Before I met Robert Jeffress, I wanted to hate him. Jeffress is the conservative preacher who made national headlines in October, when he called Mormonism a cult. He’s the senior pastor at First Baptist Dallas, the oldest megachurch in America, and I am certainly not a Baptist. He endorsed Rick Perry for president, and I’m definitely no fan of Perry’s. As a matter of fact, Robert Jeffress and I probably disagree on every major political and religious issue. And yet, I really, really like him.

It would be easy to dislike him if he were a hypocrite or a bigot, if he were an insufferable megalomaniac or the kind of man who preaches out of hate and anger. But he’s none of those things. He’s actually delightful to be around. He’s not just polite; he earnestly cares about people. He may not believe in evolution, but he really does want to know how your day has been. He may oppose certain rights for gay people, but he genuinely desires for you to be merry on Christmas. If he talks with you, he’s attentive and giving. He’s curious about you and about the world.

The first time I met him, he greeted me warmly, even though he’s the next Jerry Falwell and I look, as one of his staff members put it, “like the son of David Crosby.” He looked past the beard and long hair and shook my hand firmly, inviting me into his spacious office. He offered me soda, coffee, water, a seat on his comfortable leather couch. When I noticed that he had the jackets of all 17 of his books framed and hanging on a wall, I mentioned casually that I’d love to write a book someday. He tilted his head slightly and looked into my eyes.

“Oh, you will, Michael,” he said. “I’m sure of it.”

Jeffress was so confident, his voice so unwavering, that I couldn’t help but imagine for a few seconds what it might feel like to have a freshly printed book with my name on the spine.

Without seeming the slightest bit intrusive or incredulous, he wanted to know about me: where I grew up, what I studied in college, where I’d worked, and whether I’d enjoyed the jobs. When the conversation finally turned to him, he told me I could ask him anything. That afternoon, we talked for nearly two hours straight.

It turns out that there is a lot people don’t know about Robert Jeffress. He’s a fan of game shows, for example. He has appeared on two. He likes taking his daughters to Broadway musicals every year around Christmas. He watches what he eats and runs 3 miles on a treadmill five days a week. He’s well-versed on both pop culture and current events. He’s also self-deprecating, quick to joke about congregants falling asleep in the pews or the nerdiness of his own accordion playing.

Aside from his charisma and intellect, what makes Jeffress different from most people—even a lot of self-professed Christians—is that he is absolutely certain that Hell is a real place. He’s certain that a lot of good, moral people are going there—and that he is not. He really doesn’t want you to go to Hell. More to the point, he really enjoys saving people from eternal damnation.

A lot of the more prominent evangelists these days seem more like motivational speakers. Some of the more popular—the Joel Osteens of the world—hardly mention Jesus until the end of their sermons, and many never mention Hell. But Jeffress believes that End Times are coming, and that there will be a reckoning for all eternity.

“Like Harold Camping, without the crazy, then?” I asked him, referencing the California radio evangelist who has, several times, incorrectly predicted the exact date of the end of the world.

“Like Harold Camping without the date,” he clarified.

So you have to understand, when Robert Jeffress says things like “Mitt Romney is not a Christian,” or “Islam is a false religion based on the teachings of a false prophet,” or that Oprah Winfrey is “a tool of Satan,” he’s not just trying to say something bombastic because he likes the attention. He says it out of love. He truly believes the culture is in decline and that he is slowing the decay and that this could prevent you personally from spending forever with your flesh on fire.

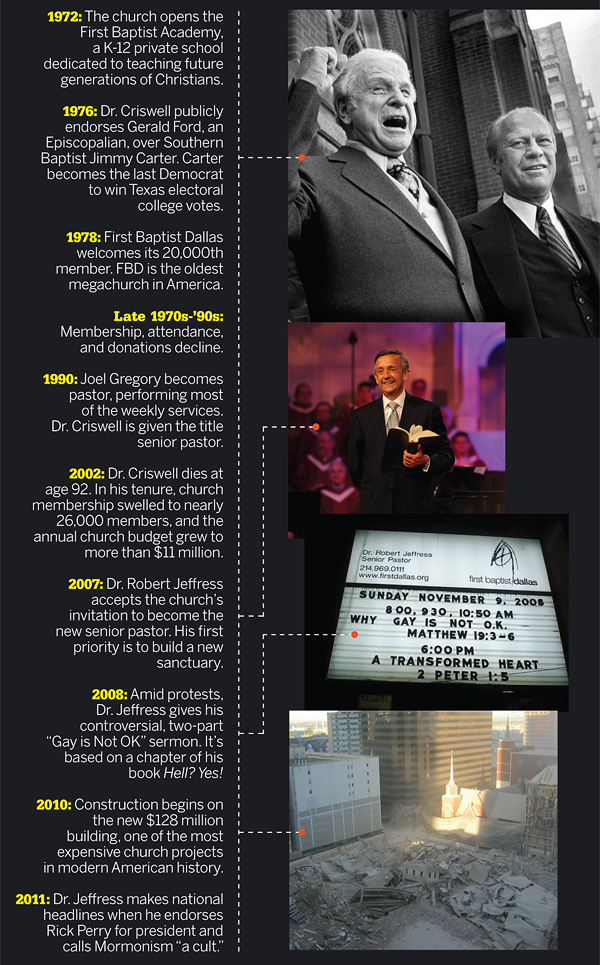

It’s the reason Jeffress has his own radio show, his own television show, and why he’s about to publish his 18th book, Twilight’s Last Gleaming: How America’s Last Days Can Be Your Best Days. It’s the reason First Baptist Dallas recently decided to undertake one of the most expensive church construction projects in modern American history. At a cost of $128 million, the new campus will feature a glass skywalk, a giant cross-shaped fountain, and a sleek 3,000-seat sanctuary that will rival Madison Square Garden. Jeffress wants it to serve as a “spiritual oasis” in the middle of downtown.

See, if you’re gay or Muslim or you just don’t believe, as he does, that every word of the Bible is literally true, Jeffress doesn’t hate you. He has never hated anybody. He just wants you to come to Jesus. In 2008, when he gave his two-part “Gay Is Not OK” sermon, he told his church: “What they [homosexuals] do is filthy. It is so degrading that it is beyond description. And it is their filthy behavior that explains why they are so much more prone to disease.” But seconds later he reminded the flock to “demonstrate compassion,” noting that “cutting off your children is the biggest mistake you will ever make. You don’t have to approve of what they’re doing. You don’t have to invite their homosexual lover into your home. But let your son or daughter always know that you love them.”

The morning he first gave that sermon, there were about 100 protesters gathered outside the church. They held rainbow flags and signs reading “My Gay Child Is OK” and “I’m still a lesbian. Maybe you aren’t praying hard enough!” The church hired off-duty police officers and served the protesters coffee.

“If there really is no Hell, then it’s judgmental and unloving to tell people what they believe is wrong,” he explained to me early on. “But if you really believe there is only one way to Heaven, and it’s through faith in Christ, why wouldn’t I want to warn everyone I could?” He paused for emphasis. “This is the only way out.”

See that? Because he knows for sure he’s right, he can—no, must—tell others they are wrong. Even if you wanted to argue, certitude cannot be negotiated with. But you don’t want to argue, because that kind of confidence is intimidating and contagious all at once.

This is nothing new to Robert Jeffress. He has known for sure what he wanted to do with his life since he was a freshman in high school. He knew the woman he wanted to marry when he was 15. In fact, as far back as anyone can remember, he has been the walking embodiment of certitude. Even close friends and relatives are hard pressed to remember a single time when they saw him doubt himself, even for a moment.

When I first asked the church for an interview—about the time he was making the rounds on the cable news shows, explaining himself in the wake of the “Mormonism is a cult” controversy—I was hoping I might be able to spend enough time with him to get to know the real Robert Jeffress. I knew he couldn’t always be that sweet, cheerful guy I saw on TV.

His saccharine disposition is often the subject of jokes. After playing a clip of Jeffress saying Mormonism has always been considered a cult, The Daily Show’s Jon Stewart called it “the sweetest, most good-natured, pleasant sh—ing on an entire religion I’ve ever seen.” He added, aping Jeffress’ syrupy Southern twang: “Bless his heart.”

In the days I spent with him, sometimes from sunrise to sunset, he convinced me that the bright-eyed schoolboy persona is not an act. He decided very early on that he was a Christian, and though he has grown intellectually (he has several postgraduate degrees in theology), he has never changed his mind. On anything. Ever. That said, he still enjoys the company of people who see the world differently.

Jeffress has made dozens of appearances on FOX News, CNN, and MSNBC (he really likes Chris Matthews), but his favorite might have

been in October, when he accepted an invitation to fly to Los Angeles to shoot a live segment on HBO’s Real Time With Bill Maher.

Maher, an atheist who wrote, produced, and starred in Religulous, a documentary mocking organized religion, welcomed Jeffress to the show. The pastor came on wearing a sharp navy suit, a bright red tie, and his trademark smile. Maher presented Jeffress with a copy of Religulous on DVD.

“Now, you might hate, like, the first 93 minutes,” Maher said.

“But the credits are great, right?” said Jeffress, not missing a beat.

Soon the conversation turned to Jeffress’ most recent comments on Mormonism. (He has actually been calling Mormonism a cult on camera since 2007, and he has never once backed down or retracted.) The reaction of conservative pundits such as Karl Rove and Laura Ingraham was sharp and critical.

“Since I made those comments, the left has been pretty kind to me,” Jeffress said. “It’s been the conservatives who are after me with a meat cleaver.”

Maher interrupted to high-five the pastor: “Right on, brother!” The sight had the crowd howling with laughter.

After the live show, Maher invited the pastor to sit on a panel for the “Overtime” segment. They put him between Maher and 6-foot-7 magician and dedicated atheist Penn Jillette. To make matters more interesting, Jeffress’ chair was several inches shorter than the others’, making him look even more like a little boy sitting at the adult table.

But it didn’t seem to faze Jeffress. Someone suggested that the pastor has such good chemistry with Maher that they could have their own show. Maher joked that it’d be a morning show, like Live With Regis and Kathie Lee. Jillette chimed in to say he thought it should be a buddy-cop movie, feigning the throaty voice of a movie trailer: “He’s an atheist. He’s a Christian. But they’re both—cops!” Then Jillette and Maher both posed around Jeffress, Charlie’s Angels-style, with their finger guns in the air.

After the taping, Jeffress brought his wife and 19-year-old daughter to the show’s rather legendary after party. Maher isn’t shy about his drug use—Zach Galifianakis smoked a joint live on his show in 2010—or his affinity for adult entertainers. But there was Jeffress, sipping from a bottle of water, delighting these Hollywood liberals for half an hour. Maher was so charmed by Jeffress that he nearly missed a flight.

When he got back to Texas, Jeffress wrote Maher a letter to tell him what a nice time he’d had. He thanked Maher and told him he would indeed watch his movie. He said he planned to get a warm cup of cider and watch it on Christmas Day.

To understand why Robert Jeffress is the way he is, you have to see how predetermined his life can seem and how little he’s changed since he was a boy. Born in 1955, he came up in First Baptist Dallas when it was becoming the single most important evangelical church in the country, the heart of the conservative Christian movement in the 1960s and ’70s. Jeffress grew up within the walls of this church. He was baptized here, married here, ordained here. He got his first job out of college here, preached his first Sunday service here.

“He was always doing something around the church, always excited to share the message of the Lord,” says Nell Stephens, a sweet woman who has been a member of the congregation for nearly 50 years. “He’s always had that warm, happy smile, too.”

His parents were both members of the church before they had him. His dad had finally convinced his mom to join after a Billy Graham revival at the Cotton Bowl, when Graham himself declared that he wanted Dr. W. A. Criswell to be his pastor. “My mom decided right then and there, if it was good enough for Billy Graham, it was good enough for her,” Jeffress tells people.

His mother graduated high school when she was 15 and graduated from SMU when she was 18. She took a job teaching journalism at Hillcrest High School, eventually becoming one of the more beloved teachers in school history. It was from her that Jeffress got his charisma, his quick wit, his appetite for current events.

His father was a flight dispatcher for Braniff International airlines. He smoked and drank the occasional beer. Within a week of Jeffress’ birth, his father flew on an employee pass to Chicago, to go to the Moody bookstore. He came back with more than $200 worth of Christian books for the newborn.

When he was 5 years old, little Robert became a Christian. He remembers it started with a conversation he had with his dad at the dinner table. Then he walked down the aisle that Sunday at church, to tell Dr. Criswell he had accepted Jesus into his heart. Criswell had the boy and his father come by his office. He asked Robert a few questions, to see if he knew what he was talking about. Then, Jeffress remembers, Criswell kneeled beside him to pray. Afterward, Criswell warned the boy: “Now, Robert, don’t let me see you walking down that aisle again one day because you slipped up.” Little Robert nodded.

He was a smart kid, with great grades. His brother, Tim, is three years younger. Tim remembers their mother going from room to room to wake everyone up for church on Sunday mornings. “But she never had to wake up Robert,” says Tim, now a lieutenant with the Dallas Police Department. “I’d be lying in bed, begging them to let me sleep in. He’d be standing there, fully dressed, waiting for the rest of us.” After the family got back from church, Robert would watch Meet the Press, and his mother would make him a grilled cheese sandwich.

Jennifer McKellar is the pastor’s sister, younger by six years. She remembers his incredible talents on the piano. He has always been able to play by ear. “For years, he couldn’t walk into a room with a piano in it and not sit down and play some show tunes,” she says.

He kept himself busy as a teenager. In addition to all the time he spent at church or playing the accordion, he had a job at a Christian bookstore, he was on the debate team, and he organized a group dedicated to beautifying the school campus. He never fit into one of the groups or cliques, but he seemed to get along with everyone.

He came of age in a time of the sexual revolution, in the days of free love and open drug experimentation. But Richardson, Texas, wasn’t exactly the center of counterculture. He says those things just never really occurred to him. He’s never taken a drug or had anything harder than Jack Daniel’s ice cream in his life, and perhaps the only time I saw Jeffress uncomfortable was when he mentioned his battle with hormones as a teenager.

For him, he explained, nothing feels better than a conversion. A teacher once challenged young Robert to find five students who weren’t Christians, and to befriend them and pray for them and invite each one to Christ. One of the people on his list was a girl from his math class named Amy. She would later tell him she had never met someone so certain he was going to Heaven. He eventually brought her to an evangelical event at the church, and she became a Christian. (He’s proud to say that all five targets pledged their hearts to Jesus during the course of the school year.)

Between his freshman and sophomore years Jeffress felt God calling him to the ministry. He says God has spoken to him only three times in his life. He knows it must sound crazy to an unbeliever. People always ask him if that first time was audible, and he tells them, “No, it was much louder than that.” The second time was when he was a freshman at Baylor University, when God told him that one day he would be the senior pastor at First Baptist Dallas. The other time was so personal, he told me, that he will never talk about it with anyone.

Jeffress couldn’t wait to tell Dr. Criswell that he felt called to the ministry. He tells the story often. “Dr. Criswell looked at me,” he says, “and he said to me, ‘Robert, I want you to get to know every square inch of this church this summer, because one day it will all be yours.’ ”

When Jeffress got to high school, he asked Amy on a date—to a debate banquet at which he would be receiving an award. Later he produced a musical variety show at the school called Love Is a Four-Letter Word. At one point the curtain rose on him dressed in a tuxedo, crooning “Strangers in the Night” directly to Amy.

“Robert’s always been very goal oriented. It’s like he came into this world as a little adult,” says his sister, who lives in Tyler and is married to a theology professor. “The essence of who he is and what he values has not changed since he was a kid.”

It was only a year or so after he got the first church of his own, in Eastland, Texas—Jeffress was a baby-faced 29-year-old pastor with more confidence than they’d ever seen—that his mother was diagnosed with cancer. He and Amy were married by then and living in the parsonage in Eastland.

“Robert and his mom were extremely close,” Amy says. “That was probably the hardest time in his life.”

“It’s like they shared the same spirit,” his sister says.

But nobody remembers his acting strangely or breaking down when she died in 1986. “He’s always been that mature, take-charge, older brother type,” his brother, Tim, says. “Some people are just made for certain roles in life.”

Everyone grieves differently. Some people drink. Some people wear black. Jeffress did what any good kid, missing his mom, might do. He escaped into a puzzle. Not long after the funeral, he decided he needed a new car. He had about $1,000 in the bank. Instead of buying a used car or taking out a big loan and going into debt (he likes to point out that while at Baylor, he double-majored in communications and business), he just knew he could win the money on a game show. He was sure of it.

He studied all of the popular game shows at the time and learned that a show called Card Sharks offered the largest daily cash prizes. He taped the show with his VCR every day and watched each episode over and over. He learned what kinds of questions the contestants usually faced, which strategies generally resulted in the biggest wins. Eventually, he bought himself a plane ticket to Los Angeles and went to a tryout. (Coincidentally, the show was taped at the same CBS studio where Bill Maher’s show is now shot.) There were more than 200 people there that day, but he was one of three chosen to be on the show. When they picked Jeffress, producers told him to bring five sets of clothes with him, because they shot an entire week’s worth of episodes all at once.

As always, his confidence and preparation was rewarded. He became the four-day champion, winning more than $4,000 in cash—and made it home in time to preach that Sunday. He used the money to make a large down payment on a maroon Oldsmobile Eighty-Eight. His episodes still rerun every so often on the Game Show Network, and once in a while someone asks about it. Of course, the people who know him best know that Card Sharks wasn’t Jeffress’ first game show experience. He once appeared on Let’s Make a Deal dressed as a banana. It’s hard to dislike a man who would go on national television dressed as a banana.

Jeffress didn’t start making enemies until 1998. By then, he’d been called to leave Eastland and become the pastor at the First Baptist Church of Wichita Falls. For the first 15 years of his ministry, he never got political in the pulpit. He didn’t mention abortion or homosexuality once. But two library books changed that.

He had just finished preparing a portion of a sermon titled “We Cannot Condone What God Has Condemned” when a member of his church came to him one morning with two books from the Wichita Falls public library. The books, Heather Has Two Mommies and Daddy’s Roommate, are both about children raised by gay couples, and the latter features an illustration of two men in a bed together.

“Homosexuality violates the teaching of three of the world’s major religions,” Jeffress says, when talking about why he did what he did. “It’s responsible for one of the great epidemics of all time, and it was also illegal at the time.” (Anti-sodomy laws have since been ruled unconstitutional.)

He thought about those books. And when he was preaching his message that Sunday, something welled up inside of him. The words just came out. “I’m gonna take my stand right here!” he said. “I’m not gonna return these books!”

He offered to pay the library for the books, and asked the librarians to not use the money to buy more copies. The librarians would agree to no such thing. Soon the City Council was involved, passing a church-supported ordinance that would require certain books be kept in a special “Adult” section. Then the ACLU got involved, and the story made national headlines. There were regular editorials and letters to the editor about it in the local paper, a nonstop stream of arguments both for and against Jeffress.