Samuel Adler only lived in Dallas for 14 years, from 1953 through 1966, but his legacy in our music history is outsized. He led the predecessor to the current Dallas Opera; he taught music at the University of North Texas and the Hockaday School; he composed numerous works for the Dallas Symphony and served as its cover conductor (a stand-in or understudy); he helped organize a chamber music society that still operates today; and even now remains the composer who’s written the most classical music for local orchestras and ensembles.

And all that stuff wasn’t even his day job. He came to Dallas as music director for Temple Emanu-El, where he led choirs and held concerts at both the old South Boulevard location and the now-well-loved campus on Hillcrest Road. As Adler says today, “A young man has to keep busy.”

For good reason, Adler played a major role in our feature last year about the history of new classical music written by and for Dallasites. But he’s not done just yet. The composer turned 96 last Monday, and he’s still working on new music, including a piece he hopes will be performed by the Dallas Symphony in spring 2025. If it is, it’ll be the ninth work he has written for the DSO. (The most recent, Lux Perpetua, premiered in 1999.)

These days, Adler admits he is finally starting to slow down—but he’s still creating new work, including an award-winning album of sacred music. He recently gave a fascinating, free online lecture that details his upbringing as a German Jew and his family’s narrow escape from Nazism. There’s a chase-scene escape from German troops, involving the young Adler sneezing at the exact wrong time, that could be in a movie.

Shortly before his 96th birthday, Adler took an hour-long Zoom call to talk about his career in Dallas, the city’s music history, lively parties at the Marcus house, and why everyone, especially retired people, should find ways to develop their creativity.

Tell us how you came to Dallas.

I went to Dallas right after the Army. I got out of the Army in December 1952, and my father was the cantor at Temple Emanuel in Worcester, Massachusetts. Rabbi [Levi] Olan, who was the senior rabbi at Temple Emanu-El in Dallas, used to be the rabbi in Worcester. They were very close friends.

In the Army, I had founded the Seventh Army Symphony Orchestra. And when I returned to the U.S. from Europe, I had a job offer because Leonard Bernstein was leaving Brandeis University. I had known him as a student in 1948. However, my parents, unknown to me, had negotiated with Rabbi Olan. I walked into the door, the phone rang, and it was Rabbi Olan. He said, ‘No, you don’t have a job. But I’m going to send you a ticket to fly to Dallas and talk to the music committee.’

I had been in Dallas because I was stationed at Fort Hood. [Emanu-El] had not built the new temple yet. It was down on the south side. Two years after I got there, we were in the new building on Northwest Highway.

Two days [after the job interview], Rabbi Olan called and offered me the job. He said, ‘I know you wanted to teach at a college, so we worked it out with SMU that you can teach.’ Wow! I had it made!

I bought a car with my severance pay from the Army. I got there, got myself an apartment, and the first thing was the job at SMU fell through. They didn’t have the money and so on. They did give me an honorary degree, so that’s all right. (laughs)

He says, ‘Sam, I want you to take over the opera.’ I say, ‘What? I just got here.’

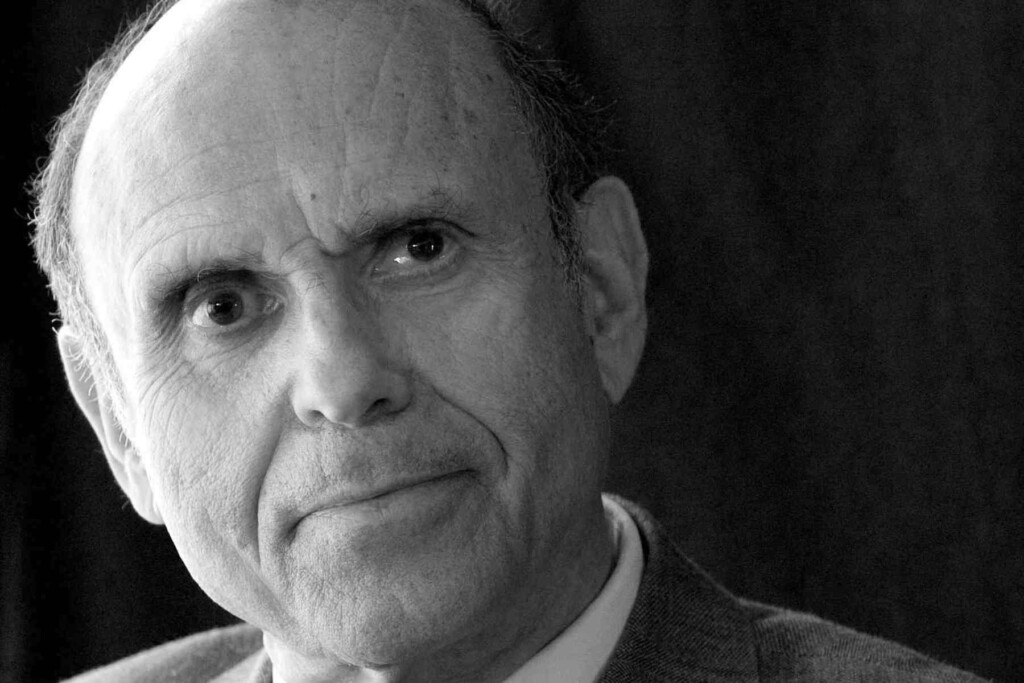

Samuel Adler

Things happened so fast, it was incredible. The second week I was there, I read in the Dallas Morning News that the University of Texas and the Dallas Symphony were running a commission for a work to be performed the next season. I had nothing to lose, so I put in my dissertation and my master’s thesis. I started the job at Temple Emanu-El. And the conductor at the opera, it was called the Lyric Theater, wanted to retire. There was a man, music critic of the Morning News, John Rosenfield—he was the czar of music and art. Unbelievable. If he wanted something, it happened. So I get a call from John Rosenfield. He says, ‘Sam, I want you to take over the opera.’ I say, ‘What? I just got here.’

So I had an opera job right away. My first and second operas were produced in Dallas. The first one, The Outcast of Poker Flat, which had quite a few performances, and then the American Guild of Organists, when they had their convention in Dallas, commissioned in an opera to be staged in church, called The Wrestler.

The next thing was, John Rosenfield also called and said, ‘Suggest something to me. Let’s do something in a private school. I think at the girls’ school, which is the Hockaday School, we’d like to have a course taught by a composer, an artist, and a poet.’ I went to teach that.

It was a wonderful course and I taught it until the year before I left Dallas, which was 1966. I’ve always liked Dallas. I always like to come back, but I’m about to turn 96, so it’s not too easy to travel anymore. But so far so good, let’s put it that way.

The class at Hockaday, it was just generally the arts and creativity?

That’s right. I taught twice a week, the artist taught twice a week, and the poet twice a week. It was oversubscribed always. Girls really liked it. They composed some, they wrote poetry, they painted. It was really active.

You wrote three symphonies for the Dallas Symphony. How did that happen?

Right after my birthday in March, they announced that I had won the Dallas Symphony prize. I called the conductor, Walter Hendl. He said, ‘I want a big piece. Not just this.’ So I thought, well, I’ve always wanted to write a symphony, this is my chance. I wrote the First Symphony that summer and it was [played] in December, I think December 10, 1953. John Rosenfield liked it!

The Monday after the performance, I get a letter from McAllen, Texas. I don’t know anybody there. It’s Mrs. Goldstein. She writes, ‘I went through Dallas on Sunday and saw the review of your Symphony, and I was wondering if you’re related to my old friend Hugo Adler.’ My father! Well, we found out that Mrs. Goldstein was his girlfriend when he was a young teacher. So I always called her daughter in McAllen my sister.

I was single, and the thing that happened when you’re single in Dallas, especially with a congregation in back of you—everybody has a daughter! I never had a meal at home!

Walter Hendl loved the symphony. He said, ‘Keep writing for us.’ The next thing I wrote was Toccata for Orchestra, which premiered in Dallas and then in Chicago. I’ll never forget, I went to Chicago to hear it. It was a great performance, and afterwards a friend of mine came up to me and said, ‘You know, Sam, I felt that there was a whole herd of elephants chasing me all the way, beginning to end.’ Well, I think that’s better than saying, ‘It was interesting.’ You felt something!

My father died, and I wrote my Second Symphony, which is dedicated to the memory of my father. After that came one piece after another. There are eight pieces that the Dallas Symphony commissioned. My Fourth Symphony also.

It’s my wish that every city, every town, would have places where people could go to play, to read, to paint, to write poetry. Every library should be open all the time for these things.

Samuel Adler

With your first two symphonies for Dallas—the backstory makes sense because the Second felt more emotional, more lived experience. The first one is more optimistic.

I was influenced very much by Aaron Copland, who was my last teacher. We always had a great relationship. And by the way, Copland was related to the Marcuses from Neiman Marcus. Mrs. Marcus was a first cousin of Aaron Copland. When he came to Dallas, we had the most fantastic party at her house. It was something else. He had many relatives here. The Mittenthals were related to his mother. Minnie Marcus—she threw a party like nothing else. My years in Dallas were just wonderful. I had the best time.

And then in 1966 I was asked to join the faculty at the Eastman School. When I left, they—the Dallas Symphony, the temple, the Chamber Music Society, and North Texas—commissioned a cantata called The Binding which I conducted the first performance of just before going to Rochester. Before that, I was also co-chair to the Dallas Chamber Music Society with Dorothea Kelley. Do you know who she was?

No.

Dorothea Kelley was the principal violist of the orchestra. She died at [age] 104. [After Adler left town, she continued to run the Dallas Chamber Music Society for more than 50 years.] Her husband worked for Bell Helicopters. He was such a music lover that he took music lessons from the oboist of the Boston Symphony, and he flew the helicopter up there once a month to take a lesson.

But let’s get back to the Temple. At the Temple, I was able to start the children’s choir and—I called it “from womb to tomb.” We started with the third graders and people graduated into the adult choir. We did terrific music. Any time a new piece was written for the reform Jewish service, we did it. We were known for it. We did the Ernest Bloch Sacred Service and he wrote me a note saying it was the best performance he’s ever heard. We did the Darius Milhaud Sacred Service and he came to the performance with his wife. The Dallas Symphony did a piece of his and it worked out so that it would be at the same time. We had a wonderful weekend together.

Yes—the DSO played Milhaud’s Eleventh Symphony. To be honest, I listened to it and I didn’t like it.

Let me put it this way. Milhaud wrote too much music. He wrote a piece every day. Some were very good and some were, mmm, not so good. I just had the premiere of my Seventh Symphony. But that’s my last symphony.

You’re not going for nine?

Nine! No.

What was Dallas like artistically when you were here? I understand the city was very ambitious to make its mark.

When I was at UNT, we made an agreement with the Dallas Symphony that any time they had a guest, we would have the guest at North Texas and pay for it. [The DSO] came up once a year to play student works. The Dallas chamber music series, quartets went up to North Texas to play. I wrote three quartets for that series.

Walter Hendl was let go, and I was cover conductor for the Symphony. That means every week they had somebody new come in—Leopold Stokowski, Eugene Ormandy, Sir Thomas Beecham, Ernest Ansermet. It was a fantastic year. I had to be at every rehearsal, and they rehearsed at the Temple, by the way. I felt it was a new education for me. To see these people in person! Ormandy was the only one that asked, ‘Do you have a piece I could look at?’ I had written Requiescat in Pace. It was written in three days after the assassination of JFK.

Another time, Lynn Harrell’s mother, Marjorie Fulton, was killed in an automobile accident. [Fulton was a violinist and UNT professor; Harrell, who was left orphaned, became a world-renowned cellist. The Dallas Symphony now holds an annual Lynn Harrell Concerto Competition for young performers from Texas and neighboring states.] On Tuesday, [DSO conductor] Donald Johanos called me and said, ‘Sam, Marjorie was killed, could you write a piece for Thursday’s concert?’ So I wrote it, he did it on Thursday, and it is now my most performed piece. It’s been done by New York, Los Angeles, San Francisco, the Berlin Philharmonic. It’s called Elegy. [The Berlin performance was at a special concert commemorating the 70th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz, played on violins owned by European Jews during World War II.]

But there was something always about composing that I needed to do. I wanted to hear something I did myself.

Samuel Adler

You know, I can’t complain about things. I’m still being commissioned. One of my CDs just won first prize—the Bacon Prize, and it’s given by some organization for the best recording of sacred music. It’s called To Speak to Our Time. It’s on Spotify and all those. They won first prize. It’s the best chorus, I think, in America today, called Gloria Dei Cantores.

You have such wonderful church choirs still in Dallas! It’s a source of great joy to have them do quite a few of my things.

That’s interesting, church music by a Jewish composer.

I even wrote a mass for Notre Dame [University]! When they had their 100th anniversary, Father Hesburgh called me. He said, ‘Sam, I’d like you to write an ecumenical mass for us.’ I said, ‘Don’t you think you have the wrong number?’ (laughs) He said, ‘I know who I’m calling.’ It’s called We Believe. It’s using the Catholic text and putting other religions in it. I have two masses that have texts from other religions.

Researching the history of the Dallas Symphony, I learned that there has been a lot of change in the economics of how a composer makes his living. That back then, a composer taught for a living and got peanuts from the orchestra for playing his piece.

Nothing! Yeah. The important thing was to have a publisher who could collect the royalties. For instance, if a symphony of mine is done, they’re all published, so the publisher gets a rental fee and I get 50 percent of that. Much better now.

A young composer starting now, it’s difficult because of another thing, and that is, there are so many! And very good ones. Some of my students—Kevin Puts has a piece performed for a second season at the Metropolitan Opera. Mason Bates. I could name you 10 or 15 composers that have made it really big. I love it. And they’re so loyal. I have the best time because they’re all in touch. This is the thing you get from that many—I have 68 years of teaching. Those are the benefits. I’m just so happy with my students.

What speaks well of you as a teacher is they are stylistically so different.

Absolutely! And I insisted on that. Walter Piston was one of my teachers. Absolutely fantastic composer. He was very impersonal. We never had private lessons. But when I graduated, I was already drafted, and he had to hand my dissertation back. So he said, ‘Why don’t you come to my office?’ I went there and he said, ‘You know, Sam, I worry that my music will not be known or played in 25 years. That it will only be known that I’ve written an orchestration book, a harmony book, and a counterpoint book.’ I said, ‘You’re the most famous composer in America!’ He says, ‘Yes. Now. But maybe in 25 years, you know?’

And I worry about that too. I have written an orchestration book that has sold over a million copies. It’s translated in 10 languages. I sometimes wonder and hope that it isn’t the only thing I’m remembered for.

I am enjoying life because I can still create. I want that for everybody.

Samuel Adler

I was listening to your online lecture, 95 Years of Music to Speak to Our Time. You talk about beginning as a violinist but getting an itch to compose, or a little envy of the composers. What was—in a little more detail—what was your spark for composing?

My father was a composer mostly of Jewish sacred music, and a very good composer. He was a student of Ernst Toch, who was our neighbor in Mannheim. My father was his copyist because he couldn’t afford to take lessons and pay for them. I watched my father, I watched the success of some of his pieces. He did not teach me. He said, ‘A father shouldn’t teach his son.’ So he sent me to Boston every week to study with Herbert Fromm, who was a wonderful composer and was Hindemith’s favorite student. But there was something always about composing that I needed to do. It wasn’t enough to play the violin or the piano. I wanted to hear something I did myself.

How often do you go back and listen to everything you wrote before?

Not very often. Only when people come and say, ‘I want to play your First Symphony,’ or something. My latest project was to orchestrate an organ piece by Marcel Dupré, called Variations on the French Noel. Wonderful piece. I’m happy to say that the conductor who conducts the Dallas Symphony pops concerts, Jeff Tyzik, I hope will do it with the DSO next season. He is a great talent. Send this article to him. That’ll do it!

One last question, about the course at Hockaday with girls composing, painting, writing poetry. I wondered if you had a little lesson for readers about creativity, the muse, anything you taught back then.

I feel that people have creativity within them that they don’t know. Especially when you retire. Look, if you retire at 65, I’m now 96 almost. You don’t know how long you’re going to live! The best way of filling the time is with creativity. Doing something for other people. The most wonderful thing about our house here is I have a library, a place where I have hundreds of books. To read for a couple of hours every day is the greatest gift you can have on retirement. I try to read as much about things I don’t know as possible. Because I don’t know a lot of things!

The time after retirement is the time to really get everything you can out of life. If you’re well, and up to now, I’ve been OK. Everybody has some creativity in them. When I was at Eastman, we started two senior bands. Everybody was 60 or above. We always had a hundred people in each band, and they were pretty good! They rehearsed every single day. Why not? Now they have started that in Europe. In Mannheim, they have a city wind ensemble. When the city celebrated its 400th birthday, they commissioned me to write for the wind ensemble. It’s made up of a lot of retired people who are terrific.

It’s my wish that every city, every town, would have places where people could go to play, to read, to paint, to write poetry. Every library should be open all the time for these things. I am enjoying life because I can still create. I want that for everybody.

Update, Mar. 12: This article has been updated to correct the names of Ernest Bloch, not Ernst Toch, and Father Theodore Hesburgh of Notre Dame.

Author