In 1974, Shu-Chang “Buck” Kao opened Royal China in the Preston Royal shopping center. Buck was a retired Taiwanese diplomat from Hunan and a veteran of World War II. A chef from Taiwan joined him in the kitchen to help serve Mandarin, Sichuan, and Shanghainese dishes in Dallas, and Buck quickly became beloved by the community.

Today, Royal China is known for its hand-pulled noodles and xiao long bao. It’s also the longest-running family-owned Chinese restaurant in Dallas, after being passed on to Buck’s son and daughter-in-law, George and April Kao.

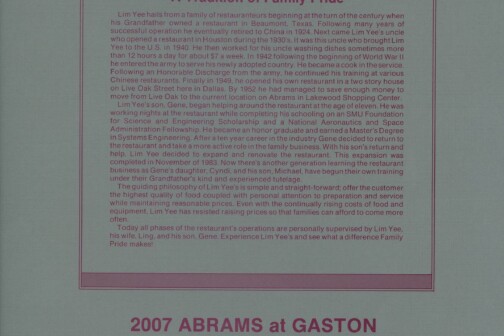

The history of Royal China and several other Chinese restaurants in Dallas are being showcased in a new exhibit by the Dallas Asian American Historical Society, a nonprofit that launched in 2022 to record and preserve the history of these communities in North Texas. The show is being hosted by Preservation Dallas and will be on display inside the Wilson House through mid-September.

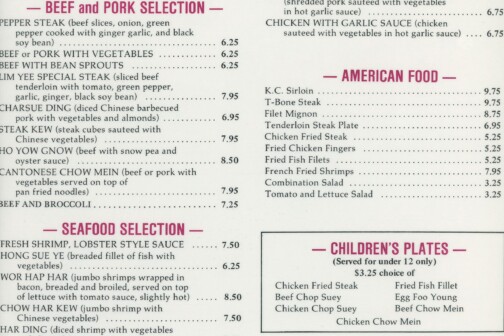

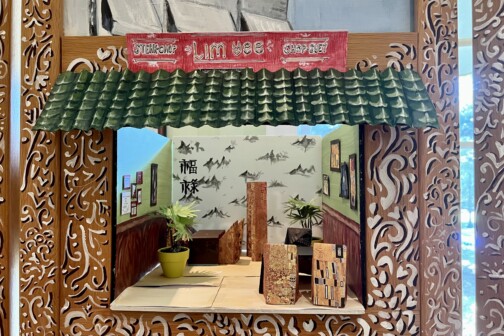

Stephanie Drenka and Denise Johnson, the co-founders of the Dallas Asian American Historical Society, made it their mission to pursue the project after coming across a matchbook on eBay from a restaurant called the China Clipper Café. They’ve since hunted down more matchbooks, menus, and historic photos from long-gone eateries like August Moon, Ming Garden, and Lim Yee Restaurant.

“Upon closer examination, you see addresses that are in the heart of Dallas,” says Christina Hahn, the exhibit’s creative director. “That got them thinking, ‘Oh my gosh, have we been here for that much longer?’”

The Exhibit’s Artifacts

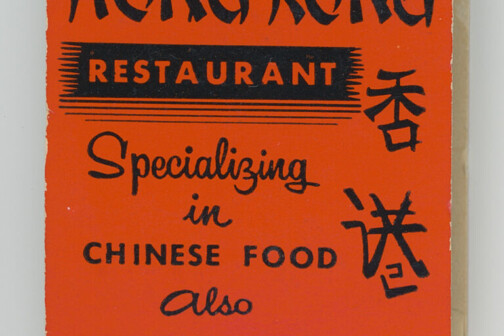

Chef Bill Pon (foreground) in the kitchen of Hong Kong Restaurant.

Courtesy of Dallas Asian American Historical Society

“Hunan Restaurant opened in 1976 according to Dallas Morning News‘ archives,” Drenka says. “This wasn’t one of the restaurants whose family we found, but it was located on Greenville Avenue at Lovers Lane.” Hunan Restaurant closed its doors after 25 years in 2001 to make room for H-E-B’s Central Market grocery store.

Courtesy of Dallas Asian American Historical Society

“We didn’t interview the family of Ming Garden either,” Drenka says. “It was started by Wayne Yee and eventually expanded into multiple locations. The first was at Preston Forest. They were known for the fresh buffet style food.”

Courtesy of Dallas Asian American Historical Society

Drenka says the Hong Kong matchbook was provided by Justin Pon, grandson of Chef Bill Pon.

Courtesy of Dallas Asian American Historical Society

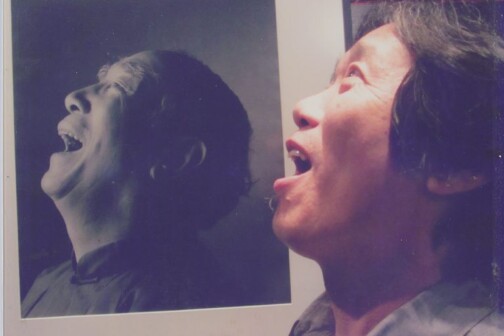

“The photo from Royal China is George Kao, current owner of the restaurant and son of the founder Buck Kao, posing in front of a photo of his father,” Drenka says. “Royal China will celebrate its 50th anniversary next year and is the oldest single-family-owned continuously operating Chinese restaurant in Dallas.”

Courtesy of Dallas Asian American Historical Society

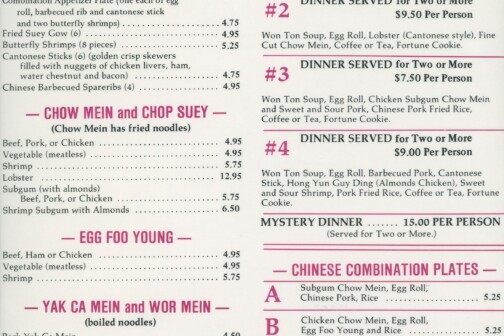

The front of the menu of Lim Yee. “We received the menu from Michael Yee, grandson of Lim Yee, who reached out to us after reading the Dallas Morning News article,” Drenka says. “He has been so kind in finding artifacts for us to showcase and even brought donuts for our high school art students.”

Courtesy of Dallas Asian American Historical SocietyDrenka and Johnson spent the better part of a year scouring the Dallas Morning News’ archives and interviewing family members to learn more about the city’s history of Chinese restaurants and the people responsible for them. The two learned the city’s first documented person of Chinese descent in Dallas was in 1873, the same year the city put out its first directory.

Chinese immigrants came to the city in the 1870s by way of the railroad system that connected Houston to Dallas, Drenka says. They arrived in the U.S. years prior during the California Gold Rush in the 1850s. They found domestic work at laundromats and then at restaurants. In 1896, Jim Wing purchased Moon Restaurant, making his mark as the first documented Chinese restaurateur in Dallas.

The timeline of Chinese American growth is displayed in the conference room of the Wilson House on a tapestry painted by hand in a traditional Chinese style by some of the Historical Society’s interns. The events are tied together with a red rope that’s been twisted and tied through Chinese cord knots.

“If you stand on the other side [of the room], you can take it all in at once,” Hahn says. “It’s quite overwhelming.”

Most Asian American artifacts are retained in private collections in family homes because there are no buildings that have been preserved. The matchbooks, photos, and old menus were proof that a history existed.

Families began to reach out to Drenka and Johnson after the Dallas Morning News first reported their documenting efforts. They came forward with stories and photos of their ancestors who folded dumplings and worked in steamy kitchens. Many families were surprised that Drenka and Johnson took a keen interest in these stories.

Justin Pon is the grandson of Bill Pon, who opened Hong Kong Restaurant on Garland Road in 1962, and later, Chef Pon’s Oriental Cafeteria. Bill came to the U.S. when he was 14 years old to work at a laundromat in Oakland, California, before he arrived in Dallas. Drenka conducted an interview with Justin and his father, Bill Pon Jr., via Zoom shortly before Bill Jr. passed away.

“[Justin] said, ‘I want you to know that my father told me how happy he was that you guys were doing this work and how honored he was that you were featuring our family,’” Drenka says. “It really reaffirmed how important and necessary this work is.”

The elder Bill’s cleaver, whose blade is etched with Chinese symbols, is encased in an acrylic box as part of the exhibit.

Another Taste of the Exhibit

Drenka and Hahn estimate that the exhibit is only about 10 to 20 percent of what they have collected. Most photos are digitized and hosted on the Dallas Asian American Historical Society website, along with scans of the menus and matchbooks.

The exhibit spans three rooms, a hallway, and part of the house’s staircase. There are artifacts, poster boards, and displays of the Historical Society’s findings, which include oral histories of family members. A room in the house has a table with replicas of dishes that would have been served at some of the restaurants, including Peking duck, egg rolls, and rice cakes.

A menu from Chan’s Chinese Cottage—which was located at 4830 Greenville Ave., now the location of a CareNow clinic—features chow mein, jumbo shrimp, and Chinese winter melon soup.

The restaurant relocated from Haskell and Fitzhugh in the late 1950s, when it was initially called The Chinese Cottage. It made such a mark on doctors at the nearby Baylor University Medical Center that they recommended it to their patients because there were so many vegetables on the menu, Drenka says. The restaurant also served a “mystery dinner,” which meant chef Wah Chun would cook up a surprise meal for his guests. Many of his customers were loyal, so Chun often knew exactly what they liked.

In one room toward the back of the house, a map with an acrylic overlay has a dozen markers designating where a Chinese restaurant is or was once located. One teetered near White Rock Lake. Two were by Love Field Airport. Three were in downtown Dallas.

“This was intentional to show that Asian people aren’t just up in the suburbs,” Hahn says. “They have been in the heart of Dallas, serving other Dallasites, and they’ve been here for a very long time.”

“Leftover: The Enduring Legacy of Chinese Cuisine in Dallas,” will be open for public viewing Friday, July 7, and Saturday, July 8, at Wilson House on the Meadows Foundation’s Wilson Block campus at 2922 Swiss Ave. Viewings after July 8th can be arranged through mid-September by appointment by contacting Preservation Dallas at 214-821-3290 or at [email protected].

Author