Updated on 1/5 to clarify what voters approved in 2022.

Cranes can be seen between the trees in the communities surrounding Fair Park. New apartments, retail, and public infrastructure improvements are coming adjacent to the amenity that is most commonly used during the three weeks of the State Fair of Texas.

Developers and policymakers regularly hold community meetings to solicit input from longtime residents and community advocates. These stakeholders watch the activity with a mix of excitement and wariness. They’ve been here before, staring down changes that will leave South Dallas in a very different state than it is today. The realities of what followed the previous talk of progress tested their resilience time and again.

Historically, progress in Fair Park has rarely benefited its neighbors. So will this time be different?

The most obvious change to the neighborhood is the highway. Interstate 30 was routed through this part of the city in the 1950s, cutting it off from the rest of Dallas. The freeway’s construction displaced residents and made it difficult for those who remained to use public transportation; the highway eventually contributed to the demise of the city’s robust streetcar system. Its placement sharpened the divide between northern and southern Dallas.

Later, the city expanded the park’s footprint, growing from its 80-acre beginnings in 1886 to its current 277 acres. The progress once again came at the expense of the wood-frame houses owned by Black families. In the ’60s and ’70s, the city offered those families much less than what they paid for those homes, sometimes as little as 65 cents per square foot. White property owners typically received more than four times that amount.

Trying to mend the city back together in a way that it was once before—that’s a challenging notion.

John Spriggins, resident and General Director of the South Dallas Cultural Center

The impact from that decision changed the makeup of the surrounding neighborhood and its relationship with Fair Park, which contributed to the city’s decision to privatize the park’s operations in 2019. A new nonprofit called Fair Park First was awarded the keys and embarked on an ambitious plan to at long last connect the fairgrounds with the neighborhood by way of a new community park. The nonprofit aims to make the park a year-round destination while preserving the country’s largest collection of Art Deco buildings. It is also attempting something that might be impossible: righting the wrongs wrought by former city policy and development.

We spoke to developers, residents, community advocates, a city official, and those steering the improvements at Fair Park about the momentum building just outside the fairgrounds. All agreed that if the plans come to fruition, the Fair Park of today will look quite different in five years. Whether this new vision is positive, they say, depends on the city’s commitment to improving the community and whether it truly desires to not repeat the wrongs of the past.

Removing a Barrier

It was no accident that I-30 was routed through Black neighborhoods, severing Exposition Park and Fair Park from the rest of Dallas. Between historic redlining and the bombings that followed when Black families moved into what had been White neighborhoods, safe housing for Black families in Dallas was scarce. But that wasn’t considered a factor when the federal government decided Dallas needed a new highway.

“One of the issues that is difficult for contemporary observers to grapple with is how intentional these demolitions in African American and Hispanic neighborhoods were,” Dr. Kathryn Holliday, an architectural historian at the University of Texas at Arlington, once wrote. “It is critical to understand that they were indeed intentionally targeted for demolition, both through racist national policies established by agencies like the National Highway Administration and discriminatory state and local policies that targeted the poorest and most disenfranchised populations.”

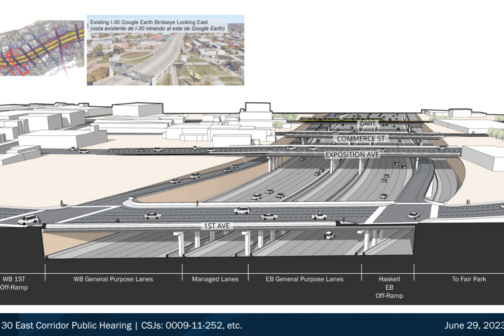

The partially elevated highway has stood between South and East Dallas ever since. But the Texas Department of Transportation in 2021 announced plans to bury I-30 from downtown to Dolphin Road in East Dallas. The agency said it hoped to reconnect streets and communities, especially in Fair Park and South and East Dallas neighborhoods like Jubilee Park and Dolphin Heights.

TxDOT will widen the highway, adding a lane in each direction and a managed lane down the middle, as well as a potential deck park. Sidewalk-lined streets will fly over the highway. The project will require some land acquisition, but the agency says that total acreage is small compared to how much land will be freed up as ramps are demolished. The state has allocated at least $524 million to the $1.02 billion project already, and TxDOT said in June it anticipates beginning the bidding process for construction in 2027.

But work is already beginning. The agency has been acquiring land and working on preliminary design plans, important checkpoints to show that the project is shovel-ready and worthy of additional funding. And as work on the highway begins, private development has finally come to Fair Park’s door.

Larkspur Capital president Carl Anderson, who has several multi-family and mixed-use projects in the works near Fair Park, anticipates the project will enhance his holdings.

“It’s going to change the whole dynamic,” he says of the freeway plans. “I think that will really help reconnect these neighborhoods. This is just a game-changer for the whole area—it’s going to change the makeup of Fair Park and help accessibility. The streets are going to be realigned and fixed.”

The developer says that Larkspur has been working with TxDOT for several years now because their projects are adjacent to the I-30 project.

“What they’re telling us is, ‘Hey, we’re doing a better job on this than we did on Central Expressway,’” he says, referring to when that highway was placed below grade near downtown. “And because of better city planning and just the philosophy being more pedestrian-focused, it’s not going to be like when you try to cross Central—this has very wide, protected sidewalks and is very pedestrian-focused, which is great to hear.”

Dallas City Councilman Adam Bazaldua, whose district includes the Fair Park area, says he “100 percent” agrees with Anderson, but he also knows that it will bring even more attention to the location.

“We could easily be complicit in perpetuating exactly what we’re trying to avoid.”

Councilman Adam Bazaldua

“It also means that it’s important that we understand what that impact will bring if we don’t have our ducks in a row before that project is complete,” he says. “We could easily be complicit in perpetuating exactly what we’re trying to avoid.”

Building Momentum

As TxDOT works on its plans for the highway, private development has begun sprouting near Fair Park. Larkspur Capital LP is behind much of that momentum, a Dallas-based firm that says it focuses on “urban renewal in transitional neighborhoods.”

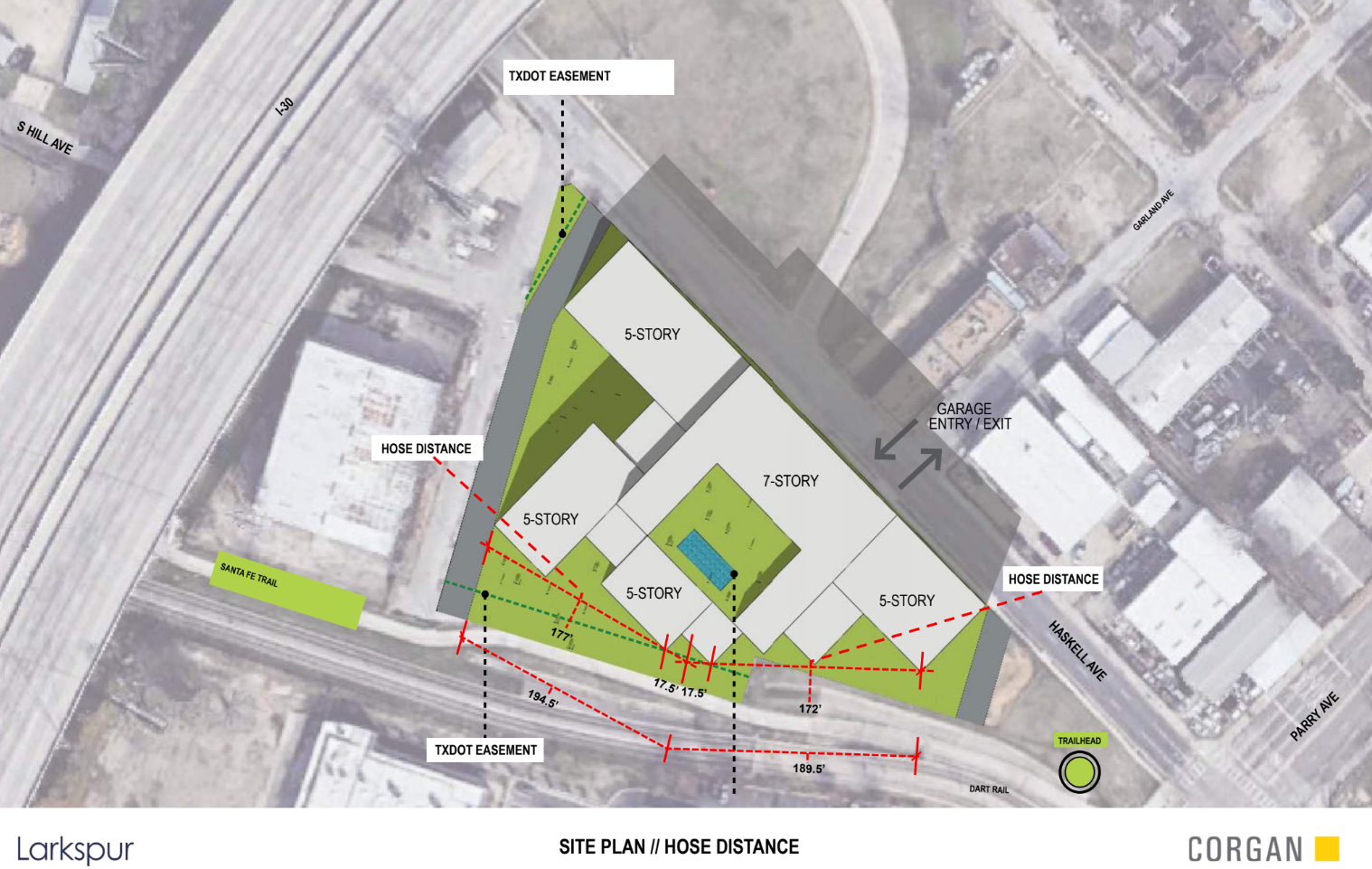

Larkspur just completed an eight-story apartment complex called The Willow this summer on Commerce Street at the edge of Deep Ellum. At the other end of the same block, Larkspur has planned a five-story, 220-unit development called The Juniper. Their neighbor is the presently elevated I-30; this area is where TxDOT plans to sink it below ground. Across I-30, Larkspur is planning a half-acre private park, trail access, and ground-floor retail. Another 240-unit complex is planned for Haskell Avenue closer to Old East Dallas and the soon-to-be extended Santa Fe Trail.

A 290-unit project on Second Avenue and Ash Lane has generated a lot of interest from the neighborhood. Situated between Exposition Park and Fair Park, half of its units will be set aside for much-needed workforce housing, while the other half will rent for market rate. It will include more than 400 feet of frontage along the Santa Fe Trail.

Anderson says that his team meets with the neighbors and tries to be respectful of the history of the Fair Park neighborhood. Their newest project will include elements that nod to the Art Deco buildings found throughout Fair Park.

“We’re providing a couple of units in this project to the South Dallas Cultural Center for its artists in residency program, too,” he says.

John Spriggins, the general director for the South Dallas Cultural Center, says that while nothing is set in stone regarding a potential artist residency, he came away feeling positive about his meeting with Anderson. He’s excited about the prospect of including housing in the SDCC’s Juanita Craft Artists in Residency program.

“We have space for artists to work here at the cultural center, but we don’t have living space,” he said. “What I think this would do is open up the opportunity not just for local artists but for us to expand our reach and be able to invite artists from around the state and across the country.”

It’s a cause near and dear to his heart because, at one point, he was an artist-in-residence at Southside at Lamar by way of a similar initiative led by development firm Matthews Southwest in the Cedars. He credits that program as being at the forefront of the local effort by developers to support the arts by providing working and living spaces for artists.

“I would definitely hope that there’s an appetite for whatever development that comes to the South Dallas community, that there is a thoughtfulness around how the arts community can be supported,” he says. “Carl was gracious enough to come sit with me and chat and tell me a little bit about what they’re doing…and what I wanted to do, and I very plainly told him that if we’re going to grow our residency program, we need living space.”

This is also an Opportunity Zone, which helps make this work. Combining it with the workforce housing component, we thought, makes sense all day long.

Carl Anderson, Larkspur Capital president

Anderson says a variety of factors make investing near Fair Park attractive. The company’s latest project received City Council approval for a public facility corporation designation, which gives Larkspur tax breaks in exchange for including affordable units in the project. The agreement between the city will require Larkspur to offer 146 of its 290 units to households earning 80 percent of the area median income, which is just shy of $64,000 for a single earner. That would make the rent between $1,200 and $2,000 a month, depending on how many are living in the apartment.

Rent based on 80 percent AMI is considered workforce housing that would be affordable for people like nurses, teachers, firefighters, and police officers. (It is around $49,850 for a single earner and $71,200 for a family of four.)

“This is also an Opportunity Zone, which helps make this work,” Anderson says, referring to the federal economic development program that provided tax breaks to developers working in designated areas across the country. “Combining it with the workforce housing component, we thought, makes sense all day long.”

Councilman Bazaldua says hopes Larkspur’s plans attract other developers open to offering workforce housing.

“Those are huge steps in the right direction,” he says. “They were willing, and they were completely on board with that, and to me, that sets the tone and really makes it clear that yes, we absolutely know that we’re going to have to be mixing incomes. We’re going to have to bring in some market rate.”

And with new office, retail, and restaurant developments in the area, Anderson says he is excited that others are seeing the neighborhood’s character. He points to the portfolio of buildings August Real Estate just purchased in Exposition Park as an example.

“This is such a neat collection of 1920s buildings. Those blocks are so neat just to walk down because they’re treelined, and the facades of the buildings have been maintained so well, but when you walk in these buildings, they’re much bigger than they look on the outside,” he says. “There are architectural studios and landscape architects—and you walk in there, and it’s just this little storefront, and then it gets bigger because these buildings have been reconfigured over time, and there are 50 architects in there pounding away in the middle of a sleepy, kind of overlooked area.”

August Real Estate, helmed by brothers Evan and Jordan August, had already made investments in nearby Deep Ellum, which included rehabilitating the Continental Gin Building. More recently, they purchased 17 buildings across 9 acres that total 400,000 square feet of commercial and residential space near the main entrance of Fair Park. They plan to improve the spaces within those buildings, which are currently leased to small businesses, artists, and residential tenants.

Evan August says that while the company is “just getting our arms around” their new purchase, they found that the investment was a good one because loft apartments are “easier to finance” and offer less risk. The opportunity to own several contiguous acres was attractive.

“There is so much we can do with that. We can create a little district and control our own destiny over time, adding amenities,” he says. “It’s creating the next little pocket of town that has a personality, and hopefully Expo Park becomes something that people, when you say it, know exactly what that means.”

The team plans on being intentional and careful with the property, too.

“At Expo, we control all four corners—there’s no other owners in the way,” he says. “There’s not a block where we’ve got some owner that’s just gonna, not renovate or not cooperate. We control it all.

“If all goes well, three to five years from now—and beyond—this area will continue to benefit from what we plan on doing.”

Anderson sees an opportunity for placemaking in the parking lots scattered about the area. He also sees potential for public-private partnerships that would make better use of city-owned land. The goal, he says, is to generate incremental growth that benefits people who already live in South Dallas while attracting others who would want to.

“This doorstep to Fair Park could be so much more welcoming and inviting than what’s here, and I think this wasteland of parking lots helps form people’s perception of the area in a negative way,” he says.

He says they also attempt to ensure that their buildings fit in with their historic surroundings when they build.

“We’re trying to build this in a way that respects the architectural context of the area and use materials that stand the test of time,” he says. “If you look at the projects we build, most of them are long-term holds for us—eight of 10 are, which is different than most developers. We’re going to own this—and in Opportunity Zones you have to— for at least 10 years. And my goal has been to hold on to them as long as our partners want to stay in.”

He says that the project at Ash and Second has turned the heads of other developers, too.

“I think it already has spurred more interest in the area—there are other developers poking around now that I’m hearing about,” he says. “And hopefully, that spurs more development deeper in the neighborhood.”

A Catalyst …

When the city sought to privatize operations at the 277-acre park and appointed Fair Park First to do so, the mission was clear: raise money, involve the communities around the park in developing a new master plan, and manage capital improvements among the old Art Deco buildings.

It got started with a boost. Voters in 2022 approved setting aside $300 million from a two-cent Hotel Occupancy Tax increase for renovations to the Cotton Bowl, the Coliseum, the Band Shell, the Centennial Building, the Automobile Building, and the Music Hall. The vote provided Fair Park First some relief for fundraising, freeing up more of its donor money to be spent on an 18-acre community park that will reclaim parking lot space that was taken from Black homeowners through eminent domain decades ago.

Those improvements—as well as efforts to bring more activity to the park during the 49 weeks the State Fair isn’t in operation—are also attractive to development. Luallen, the head of Fair Park First, says he sees this as a double-edged sword.

“We’re really cognizant of that history,” he says of the city’s use of eminent domain. “We spend a lot of time in the neighborhoods, and I think it’s really exciting to see that there’s a lot of critical mass that seems to have really come together in the last couple of years.”

Luallen points to work happening elsewhere in the neighborhood, like the nearly $22 million infrastructure improvements for Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard and the removal of S.M. Wright Freeway. Community development corporations and organizations like Forest Forward are providing both public and private investment in the area. There is also a planned extension of the Santa Fe Trail that will wrap around Fair Park and connect to the Queen City neighborhood.

“That’s really good investment that will promote better health outcomes and more,” he says. “I certainly understand a lot of private developers watching that and saying, ‘Now’s the time.’”

Jason Brown lives near Fair Park and works in the community as the CEO of Dallas City Homes, an organization whose goal is to create and preserve affordable housing. He also serves on the boards of Fair Park First and the Grand Park South TIF District.

He says that an array of old plans that didn’t come to fruition has helped propel Fair Park First’s progress.

“You had all these different plans for the MLK corridor and Fair Park…all these ideas and talk, but nothing actually had a budget, any feasibility, or due diligence,” he says. “They’re just sitting on a shelf. So we just started putting stuff together that was already there. This is a national treasure, but how do we connect the dots?”

My sort of nightly prayer is always, you know, ‘let us do good but let us also do no harm.’

Brian Luallen, Fair Park First CEO

Luallen says that while previous attempts to attract growth to southern Dallas “didn’t quite catch,” a larger wave of activity that includes the Southern Gateway Deck Park and Red Bird Mall in Oak Cliff feels like “there’s now a tide that can’t be stopped.”

The renewed interest in the area makes it “an exciting time” for Brown and his neighbors.

“For years, you’ve heard the talk, and finally, you’re starting to see something,” Brown says. “I’m talking about folks who grew up in the area who knew what it was when we had four or five grocery stores—and this was not that long ago.”

He says that’s the legacy of South Dallas that he wants to make sure people outside the community understands.

“We had all of that, good, bad, and indifferent,” he says. “But through the years and all these systemic policies, this is what’s left of it now. How do we shape and imagine what it looks like over the next 50 years? The park is a catalyst, the project to help those stories get told. The community deserves to have amenities. And for the city and the region, the park deserves to be preserved. So how can we be that vision? How can we show people how to do it right?”

Brown says that all the large projects in the area hew closely to that philosophy, including the Forest Theater plans from Forest Forward, a new Park South YMCA, and the pedestrian-minded improvements along Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard.

He says the plans for Fair Park are designed to make the place a regional destination, but it more importantly needs to be an amenity for its neighbors.

“And it just so happens that this is an area where so many homes were lost, where that generational wealth was robbed,” he says. “So this park is for the community. We can’t go back and correct it, but we can make sure the stories remain part of the legacy and the history of Fair Park.”

Brown says that as Fair Park First began talking to its neighbors, it took pains to make sure that residents in the zip codes immediately around the park were given opportunities to provide feedback. That has paid off in support and engagement, he says.

The increased mobility coming from the connection to the Santa Fe Trail, DART, and the new jobs that will inevitably follow a renewed interest in commercial, retail, and even new hotel construction will also mean that residents might be able live and work closer to home, too, Brown says.

Luallen says his organization is keenly aware of how Fair Park has historically played into shaping the communities around it, for better or (more frequently) worse.

“We’ve never gotten involved in external development because, frankly, the trust isn’t there after taking hundreds of homes largely on behalf of the park back in the 1960s—that left a really deep wound,” he says. “When we were first going out to the community asking if we were the team chosen by the city to run this, what would you like to see us do, it became really clear to me that we weren’t really welcome in those housing discussions. And I understand why—the last time we reached outside our borders, it was not for their benefit. In fact, it left a tragically deep scar that is not ancient history.”

Instead, the organization is focusing on improving the park and its amenities. “We certainly don’t have the naïveté to think that what we do happens in a vacuum,” Luallen says. “We always knew that we would start to see people taking note as we got closer to the delivery of some big projects, and we are certainly seeing it now.

“Throughout that process, my sort of nightly prayer is always, you know, ‘let us do good but let us also do no harm.’”

…But Not the Only Catalyst

Part of Luallen’s fear, he says, is that rising property values will lead to tax increases that price out legacy homeowners.

“It’s much needed investment that helps stimulate further investment from the public sector, and in infrastructure that is sorely needed. We do need more housing solutions, and this is a great part of town,” he says. “But it does create compression that could be really disruptive to some of the historic neighborhoods that surround us.”

Brown said that it’s not just homeowners; renters suffer, too. “A lot of property owners, because of their exemptions, are protected a little bit from the volatility of property tax values,” he says. “But our folks getting hit the hardest are renters because landlords don’t get those protections.”

But Brown says that not all the blame for the increased interest—and the rising property taxes that come with it—can be laid at the feet of Fair Park.

“We’re two miles from downtown Dallas, plus or minus,” he says. “So we can talk about the convention center, we can talk about the Cedars—it’s this perfect storm, in essence, and the lowering of I-30 is only going to connect all that together. Fair Park sometimes gets put in that place where we have to fix everything.”

Both agree that much of the disruption here is coming from private investors that flip single-family homes.

“You have some folks in the market that are calling people in the surrounding neighborhood six, 10, 12 times a day,” Luallen says. “I have a very good friend in Dolphin Heights, and she jokes with me all the time about how many calls she gets a day from people trying to buy her home. I’ve heard local advocates joking, ‘We should all pool our resources and buy billboards that say, ‘Don’t sell your house.’”

Luallen said he hopes that more property tax relief and other policies will help prevent the displacement that plagued the community when progress came calling before.

“We hope to see the excitement married with some good policy decisions that can help create some property tax relief so that we don’t just need to worry about the displacement of the existing population,” he said. “But it would also be really nice if the communities that have made South Dallas and Fair Park their home for many decades could actually reap the benefits of this incoming investment and increased equity. That would be really profound.”

Fair Park sometimes gets put in that place where we have to fix everything.

Jason Brown, resident and community leader

Bazaldua says that he’s always looked at the Fair Park area as a place to “promote smart growth.” But as the city uses the strategies it has at its disposal, he says it will “need more legislation and more tools in our tool belt to help.”

“I’m excited for the direction we’re headed, I just think we need to emphasize how important it is to bring growth that will enhance the quality of life for existing and legacy residents,” he says.

He hopes that, eventually, there will be appetite at the state level to codify alleviating some of the property tax burden from legacy residents around Fair Park. He points to legislation that didn’t make it to the floor during the most recent session that would have allowed cities to use tax increment financing funds to offset the tax bills of legacy homeowners.

“There’s a lot of momentum and great things happening all around Fair Park, and the stars have aligned for us to really prioritize what needs to get done there and for this growth to be for the community,” he says.

He wants to see a balanced approach to development and encouraging property owners to include existing small businesses in their mixed-use plans, especially if they plan to request city incentives.

“I’m not going to bring the city to the table if it’s not going to lift up and bring the existing community as part of what we’re doing,” he says. Those conversations have been a “mixed bag,” but he feels that it’s an important part of that smart and methodical growth. “Maybe it results in nothing sometimes, but it also resulted in not making the same mistakes over and over again.”

Luallen says if things go well, the faces he sees at community meetings will be a mix of legacy residents and new faces.

“In a perfect world, I would get to see those friends and neighbors continue to thrive right alongside new people moving into the area, but we all know we don’t live in a perfect world, and that causes me great concern,” he says.

Brown points to the abundance of longstanding neighborhood and community associations around Fair Park that look out for each other and make sure that residents stay engaged and know what is happening in their area.

“We talk about equitable, but the blight and some of the things that long-term residents have to deal with, that’s not equitable. So how do we arm people with the right tools and resources to contribute and stay in the neighborhoods and enjoy these new amenities?” he asks.

“I want the North Dallas treatment, and to get it I’m going to give you the North Dallas hell,” he says, laughing. “That’s what I’ve been working on for over the last three years.”

Spriggins grew up in the Fair Park area, went to college, and then returned. He says he knows that all of these plans won’t turn back the clock and return property to Black homeowners or erase the ravages of how I-30 disconnected the neighborhood from the rest of the city. But trying to right those wrongs is also important.

“Trying to mend the city back together in a way that it was once before—that’s a challenging notion,” he says. “I think there’s just got to be some thoughtfulness around it, and I also think people need to understand the history of what the city was, so you can try to mitigate some of those mistakes.”

But these changes in infrastructure are foundational. And not just the large-scale project for I-30. Spriggins said that even converting S.M. Wright (technically known as U.S. 175) to a boulevard two miles south of the park is a start, because it is “literally slowing down traffic” to create opportunities for new businesses and new residences. If every change is as intentional and impactful as that is poised to be, there could be some real betterment.

But most of all, he says, he hopes that this momentum is a tide that can’t be stopped. He’s watched smaller efforts start, stutter, and stop since middle school. (For context, he earned his bachelor’s degree in 1997.)

“This is what I call the final frontier,” he says. “With the expansion west to Trinity Groves and all the things that have happened from the Trinity down Singleton, and now we’re seeing what that is starting to look like going south, you kind of felt like this neighborhood was going to be the last neighborhood to get the attention it needed and deserved.”

What Fair Park will look like in 10 years is still unknown. But for the first time, nearly everyone involved feels that the pieces are finally coming together—and that optimism just might be the newest thing for the neighborhood.

Matt Goodman contributed to this story.

Author