The State Fair of Texas is one of the few independent fairs left, where no single company operates the midway. The broad alley of entertainment is filled by a free market of individually owned rides and games. Our midway is one of the nation’s largest, with space for both toddler rides that look like large-scale toys and towering roller coasters. This year, from September 28 till October 21, it will be packed with people from across and outside the state. And for the duration, hundreds of ride operators, food hawkers, and gamesmen log 13- to 15-hour days, suffering the squeals of fair-goers.

Some traveling workers stay in motels, but several hundred live in a matrix of house trailers abutting the fairgrounds, a boomtown that ebbs every fall. They are dutiful and diligent and opportunistic. They endure hazards particular to their vocations and maintain their own peacockish pride. Many are sold-out carnies who gladly assume the label. They are restless nomads who love to travel the country. Others are pinioned to Texas by job and family, fair-bound for only the one month that Fair Park flips from ghost town to festival.

Both types of worker, though, give the same response when asked why they endure the long, hot hours and nonstop cacophony: “It’s fun.”

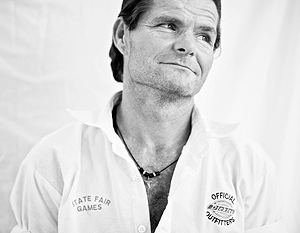

SURPERVISOR OF CRAZY MOUSE AND WINDSTORM

Mike Murphy, his fingernails yellowed from years of smoking, holds a smoldering cigarette as he watches his men work. One of the men casually dodges a swinging piece of steel that could easily ruin him. The roller coasters’ construction is a ballet of tubular metal. When both coasters are built, Murphy will return to his home in New Braunfels, until the fair is over and the deconstruction begins.

Murphy, who works about 10 fairs every year, moves his two coasters all over the country, setting up at fairs and carnivals along the way. He is a 44-year veteran of the American carnival. His career began when a friend bet him that Murphy could not last an entire season with the carnival. The Ohio-born ride owner has seen nine U.S. presidents take office since that bet, having worked his way from simple ride operator to small carnival owner to roller coaster baron. In that time, he has witnessed the evolution of the carnival.

“These coasters are operated by computers, one button,” he says. “Back in the old days, we used to have gas motors on them. You had throttles. Your Ferris wheels used to be gasoline powered. Your Tilt-a-Whirls used to be gasoline powered.”

Murphy has a tattoo of a carousel horse, a token not only of his carnival life but also of his collection of hand-carved carousel horses at his home. As a younger carnival worker, he spent his breaks reclining in a merry-go-round chariot, eating a sandwich, and reading a newspaper as the ride turned. He is a short man, slightly bent at the shoulders, with a scowling look that belies a gentle demeanor. He is a jokester with a tired, easy laugh.

“I’m semiretired,” he says, smirking, as he points to his nearby 18-wheeler. “There’s my semi.”

OPERATOR OF ROPE LADDER

Robert Collins steps onto a rope ladder with wooden rungs drawn taut at a slight incline to the ground and joined to a swivel at both ends. Standing upright, he walks up and down the ladder before hopping off and barking to the midway, “Who’s neeext?” Several people attempt the same feat, groping up the ladder with all four limbs. All of them capsize and are dumped to the padded floor.

Collins walks the rope ladder all day to draw in customers. During the especially long Texas State Fair, he goes to bed with aching knees and swollen ankles, often waking in the middle of the night with leg cramps. None of this dampens his enthusiasm. “I have fun doing this,” he says. “I can do it with one arm. I can do it blindfolded.”

The job has more serious hazards than leg cramps. Some carnival-goers, infuriated by the ease with which Collins climbs the ladder, have taken revenge. “I had a grown woman, she come over and snatched the ladder out from under me.” His leg got tangled on the way down. “Compound fracture,” he says, pulling up a pant leg to reveal a long scar. He then points to a nub on his forehead, a mark he received during a similar incident when he fell, head first, into the metal crossbeam above the buzzer that signals a win. Collins now keeps a 2,500-watt taser by his side. “You will not hurt me without getting lit up,” he says.

Collins spends his off-season at home on the Pacific Coast, using his balancing skills on a surfboard. But he is always excited to start the tour again. “Once it gets in your blood, you might get off the road for a year, maybe two, but you’ll always come back to it. It’s the camaraderie. There’s no better job than the one I’ve got,” he says.

“I’ll do this until my legs give completely out.”

RICH WRIGHT

OPERATOR OF ALPINE BOB’S

Before walking up the gangway to the operator booth, Rich Wright picks up a few cigarette butts and a stray peanut. He has operated Alpine Bob’s for two years and has a profound sense of his vocation, which includes keeping the ride clean. Wright is aware of what he calls the “toothless and crazy” reputation of carnies and concedes that it used to be accurate. “Drugs like crazy,” he says of the carnival era that preceded him. Now operators are tested at random, and their rides are inspected daily, a shift that Wright fully supports.

Carnies are a particular league, with their own tools and their own lexicon. Wright says the small booth where he sits is called “the dog box.” “We’re called ride Jacks,” he says, and gamesmen are “Joinees.” Wright’s forearm bears a tattoo of the Red Bull logo. The drink is a resource without which, he assures me, his job would be impossible. “Fifteen years I’ve been pounding Red Bull,” he says.

Wright has held several carnival jobs. He used to work on roller coasters, climbing without a safety harness to assemble the ride’s highest pieces. “I’ve fallen a lot,” he admits. “I just never hit the ground.” It’s a job he would like to do again. “I wanna climb that so bad,” he says, pointing to the Texas Star, the State Fair’s most iconic ride. “But I know they’d call the cops on me.”

Raised in Florida, he describes a good day as “pretty much every day.” No matter how badly a morning may go, he will always be smiling by midway’s close. “We’re fun-coordinators,” says Wright, whose best days are filled with laid-back riders. “You gotta deal with a lot of craziness,” he says. But from his vantage, the fun-loving folk always outnumber the others.