Last summer, as the mercury rose and the ground soured and cleaved, Barry Mandel had a choice: grass, trees, or flowers.

The hottest summer on record was devouring Houston’s Discovery Green park, torching its 12 acres, as it was most parks across Texas. So Mandel, the park’s president and park director, had a choice: save the grass, save the trees, or save the flowers. City watering restrictions wouldn’t allow the water for all three.

The grass could grow back, he thought, so he watered the trees and flowers and gardens, letting the grasses sear.

Twelve months later, the grasses haven’t grown back, and Mandel’s “green oasis in the middle of downtown Houston” has been forced to launch a Grow The Green campaign, looking for money to fund something that nature’s removed.

“Last summer was devastating,” he says.

These issues—heat, water restrictions, downtown location—mirror the maintenance challenges Klyde Warren Park will face. Throw in its hovering location, its shipped-in soil, and its capped soil depth, and the park’s issues perhaps double Discovery Green’s.

Early on, noted landscape architect Jim Burnett was tapped to draw up plans for the park. The founder of Office of James Burnett, which was launched in Houston in 1989 and opened a San Diego office in 2003, was charged with creating a plan for something that didn’t exist—like being asked to paint something without a canvas.

Burnett also put Nathan Elliott, a vice president in his California office, on the project. Elliott had lived in Dallas from 2005 to 2008.

“When we were making some initial site visits, we were literally the only people out there,” Elliott says. “There were maybe a couple stragglers, but by and large it was just kind of no-man’s land; the opportunity to make ground out there was pretty captivating.”

Belo Garden and Main Street Garden hadn’t sprouted when park planning began in 2004, so there were no other Dallas models to draw from.

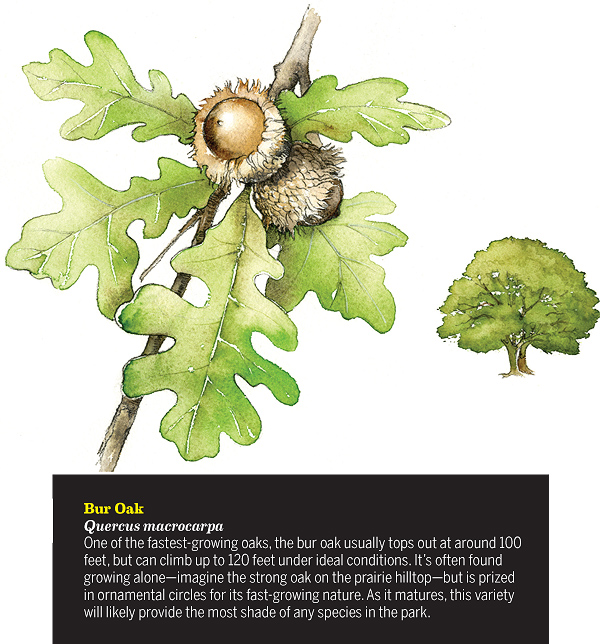

Elliott and Burnett got to work. One unusual issue to contend with: weight. Built on a deck that hovers above thousands of passing cars, every pound needed to be accounted for. If a Shumard’s oak—park president Mark Banta’s favorite, due to its fall color—is dropped into one site, its eventual, full-grown weight needed to be distributed. That might mean moving a water feature, or pathway, or placing lightweight grasses nearby.

Every planting created a conversation with the engineering firm, Elliott says.

The designers considered famed urbanist William H. Whyte’s works, particularly his 1988 manifesto, City: Rediscovering the Center. In it, Whyte argues that pedestrians only enter public plazas when they’re convenient, and inviting. Berms, steps, and inclines are a detriment to participation.

“The city is full of vexations,” Whyte wrote. “Steps too steep; doors too tough to open; ledges you cannot sit on … It is difficult to design an urban space so maladroitly that people will not use it, but there are many such spaces.”

Elliott says he and Burnett strived for seamless entry points.

“We didn’t want to have something that was elevated really high or sunk really low,” Elliott says. “That was our guiding light at that point—that the park was something people could just walk very casually into, that there were no steps or trip-hazards.”

Every third or fourth box-beam is lowered to accommodate the trees, Elliott says, without having to raise or lower the height of the park.

Then came the part of the project that everyone actually sees: the plants.

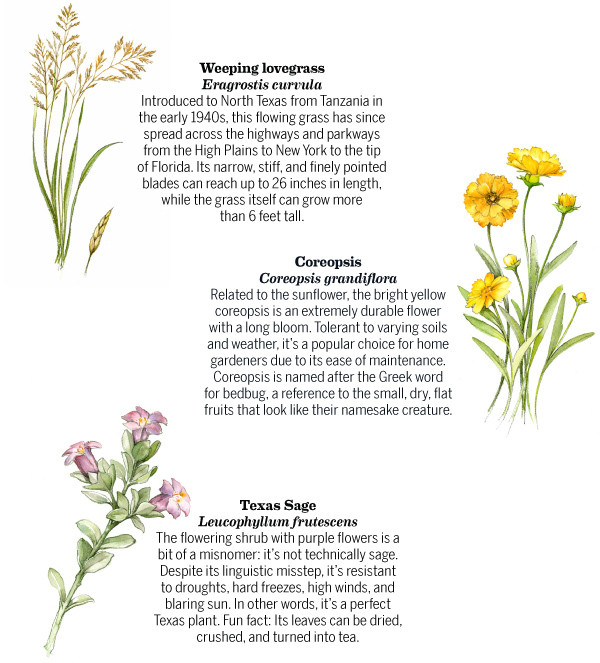

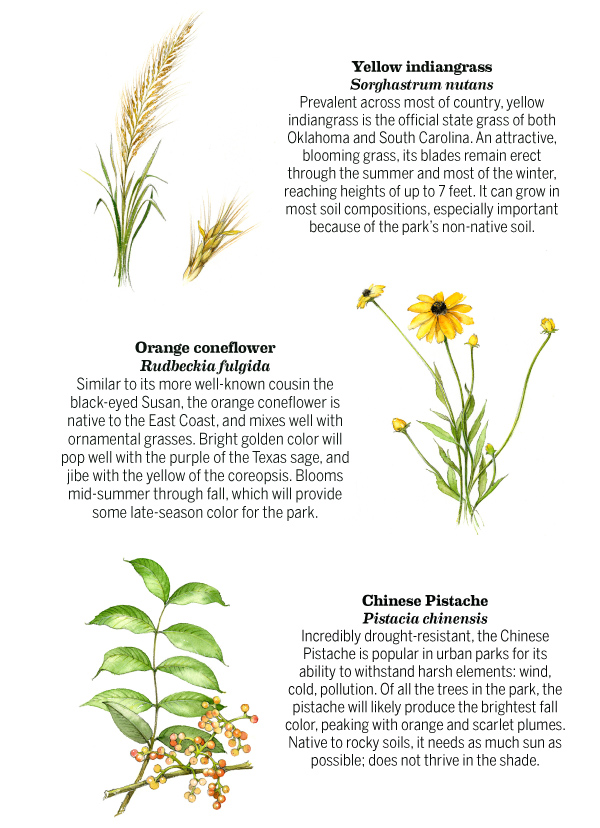

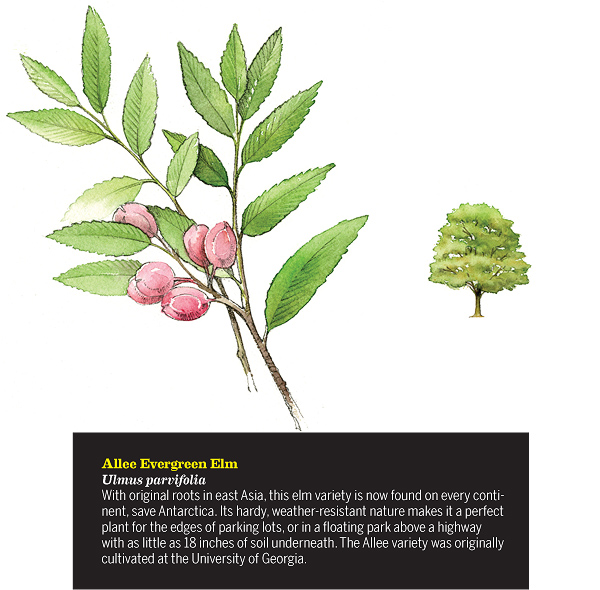

Drive along North Central Expressway, or any of its overpasses, and you’ll likely witness dying greenery, the byproduct of broken TxDOT irrigation systems and bureaucratic neglect. To combat that, the planners of Klyde Warren Park installed a complicated, high-efficiency drip-irrigation system, complete with computerized rain and freeze sensors. They met with Dallas Parks officials and the city arborist, to siphon their expertise on Dallas-resistant plants. And, finally, they found plants that could thrive on what is essentially a green roof over a freeway. The greenery also would have to withstand the wind-tunnel effect that any downtown park must endure.

“We picked materials that were all native or adapted to North Texas,” Elliott says. “There’s a variety of trees, and we also looked at all the shrubs, perennials, and grasses. Now there’s also the fact we’re on a bridge deck and, in some places, there’s only 18 inches of soil, or less. So making sure those selections were right was paramount.”

The most prevalent plant in the park is Texas sage, the poorly-named (it’s not actually sage) evergreen shrub nicknamed, appropriately for a Dallas park, Texas Ranger. The blooming plant requires little water and little care, a perfect plant for a park with limited size and irrigation. The other most-popular plants—weeping lovegrass, Indiangrass, coreopsis—are equally heat-resistant, flourishing along highways and streets from Florida to Texas.

Dura Heat River Birch and Chinese Pistache will raise the height of the park, with the latter providing a shock of orange leaves come fall.

“We anticipate that it’s going to be the front lawn for both people in Uptown, as well as workers and people living a little further south downtown,” Elliott says. “I think it’s going to be fairly spectacular.”

As their work wraps up, the landscape architects are leaving Klyde Warren Park in good hands.

Banta, prior to his 15 years as general manager at Centennial Olympic Park in Atlanta, worked in horticulture at the University of Georgia for 14 years. Klyde Warren Park also hired Michael Gaffney, formerly of Dallas-based Valley Crest Landscape, as vice president of operations.

“Selecting everything, making sure everything has a life support system, and then having people who know what they’re doing and are empowered to make those decisions—I think those three things mean that this is going to be a different kind of park experience for the city of Dallas,” Elliott says.

In the end, Elliott sees the park’s greenery as not only an emerald jewel for downtown, but also a learning experience.

“There’s an opportunity here for people to learn more about plants,” he says. “If you look at places like the Park Cities, it’s kind of pastoral, lots of turf, very, very green lush plantings. And that’s great, but it’s not native. We’d like to showcase how North Texas plants can be beautiful and functional and fit into the fabric of a city.”