminated against Black neighborhoods and violated the federal Fair Housing Act and the Equal Protection Clause. That suit went to the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals, which ruled against the association in 2020. But in the years since, City Hall has changed its stance and wants it gone, too.

In a meeting last month of the City Plan Commission, Kate Singleton, Dallas’ chief preservation planner, outlined why the Landmark Commission had asked the body to rescind the ordinance. Singleton said city code would still allow for the demolition of unsafe structures. The city is now recommending removing a provision that most affects Black neighborhoods.

“These regulations actually impact about 90 percent of the houses in the 21 historic districts that are 3,000 square feet or less,” she told commissioners. “Once you start demolishing in a neighborhood, the only thing that happens is more demolitions.”

Singleton also said that from the moment the ordinance was initiated almost 15 years ago, the city preservation staff, the Landmark Commission, and other preservation advocates in the city “did not want this subsection.”

Several commissioners questioned why the city took more than five years to rescind the language in the ordinance. “We don’t have any more to lose,” Johnson said. “Every other home is being lived in for the most part.”

Johnson said he believes the city owes residents for the present state of Tenth Street and neighborhoods like it.

“The 3,000 square foot rule and redlining are two of the main reasons why I believe Tenth Street and places like Tenth Street—we’re owed reparations in the form of land going to reputable builders,” he said. “Builders that have a track record of building historic structures and being respectful to the neighborhood they’re building in.”

He’d like to see the city invest directly in the structures that once held the lifeblood of his community: the small businesses. He’d like to see the city audit its land bank, and make sure that developers are actually building on the land it purchases from the city in a timely fashion.

He’d also like to see new ordinances that make it easier to relocate a historic home to another plot of land. He’s done the math; it can cost him roughly $30,000 to move a historic home five minutes away to land he owns elsewhere in the neighborhood. But the companies he’s approached have warned him that the city’s process for moving a structure is arduous.

“The city of Dallas needs to make that easier for guys like me or for other people who want to move a house in,” he said. “People are demo’ing these houses like crazy. We can preserve them, and the city should back preservationists.”

Johnson and Swann expect the Council to approve the change to the city’s code. I asked candidates about the ordinance when covering the City Council elections in 2019 for another publication. Two candidates are still on the Council: Adam Bazaldua, in South Dallas and Fair Park, and Paula Blackmon, near White Rock Lake. Both agreed that the ordinance was not applied evenly across the city and said they supported changing it.

“When this ordinance is applied across the city, this negatively affects our historic districts in lower-income neighborhoods where we are working to preserve not only the structures but also the heritage and culture of that community,” Blackmon said then. “These communities have remarkable achievements built on culture and it harms those that continue to reside in these historic districts.”

Council is scheduled to vote on the matter during its February 28 meeting.

Author