As bombs, missiles, and rockets exploded around his village in south Lebanon, a young Mark Haidar and his friends cheered while playing in the street.

“As kids, we would say, ‘If you hear it, that means you’re not dead,’” Haidar recalls. “We started cheering every time we heard an explosion. We were not cheering for the explosion; we were cheering because we were alive.”

The co-founder and chairman of Dallas-based tech company Dialexa and co-founder and CEO of automotive fleet management software firm Vinli grew up fighting to survive the war and poverty that surrounded him. Now, Haidar channels the same drive, spirit, sacrifice, and strategic thinking to lead his two companies. “Honestly,” he says, “these companies were defined by the hard moments. Company culture is not created during good times. Company culture is defined during hard times.”

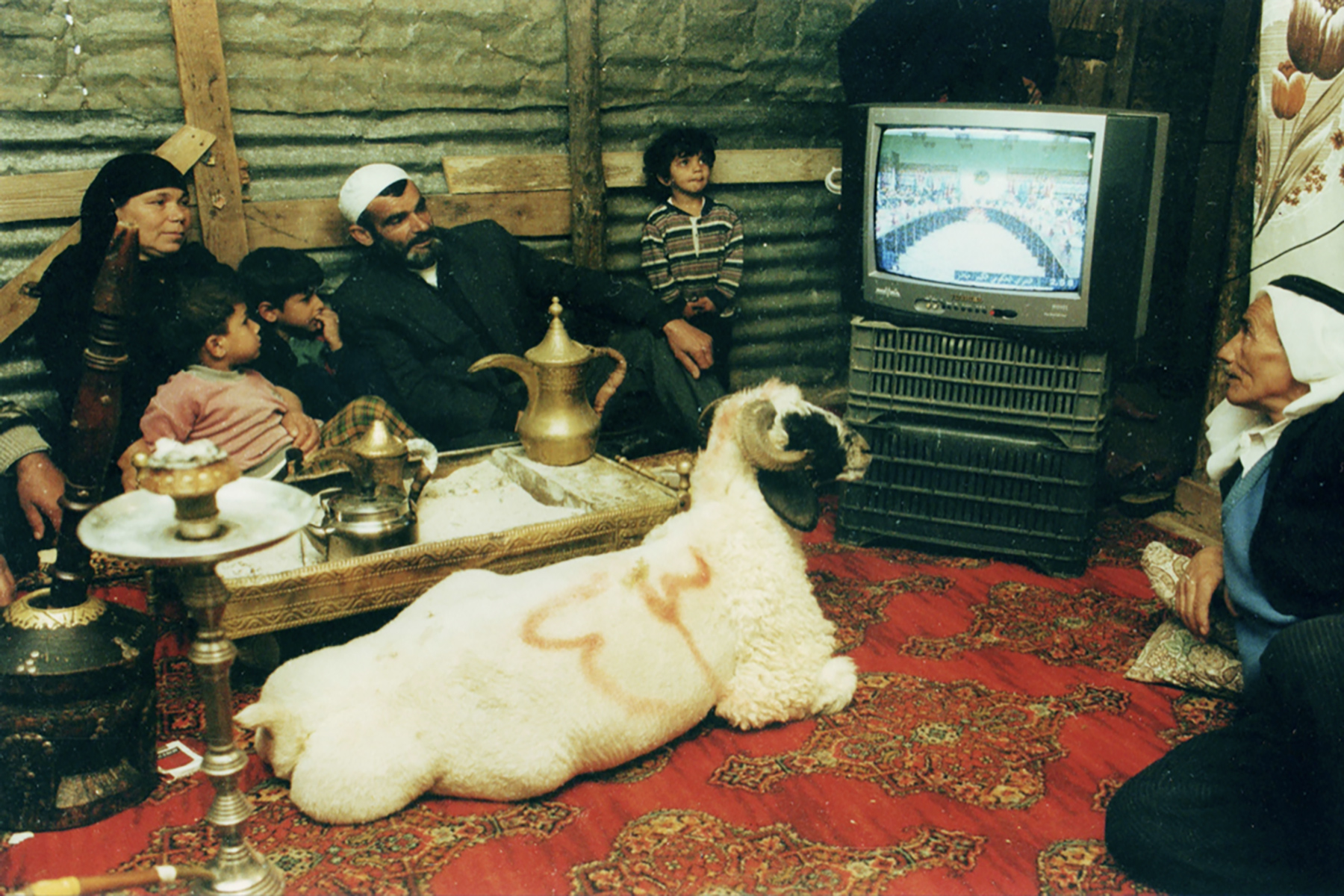

Haidar knows a thing or two about hard times. During Lebanese wars in the 1980s, his village was destroyed, and he and his family were forced to move to a refugee area near Sidon. “Our place was a living room in an apartment shared by other family members,” Haidar recalls. The family converted a balcony into their kitchen and bathroom. There was no plumbing, electricity was available only four hours per day, and food was scarce. Often, they had just one meal per day.

To get to school, Haidar would cram into the back of an old Volkswagen van—which a neighbor had converted into a makeshift bus with 30 miniature seats—and ride through streets lined with Syrian soldiers. “The schools didn’t have resources,” Haidar says. Lessons covered only basic spelling and math. Still, Haidar discovered an early interest in technology.

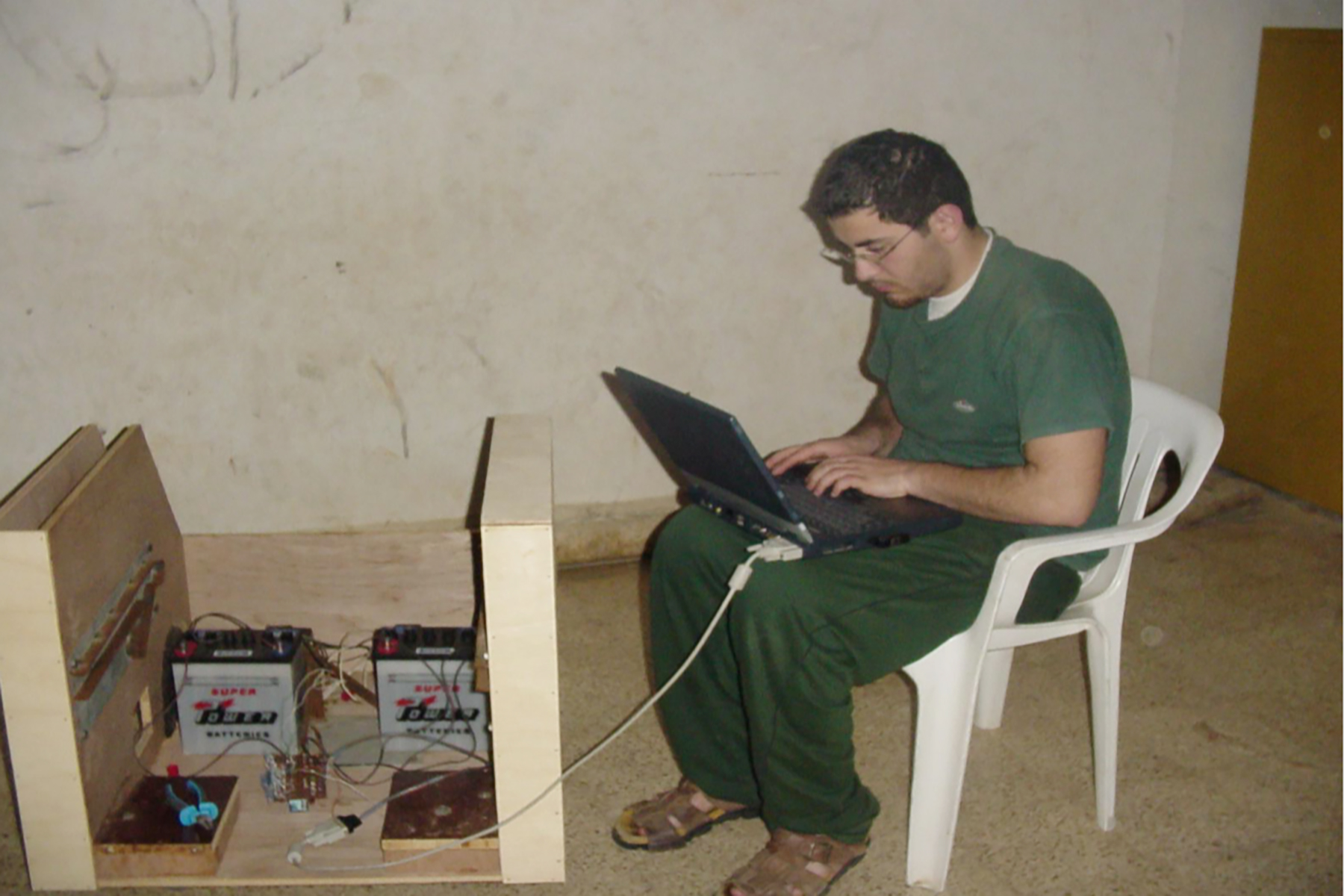

UNICEF donated two computers and operating system manuals to Haidar’s school, and he became enthralled with programming. “For the first time in my life, I felt that I had one thing I could control—which was that computer,” he says. “You tell the computer what to do, and it’ll do it for you. That was so empowering.”

By 14, Haidar had outgrown the two coding books he had been reading during recess. So, on weekends, he began taking public transport to the library in Beirut to copy pages from programming books he could not afford to buy. “It was great for me because as I’m copying, I’m almost reading and learning,” he says. Later, he would return to school and practice implementing the new code.

This passion for programming led Haidar to Beirut Arab University. To fund his education, he started his first company—a contract coding and engineering business. “The mission statement of that company was to make $4,000 a year, which was the school’s tuition,” Haidar recounts. His first project was creating a smart chair to give mobility to those who lost limbs during the war. He went on to earn money by converting Lebanese government records from print to digital and creating the university’s credit management system.

Charming ‘Lisa No Visa’

After earning his undergraduate degree, Haidar was determined to continue his education in the U.S. “I felt I didn’t have a life, and I didn’t have liberty, and I was not allowed to pursue happiness, and I thought, ‘Oh, my God, I can go to a place where these are my rights?!’” he says. He was accepted to a graduate engineering program at the University of Detroit Mercy, and a family member, who Haidar describes as “the richest man in the region,” with $37,000 in his bank account, agreed to provide a financial statement to the U.S. embassy and essentially cosign for Haidar’s tuition.

When it was time for his immigration interview, Haidar was worried. “The visa officer was an urban legend in Lebanon. People called her ‘Lisa No Visa,’” he laughs, recalling the nerves he had watching people exit the immigration office defeated. When his turn came, the female officer asked preliminary questions about his planned journey and then asked how he had managed to learn English so well. “I told her, ‘I memorized the two best documentaries about America,’” Haidar says. She asked which ones. “I said, ‘Seinfeld and The Simpsons,’ and she cracked up,” he says, smiling at the memory. He received a stamp on his passport a few days later.

As Haidar prepared to move, Lebanese Shiite terrorist group Hezbollah attacked Israel, sparking the 2006 Lebanon War. “The bombing was within a one-mile radius of us,” Haidar says. Infrastructure shut down as ships bombed cars driving on highways, F-16s took out bridges, and families crowded into ground-floor apartments—such as Haidar’s—for protection. “We thought we were going to die,” he says.

Between blasts, his father approached him with a bold proposition. Haidar chokes up recounting his father’s words: “He said: ‘I prepared a surprise for you. I have been saving this money all my life, and I’ve got a credit card. I’ve saved $2,300. Leave $300 and flee the country. You’re the only one who has a shot to survive.’” Initially, Haidar refused to take his father’s life savings and leave his family for dead, but his father insisted, saying either Haidar would die with them or take a chance at survival. Haidar decided to follow his father’s wishes.

As it turns out, one of the family’s neighbors was an oil smuggler. Haidar climbed into his neighbor’s truck to sneak to the Syrian border, quickly saying goodbye to his father. “I couldn’t see my mom because it was really rushed,” he recalls. Later, he learned she had fainted, and the family had hidden her from him so he would not change his mind.

Once near Syria, Haidar took a taxi to Damascus and began searching for a flight to America. “The problem was that everyone was fleeing Lebanon from all around the world,” he recalls. Tourists who had taken untimely vacations to Lebanon were escaping through Damascus, skyrocketing flight prices to between $2,000 and $3,000 for a one-way ticket. After paying the smuggler and the taxi driver, Haidar had just $1,900.

To conserve cash, he began sleeping in the streets and skipping meals while he planned his next move. A travel agent suggested he depart from Istanbul, so he bought a $30 bus ticket and braved a 40-hour ride into Turkey. Typically, Lebanese citizens must procure a visa in Lebanon prior to entering Turkey. For Haidar, this would be impossible. “I went to the Turkish consulate, I slept outside, and then, when it opened in the morning, I was there,” he says. He showed the consulate his dad’s savings and his U.S. visa, and the government granted him five days to find a plane ticket and get out.

He traveled to several cities searching for a ticket he could afford, with no luck. After 6 days without food and 15 without a shower, frustrated as time ran down, Haidar entered a hotel and explained his situation to the owner. “This lady gave me the top suite in the hotel and free breakfast for $30,” Haidar says. He bathed, ate, and called his family, dropping to his knees when his sister answered the phone in high spirits. Next, he called the travel agent, who told him he had found a ticket for $500—but it was for New York, not Detroit. Beyond relieved, Haidar replied, “I don’t care if you throw me over the Atlantic Ocean and I have to swim to America.”

American Ambition

Once he finally stepped off the Greyhound that had brought him from New York to Detroit, Haidar had a new problem to solve. “I had to figure out how to pay $30,000 a year in tuition,” he says. His cousin told him about a night shift opening at a gas station in a dangerous neighborhood where he thought Haidar could get hired. It turned out to be the hardest job interview Haidar had experienced. “Everything was so different,” he says. “There are computers connected to pumps. And what is a Reese’s Peanut Butter Cup? I’ve never seen a Reese’s Peanut Butter Cup. 20 ounces? What is an ounce? It just was so overwhelming.”

Haidar memorized SKU numbers to get the job, working the 7 p.m. to 7 a.m. shift for $8.50 per hour. This, he thought, would cover his basic living expenses.

He pitched a deal to the university to supplement his income: if he helped its robotics program successfully apply for U.S. military grants, they would make Haidar the project’s lead researcher and wave his tuition. The school got the grant, and Haidar began working on sensors that could predict when military vehicles would break down. “There was a big problem with the Humvees breaking in the middle of Iraq,” he remembers. “That was kind of the inception of it.”

He slept from about 2 p.m. to 6 p.m. each day, around his job, research, and classes. “I got this alarm that truck drivers use,” he says. “That thing could wake up an elephant.” Haidar graduated two years later, debt-free and with $20,000 in savings, even after sending $100 to his family in Lebanon each week.

He moved to Dallas post-grad to chase a relationship that ultimately didn’t last, falling in love with the Lone Star State instead. “I tell people, ‘Texas is the biggest hidden secret in America,’” Haidar says. He was hired as chief technology officer at Plano-based startup 2Go Software Solutions in 2009, where he met Scott Harper, the company’s vice president of operations. The two were immediately thrown into the chaotic trenches of startup life and created a brotherly bond (see sidebar). “We were out grinding and working what I think most people would consider an unpalatable amount,” Harper recalls. They worked together for nearly a year before leaving 2Go over disagreements with company leadership. “We quit the same day,” Haidar says. “And the next day, we started Dialexa.”

Exploring Possibilities

Dallas-based Dialexa was born when Haidar and Harper each pitched in $25 to meet the $50 minimum requirement to open a business account at Bank of America. The duo performed tech consulting to pay the bills and discovered there was a market gap for services helping companies transition their operations to digital. “We wanted to enable these companies that are not digitally native to build their own products and transform,” Haidar says. He and Harper formally launched Dialexa in 2010 under this new model as co-CEOs.

Five years later, the duo created an incubator within Dialexa. Its first venture was Vinli, an automotive fleet management software company that originally provided a platform for the development of in-car apps and data tracking. “We wanted to be the Apple TV for the car,” Haidar says. It was backed by $6.5 million in funding from Samsung, Cox Automotive, Continental, and other giants.

Intrigued by the possibilities, Haidar decided to step into a chairman role at Dialexa and lead Vinli full-time as co-founder and CEO. “I’m passionate about the automotive space in general because the whole automotive space is about to change completely with electrification, autonomy, and connectivity,” he says. “I saw that as a very exciting opportunity for me to pursue.”

In its first 10 months, Vinli became the largest app ecosystem in the automotive industry, offering 53 apps through its marketplace. But when automakers began creating connected cars, the company was forced to change course. “We became more of a B2B model, where we license our technology to large fleets, insurance companies, and automakers,” Haidar says. Today, Vinli enables the largest automotive fleet in the world—3.5 million cars operated by French company ALD Automotive—providing fleet management, data intelligence, and usage-based insurance solutions.

More recently, it has tapped into risk management. “Think of it as kind of the FICO score for mobility,” Haidar says. This new layer of software helps insurance companies predict how many claims they might have and the claims’ cost. A third layer of Vinli’s software uses data to create predictive models for their automotive clients: much like when Haidar helped the military predict when its vehicles would break, he can now do similar things for large fleets of commercial automotives.

“Having a knowledge company that’s able to manage that technology with the car manufacturers, fleet operators, and chip companies is quite unique,” says Ken Hersh, co-founder and former CEO of NGP Energy Capital Management, president and CEO of the George W. Bush Presidential Center, and a Series B investor in Vinli. “Mark, as a leader, has my confidence.”

While continuing to build Vinli, Haidar will begin leading two nonprofits next year. The first will be a space and solar observatory in West Texas that provides children in underserved areas with access to space exploration. Tapping into Haidar’s roots, the second will be a nonprofit called Remember My Name, which will share 60-second videos of children in high-conflict areas to help viewers see them as more than victims of war or conflict. “If you humanize [them], people will have a very different reaction,” Haidar says.

He has been back to Lebanon after his escape in 2006. But these days, taking his two children to see their paternal grandparents is a little easier as his parents moved to Richardson about a year ago. He’s grateful that his path ultimately led him to the Lone Star State. “I tell people I wasn’t born American, but I’ve always been Texan,” Haidar says.

Brotherly Bond

Dialexa co-founders Mark Haidar and Scott Harper have never let cultural differences divide them. “Even though we grew up thousands of miles away, with different environments, different countries, different cultures, different religions, different everything, we couldn’t be more similar,” Haidar says. Harper was raised in small-town Arkansas and had little exposure to anyone from the Middle East prior to meeting Haidar, but from the start, the two have been open, sparking conversations that led to understanding and trust. “A lot of that type of dialogue was an educating experience for both of us and eye-opening,” Harper says. Both have hosted each other on trips to their respective family homes, with Harper venturing to Lebanon and Haidar experiencing a Razorbacks game in Arkansas. Despite he and Haidar both being what Harper calls “mega, extreme Type A personalities” he says in all their endeavors, they have never fought. “Neither one of us care about being right,” he says. “We care about getting to the right answer, and that’s why our partnership works so well.”

Taking Flight

Mark Haidar has had a passion for flying ever since he was a child, looking up at the bellies of F-16 fighter jets breaking the sound barrier. “It was scary, but fascinating to see,” he says. His aspiration of pursuing a pilot’s license became a reality in 2018, shortly after marrying his wife, Claire, who had a similar dream growing up in South Africa. “She wanted to join the Air Force,” Haidar says. The couple began taking flying lessons during the pandemic and Haidar quickly became obsessed. “I got my private pilot’s license, and then I got my instruments, and I got my commercial rating, and then I got my jet rating,” he says. Now, Haidar spends weekends flying his family all over the world and is working on a license to fly experimental planes. Claire, who was delayed in her pilot pursuit by a recent pregnancy, will soon join him in the cockpit. “We are getting to explore and go places that are so remote and be able to do it all together as a family,” Haidar says.

Author