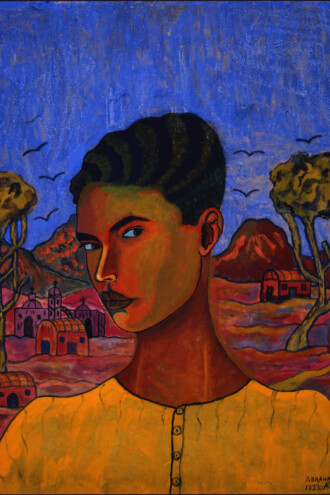

The self-portrait shows the face of a full-lipped teen who is turned three-quarters toward the viewer. One arched eyebrow is cocked above an eye that glances sideways, sly and confident at once. Mountains and a typical Mexican town, rendered in brilliant colors, dot the background. Its skill hints at the work of an older artist than who is responsible for it.

The Dallas Museum of Art’s Abraham Ángel: Between Wonder and Seduction opens with the vision of a painter you should know, but likely don’t.

The exhibit is courtesy curator Mark Castro, whose interest in Ángel began seven years ago while he was working on Mexican modern art at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Castro was arranging a show about a group of artists; the teen in the painting was among them. The period Castro began investigating fell after Angél’s death in 1924. Through his research, Castro encountered Ángel’s self-portrait for the first time in Mexico City and felt an instant connection with the work.

He learned this artist only painted 24 pieces from the ages of 16 to 19, four of which are lost. Castro suspected the work could have ripple effects that were felt down the century. That this teen, who dropped his surnames in favor of his two first names, had become so entwined with the history of Mexican modern art that a century later it is hard to imagine an exhibition without one of his 20 extant oeuvres or an art history volume that doesn’t lionize him. His pieces are being shown at the DMA through January.

“Despite this brief amount of time, despite the fact that he only had a small number of objects with his name on them,” Castro says, he should be seen as as important as Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco, or Frida Kahlo. “How did he become part of this vital story? That hooked me.”

And from there unspooled the life details of this extraordinarily talented queer, biracial artist. (His father was Welsh.) He was romantically and professionally involved with fellow painter Manuel Rodríguez Lozano, nine years his senior. Angél’s sudden death of an overdose gutted the artistic circles of Mexico City. His works speak to larger questions that were at play in Mexico and the Mexican art scene in the 1920s, particularly around people and changes he was seeing in Mexican culture and society.

But they also “exude this sense of youth and bohemia and the idea of being young and maybe being different, and finding community in that difference,” Castro says.

That context matters. In the 1920s, after the tumultuous decade of the Mexican Revolution, artists and residents at all levels of society were asking questions about Mexican national identity.

After the violence of the revolution, “this is a moment when everyone was saying, ‘we’re going to break with the things of the past,’ the ways of making art, the academy,” Castro says.

A small parenthesis about cardboard: I feel a pang anytime I see that an entire body of work is on cardboard. Cardboard is a nightmare from a conservationist perspective, given how tenuous the hold is on oil paint’s reaction to it. It renders his works, compared to oil on canvas, somewhat more ephemeral. Some art historians have referred to Ángel and a number of his contemporaries as the School of Cardboard, as they were all using this new material. And so Ángel likely turned to the surface because it was cheap and readily available—but perhaps, more importantly, because it was modern.

The works have had the good fortune to be well-preserved, largely because upon Ángel’s death, most were in possession of his partner Lozano. He sold them to a collector in Mexico City, who in turn kept them together in his home. Upon the collector’s death, his son sold them to the Mexican government, ensuring that they’ve been cared for at national museum standards for most of their existence.

But the very medium is a testament to Ángel’s modernity.

So are the portraits. Their gazes intense, his subjects portray a slice of Mexican society in gem-like colors that crackle with vitality. See fellow artist Hugo Tilghman, in the guise of a tennis player, the notoriously brawny physique playfully rendered. See the waitress, her blue-collar social class different from those represented in murals by Rivera or Orozco of working-class men. Ángel portrays them like a gossip would, or an anthropologist.

Depicting those close to him, he was fully part of the culture war happening and the struggle to define the question, Who are we, and who are we going to be?

Which is why, when he died at 19, the artist community was left shaken. Mexico City’s art scene was large, but intimate. It was the sort of cadre, as in cities like Paris or New York around the same era, where artists and poets shared drinks and endless debates and knew one another as intimates. Quickly after Ángel’s death, Lozano produced a book that included eulogies written by artists such as Rivera and Carlos Merida. It included writings by poets within the circle, including queer poets who were part of the emerging community.

The testimonials, Castro notes, are quite raw. Searching, post-Revolution, for a new identity and art form, “They see so much hope in him,” Castro says. “He’s untainted by the past. He didn’t go to the academy and study plaster models. He just started to learn from Mexican artists in a very specific way. As they’re seeing this new talent that’s pointing the way to the future, he’s snatched away.”

In personal ways, he is hinting at the emerging young, queer subculture. And yet Castro sees none of his youth in the paintings. “I see it in his face, of course. But there’s none of the hesitation or lack of clarity of who he is,” he says. None of the lack of confidence or skill that might characterize an artist of 18, as Ángel is when he paints his self-portrait, full of that self-assurance, with his Mona Lisa smile. “He’s an incredible painter,” Castro says, and in that poised, painterly moment, he challenges the viewer.

This unique perspective spools over the ensemble of his works. And to see them all in a room together is galvanizing, 35 years after the last survey of his work.

Some art historians have dwelled on the circumstances of Ángel’s death, which, in his death certificate, is noted simply as heart failure due to ingestion of a toxin (rumored to be cocaine). The declaration has left the door open for a tragic vision of carelessness, depression, or love-lorn suicide. That, however vital to an understanding of his person, can obscure the celebration of his work. “He died, and that it was a tragedy is clear. That his work went on to matter and matters today is [also] very clear,” Castro says.

It is also fitting that a place like the DMA would be the gathering point for these paintings that shine yet another light on Mexican culture. The show is rigorously, thoughtfully about the work—and about Ángel as a trailblazer.

An artist who was great after only 24 paintings.

Author