Chris Cantalini launched Gorilla vs. Bear from his cubicle while working a mundane, Office Space-style day job in 2005. He had time to kill and a fast internet connection, so he trawled for music acts he liked and posted their songs on his fledgling site. Ten years later, that’s more or less what Cantalini still does.

“I just post when something moves me to do so,” he says.

Then as now, Cantalini is nearly absent from his own site. He rarely offers much commentary and doesn’t let his personality get between his readers and the music he is sharing. While his selections can be eclectic—from highbrow hip-hop to plasticized electronic dance music—there is certainly a Gorilla vs. Bear aesthetic, which leans toward dreamy synthesizers, waifish female vocals, and introspective pop.

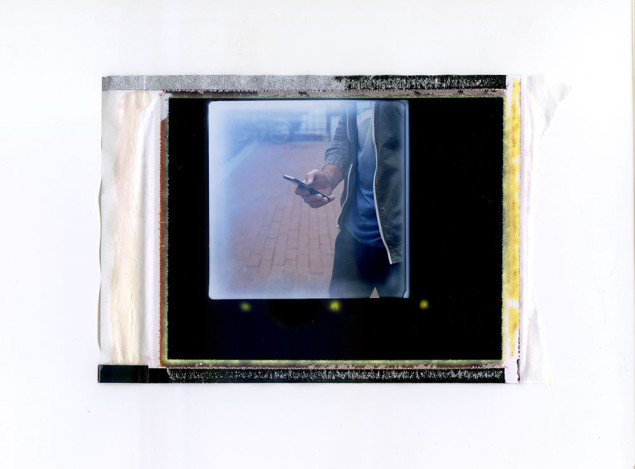

That sound is deftly complemented by the site’s use of Polaroid photography—an addition of David Bartholow, who joined about six months after the site launched. The total package evokes a kind of nostalgia and hip sentimentality that is perfectly millennial and has almost become cliché. But their commitment to that audio-visual combination is how the site has been able to project a feeling of relevancy that has proven relatively timeless.

“Everything from our musical taste to the aesthetic vision really just amounts to what David and I think is interesting or cool or moving at the time,” Cantalini says. “And I think we’ve been able to maintain that over time by not diluting it through overextending ourselves or clouding the vision with additional contributors.”

A decade later, that unclouded vision has turned Cantalini from office drone into noted tastemaker. He now hosts a radio show on SiriusXM, and his attention is courted by up-and-coming bands and industry professionals alike. This month, his site celebrates its 10th anniversary with the fifth installment of the Gorilla vs. Bear music festival at the Granada Theater, headlined by English electronic music producer Jamie xx.

And yet, despite its international influence, Cantalini’s site has been rejected a bit like a prophet in his hometown. When he launched the first Gorilla vs. Bear fest five years ago, the Dallas Observer wrote that Cantalini’s site “doesn’t really touch the Dallas music scene.” The Dallas Morning News poked fun at Cantalini’s low-key local profile by calling the website “Earthworm vs. Mole Rat.” One year later, the city’s daily called an installment of the website’s festival, whose lineup was filled with female lead singers, “Girlapalooza” (as if the opposite version would ever be called “Manapalooza”).

Let’s put aside for a moment that the criticism that Gorilla vs. Bear has ignored local music is flat-out wrong. From Neon Indian to St. Vincent to Leon Bridges, Gorilla vs. Bear has not only featured bands from North Texas over the years, it has played a major role in garnering them the kind of attention that has led to full-fledged careers in the music industry, even if many of these acts eventually decided to pick up and move to Brooklyn.

No, the problem some locals have with Gorilla vs. Bear probably stems from the fact that, during its rise to prominence, the entire way we listen to, discover, and relate to music has irrevocably changed. It never really mattered where Gorilla vs. Bear was located. In fact, many people assumed that a site with its particular sensibility and knack for spotting hip, trending artists was based out of Brooklyn or Portland. But Gorilla vs. Bear could have been founded anywhere precisely because it came about at a time when music “scenes” as we have traditionally understood them matter less and less.

There was a time when cities that produced a handful of bands that got attention—think Seattle grunge or even Deep Ellum in the late 1980s and early 1990s—could leverage their location as a calling card. They could cultivate a sound, score a couple of breakthrough acts, and then record-label A&R reps would try to capitalize on growing momentum. It was easier to parachute into a buzzing city and take advantage of a target-rich environment than it was to sift through demo tapes and hoof it to far-flung corners of the world in search of a new sound.

Gorilla vs. Bear was out in front of a monumental shift in the way music happens. Culture has migrated into a digital space, which means that everything is now instantly accessible to anyone anywhere. You can be a musical tastemaker and never actually go to concerts. You can discover bands from Norway in a cubicle in Dallas. This access not only affects how we discover bands but also what the music we discover sounds like. There is less regional distinctiveness in music produced today. When a 14-year-old in Denton can find out what punk sounds like in Hong Kong with a few clicks of the mouse, the cross-pollination of musical influence is no longer tied to geography. In fact, one of the curious aspects of Gorilla vs. Bear’s influence is not only that it has been able to consistently find bands that appeal to a certain sensibility, but that by pulling together all of these musical acts into a single space, it has participated in creating its own sound, its own digital music scene.

Gorilla vs. Bear’s success is bound up in what you might call internet culture’s myopic inertia, the way that an individual’s particular interest—however obscure—can always seem to find a community of like-minded obsessives somewhere online. “Curation” is a word that is grossly overused these days, but the very thoughtful and careful selection of what goes on Gorilla vs. Bear is the site’s main appeal.

“I feel like we managed to establish a genuine and distinct voice at the right time, and people responded positively to it,” Cantalini says. “We try not to pay too much attention to the reception outside of the feedback and engagement we have directly with people who are actually visiting and reading the site.”

The Gorilla vs. Bear festival extends that attitude to a live setting, as Cantalini chooses the lineups simply based on the acts he likes and still manages to pack the house. That the fest has garnered so much support locally should serve as a reminder that this is a more eclectic and tuned-in city than some Dallasites give it credit for. In that sense, it should be no surprise that the biggest thing in music to come out of Dallas in the last decade isn’t really about Dallas music.

And it doesn’t matter. The success of Cantalini’s website has always been about finding and promoting good music. What does that mean for the city? This month it means Gorilla vs. Bear will help bring more good music to Dallas. Who can complain about that?

A version of this column appears in the July issue of D Magazine.