As I prepared my list of exhibitions to see before the year’s end, I realized something quite striking: of the eight shows I highlighted, only one—the extraordinary exhibition of Bonnard at the Kimbell—focused solely on a dead White man. Of the others: if they are dead, they are not White. If they are White, they are not male. They are female or otherwise outside the canon; they are BIPOC and queer.

Last year, the International Council of Museums redefined their definition of “museum” to include the words “inclusive” and “foster diversity.” It was the first revision of the term in 15 years, according to a recent New York Times article. The Mellon and Ford Foundations, among others, have been investigating art institutions, placing pressure on them to adopt approaches that rhyme with the times. (And a Leadership in Art Museums initiative, comprised of several of those foundations, has allocated $11 million to increasing racial equity in museum leadership.)

And while many see more work to be done, if DFW’s current temporary exhibition roster shows anything at all, it’s that we’re utterly in line with a growing movement, reflective of a profound shift that’s being felt throughout the museum world.

The first thing to understand, in assessing how and why we got here, is who our curators are.

María Elena Ortiz moved a year ago from her position at the Pérez Art Museum in Miami to become the curator for the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth. Focusing on local artists, she curated a solo show by Dallas-based Jammie Holmes. (It would have been in my line-up for its importance had it not ended in late November; read the review here.)

“I think audiences are shifting. If museums want to engage with those audiences, they have to have artists and stories that resonate with those communities,” Ortiz says.

Ortiz’s colleague, curator Alison Hearst, who was charged with bringing the exhibition Jaune Quick-to-See Smith: Memory Map, organized by the Whitney Museum of American Art, to the Modern (for which the schedule and the entire second floor were cleared), agrees that this is particularly important for any institution showing modern and contemporary art.

She describes this local and national moment as “exciting and energizing,” a “zeitgeist” she has longed to see since she began organizing exhibitions in 2014. “Museums are striving toward reflect[ing] the communities they serve,” she says. And Fort Worth “is such a diverse community.”

For Emily Edwards, the curator at the Dallas Contemporary, to be tapped into the moment is fundamental.

“My interests have always been in artists who are creating work that’s responding to the sociopolitical topics of our time. Often the people who take on that mantle are people of color or women. Or they’re non-conforming people or queer people.

“I do believe in the soft power of art: it draws in anyone because it’s beautiful, but when you look more into it, there’s something more substantial there,” she says. “And I believe if you pull people in with the beauty, they can often learn something or change their mind or soften some of their belief system.”

Bianca Bondi, the multimedia installation artist currently on view, is one in a cast of all-female artists Edwards has brought in since she took over the curatorship from Peter Doroshenko.

She is acutely aware of the curator’s identity relative to that of the artist. Intentionally or not, she has espoused a certain one-to-one model as a female curator who has organized shows of female artists. But when is such an equivalency important? Are there times when it’s more vital that the work be shown?

“It’s something I think about a lot,” Edwards says. “I am White, cis, heterosexual. I’m not really in a marginalized community at all. But that does not ever stop me from curating shows with people of color or queer people or non-binary individuals. Because I view my job as giving a platform to those who often don’t get one.”

But given that the artist-curator relationship is based on trust, “I would never be offended if an artist preferred to work with someone they feel safer with,” Edwards says.

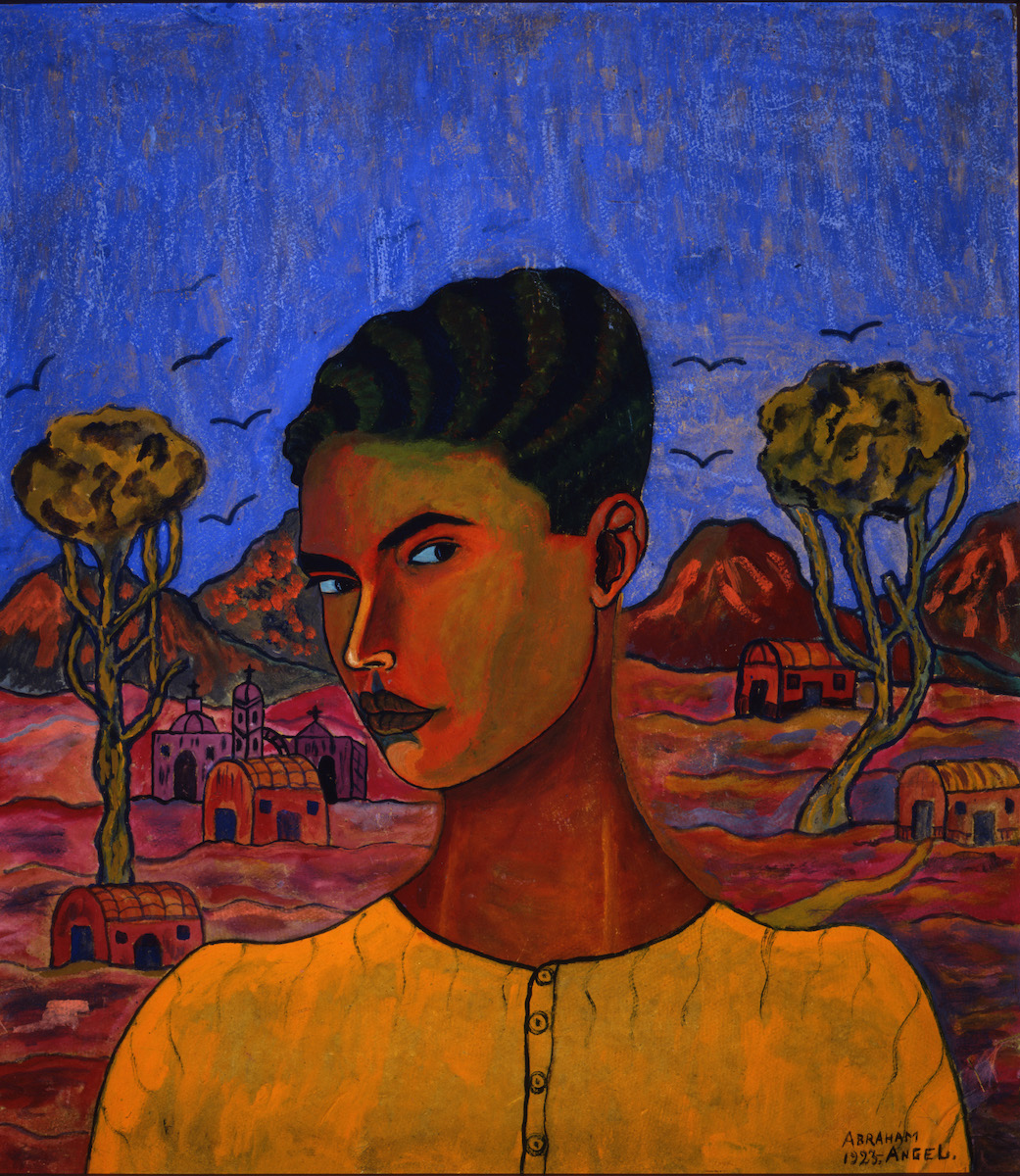

At the Dallas Museum of Art, Mark Castro curated the exhibition Abraham Ángel: Between Wonder and Seduction, based on the 20 extant works by a young, queer Mexican artist who contributed to Mexican modernism. The exhibit was spurred by an intellectual passion. Elsewhere in the museum, Assistant Curator Ade Omotosho shepherded the touring exhibition Afro-Atlantic Histories on the history and imprint of the transatlantic commerce in enslaved people.

At the Nasher, curator Leigh Arnold is explicitly correcting the historical record by putting forward the work of 12 female artists of the Land Art movement.

These are among our curators, and I would argue strenuously that, boards and finances notwithstanding, what matters to them shapes what we see. But we should also be looking at the permanent collections in each museum and focusing on what the institution’s curatorial team is doing and can do behind the scenes.

The Dallas Contemporary is a non-collecting institution and operates from a blank slate. The others acquire works that fill the galleries; what’s on display depends on what’s in the vault. If they know what they’re doing, they’ve been pushed to look critically at themselves and at their collections.

The Modern’s chief curator, Andrea Karnes, who curated the blockbuster Women Painting Women last year, describes a formal assessment in 2019 that took stock of both exhibitions and collection holdings.

“We were sort of shocked to find that we hadn’t done as many exhibitions with women artists or with Black or Brown artists as we thought we had. It was like, ‘We thought we were doing better than this,’” she says. As for the permanent collection, “it didn’t look the way we wanted it to.” That is, it resembled any other modern and contemporary art museum in the country: “It looked like mostly White men, frankly,” Karnes says. The total hovered around 90 percent.

This raises the question of what we want from our institutions. If 90 percent or more of the collection is White male artists, “what does that say?” Ortiz asks. “It cannot be that only White males are great artists.”

That leads to a museum, she says, that “only has one story. If we’re truly a modern and contemporary museum, we then have to show a more comprehensive history.”

Joining the inaugural cohort of the Truth, Racial Healing, and Transformation chapter in Fort Worth, Karnes, Hearst, and Ortiz chose as their final project a proposal for “course-correcting” the permanent collection.

“That was extremely eye-opening,” Karnes says. They could obviously not guarantee that their proposal would be adopted. But since that time, they have made a concerted effort to present underrepresented work at acquisition meetings. They have been working for breadth, Hearst says, rather than the long-espoused practice of collecting certain artists in depth.

“We know that equity can’t come immediately—that takes a long time,” Karnes says. “But [we’re] just striving toward equity.”

Which should not mean acquiring only small works or works on paper, as has been the reproach about museum collecting when it comes to work by women and underrepresented artists.

That would be too easy. They could readily up the percentage of such artists if they “went out and bought a bunch of” photographs or prints. But they want “heavy hitters in conversation,” Hearst says, which means large works and works on canvas. The goal is to engender dialogue.

“We haven’t put away all the great works in the collection to go collect dust in the vault. Those works are still valid and important, and we still have them out. We’re just adding to them,” Karnes says.

“There’s a lot of work that the museum needs to do, of course,” Hearst says. “We feel we’re at the beginning.” But they share priorities in acquisitions as they bring the museum forward with a new momentum that matches the times. “We’re really at a great moment where we can change these things, but change is hard and slow.”

One conclusion is that the movement toward diversity is not going away. Another is that people crave it.

The curators with whom I spoke would like to see more work by Filipino, Indigenous, and Black-Latinx artists in exhibitions and in the permanent collections. They would like to see more BIPOC visitors coming through their doors and seeing their communities represented.

Museums, Hearst says, “have told one story. It’s time [to make] room for other stories. I think it’s essential in understanding the world.”

The Modern, which has been collecting since 1892, holds only one work by an Indigenous artist in its permanent collection, Hearst says. It’s a piece by Edgar Heap of Birds, a work with a local contextual connection acquired in 1996, and it’s currently on view in tandem with the Jaune Quick-to-See Smith retrospective. And yes, it’s a work on paper. And yes, they know. They’re trying to change all that.

Author