Don DeLillo’s 2003 novella, Cosmopolis, is something of a cinematic siren song, a book that begs to be adapted to the screen even if that adaption is trickier that it seems at first. Tightly constructed, deeply thought, irreverent, unabashed, relevant, and scathingly critical, it’s a story that takes place nearly entirely in a moving vehicle – and the car has to be the movie camera’s closet technological cousin (it frames the world through the windshield, panning past landscapes, moving through time). Cosmopolis is a road story, a white limo crawling through the streets of Manhattan carrying a mega-billionaire in the throws of a financial and existential crisis, and a man who desperate needs, of all things, a haircut.

But the irony of the central image of DeLillo’s book – the limo – is that while this is a story in constant motion, it is also caught in a kind of perpetual stasis. We spend most of the time inside the quiet limo, conversing about the world in a place that feels both in and out-of it, moving, but eerily still. So how do you make this book a movie? Director David Cronenberg takes an approach that fans of DeLillo will find satisfying: he stays faithful – almost piously so – to the text. It is a film that plays like a dramatization, Cronenberg delivering a restrained film that fizzles and sizzles through the sheer force of its language and ideas.

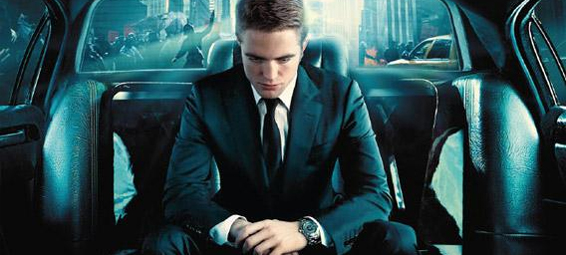

The plot is a minor character in this philosophical drama. In the film, Eric Packer (Robert Pattinson) is our limo-riding mega-billionaire who has hedged his great wealth against the yen, buying the currency cheap and then investing it in stocks, assuming that as the yen falls in value, he will make his money back and then some. Only the yen isn’t falling, prompting Eric’s crisis. The crisis, though, isn’t so much a financial one as it is a philosophic one, one that confounds the genius-investor’s ability to anticipate patterns in the market, and by extension, patterns in behavior and the natural world. It is a conflict between reason and the unexplainable, between the world of high finance – a construct created out of the rapid-fire exchange of information — and the natural dynamism of human life. Life’s rawness, this unpredictability is personified both in the protests and unrest that breakout and escalate throughout the day, swirling around the limo to Eric’s detached and speculative amusement, and in the character of Benno Levin (Paul Giamatti), a disgruntled former employee with a death wish. Or is it? Are these sideshows merely predicable entities, slag created by market mechanics?

It is tempting to get lost in all of Cosmopolis’ little details, the little references that hold so little and so much. There’s a passing conversation about Rothko Eric has with Didi Fancher (Juliette Binoche), whom he meets for sex while cruising in his limo. Eric tells Didi he wants to buy the Rothko chapel, a crass suggestion that we take, at first, as vulgar display of his vein and unchecked appetite. But later on, during a sizzling dialogue with his “chief of theory,” Vija Kinsky (Samantha Morton), the subject of painting comes up again, as the theorician compares the evolution of money into money for its own sake as akin to the loss of narrative in painting. This sets the stage for a discussion between Viga and Eric about time and its incomprehensible dissection into infinitesimal quantities – nanoseconds, yoctosecond – until science reveals that the present itself hardly exists as a measurable quantity. It’s a humorous exchange, but we can’t shake the association between this infinitesimal dissection of time and the power of the paintings in Rothko’s chapel– the way they intend to overwhelm you with the sensation of being in the present. This is how Cosmopolis works, literature in kind with the world it describes – metaphors, analogies, allusions, syntax, language, and ideas, all flickering past you like the marker ticker on the screens in Eric’s limo.

This all makes for a film that is exceedingly difficult, perhaps even more than the book because of its pace, but also a movie that is exciting in part because it is a rare for a film released in 2012 to have this much respect for the intelligence of its audience. Pattinson is also a force, slithering and wire-tight, yet smoothly affecting and always in control. If you wrote this guy off because of Twilight, think again. He can act his pants off – and with his pants off, as in one of the film’s wickedly funny dialogues that takes place during an in-limo prostate exam.

Cosmopolis feels more pertinent a story today – after the financial collapse — than it was when first released. The book makes DeLillo look prophetic, both his registering of the fracturing strain of economic forces at play in the world, and for seeing that there is something irreversible about the escalation of the power of the market, globalization, and massive wealth — that even after crisis, the world continues to spin on in Cosmopolis’ image. The underlying implication is that the market, the way information is exchanged, the rapid dissociation and abstraction of contemporary life has fundamentally affected the nature of things — the way we think, perceive the world, and love. This is what truly disturbs about Cosmopolis, a strange and ambiguous film, a difficult and necessary confrontation.