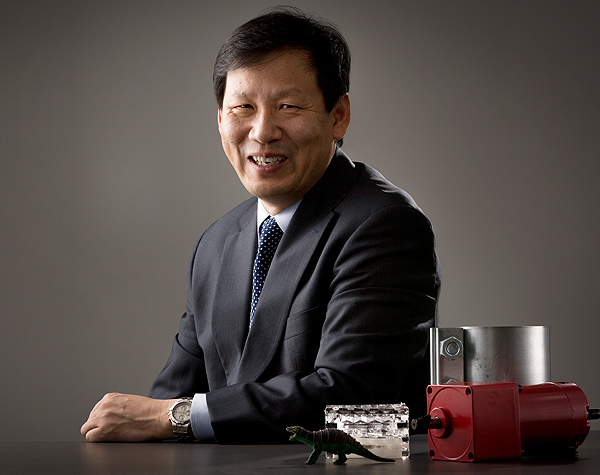

On the ground floor of the sprawling Dallas Market Center, Ray Sun, a smallish, friendly man with a youthful demeanor, was standing just outside his products showroom. Nearby his display window exhibited an array of precision machine parts, all gleaming and stainless steel, as well as a child’s board game featuring dinosaurs.

Each of the displays has a creation story that Sun, 55, was eager to tell to a visitor one recent day. But when he was informed that his guest was a journalist, something extra lit up in Sun, who’s the owner of a Plano-based consulting firm called Advantage China. He insisted that the reporter head straight for the Center’s fourth floor to meet with two clients who, he proclaims, may have a hit on their hands at the Center’s big gift show in January.

That chance encounter was intriguing to this writer. But it offered little hint of the colorful, dramatic route that Sun has followed from the teeming streets of Shanghai to studies in Montreal to serial business failures as a Toronto software entrepreneur to Dallas, where Sun has become a self-made, if belated, success in international commerce. In a nutshell, Sun has made it his business to make China work.

And, he’ll make it work for anyone—from the U.S. units of Swiss-based multinational corporations to suburban Dallas housewives who think they’ve got the Next Big Thing. He’s currently overseeing 20 projects, which he expects will triple revenue to eight figures for Advantage China next year, when several projects will go into full production. The two local women with whom Sun urged a meeting, for example, sold decorative items with a wholesale value of $7 million in their second year in business, after developing a product line with Sun’s help. Then there are medium-sized companies that need to remain competitive with rivals already outsourcing to Asia, or others who can’t quite find someone—in the United States or abroad—who can turn their idea into a marketable, blister-packed product priced to sell.

Sun says he can get a plastic prototype made in China for a fifth of the cost in the United States: $2,000 versus $10,000. For many would-be entrepreneurs, he says, the latter price would “kill” a project before it got off the ground. And that’s why he’s so valuable, he insists, to North Texas businesses. Among them: a company that supplies equipment for power plants, and another that makes a gadget for laying tile on mall floors.

Understanding The Process

Working as a transpacific consultant wasn’t Sun’s original idea when, in 2004, he followed his wife, a physician with two medical specialties, to Texas. Here, she took a position with a Fort Worth hospital. Using his software background, Sun built a website offering thousands of Chinese-made products. But he found few buyers. When he began offering his personal services as a hands-on go-between, however, Sun felt he had struck pay dirt. His first contract was for the creation of non-stick camping cookware for a Colorado maker of freeze-dried meals for hikers. His Shanghai-based staff of two—it since has grown to 10—identified four manufacturers with the ability to produce the plates and pans. When all the pieces arrived from various points, a warehouse was rented for a day, and temporary workers assembled the kits. “I made no money on that order,” Sun recalls. “But it made me fully understand the process and gave me confidence that I could do it.” Years later, the sets are still being made and sold.

Sun knew that finding a supplier is often less than half the job. Quality control remains an elusive concept in a country that is making great, but jagged, leaps from Third World practices to cutting-edge processes. Thousands of suppliers rely on networks of mom-and-pop workshops of varying reliability, few with any meaningful reviews or independent testing. Yet Sun discovered a small Chinese village that specialized in rubber products that meet American standards, for instance. Villagers there turn out countless window squeegees of “very good quality,” he says. And although a large manufacturer won’t set up a production line for a small order, hamlet workshops are more than happy to get the work.

Corruption and red tape are less a problem for him in China than spotty, or nonexistent, quality control, he contends. Another complication is that only a limited number of companies have coveted export licenses, necessitating the payment of a fee for their use, ranging from 1 percent to 1.5 percent of the shipment’s value, he says. A food product would be a different matter, particularly after all the toxic contamination scandals in recent years. Foodstuffs require a myriad of licenses and protocols, which somehow still fail to stop periodic unsafe food incidents that plague China. For that reason, Sun steers clear of edibles and commodity imports.

Still, there are countless ways an unwary foreign importer can be cheated when bringing in non-food items. If it’s made of plastic, Sun asks, is it made from inferior, recycled material? The answer: “They don’t tell you.”

For first-timers trying to get an item fabricated, there’s the problem of where to begin. When prospective U.S. buyers use such popular Internet sites as Alibaba to source a product, they’re unaware that more than half the listing companies are brokers, not actual

manufacturers, Sun says. “You can’t do business by phone or email. You have to go there, wherever it is, and meet them face to face,” Sun says. Only then, he adds, can you size up the operation and its ability to deliver.

“Ray Sun is right,” attests Jeremy Haft, an American consultant who has run companies in China for the last 15 years and teaches at Georgetown University. “How big is the quality control problem? Huge. It pervades China’s entire industrial and agricultural base. It goes way beyond just the attitude of the workers. One cause is severe fragmentation. So, take a look at a pen on your desk. This might take three players to make in the U.S.” But in China it could take 15, Haft points out in an email. “All the sub operations occur at separate plants. Plus there are a number of middlemen involved in the distribution of the raw materials and the final product. Each player in the chain adds risk, time, and cost.”

Sitting down with a would-be entrepreneur in Dallas or Denver, Sun says, he can bring an immediate reality check by factoring in likely manufacturing and shipping costs, then contrast that figure with what the object could fetch on the U.S. market. His napkin-back spreadsheet requires a U.S. selling price that’s six times the cost in China, or the venture will fail.

His clients four floors up at the Market Center, for example, were two Plano women who, frustrated at the poor selection at major craft chains of decorations and accessories for their middle-school daughters’ school lockers, designed their own products under the Locker Lookz brand. All they needed were manufacturers to turn their idea into a full line of mixed and matched “wallpaper,” mirrors, miniature chandeliers and other gewgaws that only pre-teens crave. Attempts by Joanne Brewer and Christi Sterling to find a U.S. manufacturer that could produce the tiny lights proved fruitless. Sun, by contrast, found innovative Chinese companies that pulled it off.