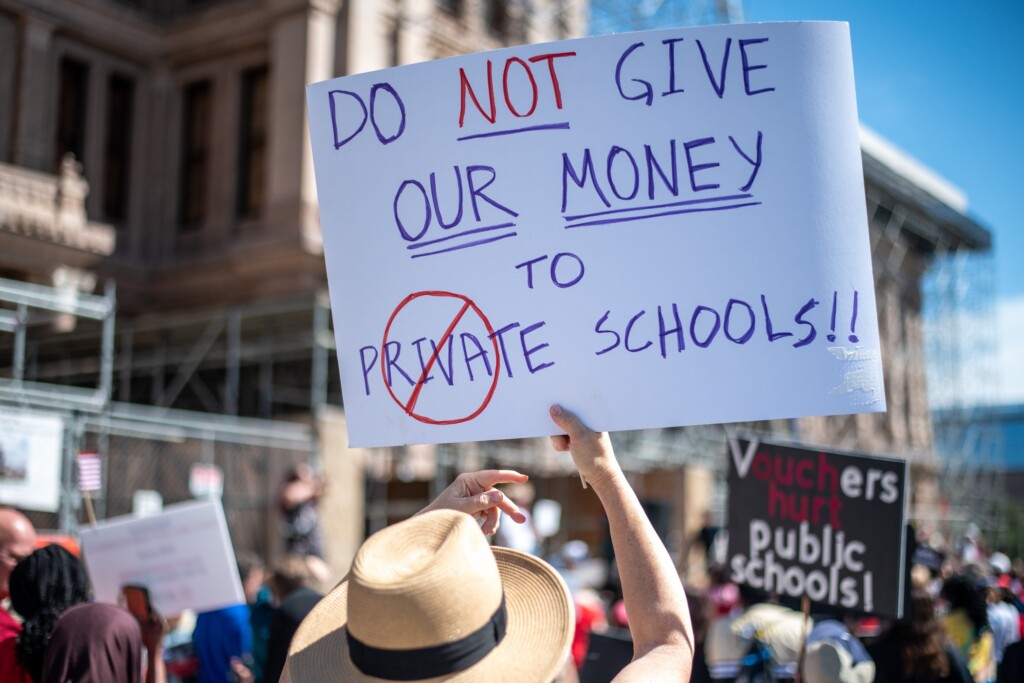

The third special session in Austin has been chugging along for only three days, and already there has been a great deal written about the biggest item on the lawmakers’ to-do list: school vouchers.

Proponents of vouchers or “education savings accounts” say this push is to give parents choices on where they send their kids to school, giving additional resources to families who choose private or home schooling. Opponents say it’s an idea that’s been defeated time and again in Texas, lacks accountability to taxpayers and parents, and has been proven ineffective in improving student outcomes.

There’s a vertiginous amount of discussion on the merits and disadvantages of the so-called school choice movement supported by Gov. Greg Abbott. (We wrote about the discussion just as the regular legislative session began last year.) Nothing passed in that session. Abbott has vowed that some form of voucher legislation will need to come across his desk, or he’ll continue to keep lawmakers in Austin through multiple special sessions.

But on Monday, just as the debate over the governor’s priority matters of school vouchers and education savings accounts began, state Sen. Nathan Johnson (D-Dallas) posed a question to a roomful of reporters: “How many of our so-called failing public schools are in affluent neighborhoods?”

He was asking who vouchers are intended to help and whether they are actually intending to address the social and economic issues that often impact the trajectory of public schools. According to last year’s accountability ratings, more than 90 percent of the state’s public school districts earned at least a C, with 75 percent earning a B or above. Dallas ISD earned an 86.

To Johnson’s point, many of the same schools that are often labeled “failing” are dealing with issues that you don’t typically see in more affluent schools. Jack Schneider, an education historian at the University of Massachusetts, pointed to a study this week that explored how accountability is often based on the assumption that schools are failing for lack of effort—a view that is often also repeated when people talk about the need for vouchers. The authors, Marshall Smith and Jennifer O’Day, warned in 1993 that it is often erroneously assumed that schools are low performing because “school personnel lack the will to improve.”

The two say that when teachers and staff are not supported, don’t have the resources, or where staffing a school fully is a problem, “as it is in many schools serving poor and minority students,” sanctions and rewards alone won’t work.

In a conversation with D Magazine, Johnson pushed back against the idea that vouchers were the answer to improving education outcomes.

“Pretending that a voucher is going to solve the problem by pretending these failing schools are the problem means we’re really missing the real point—we have some broken and underdeveloped social systems are creating conditions where it’s difficult to learn,” he said. “I also think that if you’re going to fix schools, fix schools. Its remarkably unimaginative—and I’ll use this word again—and it’s lazy to just say, ‘Hey, I know how we can fix it, let’s just do nothing and cut checks.’”

To further illustrate how outcomes are impacted by investment in schools, the New York Times’ Sarah Mervosh published a story this week about a school system that has found immense success in teaching students. If the system she studied was actually a school district, education wonks would be attracted in droves to see if its methods could scale.

Those public schools are run by the U.S. Department of Defense, and located on military bases worldwide. And while they do have their own set of challenges, as all school systems do, the story identifies a formula of sorts: it becomes much easier for kids to learn when teachers are paid well, they have at least one parent employed full-time, their housing is stable, and they have access to healthcare their family can afford.

“Having as many of those basic needs met does help set the scene for learning to occur,” one principal told Mervosh.

Dallas ISD estimates that about 85 percent of its students are economically disadvantaged. Statewide, about 60 percent of all students fall into that category.

But it’s not just economically disadvantaged students who won’t benefit from vouchers, researchers contend. Michigan State professor Josh Cowan, who has studied voucher programs for 20 years, says it’s most likely that the private schools that will take a voucher will be faith-based. Evidence shows that those schools will be allowed to refuse anyone.

“LGBTQ parents, divorced parents, single mothers, students with disabilities—those are the ways we know other voucher programs have discriminated,” he said. “For the first groups, they can claim a religious exemption, essentially, and for the second group, they can claim the inability to provide the service.”

The Senate is currently considering two bills. One addresses the basic allotment for per-pupil funding and another introduces what’s known as education savings account, or an ESA. Unlike a health savings account, where an individual contributes a portion of his or her pre-tax paycheck toward the account, an ESA would be wholly funded by the state.

The former bill offers a one-time raise in teacher pay and a $75 increase in the basic allotment of $6,160 per student. The basic allotment is the baseline funding each school district or charter school gets from the state for each student who attends.

When a student falls into additional populations—bilingual, special education, gifted and talented, or a student on the Career and Technology track—additional funds can be apportioned from other sources. It’s a relatively arbitrary number, education advocates say, that isn’t tied to inflation. The last time the basic allotment was increased was in 2019. Inflation has increased by about 17 percent since that time, while the per-student spend has stayed static.

The savings account bill would offer parents $8,000 to be used toward tuition or education-related expenses like uniforms, books, or supplies at a private school or in a home school setting. (A fiscal note for the bill does acknowledge that this could decrease the dollars for public schools.) It sets aside $500 million for the program; if there are more than 62,500 applicants, there would be a lottery for the funding.

If it went to a lottery, 90 percent of the funds would be for students in what the state deems to be low-rated schools, who are economically disadvantaged, or have a learning difference. There are roughly 5.5 million public education students statewide and 1 million in private school or home school.

Even if there was enough funding for all those students to have a voucher, a map created by the Dallas Morning News illustrates the inequitable distribution of those campuses statewide. In some parts of the state, there are no private schools for hundreds of miles.

In other states where vouchers or ESAs have been implemented, Cowan says the results are stark. There is no requirement that private schools face the same accountability measures that public schools do. So voucher programs often produced students that either scored roughly the same as their public school counterparts, or worse.

Analysis from the Brookings Institution and Chalkbeat found much of the same thing. The research also found that in nearly all programs, the most frequent voucher users were students who were already attending private school, not former public school students.

It has also not been kind to state coffers. In Arizona, Gov. Katie Hobbs announced Tuesday that its voucher program was fiscally “unsustainable” and that it “does not save taxpayers money, and it does not provide a better education for Arizona students.”

Both Cowan and Johnson share twin concerns: the relatively small voucher provided to each student, combined with a lack of accountability, will ultimately result in a proliferation of failing private schools.

“Which parent is willing to be the last parent to enroll their child in the school that’s about to close?” Cowan asks. “Which parents are willing to be the parent whose kid is the last kid to get a low score on the ACT before that school closes, and they waited six years to find out that they’re even further behind?”

The second concern is that this legislative session’s voucher bill will pave the way for a larger bill that will siphon more funds from public schools in the long run, just as it has in other states that have adopted such programs, like Arizona.

Johnson also questions the rhetoric around parents being able to fund students, not systems, with their tax money. About 75 percent of Texans, he says, don’t have a child in the public school system, but are paying property taxes.

“This notion that every kid, every family gets to have a voucher because that’s their tax dollars is nonsense,” he says. “That’s everybody’s tax dollars. If somebody wants to go to a private school, they can do with their own money.”

With the promise of unlimited special sessions looming, Johnson said all Texans should be worried about the prospect of vouchers, even with vocal, nearly unanimous opposition to them from the business community, voters, many faith leaders, and education experts.

“I mean, look, I try to be objective—I try to think from the perspective of somebody who is in an area that that’s his school is not meeting the kid’s interests or whatever, and you want to believe that a voucher is your deliverance, right?” he says. “That’s the really the sinister nature of this whole thing—we’re preying on people’s hopes. They see a voucher as their ticket out of poverty or their ticket out of a difficult neighborhood, and it’s a false promise. We have false promises everywhere.”

Author