On its fiftieth anniversary in 1966, Southern Methodist University, under the leadership of Emmie Baine, its dean of women, awakened a sleeping giant in Dallas.

The name and character of the event were in-nocuous enough. Called a Symposium on the Education of Women for Social and Political Leadership, the meeting presented a series of speakers with impeccable credentials, among them Mary Bunting, president of Radcliffe College; Carl Degler of Vassar; Marietta Tree, the first woman ambassador to the United Nations; and Aileen Hernandez from the Office of Economic Opportunity, Washington, D.C.

At any other time or in any other place this program might have been just another intellectual exercise presented to a polite group of selected women. But in the Dallas of 1966, it fanned the embers of the smoldering women’s movement and ignited a flame that has burned slowly-sometimes almost going out-but flickered again and again to this day.

It has changed the way Dallas looks and functions, altered the personal lives of countless individuals, and created a climate for possible future gender equality. It has done all this without violent confrontation and without general public knowledge, awareness, or approval. It has been, largely, a silent revolution with each person cognizant only of the issues that have touched his or her life personally and with most newcomers and most people under thirty-five convinced that nothing of any major significance relating to the women’s movement ever happened in Dallas.

They are wrong, of course, To understand what did happen, you have to move back in time-back to the days when to be born female in Texas was to be legally and socially bound, first to your father and then to your husband. By law, three classes of people were incompetent to give legal consent in those days-idiots, imbeciles, and women. The only way a woman could manage her own affairs, including property she inherited, was to have her incompetent status removed by law, to be widowed, or to be a mature single woman. Even then, legally, a single woman or a widow needed the cosponsoring signature of her father, a brother, or an adult son when she was buying, selling, or exchanging property of any kind.

Dallas looked male and felt male. Banks, law firms, city offices, publishing companies, retail stores, churches, schools-everything-had a man at the top who was supported by women in his life-his wife, his mother, and his private secretary. The more important his position, the more women there were in his support network.

In practice, women usually behaved as if they were grown-up, independent people and got by with it. They never knew they were objects of abject discrimination until they ran blindly into legal walls. It happened to my mother in 1931. I’ll never forget her indignation as she marched up the front porch steps removing the pins that held her felt cloche in place. She and Dad were returning from the county courthouse where they had gone to sign over the deed to property they had worked together to acquire. Mother had been taken aside by an indulgent clerk who had explained to her that her signature was not required. Legally, she was a non-person.

I was a bride in 1946 when I learned that I, too, didn’t count. For two years after graduating from college I had struggled to establish myself as a responsible career person, and I was tremendously proud of the credit cards that had been issued in my name. When I married I called the credit department of Neiman-Marcus and requested a new card with my new name. They were very polite. They would send me a new application. I learned, that must be signed by my husband. What it meant was that I could no longer be responsible for my own debts, even though I was still working at the job I held when the original application was approved and had, in fact, recently had a promotion. My new husband, recently discharged from the Marine Corps, had no credit rating at all.

My stories, humiliating as they were, are nothing compared to the hundreds I heard as a reporter for the Dallas Times Herald from 1957-1984 and during public hearings as a member of the Dallas Commission on the Status of Women. A lovely silver-haired widow explained that she had handled all of the family business and paid all of the family bills throughout her marriage only to learn that she had no credit rating at all when her husband died. “It’s as though I didn’t ever exist,” she said.

Another single career woman who had supported both of her parents for a number of years before her mother died applied for a loan to buy a new car. The bank would be glad to give her the loan provided her father cosigned the application; she made a trip to the nursing home to get his signature.

Though inequality permeated women’s lives, it was not a topic discussed in public. That is what the symposium changed. For the first time, in an organized manner, Dallas women explored the voids in their lives and admitted to each other their pain and their frustration. To be sure, all of this was in a ladylike manner in an academic setting and at a time when the women’s movement, in much more radical forms, was filtering into national consciousness. Across the country young women and older college-educated women were verbally revolting against bondage.

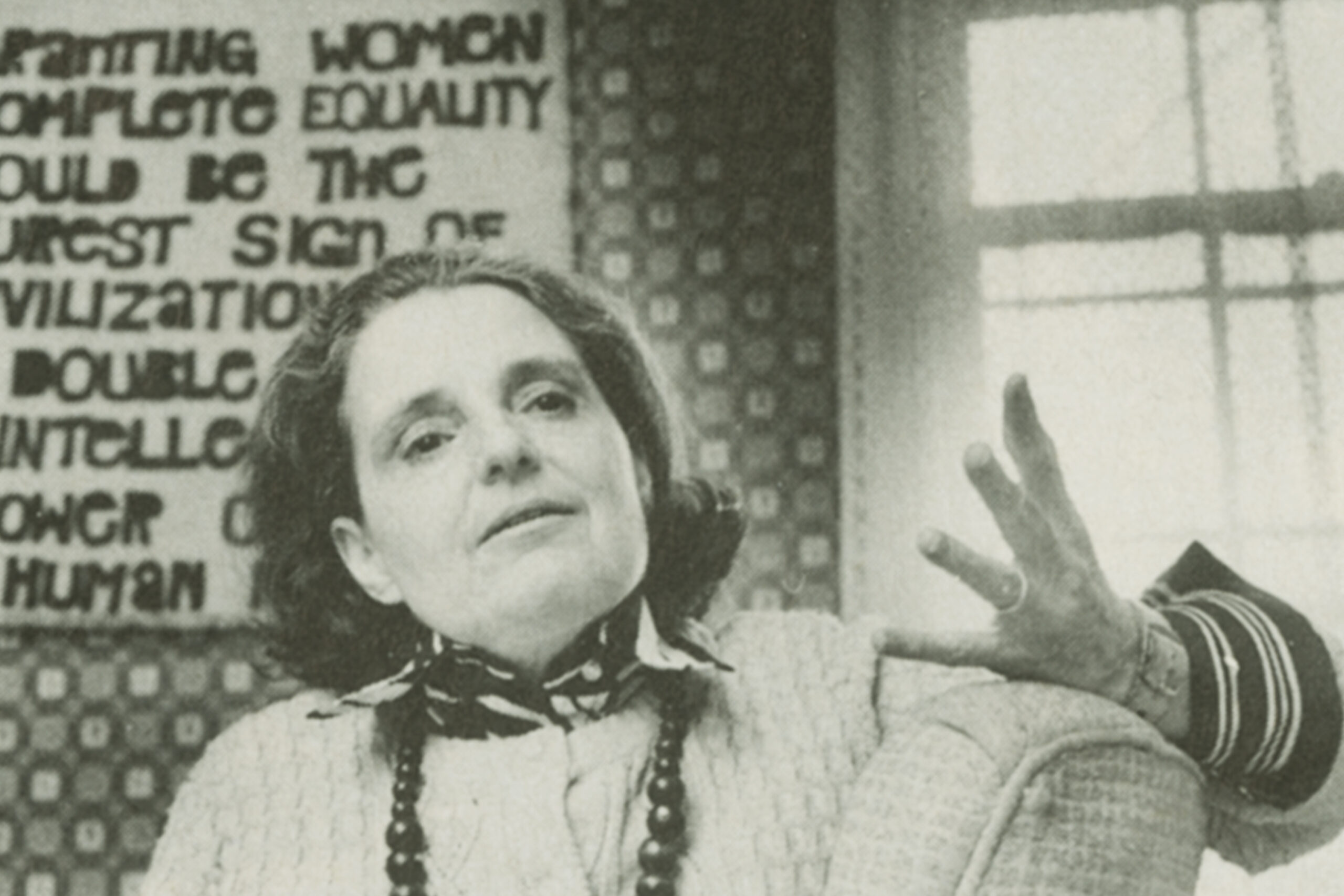

Three years before, in 1963, Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique had kicked off the women’s movement in America. By first probing into her own lack of fulfillment as a wife and mother of three children, and then through in-depth interviews with other women about their intimate lives, Friedan unearthed vast discrepancies between the picture-perfect image of every woman as a happy homemaker and the reality of the individual “who does not know who she is.”

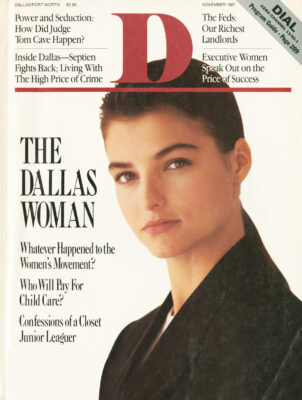

The book was not long off the press when Friedan came to Dallas for two speeches. On the night of her arrival she spoke to students at SMU; young Dallas women packed the auditorium and gave her a rousing standing ovation when she finished. The next day Friedan went to Temple Emanu-El, where her considerably toned-down address left her affluent middle-aged audience in a quandary. Sparse, polite applause greeted the conclusion of her address. The women who had spent their entire lives married to perfect men, running perfect homes, and preparing perfect children for Harvard or one of the Seven Sister schools were not prepared to have the way they lived their lives called into question.

There was a revolution brewing in other parts of the country, and a series of changing laws in the decade 1964-75. The women’s movement changed the laws and the laws changed the women’s movement. The Equal Pay Act that went into effect June 11, 1964. and was amended in July of 1972 decreed equal pay for equal work; Title VII prohibited employment discrimination on the basis of sex, race, color, religion, and national origin; Title IX extended equality of work opportunity in educational institutions; the Fair Housing Act, 1968, made it illegal to discriminate on the basis of sex for federally guaranteed loans; and the Equal Credit Opportunity Act, 1975, guaranteed equal credit to women. These laws were enhanced by a number of executive orders through the years.

The laws were in place and the women were at work, but sometimes Dallas did not get the message. Both Southern-where the ideal woman was a helpless Magnolia-sweet maiden-and Texan-where the male model was wild, Western, and macho-Dallas, Texas, did not provide the best of all possible places for rebellion.

But there had always been trailblazers, those “uppity wimmin” who didn’t know their place and were ahead of their time. Women like:

- Judge Sarah T. Hughes, who first ran for public office in 1930 and was elected ten of the twelve times she ran before being appointed a district judge over the opposition of State Sen. Claude Westerfeld because she was a woman and “a woman should be home washing dishes.” Hughes practiced what she preached to other women. She persisted in advancing her career until her friend Lyndon Johnson appointed her to a federal judgeship.

- Adlene Harrison, who made it clear that she took her responsibilities on the CityPlan Commission seriously and that those responsibilities did not include bringing cookies to meetings. Later, as interim mayor of Dallas in 1976, she retained her poise when a disgruntled speaker turned loose a shoe box full of roaches to demonstrate the deplorable conditions in public housing.

- Louise Raggio, who in 1955 became thefirst woman district attorney hired by HenryWade-over the objections of another attorney who declared that he always putwomen on a pedestal and it was hard to keepa woman on a pedestal who was opposinghim in a courtroom.

- Hermine Tobolowsky, who endured years of insults from state legislators and other unenlightened individuals in her continuing campaign to add an equal right samendment to the Texas constitution.

- Willie Newbury Lewis, who tossed down her cards at the Dallas Woman’s Cluband announced to her bridge partners that”well-off women ought not to be wasting ourtime this way. We need to be doing something for the less fortunate.” She and four of her friends-Katherine McLauren Callaway, Betty Moore Chambers, Louise Snow Phinney, and Mary Batts Aldredge-then went out and organized the Women’s Council ofDallas County, a group dedicated to educational and civic endeavors to improve the welfare of Dallasites.

- Elizabeth Blessing, who in 1965 became the first woman to run for mayor of Dallas.Her candidacy for her first race to the city council in 1959 drew this headline: “Mother of 4 Asks Place on Council.” When she ran for reelection four years later, she was described as “perhaps the most outspoken member of the council.”

- Adelfa Callejo, who offered her services free to Dallas Legal Aid shortly after shepassed the bar in 1961 because, she said, “I felt many Mexican-Americans needed someone bilingual to help them.” She was turned down because she was a woman.

In groups, too, Dallas women found strength and purpose: the Business and Professional Women’s Club, the League of Women Voters, Church Women United, the Dallas Times Herald’s Homemaker Panel (later, the Women’s Panel), and the Panel of American Women.

In those dawning days of the women’s movement, only three kinds of women worked: single women who were biding their time until Mr. Right came along and rescued them; women forced by economic necessity to earn a paycheck, who often resented it and carped about the injustices of life; and the rest of us, the handful who chose careers instead of, or in addition to, husbands and children. We had come of age during World War II, had savored independence, and had refused to go back to the kitchen again even when the popular press was admonishing us to find total fulfillment within the four walls of our homes. We were out of step with our times and scapegoats for all of the world’s ills-divorce, depression, and delinquency. (Now the pendulum has swung to the opposite extreme: the woman who chooses a career in the home rather than in the workplace is made to feel inadequate. Society loosened one set of boundaries on women’s lives and imposed another. Freedom of choice is still an idle promise.)

We had come of age during World War II, had savored independence, and had refused to go back to the kitchen.

And, so, it took a while in Dallas for the women’s movement to move. SMU’s symposium, in the words of Ann Chud, was ’’a once-a-year intellectual feast. The rest of the time women live on a mental diet of bread and water.”

In search of a way to expand the once-a-year banquet and to include more women at the tables, we decided to organize. Dallas women always organize when they encounter an unmet need. They do not join a club already in existence because those are judged not for what they have accomplished, but for what is still left undone, and each woman, coming into consciousness, is convinced that her agenda will soon make things perfect for everybody.

So it was that in the fall of 1970 a small group invited Hughes to lunch at the Dallas Press Club in the old Baker Hotel. We outlined our ideas and waited for her enthusiastic offer to help. Instead she told us, “My sympathies are with you, but I am not going to do this. I have worked all of my life for women’s rights and I’m tired. If you do it, I will support you, but if you want it done, you must do it yourselves.”

It was fortunate for the women yet to grow up in Dallas that in another setting a similar idea was brewing. Jean Swenson had moved to the city in 1968 from Washington, DC., bringing with her a model for a course to support women who wanted to take responsibility for their own lives. With a core group-Jeanette Ivy and Gail Smith, soon joined by Fran McElvaney and Mary Margaret Edmundson-Swenson fashioned an eight-week program to help women determine who they were, what they wanted to do with their lives, and how to do it. The course was called Explore and was taught entirely by volunteers.

Explore is still going strong and still is directed and taught by volunteers who have gone through the course and have had extensive evaluations and leadership training. Its current director. Sue Parma, says that at least 4,000 women have Explored their lives in the last nineteen years.

Gail Smith, the only one of its founders who still lives in Dallas, describes herself as a microcosm of the young women of 1968. She spent her time looking after two small children, teaching Sunday school, doing artsy-craftsy things, and wondering why she was depressed. To do research for the Explore course, she drove herself for the first time downtown to the library.

Its founders were astonished at the impact of Explore. After an announcement in the newspaper, “our phones didn’t stop ringing for three days,” Smith says. “It was as if every woman in Dallas wanted to enroll.”

They were also shocked to learn that in some circles they were seen as subversive. “We learned we were checked out to determine if we were a part of the left-wing movement,” Smith remembers. “We didn’t know how radical we were.

“I’m amazed at its staying power,” Smith says of Explore. “So many women have been sensitized to expanded possibilities for their talents.” She is one who was. After teaching and coordinating Explore, she returned to graduate school, completed her master’s degree, and is now with the Dallas Independent School District’s department of research and evaluation.

The next step in the women’s movement in Dallas was to create a place-both a physical location and a philosophical base-where women in the embryonic stages of emancipation could meet. Such a center had always been among the goals of both the SMU symposium and Explore. Thus, it was a natural evolvement that “graduates” of both formed the core of the fifteen women who met in Ann Child’s living room in June of 1971 to form Women for Change Inc.

Maura McNiel was unanimously chosen to chair the fledgling organization. “I was the only one in the room not working or going to school,” she remembers. “Judge Hughes said I should do it!” She also remembers that somebody handed Sandy Tinkham a pencil and she became secretary. Later that summer, on August 17, 1971, sixty women crowded into McNiel’s North Dallas home to determine procedure and set strategy for Women for Change.

The ballroom of SMU’s student center was full on Saturday, October 16, 1971, when Hughes, delivering the keynote address at the first meeting of Women for Change, was repeatedly interrupted with applause.

“Women have been too satisfied with their assigned roles, too humble about their abilities for too long,” she said. “Women have been raised to get married and have babies and nothing more. Fifty years ago a woman who chose homemaking had a lifetime career. Today she has half of her life ahead after the children are grown. It is such a waste! We have come a long way,” she said, citing women in public office and in the professions, “but we have no cause to congratulate ourselves. I will not rest until women become first-class citizens.” She sat down to a standing ovation.

The organization mushroomed. Hundreds of volunteers flocked to participate in its nine task forces-child care, counseling, education, employment, higher education, legal, media, political, and women’s center. Hundreds of others came seeking help for every conceivable problem. Some of the stories were hilarious. Many were heartbreaking.

Through the Seventies and early Eighties the women’s movement grew as consciousness-raising groups sprang up all over the area. One group after another organized to address specific areas of concern to women. In the fifteen months following the organizational meeting of Women for Change, four groups and a number of specialized programs began:

- Women’s Equity Action League (WEAL)had its Dallas birth in July 1971 in GinnyWhitehill’s home where women met to forma state chapter of the national organization.Marsha King and Paula Latimer. both ofDallas, headed WEAL.

- The Women’s Political Caucus began inthe spring of 1972 with twenty chartermembers and Lorey Gallop as its president.

- The National Organization for Women(NOW), Dallas chapter, got started in Julyof 1972 under the guidance of Jane Baker andMarjorie Schuchat, who was also the firstpresident of the group.

- A Women’s Coalition formed in November of 1972 was established as the coordinating group for other organizationspromoting issues of special concern to andimpact on women.

The coalition was needed. Even though Women for Change, which eventually evolved into the Women’s Center of Dallas, had envisioned itself as the center for all women’s activities, other individuals and groups did not perceive it as such and did not always align themselves with it. For one thing, it was action-oriented, and many women saw it either as too mainstream on the one hand or too revolutionary on the other to fulfull their specialized agendas. The coalition still serves as an information center, a bridge, and a clearinghouse for other women’s organizations.

Neither the settled groups nor the new ones wasted time getting involved in the community.

- The SMU symposium continued tochallenge the intellectual and organizationalskills, presenting in 1971 former AttorneyGeneral Ramsey Clark for a keynote speechon “The Political Process.” The followingyear, U.S. Rep. Patsy Mink of Hawaii andABC/TV correspondent Marlene Sandersspoke on a “Kaleidoscope of Change.”

- Explore, in its third and fourth seasons,ventured beyond church settings for itsclasses, set up new task forces, and proclaimed that “both men and women…[need] new approaches to life.”

- Women for Change opened its first offices in donated space in the Zale Building.Its officers and staff spent hours workingthrough priorities.

- The Women’s Political Caucus had beenborn out of the Women for Change politicaltask force at a meeting held in the fall of 1971.Elected and appointed women officeholdersin the state, including State Rep. Frances(Sissy) Farenthold, spoke. “We didn’t haveany idea how many would come,” saysMcNiel. “1 got there early and set up fiftychairs.” More than 600 people showed up,

That meeting, among others, persuaded women that the time had come for some of them to run for public office. It was the year (1973) that Sissy Farenthold ran unsuccessfully for governor and Eddie Bernice Johnson was elected to her first term as a state representative.

Women’s Equity Action League was known by its friends as “the cutting edge of the women’s movement” and by its detractors as “a rabble-rousing troublemaker.” It filed lawsuits, among them a complaint against forty Dallas-area banks for discrimination against women in hiring and promotion. In the eighteen months between its first meeting in the summer of 1971 and December 1. 1972, WEAL filed eighty-two discrimination suits against sixty-three companies. Not everybody approached by WEAL wanted to file suit against their alleged oppressors. Sometimes the group filed suit anyway, as it did for the Dallas County women employees, who, as one reporter wrote at the time, “figuratively spit in the face of WEAL.” Marsha King took the rejection philosophically. “Some women don’t want to be rescued from the velvet ghetto,” she said.

When Women for Change was organized, its founders had considered establishing, instead of an autonomous group, a local chapter of the National Organization for Women, but we didn’t think that our city was ready to accept a NOW chapter. A year later the climate for feminism had advanced to the stage that Baker and Schuchat found no resistance to NOW. Among the charter members was Mary Esther Gaulden, a relative newcomer to Dallas who had been among the women invited to New York by Friedan in 1964 for the founding of NOW. Gaulden, who was on the research team at Oak Ridge, Tennessee, that studied the effects of manmade radiation, would later establish the first advocacy program for women at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical School.

Some women, luxuriating in their cocoons of comfort, cannot grasp limitations on others that have not touched them.

Though few in numbers, NOW made a tremendous difference in the lives of women during its first three years. It worked in employment discrimination, the Texas ERA, birth control, child care, women in poverty, health, and media.

“I consider our greatest victories getting more women visible in the media and getting changes in some of the textbooks,” says Mar-jorie Schuchat, who is now teaching at Brookhaven College. “Those were the days you never saw a woman giving the news on TV. You would see her hand on the microphone, but never her face. For a long time we worked with the management at Channel 5. Finally they said, ’Okay! Okay!’ They didn’t want us challenging their license.”

In August of 1972 when NOW members and other women activists flooded Austin to push for the Texas Equal Legal Rights Amendment, they knew that large numbers of anti-ERA women would also be present. It was easy to tell which side a woman was on. Those against were instructed to wear pink and became known as “The Pink Ladies.” Those for the amendment wore anything but pink. “It was hilarious,” Schuchat remembers. “They had thought we would be hair-pulling harridans. We didn’t know what to expect from them. It turned out we were super polite to each other, especially in the restrooms where we couldn’t help meeting. They had been trained to be ladies. We wanted to be sisters.”

NOW also wrote the proposal for the first grant to establish a rape crisis center in Dallas and lobbied it through the commissioner’s court. Until then rape was cloaked in shame and silence. In Dallas the most violent things that happen to women are so offensive that neither they nor the public will, at first, call them what they are. Assistance to rape victims, battered women, and sexually abused women was couched at first in terminology acceptable to a sensitive public. Only those closely associated with Women’s Help knew that it was a program to assist rape victims until NOW called it Dallas Women Against Rape, Later, women battered by their husbands would be assisted by the Domestic Violence Intervention Alliance; incest victims went to meetings of the Recovery Association.

And there were other signs of growing momentum. In the fall of 1972 SMU introduced its women’s studies program. “I was so impressed with the program when I arrived in 1974,” says Judy Mohraz, who came to Texas from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaigne to teach American history. “Texas was perceived as a backwater area for feminism. What I found was an excellent program of academic strength. Its faculty was entrenched in the university; there were no marginal instructors as often is the case with women’s studies.”

Gloria Steinem, one of the nation’s best known feminists, had made a similar observation when she was in Dallas for a speech on February 4, 1972. “1 am surprised,” she admitted. “You have more of real significance going on for women here than in almost any other place in the country.”

The women’s movement reached a meridian on November 8, 1972, when the state Equal Legal Rights Amendment became law one day after voters approved it by a four-to-one majority. It had come before the legislature seven times before it was passed. And early in 1973 another decision set in motion earlier by a Dallas woman rocked the nation. Its reverberations intensify with the years. On January 22, the Supreme Court ruled that abortion laws in thirty states were unconstitutional. The case had started in Dallas in December of 1970 when Linda Coffee, a twenty-nine-year-old attorney, filed a lawsuit in Dallas to test Texas abortion laws. Known as Roe v. Wade, the suit had made its way through the legal process to the highest court in the land.

“We [women’s activists groups] were looking for an appropriate plaintiff to test the Texas law,” says Coffee. “I was referred to Jane Roe through an attorney friend who was handling an adoption for her.” Jane Roe later revealed her identity as Norma McCorvey, a twenty-five-year-old unmarried woman who was pregnant, she said, as a result of being raped by three men while on her way home from work. (This year, McCorvey admitted lying about the rape.)

Coffee filed the suit and called her law school friend, Sarah Weddington, who became co-counsel handling the case. “We didn’t dream that our case would be the one to go to the Supreme Court,” says Coffee. “Nor could we imagine that now, fourteen years later, the issue would still be very much in the headlines. It was a very satisfying experience for me personally. As a feminist, I consider a woman’s right to control her own body an essential first step to her being able to control her life.”

In 1973, Marsha Richardson, twenty-two, had gone to work for the Dallas County Sheriff’s Department. When she was passed over several times for promotions, she filed a discrimination charge against the department with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. Subsequently she resigned but did not drop her complaint. “I don’t know anyone who has successfully stayed with a company after bringing a suit,” says attorney Coffee. “Some stick it out, but it’s very difficult.”

In 1982 Richardson, who had later been joined in the suit by other women, won a judgment in federal court, The Sheriffs Department appealed to the Supreme Court, which refused to hear the case and remanded it to the 5th Circuit Court of Appeals, which ruled in Richardson’s favor. Richardson’s total remuneration was $1,347.50. “I don’t know how I feel about it,” she said shortly after the judgment. “It has taken ten years of my life. I have no job. It almost wrecked me.”

By 1974 women’s social, health, employment, legal, and political needs were being addressed-if certainly not yet solved. But women were lagging far behind in money matters. Many were in a Catch-22 situation. They could not establish a credit rating without having successfully borrowed and repaid a loan and they could not get a loan without a credit rating.

In Dallas, a special meeting with representatives from many women’s organizations was called to discuss the dilemma. In this, as in all the other groups, those initiating and leading the program were women with proven track records. They had already learned how to work within the system and how to work the system and change it. The first idea was to have a women’s bank. When research proved this untenable, they turned, their attention to a credit union. Under the leadership of Vicki Downing, they established the Women’s Southwest Federal Credit Union, chartered in 1974, the second credit union for women in the nation and the oldest surviving one.

The credit union began slowly but has grown steadily through the years, lending $1,678,000 with an overall loss of 1 percent. For the month ending June 30, 1987, it posted a delinquency rate of just 0.3 percent.

“Our clientele ranges all up and down the financial scale,” says Genie Fritz, immediate past president. “’We have helped a lot of women.” When WSFCU follows its guidelines, Fritz said, it almost never runs into problems. “We do work with our clients. If a woman is in a crisis, loses her job, or has an illness, we try to help her. She always pays us back.” Some people, she says, mistakenly look on the credit union as a charitable institution. “When they cannot qualify for a loan, they are bitter.”

Those whore are successfully involved in progressive change tend to think that everybody is moving along at the same pace. It is shocking to learn that this is not true, as feminists discovered in 1975 when they held public hearings for the seven mayoral candidates. Some seemed puzzled that women thought they had special needs, Of all the candidates-there were no women-only Wes Wise said he had been approached about a commission for women and he was considering establishing one if he were elected. True to his word, Mayor Wise instituted proceedings that brought into being, in July 1975, the Dallas Commission on the Status of Women. Carolyn Galerstein chaired the group of twenty-two members, including one man, Dan Weiser.

The commission arranged a public hearing at City Hall to listen to women tell about their special needs. The first hearing, with speakers allotted five minutes each, stretched far beyond its scheduled time and a second session was scheduled. It was as if a lid had blown off Pandora’s box, as if for the first time somebody would listen to women tell their stories of limited work opportunities, deplorable child care, festering health problems, and insufficient housing.

From the first two-year-term commissioners came a study titled “Profile of the Dallas Woman.” It remains the most comprehensive mass of information ever accumulated on the special needs of Dallas women. The commission also held a Work Fair to help women acquire and/or advance in their jobs.

While the Dallas Women’s Commission was planning its work fair, a group of students at SMU were struggling to get the opportunity to work in law firms of their choice. Women often could not even get an opportunity to interview, they found.

Mannette Dodge and Charla Tindall were presidents of the SMU Association of Women Law Students when a sex discrimination suit was filed against four prominent law firms-Hewett Johnson Swanson & Barbee; Strasburger, Price, Kelton, Martin & Unis; Thompson, Knight, Simmons & Bullion; and Wynne & Jaffe. It was not an easy thing for them to do, Tindall says, because of the almost certain damage to their careers. “I knew my name would be on that litigation, and I knew my name would be mud,” she said.

Tindall served as president of the student association for two years. It was especially difficult, she said, to be called in by the dean and asked if she could not control the girls and keep them from needling those law firms. As she sees it. she had no choice. “I was an older member of the class; I had to stand up and be counted.” As a result of the case, Tindall thinks, “Change came much faster than it might.” A number of defendants settled out of court. “In the settlement process there was a real consciousness raising. Law firms started looking at what they were doing. When they say they hire the cream of the crop and seven of the top ten students are women, there is no way they can exclude women from interviewing.”

The litigation also helped to change the makeup of law classes all over the country, Now from 25 percent to 50 percent of every class is female. “Women have minimum trouble getting interviews. They are happy with the jobs they get and are allowed to do. It’s no longer an oddity for a woman to be hired and to excel. It’s almost as if no problem ever existed,” Tindall said.

The Mid- to late seventies was a period of integration for the women’s movement. Exhilarating advances were tempered by tough reverses. Equality that had seemed so fair and reasonable became complex and difficult. By the score, reflecting what was happening in the rest of the nation, Dallas women gave up. They bailed out of action or they never entered for a variety of reasons, among them disenchantment, boredom, and exhaustion. Others have been forced to make accommodations between commitment, family, and jobs. And many women who have come of age during the past decade have neither the knowledge nor the interest to struggle for their rights. They assume equality. They enter doors of opportunity already ajar. They do not know-and if you tell them they do not believe-that women still face insurmountable obstacles.

What takes a sentence in a book of record often took years to achieve. Young women cannot understand that the effort expended in the 1975 National Women’s Agenda was finally focused into a document that was signed by 102 organizations representing almost every genre of interest.

As women opened their own businesses or moved into middle and upper levels of corporate management or professional achievement , they felt a need for organized systems to aid and support them. So were born groups as disparate as Executive Women of Dallas, an openly elitist group that limits its members to one hundred and seeks those who have already achieved degrees of success; the short-lived, highly activist Women’s Law Center; the Displaced Homemaker program, helping women who had devoted their lives to homemaking careers and who, through death of the spouse, desertion, or separation, had lost their jobs; and another advocacy group founded to address the problems of women existing in the shadows of society’s taboos-battered women. Gerry Beer organized the Domestic Violence Intervention Alliance, and on February 28, 1979, opened the first shelter for battered women and their children in a renovated old house on McKinney Avenue near downtown Dallas. Called The Family Place, the home is now located on a tree-shaded lot in Oak Cliff where last year it sheltered 444 women and their children, counseled 1,992 women and 174 couples, and answered 5,175 crisis calls. Today there are four other local shelters-Genesis Women’s Shelter, operated by the Episcopal and Presbyterian churches; New Beginning Center in Garland; the Arlington Women’s Shelter; and Women’s Haven of Tarrant County. Enlarged facilities at the Salvation Army also help meet the needs of battered women.

Eighteen years after The Feminine Mystique brought women out of their kitchens and into corporate boardrooms, its author, Betty Friedan, wrote The Second Stage, a book that many feminists saw as a betrayal of the causes Friedan espoused. What really happened was that Friedan, like all mothers, had given birth to 4 “child” she could not always control. While in Dallas in 1981 she explained that the women’s movement had unleashed a profusion of great riches for : women, but that too many had exchanged one set of restrictions for another.

“In the first wave of the movement we [women] had to focus on breaking out,” she said. “In the second we focus on including in.” She did not like what she often saw happening to young women who were “investing everything in their careers and leading very narrow lives. They are emulating male power models…at the time when men are questioning their own models.”

Three other significant organizations and a program to support incest victims were yet to come in the Eighties. The first was a revival of the Women’s Political Caucus led by Harryette Ehrhardt. The former caucus, which had made such an impact in the movement’s early days, had waned when its dynamic young leaders had moved away and it had finally disbanded. |The reorganized WPC comes at a time when both major political parties are courting the women’s vote.

Even more potent is the Dallas chapter of the National Political Congress of Black Women, organized June 22, 1985. Led by DISD school board member Kathlyn Gil-liam, NPCBW aims “to, empower black women politically.” It encourages women to register and vote, searches for candidates and supports them, raises money, and supports elected officials. The organization has sixteen standing committees and is moving from the strictly political to the politic. Gilliam says the Dallas chapter, with about one hundred active members, is one of the strongest in the nation. “We have the widest spectrum of members,” she says. “Democrat and Republican. Radical to mainline. But there’s no describing the feeling of sisterhood. It’s all right not to agree. I’ve never worked with a group of people so different who cooperate so well.”

Aware of the strong growth of special interest groups among women. Gilliam thinks the trend is “positive and healthy. You first have to get your own health in order before you can form alliances with others. From strong specialized groups you build strong coalitions.”

From such specialized groups came the Dallas Women’s Foundation, suggested first by Helen Hunt Hendrix. chartered in 1985, and introduced on July 22, 1986, in the most successful intergenerational, multi-ethnic, economically inclusive program ever assembled in Dallas. At Loews Anatole Hotel, 1,700 people sat down to lunch together, heard Transportation Secretary Elizabeth Dole speak, and applauded the first grants awarded by the foundation, one of which went to the Incest Recovery Association.

Though it has slowed in the last few years, the women’s movement continues to have an impact on people’s lives. Just this past March, the Supreme Court ruled that employers may sometimes favor women and minorities over better qualified white men in hiring and promoting in order to achieve a better balance in the work force.

Not all women who have advanced into positions of importance are avowed feminists. Some deny the label while upholding the cause. Others, declared feminists, set the movement back by their abrasive styles. While many successful women have benefited by the advances of the women’s movement, they have also, by the sheer impact of their contributions, edged the movement along.

Mayor Annette Strauss is a prime example of this latter type. She gained most of her experience in volunteer work, without doubt the toughest training there is, for to be successful one must be sufficiently empathetic to relate warmly with co-workers while being organized and strong enough to produce the desired results-all of it without any financial remuneration. The mayor has mastered that ability. While she serves on the advisory boards of the Women’s Center and the Women’s Foundation, she has never been an activist for women’s causes, practicing instead an inclusiveness like Friedan called for in The Second Stage, which embraces but is not limited to women’s issues.

Many other women, working in business and professional careers and as volunteers, have made contributions to causes that have an impact on women’s lives. Women like Mary Kay Ash, founder of the multimillion-dollar cosmetics company; the late Mary Crowley, founder of Home Interiors and Gifts Inc.; the late Bette Graham, founder of Liquid Paper-all gave and received assistance to women. There are many others of note-Hortense Sanger, Betty Jo Hay, Isa-belle Collora, Yyonne Ewell, Anita Martinez, Nancy Brinker-who have contributed to the human family in special spheres.

But Dallas is also a bastion of women who are not involved in the women’s movement. Some, luxuriating in their cocoons of comfort, have no desire to be “rescued” and cannot grasp limitations on others that have not personally touched them. Some have never acknowledged that the boundaries of their lives are defined by unfair exterior forces. Some accept impediments as if they are right and natural. Many are struggling for survival and unaware (hat peripheral pressures limit their possibilities. People-men as well as women-do not become feminists without awareness that prevailing conditions are unfair and need to be changed. For most people, this comes as a crack in their individual understanding. Jane O’Reilly, writing in the premiere issue of Ms. fifteen years ago, called it the “click”-that moment of truth when a woman realizes that power and patriarchy impinge on every facet of a woman’s life. A woman’s “clicks” usually come when she is suddenly, stunningly aware that discrimination limits her personally. A man’s “click”-if it happens all all-comes when his brilliant daughter, for! whom he has just shelled out thousands of dollars in education, is offered a job and a salary inferior to that of a less qualified young man.

Dallas men, for the most part, have a difficult time with the women’s movement. They don’t understand it and they rarely put themselves in a position to try to understand it. They continue to evaluate everything by their own male standards, as James Crupi did in the spring of 1082 when, during a speech for [he Dallas Institute of Humanities and Culture, he said that minorities and women have no power in Dallas. It is surprising that so many people took him seriously. Using the typically male value system, he had measured power and value by externals-what could be counted, weighed, or measured. How much? Many? Tall? Big? Wide? What’s it worth? Measured in dollars and cents. Though Dallas women have long wielded power by the male quantity standards, they have added the far more subtle value of quality and in this way have had extensive power in shaping the city.

Dallas men rarely try to understand the women’s movement. They continue to evaluate everything by their own male standards.

Unaware of how seriously women feel about their tentative advances, men dismiss the movement-or try to-with jokes. Architect David Braden is still trying to live down his comments about achieving women that he made in 1985 at a Chamber of Commerce luncheon honoring Dallas’s Women of Achievement. Former school superintendent Nolan Estes once publicly apologized to teachers when a sexist joke he told during a speech for the opening of school was greeted by guffaws from men and stony silence from women.

Dallas is not, by far, the best place in the country for ambitious women to work, as shown in numerous surveys. Often it takes someone from another part of the country, where discrimination against women is either less or appears so, to assess the pervasive macho climate here Nancy Cronin of Cleveland, Ohio, brought it clearly into focus in March of 1984. President of the City Club of Cleveland, she was one of thirty civic leaders from that city visiting Dallas to learn what dynamics made Dallas such a progressive city. The visitors were given royal treatment by the Dallas city fathers, among them former mayor Erik Jonsson, some of whose statements were laced with inadvertent sexism, “It really shocked me,” said Cronin. “1 don’t think I could live in this city. It’s very sexist and male dominated. When I heard the first man, I thought it was just one speaker, but the sexism really ran throughout them all.”

THIS WAVE OF THE WOMEN’S MOVEMENT in the United States is approaching its quarter-century mark. If those of us who thought full equality would come quickly were mistaken; those who thought the movement would soon fade from public consciousness were even more in error.

There has been great progress. Many things that would have been unthinkable in 1963 are now accepted as normal. A woman, Sandra Day O’Connor, sits on the Supreme Court. A woman, Geraldine Ferraro, conducted a serious campaign for vice president of the United States. Annette Strauss is mayor of Dallas. Women astronauts have gone into space. Women are students in the military academies, Women anchor prime time television news. Women physicians are so well accepted-14.6 percent today as compared with 7 percent in 1970-that nobody today considers a female doctor unusual.

Most of all, public opinion has shifted. In a 1986 Gallup poll, 56 percent of the women questioned said they are feminists; only 4 percent said they were non-feminists. Almost everybody-men as well as women-subscribes to the basic tenets of the women’s movement: equal pay for equal work and a female’s right to study and compete for any job of her choice.

The best measure of any movement’s success is that people accept the given as normal. That is where the women’s movement in Dallas appears to be today. Women are in key positions, not only because they are qualified, but because they live in a day when it is possible.

In Dallas, the women’s movement has been both a part of and apart from the national movement. It has been orderly, well organized, non-confrontational, and unrelenting. “You women never give up on something you want,” Alex Bickley once said to Adlene Harrison as much in appreciation as in exasperation.

So, there is no problem, right? Wrong!

The old boys network is still solidly in control. In government, only two of our one hundred senators are female. Only two of our fifty governors are women. Only one of our nine Supreme Court justices is a woman.

The women’s movement has made a far more emphatic impact on Dallas life than is acknowledged or evident. It is not finished. Like the national movement, it is in a period of evaluation. When it moves forward, it will do so with new coalitions and new vigor.

The late Margaret Mead, in Dallas in 1977for one of her last speeches, threw out thechallenge. “We have left women in thehome,” she said, “and men in the marketplace, each isolated to the detriment of both.If the future is to be at all, it must be done byall. The day is past when women’s talentsshould be left to smolder in the isolation ofthe suburbs and men should kill themselvesin the jungles of the cities.”

Author