Most film critics are list fetishists. And while I do enjoy stacking up movie titles at the end of the year, it’s also a frustrating holiday ritual. First off, I’ve seen a few hundred movies this year, and yet inevitably a few slip by that, based on the buzz they are receiving, I suspect would rank on this list. This year those include feature films like Tabu and Once Upon a Time in Anatolia and documentaries like Brooklyn Castle and This is Not a Film.

Also, going over all the movies I saw this year, it was hard to let some go unmentioned. Sure, Steven Soderbergh had a great year with Magic Mike and Haywire, but how do those compare with The Turin Horse? I was also big fan of the insanely exciting Indonesian martial arts film The Raid: Redemption, but how do you compare that with Bernie? Then there are the films you list because, despite their flaws, they have a particular personal resonance. Sarah Polley’s adept direction of Take This Waltz, and Michele Williams’ endearing performance in that film, have not garnered mention on many other year-end lists, but the movie stayed with me for so many months I couldn’t leave it off mine.

Finally I decided to split up fiction films and documentaries this year. I tend to like docs more than fiction films and end up cramming my top lists with non-fiction. So I wanted to see what would happen I couldn’t stack the deck with documentaries like How to Survive a Plague and The Ambassador.

And so, with all of that out of the way, here are my top 25 feature films of 2012.

(Go here for my top documentaries of 2012.)

1. Amour (Dir. Michael Haneke)

Haneke’s quiet movie about a dying woman and her devoted husband is simply unshakable. In it we encounter two of the most subtly rendered characters on screen this year, and their last days inside a modest Parisian apartment reveal so much about human interrelation. Here Haneke’s penchant for starkly-drawn worlds allows for an exploration of character and affection that resists sentimentality and nostalgia. Instead, his straightforward rendering lays bare our longings, frailties, fears, and failings.

There are plenty of movies this year that try to engage with the peculiar confusion of contemporary life – from blinding violence to a splintered sense of self – but Haneke’s film reminds us that perhaps what we often fail to grasp is a nuanced appreciation of the nature of a love that is hard-bearing, sacrificial, violent, open-ended, enigmatic, and necessary.

Dallas release date: Jan 18

2. Holy Motors (Dir. Leos Carax)

Leos Carax’s Holy Motors is befuddling, enrapturing, diabolical, exhilarating, infuriating, and beguiling. It is a movie-riddle that strikes at something unsettling close to the core of existence. In it, Denis Lavant delivers the year’s best singular performance as a hard-to-pin-down actor who glides through Paris in a stretch limo, performing living scenes. It takes a while to begin to understand what Carax is up to with his film, which breaks down our expectations of what we take to be “true” or “real,” initially in a cinematic sense, and then more broadly. Lavant plays a businessman, an actor, an artist, a performer, a beggar, a thief, a murder, a father, a scoundrel, a lover, a dying relative. He is lived contradiction, honesty manifested as a lie, whose presence serves as a foil both to society and existence.

Holy Motors is an unholy satire, an elusive and beguiling critique of life itself. Through his character, Carax breaks-down his audience, spinning Holy Motors into a carnivalesque hall of mirrors, an image play about images. “What is beauty if there is no beholder?” Lavant’s character speculates at one point. The answer that emerges in the movie is that beauty is something equal parts seductive and horrifying — horrifying, perhaps, because, as we fear (and begin to suspect), in the context of Carax’s vision of reality, it may be nothing at all.

3. Zero Dark Thirty (Dir. Katheryn Bigelow)

There has been no small amount of controversy surrounding Katheryn Bigelow’s new film. Objections have been raised regarding its depiction of torture, its glorification of war, its blurred moral stance on human rights, its possibly racist depictions of Muslims, its conflicting characterization of feminist vigilantism, its suspected historical untruths and journalistic indiscretions, its flagrant breaching of national secrets, and what might be characterized as callous patriotic blood-lust.

The reason for all of these muddy and uneasy reactions to Bigelow’s movie is that while Zero Dark Thirty appears in the form of an exciting Hollywood movie about search and capture of Osama bin Laden, it is equally a challenging critique – of the institutional structures that drove the manhunt, of the structure of human reason and capacity for understanding that deciphered the riddle of bin Laden’s location, of the seek-and-destroy mentality that ended up leading a team of Navy Seals to the hated terrorist leader. And while Zero Dark Thirty is ostensibly a movie about hunting for bin Laden, it is also a piece of entertainment that raises its very entertainment as a crucial point of moral questioning. If hunting and killing bin Laden was a victory for America, than Americans share complicity in the murky and unsettling means to that end. This is war, and the movie’s nearly real-time battle scene reminds us that war’s exhilerations are mined from war’s essential banality. And as Bigelow’s main character — magnificently portrayed by Jessica Chastain – grasps, war is a moral mess that glorifies the application of decisive and uncompromising will.

Dallas release date: Jan 4

4. Lincoln (Dir. Steven Spielberg)

Lincoln is a humanizing film, not merely in so far as it gives flesh and personality to a long-canonized historical figure (rendered with a depth and charm by a great actor in top form), but how it breaks history into its constituent parts, recreating the tangle of ideas, emotions, interests, and influences at a pivotal moment in America. Part historical drama, part rich ensemble piece – and beautifully shot by Janusz Kaminski, whose crisp, idealizing visual style finds its ideal material – Lincoln’s real strength is as political drama: a dialogue — a riveting, almost Socratic grappling with the mechanics of governance. Sure the director shows a slight wavering towards sentimental subplots involving his tired obsessions with fathers and estranged sons, but when dealing with a story about the father of a country in a nation torn apart, these are allegories easily swallowed.

5. The Kid With a Bike (Dir. Jean-Pierre Dardenne & Luc Dardenne)

The latest film by the Dardenne Brothers, who are perhaps my favorite living filmmakers, is a warmer, more hopeful movie than some of their earlier films, but it is nonetheless defined by their distinctive tone — a hard, visceral sensibility. With their forlorn characters, vulnerable and simple, estranged from the typically-portrayed Europe and occupying a strata beneath the thin veneer of bourgeois civility, the Dardenne’s present a vision of the world that is hard-fought (you could say Darwinian), an arena of competing forces fighting for survival in an post-industrial landscape.

Central to The Kid with a Bike is the problem of scarcity — economic scarcity, the scarcity of love smothered-out by self-interest — and the movie’s conflicts are rooted in the resulting cruelty as the scattered, wanting protagonists jockey for survival. However harsh the Dardenne’s vision, there is something beautiful, almost soothing, about its honesty, a base depiction of human behavior that eschews ideals, and by doing so, presents a vision of kindness and love whose presence is all the more gratifying.

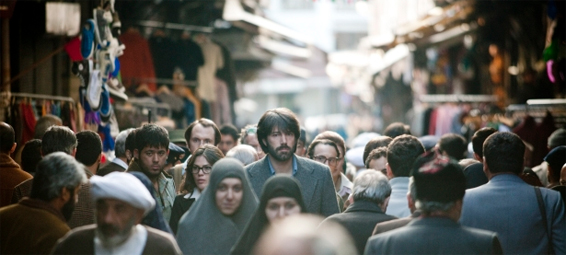

6. Argo (Dir. Ben Affleck)

I’d be hard-pressed to name another film this year for which I enjoyed the experience of watching it more thoroughly than Argo. Ben Affleck’s third film is accessible and exciting, keenly conscious of the implications of its drama, well-acted, historically and politically pertinent, funny, self-effacing, and buoyant. And while Argo is essentially about the kind of daring, self-denying courage that our heroes are capable of, it also orchestrates a vision of grand global theatrics. The movie uses its Hollywood-in-Iran storyline not merely to produce amusing and often hilarious situations, but to pull the curtain back on an unseen world that drives geo-politics. And in the midst of all the hard difficulties of the world, sometimes it is just downright reassuring to know that there are good guys like Affleck’s Tony Mendez out there, behind the scenes with their sleeves rolled up, trying to make sure that everything turns out okay.

7. The Deep Blue Sea (Dir. Terence Davies)

British director Terence Davies’ first feature film in eleven years, The Deep Blue Sea doesn’t quite reach the same level of exquisite, elegiac nostalgia that characterized his greatest films, Distant Voices, Still Lives and The Long Day Closes, but this movie does manage to bring together a compelling mix of social melodrama and a deep-feeling emotionality. Rachel Weisz turns in a quiet, moving performance, but it is Davies’ effortless touch that is the star here, creating an exquisitely-paced, richly-textured, and long-lasting story about a woman with a capacity for love that is at odds with the social mores of her historical moment.

8. The Turin Horse (Dir. Bela Tarr)

The eccentric and notorious Hungarian filmmaker Bela Tarr is the closest we will come to understating what Vermeer or Bruegel might have done with a movie camera. What makes his films so fascinating and seemingly from another age is that they operate with an entirely other understanding of time and space. In The Turin Horse, which screened at this year’s Oak Cliff Film Festival, we have peasant life bluntly realized, with excruciatingly long takes depicting the simplest actions – the eating of gruel, the lighting of a candle. As we challenge our own patience to withstand the monotony of the film, exterior ruminations settle in. This is how most of humanity existed for most of time. These characters’ existence is so slim, yet what is essentially human about them is still starkly present. Tarr’s character sits and stares out the window; we are like those sitting outside the cave, looking back in at the shadow play (or is it the other way around?).

The Turin Horse presents a struggle of needs and resources, a sick horse, the blistering elements, nature, hunger, and murder as an ever-present existential threat. That the movie feels other-worldly should give us pause. It is a story of a planet ever-rejecting its inhabitants, and one that, as mega-storms drown our cities and shipping liners navigate the melting ice caps, would do us good to remember. Despite our seeming distance, it is a story that is still ours.

9. The Master (Dir. Paul Thomas Anderson)

I have a love/hate relationship with Paul Thomas Anderson’s baffling and enigmatic cult film. On the one hand, it is driven by some of the year’s most dynamic and unforgettable performances, and drenched in a style that is as beautiful as it is baffling. But what is The Master trying to say? After multiple viewings and many conversations, The Master proved a film that could be picked apart, interpreted and deciphered in so many ways it was as if the movie itself was merely a sponge ready to sop up a multitude of projected meanings I believe this is because Anderson is an immensely gifted and intuitive filmmaker. His film is held together by a visual and stylistic logic that allows its narrative coherence to evaporate without losing our attention. However ultimately unsatisfying, it is hard not to stand in awe of that accomplishment. In fact, it makes The Master a strange kind of movie, one whose own failings still have so much to show us about the nature of cinematic language.

10. Alps (Giorgos Lanhimos)

Giorgos Lanhimos’ latest bizarre tale about a team of surrogates hired to stand-in and role-play the lives of their clients’ deceased loved ones isn’t as crisp, defiant, or undeniable as his previous film, the Oscar-nominated Dogtooth. But there fewer more compelling, original, or urgent directors working in the movies today. Defined by a style that is as alienating as the vacant worlds he creates, Lanhimos can make the unthinkable and the most eccentric kind of bizarreness feel ubiquitous or mundane. Trauma is not only Alps‘s subject, a kind of traumatic narrative disconnect gives the film its shape. It is this stilted-shaken form that allows the film probe idiosyncrasies of modern love, existential suffering, and social alienation with surprising and disarming nuance.

11. Barbara (Opens in Dallas on Dec 21)

12. Beasts of the Southern Wild

13. Django Unchained (Opens in Dallas on 25)

14. Cosmopolis

15. Rust and Bone (Opens in Dallas on Dec 21)

16. Footnote

17. Elena

18. Monsieur Lazhar

19. Bullhead

21. Take This Waltz

22. Moonrise Kingdom

24. Bernie