I grew up in a family that cherished old things. My parents were avid Early American antique collectors. We spent many vacations in Williamsburg, Virginia, where my brother and I were dragged through Colonial-style homes and hundreds of antique shops. When they built a true-to-form Williamsburg Colonial home in North Dallas, they filled it with expensive, authentic antique furniture and decorative items.

After my mother passed away, my brother, sister, and I began the arduous task of dividing and selling our parents’ sacred artifacts. We learned a hard lesson: Everything old is not necessarily new again. I called several local antique stores for help figuring out how much our furniture was worth. Only one returned my call, and when the owner showed up at my house to see it, he looked around and said, “Well, you didn’t tell me you were talking about Early American antiques. Nobody in Dallas is interested in these.”

“There are a lot of people who have invested in furniture, gemstones, or art only to find out their investment doesn’t always hold up over time,” says Beverly Morris, a certified appraiser of personal property in Dallas. “The reality is that young people don’t want old things right now.”

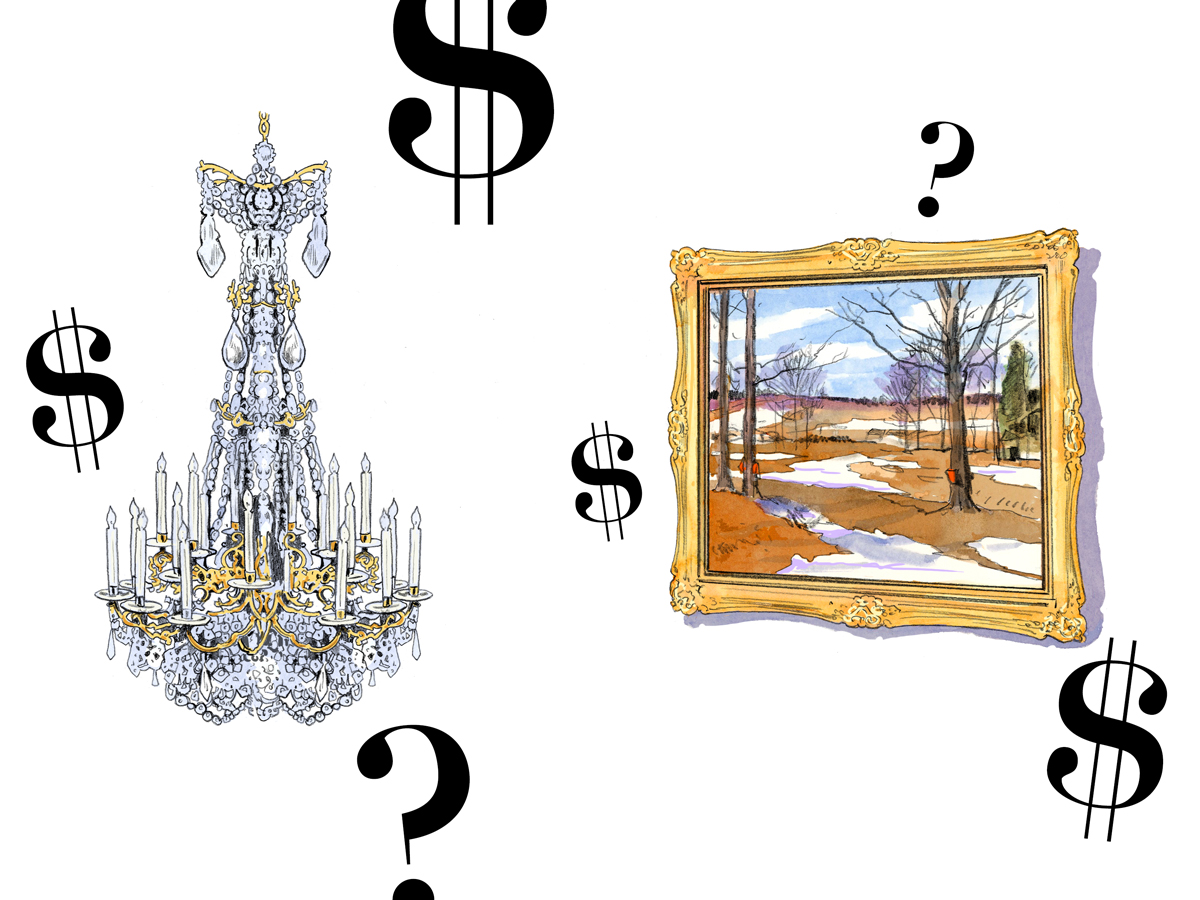

My aunt learned that lesson the hard way. In 2005, her stunning 24-lamp Louis XVI Baccarat chandelier was appraised for $60,000. Every Thanksgiving we’d sit around her fancy French oak dining table, under the soft lights twinkling off of the crystal pendants, and listen to my cousin brag about what he was going to buy with that $60,000. Today, I can’t find an auction house to even look at it.

“There are many similar chandeliers coming on the market,” says Karen Rigdon, director of decorative arts and design, silver, and vertu at Heritage Auctions, in an email. “As a result, the secondary market is saturated and auction results are poor. We will not be able to assist with its sale.” She referred me to Thomas Grant Chandeliers, a dealer in the Design District who has been in the custom lighting industry for 50 years. Unfortunately, they confirmed what I’d been told by Rigdon and said the demand for fine lighting was so down that they were going to close shop.

I decided to turn to the Internet and do my own research. This endeavor proved time-consuming. You have to weed through the “experts” and make a lot of phone calls before you can get a sense of what your items are really worth. Ebay and Craigslist are shaky sources unless you are able to access the sold prices, but eventually I found several websites that helped me get a ballpark estimate of what my items were worth. I learned that once something goes out of style, it takes between 25 to 30 years for it to come back again. If you have time to wait it out, you might be better off holding onto it.

“The downturn in the economy in 2008 caused a big change in the antique business,” says Jerry Holley, executive vice president of Dallas Auction Gallery. “Some areas have disappeared and I don’t know if they will ever come back. Young people don’t want ‘grandmother things’ like cut or pressed glass or big brown furniture. If you like it, keep it. If not, get what you can for it and walk away.”

I hoped I’d have better luck with an oil painting I’d inherited. My grandfather was a collector of fine American art, mostly artists in the Northeast where he grew up. When he passed away, my father inherited a painting by noted snowscape artist Aldro Hibbard. The peaceful, snowy Vermont landscape with red sugar maple tins hanging from the trees was the centerpiece of our living room. My father used to say, “Hang onto this painting, it’s going to be worth a fortune.”

I sent a picture of the Hibbard painting to Heritage Auctions in 2012 and asked them to consider auctioning it. Their advice was to contact a gallery in the Northeast, where it might sell for $5,000. I gave up on the project.

In early December 2015, I decided to try and sell the painting again. This time, I bought a one-month membership to askart.com for $30. The site allowed me to search artists, view recent and upcoming sales, and sign up for an alert for any new works that sell or became available. I studied 647 transactions for Aldro Hibbard and also found a list of galleries with an interest in Hibbard’s work. I sent photographs and measurements to all of them. I spent hours on the phone with collectors familiar with Hibbard and learned that most of the people who collect his works live in the Northeast, so I should concentrate on galleries in Vermont and Massachusetts. But now, as an educated seller, it was easier to approach a gallery or an auction house and demand a higher price.

It’s exhausting work to be sure. Every gallery and auction house has a different perspective on your piece as well as different commission structures. Some dealers will buy your painting and mark it up to sell. Others might offer you a price and then subtract a commission that could range from 20 to 40 percent. Auction houses usually have set guidelines: The seller pays a small fee, while the buyer is charged up to 20 percent (or more) of the hammer price. But I stayed with it and after a couple of months of negotiating, I’m close to making a deal that my father would approve.

Donald King Cowan, an accredited appraiser in Dallas, recommends getting a certified appraisal for high-dollar items. “First, people have to identify what they have and what they want to do with it,” says Cowan. “We can’t always go on a photograph. We need to see it, feel it, and touch it, especially if the appraisal is for insurance purposes or a charity donation.”

If you have a houseful of items and want a quick sale, your best bet is to call an estate sale company and make reservations for a nice dinner at The French Room. There, you can be surrounded by antiques and not have to worry about how much they are worth.