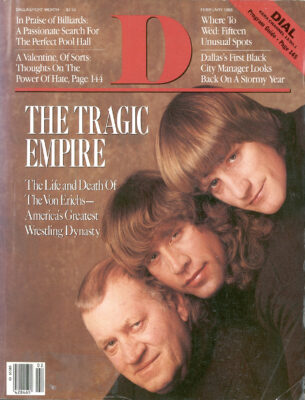

Editor’s Note: This story was first published in a different era. It may contain words or themes that today we find objectionable. We nonetheless have preserved the story in our archive, without editing, to offer a clear look at this magazine’s contribution to the historical record.

All through the autumn, the Von Erichs had been waiting for the Canadian geese to return to the little pond behind their ranch house. Fritz had bought the geese a few years ago when they were still goslings, and Chris, the youngest son, would feed them by hand. Early last spring, fully grown, they had flown off to the north. When I drove out to the Von Erich’s 500-acre East Texas spread one chilly day last fall, I saw Chris, who’s 18, out in the yard, staring at the sky. The wind had come up unexpectedly, making a hollow sound as it scurried through the pines. “He looks for the geese almost every day,” said his mother, Doris. “It’s amazing for him to believe that they will make their way back to our one little pond. But we tell him it will happen. I know you’ll think this is funny, but we consider them family. We know they’ll come back.”

All through the autumn, the Von Erichs had been waiting for the Canadian geese to return to the little pond behind their ranch house. Fritz had bought the geese a few years ago when they were still goslings, and Chris, the youngest son, would feed them by hand. Early last spring, fully grown, they had flown off to the north. When I drove out to the Von Erich’s 500-acre East Texas spread one chilly day last fall, I saw Chris, who’s 18, out in the yard, staring at the sky. The wind had come up unexpectedly, making a hollow sound as it scurried through the pines. “He looks for the geese almost every day,” said his mother, Doris. “It’s amazing for him to believe that they will make their way back to our one little pond. But we tell him it will happen. I know you’ll think this is funny, but we consider them family. We know they’ll come back.”

This was not the best time to visit the Von Erichs. A reporter from Penthouse magazine had been in Dallas the week before, asking a lot of questions about the Von Erich boys, and Fritz, who can be intimidating enough even when he’s calm, was in an uproar. From a far corner of the mansion, I could hear him booming into a telephone, his gravelly voice reverberating down the hallway like the sound of a freight train. “They’re not going to do this to us, damn it, do you hear me?” Fritz yelled into the receiver. “We’re not going to be written about like trash!”

The Penthouse reporter had been asking about the dark side of the Von Erich life. He was intrigued over what he called the “mystery” of one of the Von Erich sons, David, who was found dead in a hotel room in Japan. He wanted to know the “real” story about the suicide last spring of another son, Mike. “Don’t tell him a thing!” bellowed Fritz to a business associate. “My family isn’t going to be in a damn pornographic magazine!”

Such confrontations certainly weren’t new to Fritz Von Erich. For most of his professional life, he had been dealing with people who considered his family, at best, a garish curiosity. They were repulsed by the bombast and theatrics of wrestling; they thought it was all a scam, and surely, they figured, the Von Erichs were little more than actors who blurred the line between sport and showmanship. There was something about their lives that seemed so contrived, like a cartoon.

Yet there was also something else about them that one could not quite ignore. Astonishingly, they had become one of the legendary families of Dallas. Even those who cared nothing for the ribald netherworld of wrestling would find themselves fascinated, in a strange, almost morbid way, by the lives of the Von Erichs. Here they would come, the virtuous family in tight wrestling shorts, storming into the ring to battle their evil opponents. They would survive all the low blows, the metal folding chairs slammed over their heads when they were not watching. But then, as soon as the match was over, they would return to a reality that was littered with suffering. Since 1984, two of the six sons have died (another son, Jackie, was killed when he was 7 years old). Then Kerry, who was on his way to becoming perhaps the world’s most famous wrestling superstar, nearly lost his foot last year when he collided with a police car in a motorcycle accident. And last May, the oldest son, Kevin, came close to critically injuring himself in a match when his head was accidentally driven into a steel post. Melodrama, larger and more stunning than any illusion that can be created in a wrestling ring, has haunted the Von Erichs like a ghost.

When I began to spend time with the Von Erichs last fall, it seemed that their dynasty was coming to an end. For hundreds of thousands of wrestling fans, this mortal, all-too-imperfect clan was the last of a breed, the kind of people one used to see on old television westerns like Bonanza: plain country folk who, despite adversity, heroically stuck together and survived. The Von Erichs mattered; they were larger than life. A trip to see them was like the trip others made on Sunday mornings to church; though the people there were never certain they believed all that they saw, they felt reassured by a ritual in which the good guy, in the end, always wins.

Many wrestling observers, however, wondered just how much longer the Von Erichs could carry on. For the first time, rival wrestling promoters were coming into Dallas to lure away the prized Von Erich audience. Some openly declared war on Fritz and his sons, saying it was time for a new wrestling promotion to take over. Though I have never been sure how seriously to take the Von Erichs, as they struggled to save their name, I could not help but be intrigued, and perplexed, by their tragicomic saga, their rise and fall — and the suggestion of some larger myth that seemed to float on the fringes of their lives.

• • •

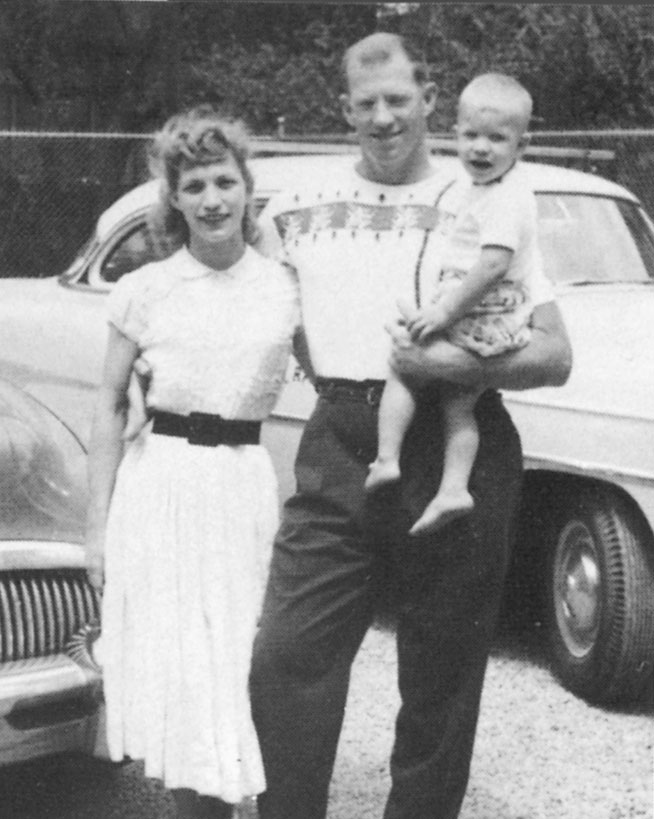

The Von Erich home, as big as a Ramada Inn, holds few mementos of the family’s wrestling legacy. Year by year, Doris Von Erich has taken down the pictures and posters. It is not that the memories are too painful; she simply wants her home to be the one last citadel of the old family she once knew. Long before Doris was a Von Erich, she was an Adkisson. The man who is now Fritz Von Erich was named Jack Adkisson, a football star at SMU who briefly played for the old Dallas Texans of the National Football League. When they married 37 years ago, they planned to quietly raise a family. Jack, a raw behemoth of a man, wanted to move to Corpus Christi to open a bait stand. But in the early ’50s, he began wrestling in Dallas at the Sportatorium: to attract attention, he began to call himself Fritz Von Erich. He adopted the role of a Nazi villain; he was a terrifying figure, and wrestling promoters throughout the country loved him. Even in the mid-’70s, when he switched roles and became a good guy in the ring, the Von Erich name remained popular, and Doris realized that her attempts to raise her sons as Adkissons — as good farm boys undazzled by the bright lights of the city and the wrestling exploits of Fritz — would be futile. The teachers at school began calling her sons “Von Erich.” She even found herself addressing her husband as Fritz. A quiet, Southern woman, the kind who was taught long ago to conceal inner turmoil behind an air of politeness, Doris told me that she still likes to be known as Doris Adkisson. “But to be honest,” she said, “we hardly know who the Adkissons are anymore. We have been a wrestling family for so long. I suppose I want the family to know that when they are tired of being Von Erichs, there is a place they can come to where they can still be Adkissons. But I don’t know” — and there was a small catch of her breath as she looked out her kitchen window — “if you can ever stop being a Von Erich.”

“The hell of it,” growled Fritz Von Erich as he suddenly loomed in the kitchen door, “is that now people watch us to see what tragedy will happen next. I wish I could explain it, but I can’t.” A scowl flapped across his famous face like sheet lightning. “We’re better known now because we die,” he said.

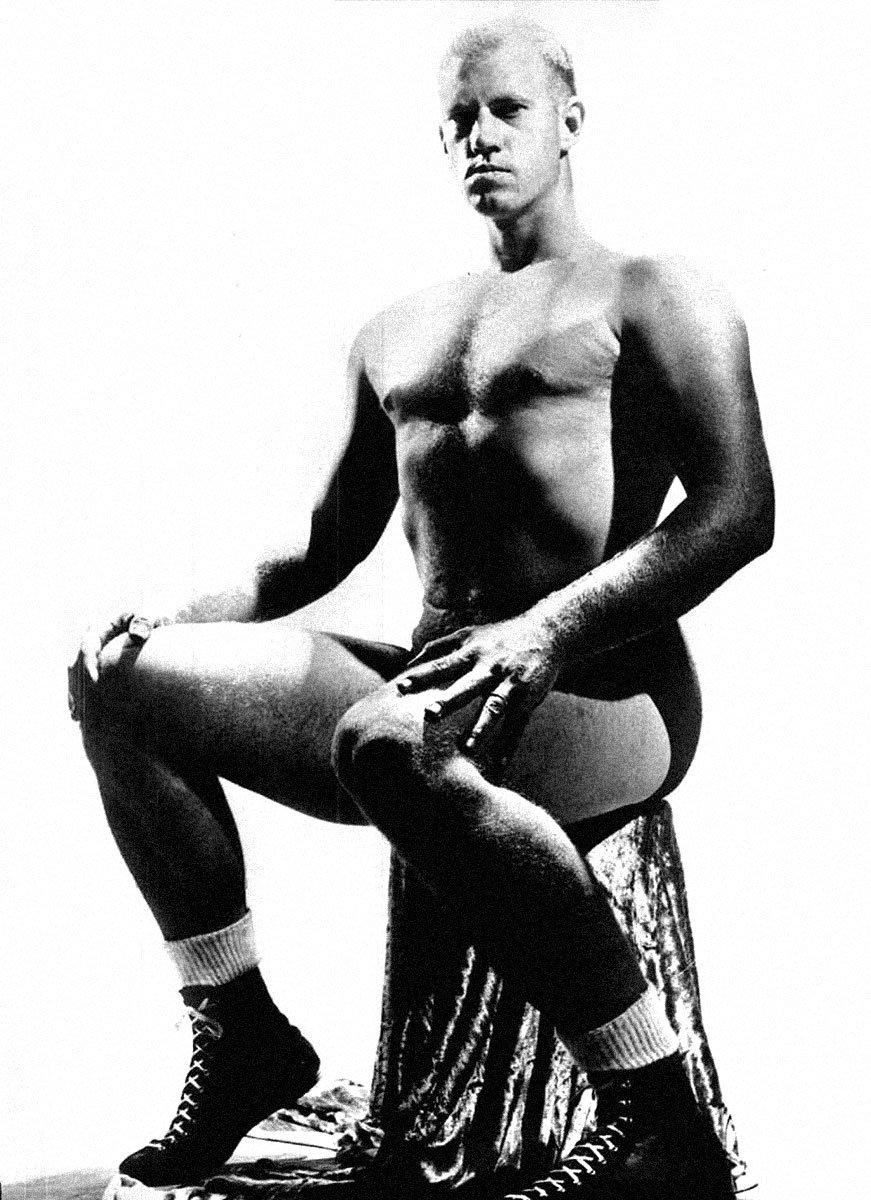

Time has dealt malevolently with the old wrestler. Fritz, 58, limps from a long-ago injury. His face looks like a jutting cliff of granite, each muscle and vein stabbing from his skin. His head is as large as a bowling ball, his arms the size of hams. He nearly crushed my hand when he shook it; his own hands looked as if they had been broken in a fight and had not entirely healed.

Slowly, Fritz lowered his massive body into a seat at the kitchen table. Doris watched the swaying of her husband’s figure and gave a thin, pleased smile. She had been softly encouraging Fritz to spend more time at home. She would send him off on errands or have friends meet them for lunch in the nearby town of Edom. She would ask him why he wasn’t spending more time on his bulldozer, driving around the property, clearing land.

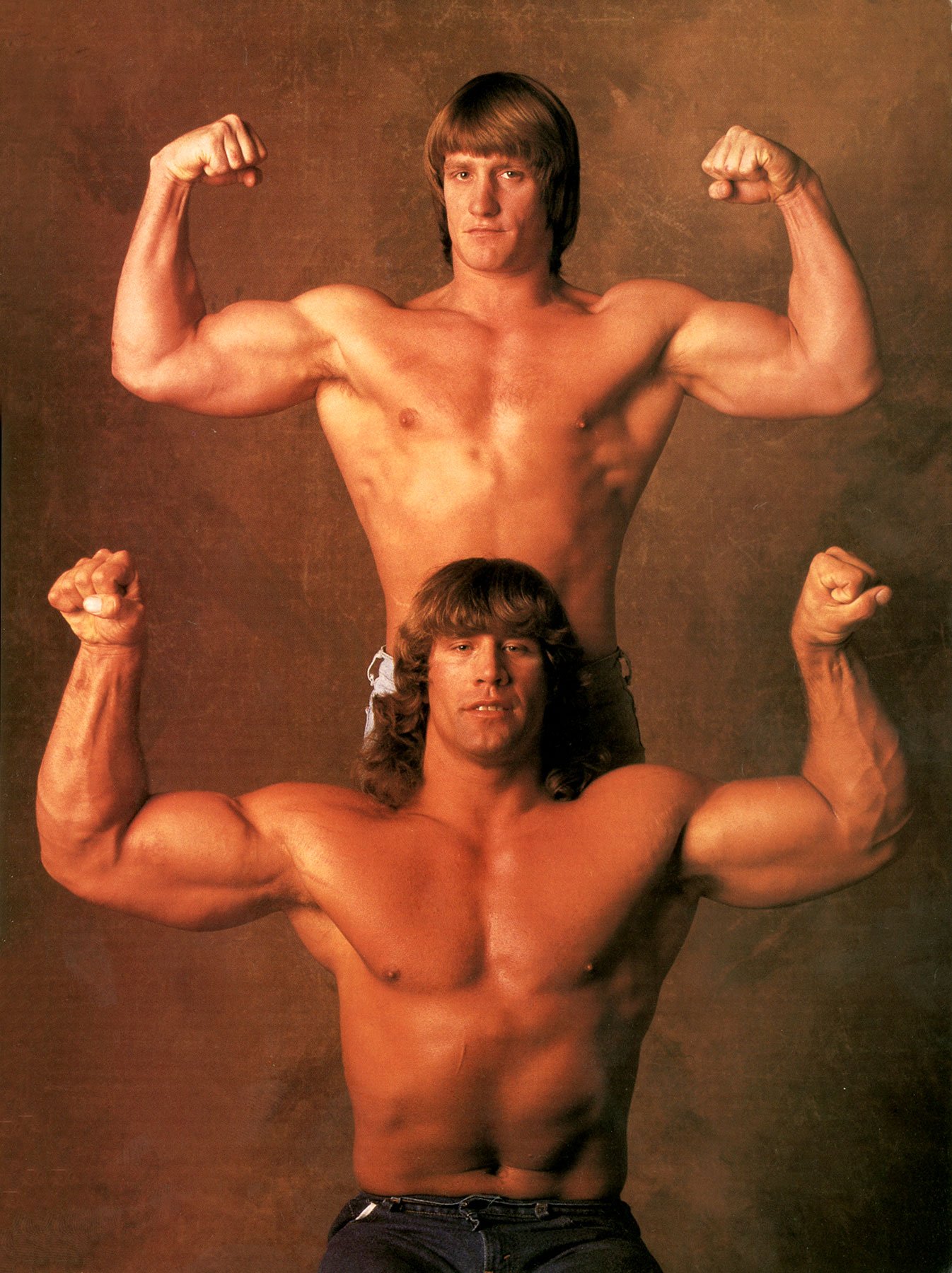

But though Fritz had been trying to ease away from the family wrestling business, events kept bringing him back. On this day, his nerves were as tight as a wound-up fiddle string. Not only was there the matter of the Penthouse reporter, but Fritz was worried about the upcoming Thanksgiving night show, where Reunion Arena had been booked for what had been billed as Kerry Von Erich’s “triumphant return to the ring.” A few years ago, this would have been an easy sell-out house. In 1984, the Von Erichs drew 41,000 to Texas Stadium for what was then the largest audience ever to see a wrestling match in North America. At the time, Kerry had been named the most popular wrestler in the country by national wrestling magazines, more popular even than Hulk Hogan. He looked like Samson, with his long curly hair and magnificent body. He was followed by thousands of teenage girls, the first true pinup star in wrestling. A national tour was planned. The Von Erichs were poised to become the first family of American wrestling. But then came the deaths of David and Mike, and the motorcycle wreck that knocked Kerry out of the ring for 16 months. As hard as he tried, Kevin, the quiet, oldest son and the one most fiercely loyal to the family name, couldn’t sustain the Von Erich image by himself. (Chris, the youngest son, suffers from severe asthma and has not yet entered the ring.) Attendance began plummeting at the weekly matches in the Sportatorium, from 2,000 in the Von Erichs’ heyday in the early ’80s to sparse crowds of 300. Wrestling fans had other shows to pick from now. Old Fritz knew that if Kerry’s comeback at Reunion Arena wasn’t successful, the Von Erichs might be finished.

To understand how the Von Erichs could hold such unyielding devotion to a business that has turned their lives upside down, that has brought them demons along with applause, that has killed off their sons, it is important to understand Fritz himself and how his life has been hammered into the lives of his sons. “It sounds so odd to other people,” said Doris, “but the boys never felt they had to be different than their dad. They even encouraged each other to be like their father. I kept trying to tell them they could be any way they wanted. They could always be an Adkisson. They could go into art or music if they wanted. But finally, I had to admit that only one thing was important for them: to take on the Von Erich name.”

When Fritz Von Erich decided to go into wrestling in the early ’50s, the business had little of the glamour or rewards that it has today. Wrestlers spent long hours driving from one dank auditorium to another; Fritz would often wrestle for all of $5 a night. One time, after a match, a fan was so angered at Fritz’s antics in the ring that she stabbed him in the buttocks with a six-inch hatpin.

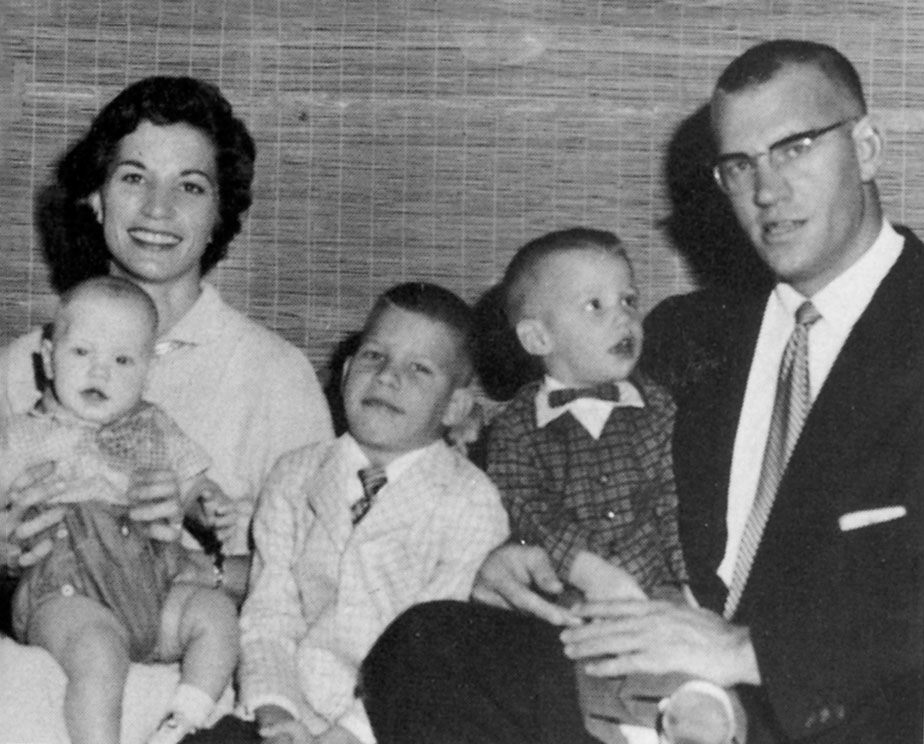

Even in the late ’50s, when Fritz had come up with the infamous “Iron Claw” (spreading his huge hand over an opponent’s face, then squeezing) and promoters from all over the country and Canada were calling for him, he was not getting rich. He and Doris lived in a trailer park in Niagara Falls, New York. She had given birth to their first son, Jackie, in 1952, followed by Kevin in 1957 and David a year later. Then, in 1959, while Fritz was out of town on a wrestling trip, Jackie, then 7, touched a live wire while he was playing in the trailer park. Electrocuted, he fell down face first in a puddle of melting snow and drowned. It was a nightmare for Fritz and his wife. Doris felt herself going weak; she told her husband she wanted to die too. Years later, she would still judge time by recalling her first son’s death (“It happened nearly 12 years after Jackie died,” she will say about some family event). The death of Jackie put the Von Erichs through the same kind of emotional ordeal that draws many to watch professional wrestling: they often felt like helpless spectators of their own lives who would wait through each day to see what new misfortune the world had in store. But after the loss of his son, Fritz returned to the ring with a vengeance. At least here, Fritz found a way to force his will on at least one corner of life.

Even those who cared nothing about wrestling were fascinated by the Von Erichs.

A month after Jackie’s death, Doris was pregnant again, this time with Kerry. Fritz had decided to move back to Dallas and raise his remaining sons out in the country, where he would always be close to them. He bought a 115-acre spread near Lake Dallas, far from the encroachment of civilization. “We grew up alone,” said Kevin, “just ourselves. I guess one of the first lessons we learned was that the only people you had to count on was your family. The lesson stuck: a couple of years ago, when Kevin, who’s 30, bought a house near Roanoke, northwest of Dallas, Kerry, 27, promptly went out and bought a home two doors away.

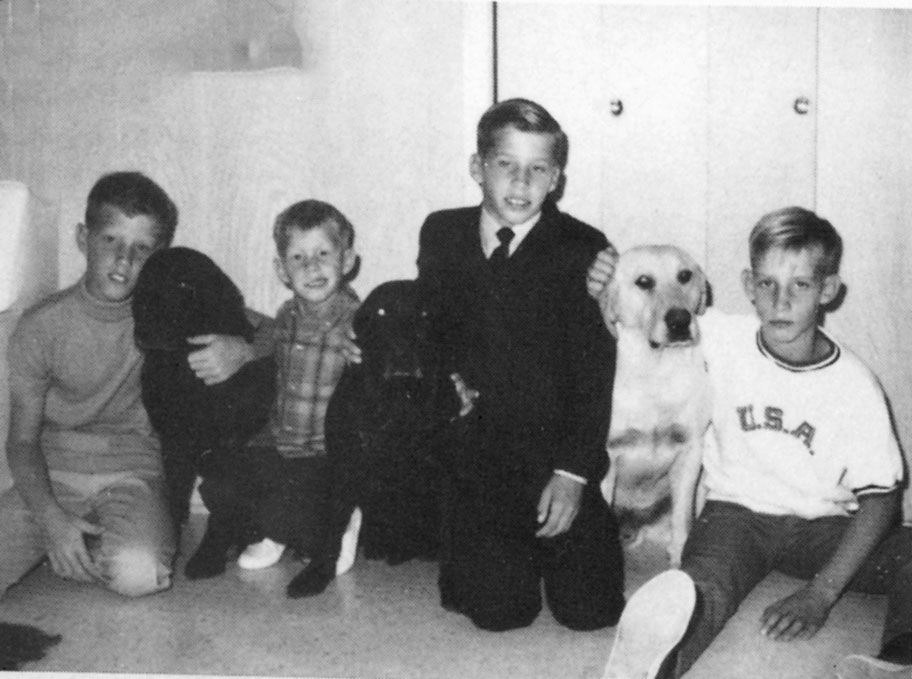

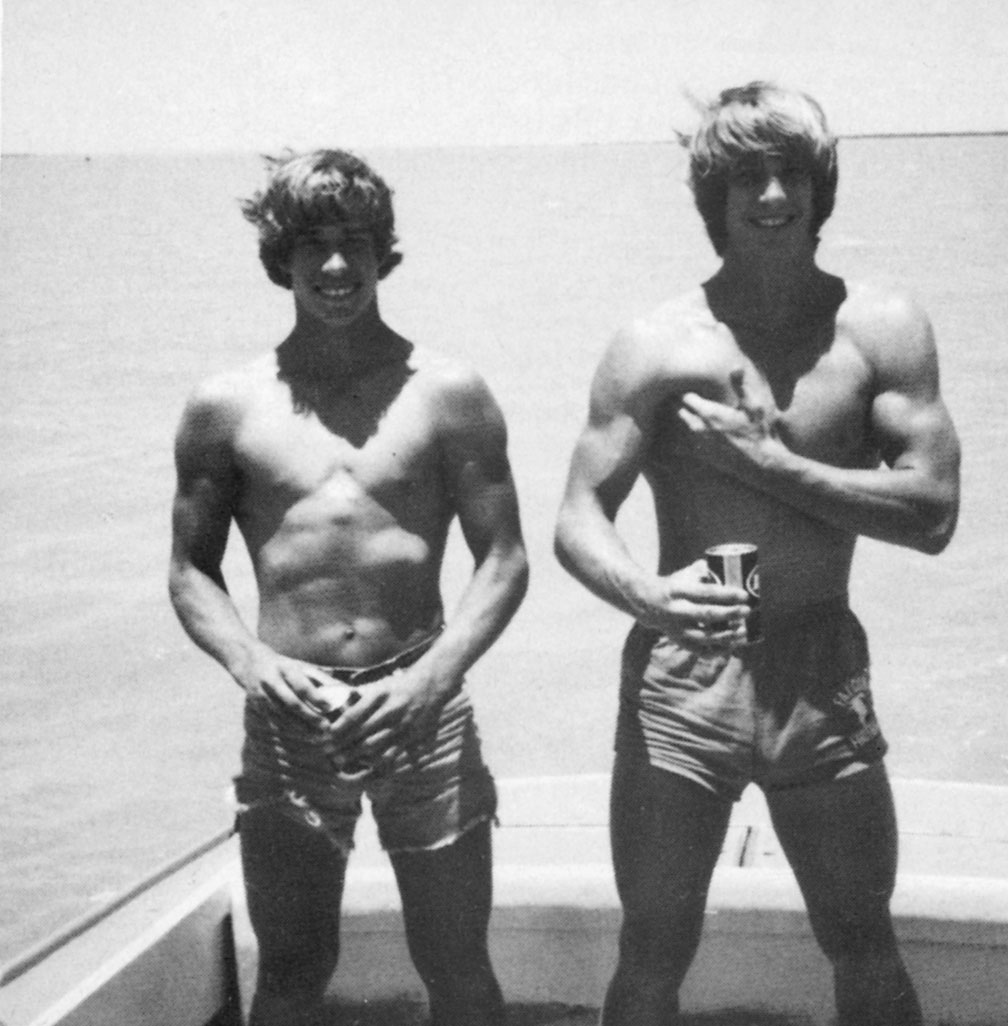

Growing up, the Von Erich boys had the kind of charmed country existence that people have in mind when they talk about “the way life used to be.” The kids romped through the woods. They had eight Labrador retrievers. They drank 32 gallons of milk a week. They once set fire to a field trying to kill one mouse and covered speed limit signs on the farm-to-market highways with mud. Whenever the boys got out of hand, Fritz dealt out quick, painful justice with one of the leather straps hanging in his closet.

“Did you ever think you were too hard on your kids?” I asked Fritz.

“Absolutely hell no,” he said. “One time Kerry yelled at me that he shouldn’t get a beating, so I tore his butt off even harder.”

But Fritz loved his sons as intensely as he dominated them: he taught them to hunt and how to ride motorcycles, and, of course, how to wrestle. By the time Kevin was 6, there was a wrestling ring set up in the back of the house. Fritz also told his sons to fight back if a bully was picking on them. “It’ll hurt if you get your nose bloodied,” he’d tell them, “but your self-respect will never go away.” Kevin said the brothers would go up to other boys their age and politely ask if they wanted to fight — “not because we were picking on them, but because we thought it was the natural thing to do.” The Von Erich boys would take turns walking around the house in their dad’s huge, size 14 wrestling shoes. They would go with him to the Sportatorium to watch him in the ring, and he would go to all their Pee Wee football games. At home, he’d make the kids work out, lifting weights in the gym he set up. He told them they should be in sports, because sports is a test for life. When Kerry became interested in the discus, Fritz, a former discus star himself, built a ring in a pasture behind the house. He collected films of famous discus throwers and coached Kerry two hours a day.

After successful high school football, basketball, and track and field careers—Kevin, David, and Kerry became the first three All-State athletes from Lake Dallas High School, and Kerry set a junior world discus record — the three brothers went on to college. But they all quit to become professional wrestlers. The wrestling ring, for reasons even the Von Erichs may not understand, represents a center of gravity to this family. The sons assumed the best way to test their own character, to discover who they really were, was to wrestle. “Dad never, ever said we had to wrestle, or that we even ought to,” said Kevin, the contemplative, soft-spoken son who outside the ring seems so far removed from wrestling’s exaggerations. “To be honest, we didn’t even know if we’d like wrestling that much. I mean, wrestling was filled with these old, out-of-shape men, going from one small town to another, looking miserable.”

Kevin paused. “But we all knew what was going to happen in the end. It was inevitable. We were going to go into wrestling because we wanted to be just like our dad.”

Whenever I was around the entire Von Erich family, it would occur to me that families don’t grow up like this anymore. The Von Erichs were, in a way, representative of a time that has vanished. I felt an eerie sense of camaraderie among them. With instinctive gestures of kindness, they would touch one another on the arm, look deeply into one another’s eyes, and say things that sounded as if they had come from an old Father Knows Best dialogue.

Fritz (talking one afternoon about a future project): “Now, Kerry, son, what do you think about this?”

Kerry: “Well, gosh, Dad, you know how I love you. But are you sure that’s right?”

Fritz: “It’s right, Kerry, I’m pretty dadburn sure it is.”

Kerry: “I’m with you, Dad. Yes, sir, I am. You know how I trust your opinion on that.”

I asked Kerry if he ever wanted to rebel at anything, to strike out on his own. Did he ever think about doing something other than becoming a Von Erich?

“Well,” he said, “when I started setting the discus records, I wanted to be known as Kerry Adkisson, not just Fritz Von Erich’s son. But then I felt sort of bad about that, so I let people call me Kerry Von Erich.”

The fifth son, Mike, who was born in 1964, and the youngest son, Chris, born in 1969, grew up in the shadow of Kevin, David, and Kerry. Mike, too, showed promising athletic skills in high school, “but I think he always felt a lot more pressure on him,” said Kerry, “being in a family of overachievers. Here he was, with three older brothers who were never happy unless they did their best. Mike was thrown into that life in an awful hurry.”

And so, for better or worse, by the late ’70s the Adkisson boys were ready to assume their new roles as folk heroes. The champions of goodness, they would bring down the wrestlers of darkness, and all would be well until the next week’s match.

• • •

To understand how the Von Erichs became powerful, one must never forget the domineering force of Fritz himself. When Fritz returned to Dallas in the early ’60s, he became a partner in the local wrestling promotion company that was staging matches at the Sportatorium. Back then, Dallas wrestling was nearly nonexistent — “the wrestlers were a bunch of old fools,” said Fritz — and it didn’t make much financial sense for Fritz, who was more famous in other parts of the country than in his own hometown, to wrestle here.

But this was his chance to establish his own kingdom. In those days the country was divided into regions. Among the major wrestling promoters, it was a little like the Mafia: each promoter had his own territory, and there was a gentlemen’s agreement that another outside promoter wouldn’t invade it.

Moreover, each territory had its own champion, who held what was called the American belt. All the promoters would also recognize one world champion, who in turn would travel around the country fighting the different American belt holders. The system worked well because each promoter not only could develop his own stars, but expect a huge audience whenever the world champion came to town. Though some cynics claimed that the promoters would regularly get together and decide who would become the next world champion, the promoters vehemently argued that the championship was always decided in the ring.

Texas quickly became known as Fritz Von Erich territory, and nationally known wrestlers began to come here. They had heard of Fritz’s reputation as a master of marketing. Channel 11 televised his weekly matches in Fort Worth, and Channel 39 showed the matches from Dallas. They became the highest-rated shows for each station: the bad guys always seemed to win in Fort Worth, but the good guys would come back to win in Dallas. And always in the middle was Fritz, then the great villain. On the television shows, he’d grab the microphone from the announcer, turn to the camera, and begin threatening his opponents so venomously that it was almost hypnotic to watch. For those who loved wrestling, the bombastic Fritz became the focus of a tribal glee, for here was a man taking things into his own hands.

But as his sons prepared to enter the ring, Fritz very carefully changed his image. He knew what he was doing — the Von Erichs were about to become the symbol of the rugged, tough but clean-living family. They would always fight fair, and their dad would always be right there supporting them.

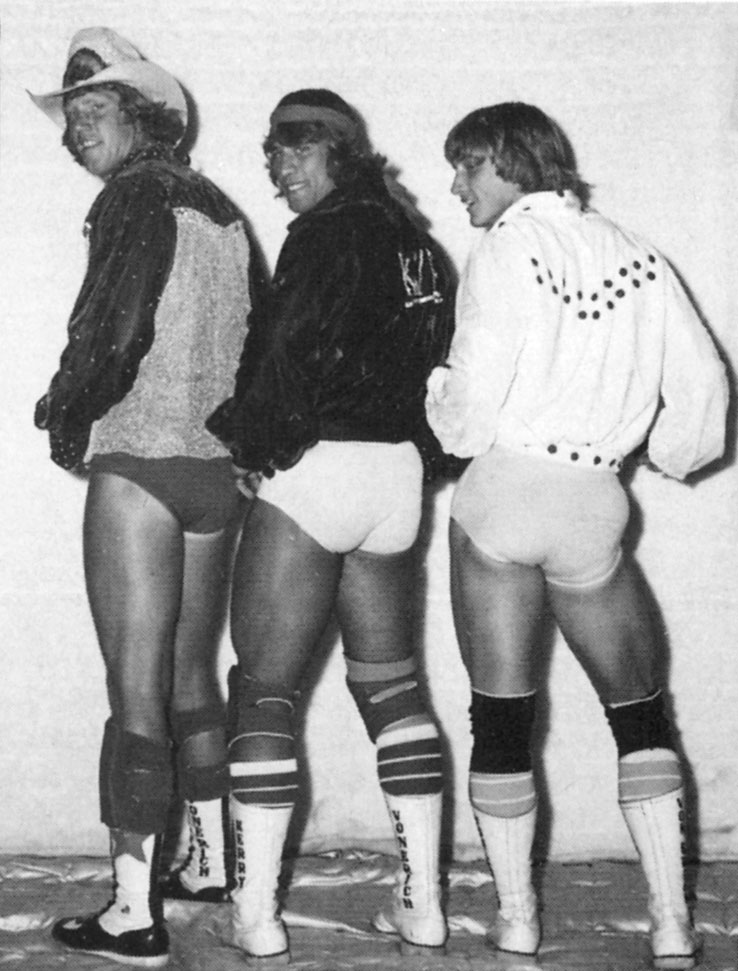

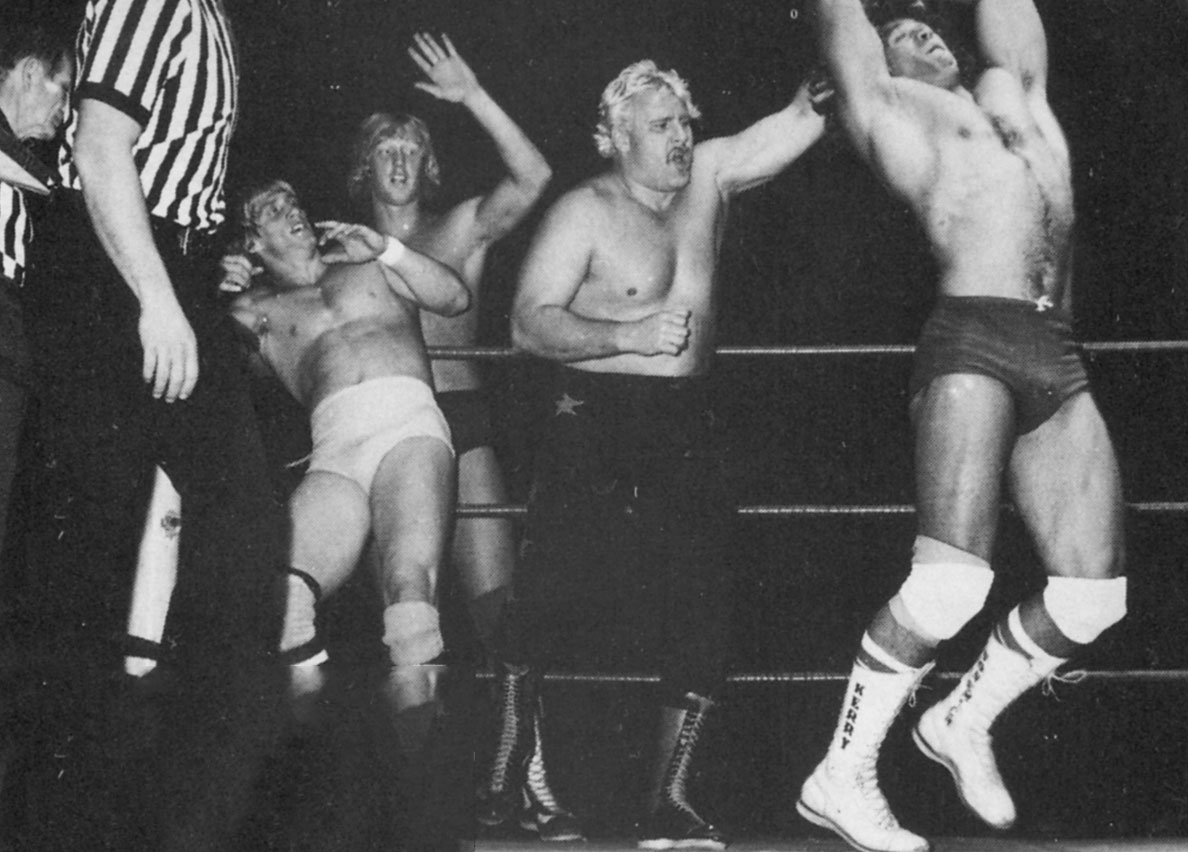

No one really had any idea how popular the new personas would become. In 1982, three wild, bad-assed Southern wrestlers called the Freebirds were brought in to wrestle Kerry, David, and Kevin. The Von Erich boys needed rivals, and the Freebirds were perfect. They were cast as cheating, beer-drinking outlaws, and they would get on television and rant about the Von Erichs’ squeaky clean appearance. They’d call them “daddy’s boys” — and wrestling fans everywhere loved it.

“There had never been a rivalry like that before in professional wrestling,” said Dave Meltzer, who publishes the Wrestling Observer, a newsletter for the wrestling industry. “It was beautifully set up, and it made the Von Erichs national celebrities long before other wrestlers, like Hulk Hogan, became celebrities.”

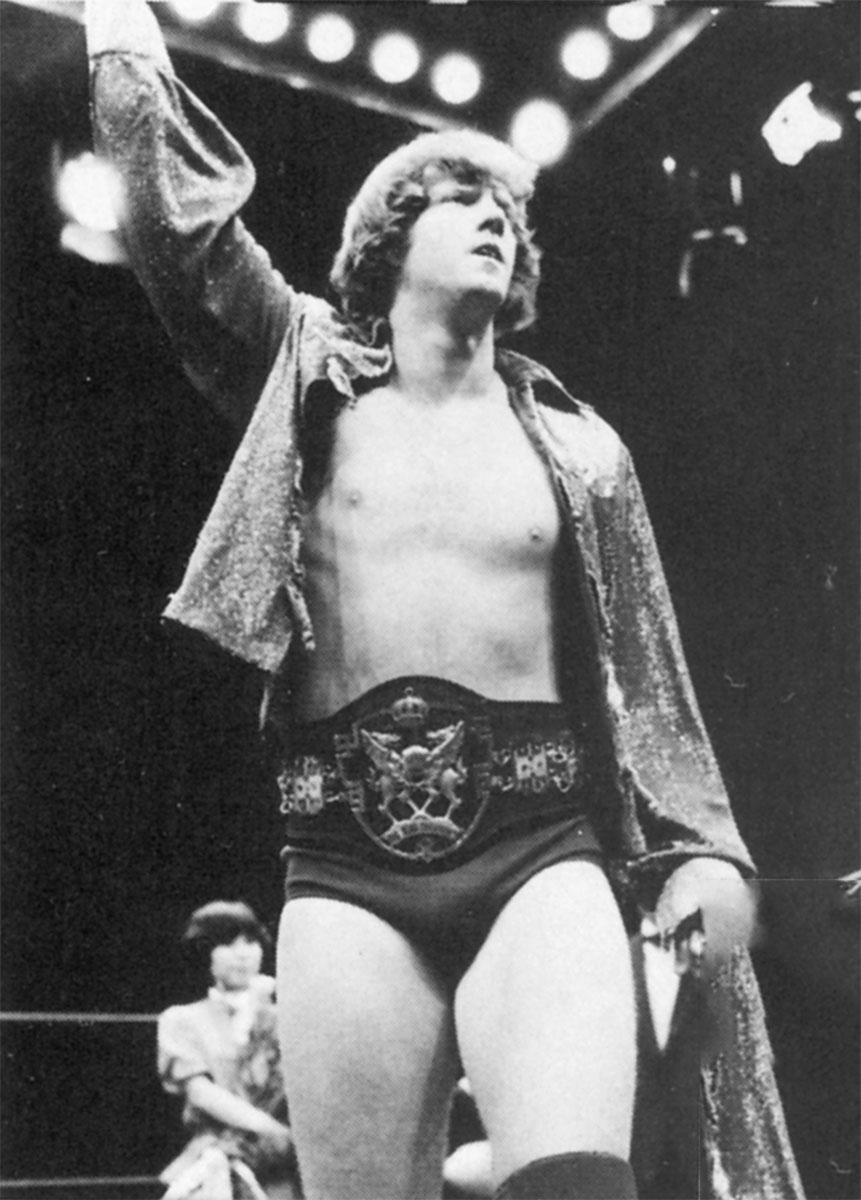

It was mind-boggling that wrestling, the theater of the absurd, could produce such superstars. But even those who considered wrestling a staged series of antics found themselves more than a little entertained by the Von Erichs’ colossal battles. The sons began to capture a certain part of many people’s imaginations, and the action was too enthralling to interrupt with serious questions. Nearly 15,000 people came out in 1984 to see the sons make a token appearance at Town East Mall in Mesquite. The first time Kerry wrestled in Chicago, 37,000 people filled Comiskey Park, chanting his name even before the matches began. At least 200,000 households in Dallas-Fort Worth were watching the Von Erichs’ weekly show in 1984; but the program also went to 60 markets in the U.S. and into Japan and the Middle East, and black market copies of the show were being shown in such far-off countries as Nigeria. There was even the Von Erich Fan Club of Israel — members would make visits to the Wailing Wall in the Old City of Jerusalem to pray for the family.

In 1984, Mike, still raw and inexperienced at age 20, was voted rookie of the year by one national wrestling magazine. Another wrestling magazine voted Kevin man of the year and named Kerry the most popular. The sons suddenly found themselves in the harsh glare of the public spotlight. Though all four of them had married at early ages, they always pretended to be single so they wouldn’t lose the adoration of their thousands of teenage girl fans. Their father demanded that they not drink in public. They did not turn away an autograph seeker. All of them became born-again Christians, and they would deliver their testimonies with such mesmerizing conviction that hundreds would answer the altar call at the end of the service. “At first,” said Kevin in an unguarded moment, “we went into wrestling because it was fun. But when all the attention hit, we realized just how important this could be, not just for our family, but for other people. I’ll tell you something” — and there was a kind of steely glint in his eyes as he spoke. “It didn’t become a performance anymore. It wasn’t an act. We became the Von Erichs, we began to think we were everything they represented, and that is what we are now.”

When one watches a good professional wrestling match, it is hard to know what is real and what is pure showmanship. But there was nothing like the shadow world of the Von Erichs. People would peer at their television sets, watching the sons shout at the villain of the week — whether it would be Michael Hayes or the Dingo Warrior or Bruiser Brody — and they would think, “Surely, they can’t care that much.”

“Bullshit,” said Kerry, showing a rare flash of his fiery temper. “It was all we cared about.”

Indeed, the Adkisson boys had disappeared into their roles. In the ring, the sons seemed so much more alive and vigorous than ordinary people — but that is exactly where reality caught up with them. In February 1984, David, at age 25, died while on a wrestling tour in Japan.

• • •

David Von Erich was the biggest and the most temperamental of the Von Erich sons, as domineering in the ring as his father had been, and almost impervious to injuries. But in late 1983, a few months before a big trip to Japan, where the Von Erichs were revered as much as they were in the U.S., he began to throw up. He had some kind of stomach sickness, he told his family, but he said it would go away. Then, in his Tokyo hotel room, he fell down dead. There were a lot of rumors, as there always are about famous people who die suddenly. The Penthouse reporter had asked a Von Erich business associate if drugs had killed David. Furious, Fritz showed me a copy of the death report from the U.S. Embassy in Japan, which clearly said David died from “acute enteritis,” a severe intestinal infection.

As his sons prepared to enter the ring, Fritz changed his image.

David’s funeral was simply astonishing. Anyone who still doubted the impact of the Von Erichs could no longer deny it then. More than 1,000 people packed First Baptist Church in Denton, and 2,000 more gathered outside. The balcony was like something out of a Beatles concert — teenage girls sobbing and hysterical. On each side of the closed casket were portraits of David. One minister’s eulogy described how David was in the end victorious because he won his “match with the Devil.” Channel 39 later ran an hour-long television special on David’s life, showing the large, happy-faced kid copying his father’s great hold, the Iron Claw, for the first time: David’s eyes grew wide as blood seeped out of the head of his opponent.

When I asked Fritz and Doris about David’s death, Doris gazed about the kitchen, as if she didn’t know where she was. “Well,” she said, “he told me he was feeling better, and I believed him.”

Fritz (to Doris, after a lengthy pause): “Mother, I don’t know if I ever told you this. Did you know David called me the day he left for Japan?”

Doris (putting her hand to her mouth): “David?”

Fritz (sighing): “Mother, he told me he didn’t feel like going. But he said, ’Dad, when I get there. I’ll be okay.’ I said, ’David, that’s the way it is, son. You’ve got a contract. Those people over there have sold out a building to see a Von Erich.’ And he said, ’Dad, I’m going.’”

Doris, by her coffee pot, began crying softly. There was a kind of power about her face — a handsomeness that had been coarsened by years of grief and disappointment. She once told me that during all the times she has felt life receding from her, like the sea being pulled away by the tide, she has never complained.

Fritz: “My God, how were we to know what he was feeling?”

Doris: “Oh, Fritz, you can’t know everything. You just can’t. The older you get, the less you know.”

Fritz (rubbing his massive hands together): “Mother, I wish I knew what to say. What can you do about the things life deals you, except hang on?”

The family’s inherent sense of drama led them to create, a few months after David’s death, a memorial match at Texas Stadium in David’s honor. In front of 41,000. Fritz came out of retirement to help Kevin and Mike beat the Freebirds. And Kerry defeated the reigning world champion, Rick Flair, to gain the world championship belt for the first time. “David was right there next to me,” Kerry told reporters, and it truly did seem for a while that David’s death would only add to the Von Erich mystique.

But a year later, Mike was suddenly rushed to the hospital with toxic shock syndrome; a rare bacteria apparently entered his body when he was undergoing surgery on a shoulder that he hurt while wrestling. His temperature soared to 107 degrees, his weight dropped 50 pounds, and most of his organs suffered significant damage. For days, he could only respond to questions by blinking his eyes. At one point Baylor Hospital was receiving 400 calls an hour from well-wishers, but the doctors gave Mike little chance of living. “He will live!” Fritz boomed at the doctors down the hallway, and he led his family into a room to pray. Miraculously, Mike did survive. In their testimonies to the churches, Fritz and his sons said that God had given them a miracle. Still, those who knew Mike well knew he would never be the same again.

And then, a year later, in June 1986, Kerry slammed into a police car with his motorcycle and required 15 hours of surgery on his foot. Doctors had trouble restoring blood flow through the leg; they inserted pins and needles into the foot and had to fuse part of the bone. There was a chance, doctors said, that Kerry could return to the ring, but he, too, might never be the same.

It was a freakish turn of events, this fall of the house of Von Erich. The legend was no longer some Homeric epic of young heroes fighting alongside their daddy. It had become a soap opera. Everyone wanted to know what disaster would happen next. Fritz was reeling. To bolster the family image — and because he was running out of sons who could wrestle — he made a desperate move, bringing in a handsome young wrestler from Oregon named Kevin Vaughn. Fritz renamed him Lance Von Erich and told the wrestling audience that he was a distant cousin. In retrospect, of course, it was a mistake, one that did nothing but knock a hole in the integrity of the Von Erich family. Many loyal Von Erich believers doubted the story from the start, even when the sons would talk about how they grew up playing with cousin Lance. The new Von Erich didn’t even wrestle that well. But he did go to Fritz demanding a lot more money. Fritz, outraged, said no, and Lance left to join a rival promoter — leaving the Von Erich family back where they started, and even more humiliated.

Amazingly, Mike Von Erich tried to return to wrestling — but the toxic shock had done its damage. His coordination was off; in one match he tried to execute a dropkick and landed right on his face. Sadly, the high fever he suffered had done something to his memory as well. Mike would begin a wrestling move, and then just stop, as if he had forgotten exactly what he was trying to do. At a match in Austin, he grabbed the microphone to take up for his brothers and yell, in the great Von Erich tradition, at the evil enemy — but suddenly he forgot what he was supposed to say, and he just stood there open-mouthed.

Kerry also tried to come back. He went into the ring for what was called a “workout match,” and he injured his foot even more. “It was just a nightmare,” said Kevin, the only Von Erich who still seemed fit to wrestle. “A damned nightmare. I thought, ’It’s all going. We’re all finished.’ I’d look out and watch Mike trying to wrestle, knowing how badly he felt, and I knew how much he wanted to keep up the family name, and I just couldn’t believe how sad it all was.”

Fritz’s sons were going down, and the business was changing around him. Due to a stream of glowing publicity from the mainstream press (Sports Illustrated even ran a cover story on “Wrestlemania”), professional wrestling competition nationwide went through a major upheaval in the mid-’80s. Television networks and syndicates clamored for wrestling shows. In 1986, a Dallas viewer could see 44 hours of televised wrestling a week; two years before that, he only got the shows starring the Von Erichs. Wrestlers’ salaries began to go through the roof: top-level wrestlers who were making $200,000 in the late ’70s were now fetching $2 million a year.

Moreover, the new breed of wrestling promoters that had emerged cared nothing for the old rules. Several organizations came into Dallas to run shows, including promoters from other territories. Fritz thought the newcomers would adhere to the way things used to be. but he was wrong. The World Wrestling Federation, which had such stars as Hulk Hogan and Roddy Piper, created a nationwide wrestling circuit. Fritz even found his top talent being lured away, including the infamous Freebirds and popular tag teams like the Fantastiks. One of the best wrestlers who stayed with the Von Erich camp, Gino Hernandez, died of a cocaine overdose. To add further insult, some of Fritz’s business associates had gone off to start their own competing promotions: one of Fritz’s closest allies, Ken Mantell, began the Wild West Wrestling organization in Fort Worth. Fritz admitted that he was “getting left in the dust.”

In a final move of retaliation, Fritz’s organization, which still ran professional wrestling in Dallas/Fort Worth, decided to break away from all other wrestling organizations, form its own federation, and declare a separate world champion. Fritz bitterly claimed that the National Wrestling Association, the organization that supervised most of the country’s major wrestling territories, had not been giving his sons enough chances to win the world title. Under the new federation, to no one’s surprise, Kevin soon became the world champion, and in late 1986, plans were announced to start a major Von Erich Over America tour. The sons would hit every major city in the country.

But even that failed to attract much attention. What did get the Von Erichs back in the headlines, incredibly, was another tragedy.

Mike Von Erich, 23 years old, committed suicide.

• • •

Last April 16, police found a body curled up in an old sleeping bag in a dense grove of woods a few hundred yards away from the Von Erich boyhood home. After being arrested for DWI, Mike had driven out to the old stomping grounds and taken a lethal overdose of tranquilizers. Police found his wrestling boots in the back seat of his car, along with a note addressed to his mother. “Mom,” it began, “you have always been wonderful. I am in a better place.”

Mike was the son who had always quietly gone to visit handicapped kids; the son who, without telling anyone, had been giving money to a poor older lady who lived near him. But, for him, that wasn’t enough. “I don’t think Mike was ever really sure he felt good enough to take on the Von Erich role,” said Kerry. “I mean, it churned him up inside that he wasn’t as quick or as strong as the rest of us. And after the toxic shock, when he started losing his balance on the top ropes, or missing a hold or something, he thought he had lost part of himself, you know what I mean?”

“He was so private,” said Kevin, “that he would not tell people the pressure he felt to keep up. We’d say, ’Mike, if you don’t want to do it anymore, quit!’ And he would just look at us. I don’t think he wanted to disappoint anyone. I know he didn’t want to disappoint Dad.”

A few days before his death, Mike had come to his mother and told her he was scared. He was afraid that in a year or two, something in his body was going to stop working. What would he do if something went wrong and he couldn’t make a living? Doris tried to comfort him: “Mike, don’t worry about it. This family will always be with you.”

But, perhaps for the first time, the family was staggered with the realization that the Von Erich name could be too big a mantle for some of them to bear. It certainly had become too big for their sensitive young son. This time, there was no great public declaration of grief. There was no memorial match: only the arena bell ringing 10 times in tribute while the crowd stood silently. The Von Erichs’ life was turning into a state of siege; they were always losing just what they wanted to keep.

“You have to go where you destiny leads you. And for us, this is it.”

Why, I asked Fritz and Doris, did Mike, obviously in poor condition after the toxic shock, feel a need to wrestle again? And why did they let him?

“He wanted to more than anything,” Doris said. “That’s all he would tell us he wanted.”

Fritz cut in, “Good Lord, how could I ever tell him that he couldn’t go back in the ring, that his body wasn’t right? How could I?”

“How do you tell someone that his passion is over?” Doris asked, her voice quavering. “How can I tell my youngest. Chris, that his asthma might keep him out of wrestling? Every day, he lifts weights. He dreams about being like his brothers. Do I dare go out there and break his heart?”

For the Von Erichs, it seems, wrestling is much more than a vocation. It is a calling, and they have used it to speak to so many people, to tell stories about courage and endurance. Before I left their home one afternoon, Fritz leaned his massive body toward me and said, “I spent a lifetime building this, and we can’t stop believing in it. No one is going to take it away from us. Kerry is going to come back. Kevin will always be there. We will never throw in the towel.”

Outside, we all looked up in the sky. The wind had died, and the air was clear. The Canadian geese had not returned.

• • •

On Thanksgiving night I went to Reunion Arena to watch the “triumphant return of Kerry.” Of the some 2,000 who had also come, I saw more adults than I had expected, people from the working class whose faces seemed to know all about struggle. They, too, needed someone big and strong to believe in. Into the ring came one set of wrestlers after another, their styled belligerence not so much beautiful to these fans as it was something far more intriguing — primitive and alive.

Backstage, Fritz was leaning against a wall. He looked tired, his arms held loosely down at his sides, his hair growing transparent at the back of his head, his eyes glazed with stoic chagrin. Doris was nearby, sitting properly in a chair. Down the hall was Kerry, stretching. Because of the injury, he didn’t seem to have the mobility to make those famous soaring dropkicks, and he had lost some of his speed, but he had spent much of his 16-month convalescence in the weight room. Amazingly, there were even more muscles packed into his bulky frame. The last time I had seen him, he was sitting happily in a chair at his pretty Victorian house, while his two little girls climbed all over him and pulled at his ears. Now, wearing an Elvis-style sequined white robe with “Kerry” on the back, the star wrestler had a look on his face that I could only describe as murderous. “I am ready,” he said.

Fritz came up and motioned to me. “I have something to tell you,” he said, then stopped.

I waited. In the distance the crowd roared, then stopped, then roared again.

“I’ve decided to retire and get out,” he said. His voice was so low it sounded as if it needed oiling.

He said, “Kevin and Kerry will still keep wrestling. But someone else is going to take over. I’m just tired. I’ve got to get out of the business.”

Then, Kevin came up and said, “Dad, we’re on.” And the two of them headed through the doors toward the ring.

Fritz was selling out his financial interest in the company that promoted his and his son’s careers, He had decided to make only rare public appearances. There had been reports that poor ticket sales for matches over the last couple of years had financially hurt Fritz; he had spent a lot of money trying to uphold the family image. Ken Mantell, his old business partner who had once left him in an angry split, was returning to run the wrestling promotion. “Fritz is an old warrior,” Doris said. “He’d like to build the business back up himself and make his sons the most famous wrestlers in the country. But you can’t have lost as much as he has without it doing something to you. He talks about never giving up, but you know, he’s worked for so long. I think he’s ready to sit out on the porch and watch the sun set.”

It seemed to be one more signal that the Von Erich dynasty was coming to an end. Nevertheless, out by the ring, Fritz, acting as Kevin’s manager, was entertaining the crowd in the way that only he could. The ring announcer, referring to some vague rule, said that Fritz had to be locked in a cage while Kevin wrestled. The bald-headed Gary Hart, Fritz’s arch-nemesis and the manager for another wrestler, began taunting Fritz, throwing him monkey food, calling him names. Inside the ring, the barefoot Kevin slammed against the ropes and fired himself across the mat like a stone from a catapult. He climbed on top of a turnbuckle and swan-dived onto his opponent. Meanwhile, Fritz beckoned Hart to come close. The crowd was in an uproar. Suddenly, as Kevin pinned his opponent to the mat, Fritz reached out, grabbed Hart, and began banging his head into the bars of the cage.

Then, when Kerry came out for his 20 minutes of routine fury, the arena nearly exploded. For these fans, the hero had returned. He took on his rival, Brian Adias, used the Iron Claw, choked him around the neck, spun him around, and swung him off his feet. He then lifted Adias over his head and slammed him into the mat. Adias, helpless, seemed lost, his mouth half open in agony. When some of Adias’ villainous comrades sneaked into the ring to try to gang up on Kerry, out came Kevin, the loyal brother, to help save another Von Erich victory. The crowd had seen it all a hundred times before, this ritual of betrayal and triumph, and still they cheered so passionately it was as if they had just found the missing element to the drama of their lives.

When the two brothers stood in the middle of the ring, their hands held high, I noticed that Fritz was in the tunnel near the dressing room door, half-hidden in shadow, staring at his sons. Doris was not far away, her eyes gleaming. There was still something magnificent about them, something that suggested the character of a bygone era. “I’ll miss it,” said Fritz, “but my God, I’m tired.”

“I guess this is our destiny,” Kevin told me once, “and there’s nothing more to be said about it. You have to go where your destiny leads you, no matter where that road might be. And for us, this is it.”

40Gr8

Author