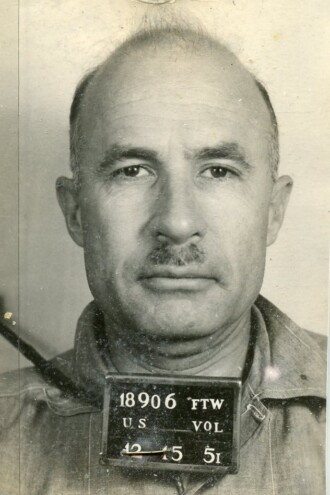

Just before Christmas 1951, Dr. Ralph Russell voluntarily checked himself into the Fort Worth Narcotic Farm to receive treatment for drug addiction. He would spend the next four months receiving treatment, getting to know his fellow federal criminal and voluntary patients, and writing letters to his family chronicling the journey.

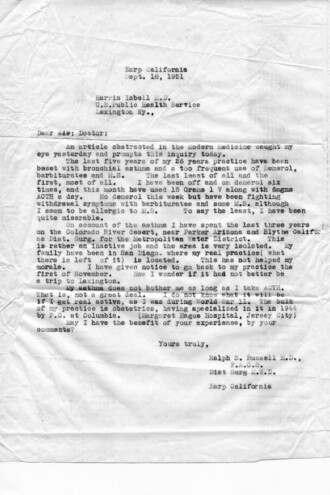

Russel had abused barbiturates for years to deal with his persistent asthma and contacted the facility to see if it might help him beat his addiction after reading an article about the facility. The Fort Worth Narcotic Farm was one of two facilities in the country that housed what was, at the time, a progressive addiction treatment. The facilities, which included voluntary patients as well as those who were sentenced there after being found guilty of drug crimes, were one of the first places that treated drug addiction as a health issue rather than a moral failing.

Established by the Narcotic Farms Act of 1929, the farms were built “for the confinement and treatment of persons addicted to the use of habit-forming narcotic drugs who have been convicted of offenses against the United States, and for other purposes.” The first farm opened in 1935 in Lexington, Kentucky. The Fort Worth farm opened three years later.

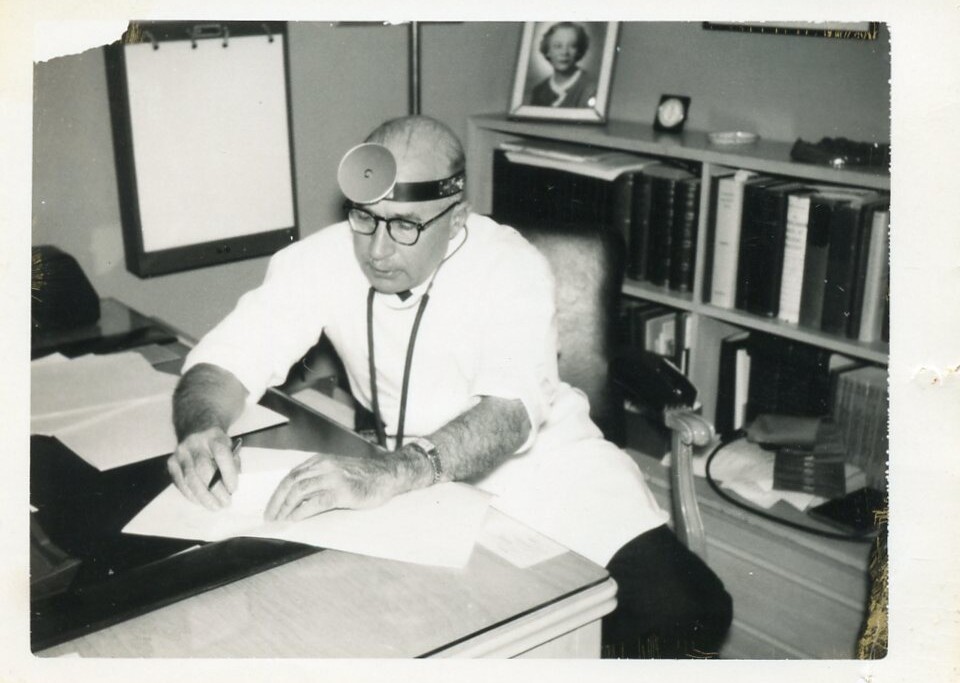

While going through some of her father’s papers, Debbie Russell found a first-person account of life at the farm in a box of dozens of letters between her grandfather, Dr. Ralph Russell, and his wife and children. Russell got to know the obstetrician grandfather she never met through the letters, which recounted his daily life at the farm, how he dealt with his other health issues, and how he made the most of his time there. She describes her investigation, how it impacted her relationship with her family, and how she redefined her life in her book, Crossing Fifty-One, which was published last year.

Life on the Farm

Ralph was living away from the family at the time he connected with the farm, allowing him to hide his drug use from his family. An article in Modern Medicine about the farm caught his eye, and he reached out to leaders at the facility and explained his issue. The facility’s leaders recommended that he be admitted voluntarily for treatment, and Ralph agreed.

At the time, the treatment was cutting-edge. Providers attempted to get to the root of addiction, addressing mental health and self-esteem issues that might push people toward narcotics. And while it was presented as a rural farm, all patients were treated like fenced in prisoners. Upon entering, every patient was strip searched, given an ID card and number, and filled out forms where they described their drug use. Next, they spent 30 days in a detoxification ward. Mail was limited and censored. The bulk of the population were people convicted of federal drug crimes.

But, at age 51, Ralph made the most of his situation and recounted his experiences through letters to his wife Ruth, his college-aged son Ralph Jr. (Debbie’s father), teenage son Bruce, and adolescent daughter Ann. The letters featured in Debbie’s book include descriptions of the physical space, daily routines, food, the weather, his recovery, and his interactions with other patients and staff.

Despite being in a locked, prison-like facility alongside criminals, Ralph maintains a positive and hopeful attitude throughout, even putting his medical skills to use on other patients. Part of the model of the narcotic farms was to provide vocational training or give jobs on the farm to the patients. As a medical doctor, Ralph was asked to assist with procedures on his fellow patients in the farm’s hospital. He would go on to assist with the treatment of several patients during his stay at the farm.

“Yesterday, I was interviewed by the chief of the educational programs. He believes the best plan for me is to assist in the clinic. Dr. Lewis is the surgeon in charge,” he wrote to his family in January 1952. “There is a doctor patient that is leaving very soon and I will take his place. He follows through on certain cases and assists in surgery.”

Technically, he could leave as a voluntary patient at any point, but the existence was closer to a prison than a modern rehabilitation center. Many of the other patients were around the same age as his sons. And Ralph, at 51, showed genuine interest in their progression and well-being.

Still, Ralph made the most of his situation. Ralph had a group of fellow inmates that he regularly counseled, calling them his patients. “They bring their problems to me and want my advice. One comes to me several times a day and wants to know if he should take the medicine that the doctors have ordered for him. I get a big kick out of encouraging him,” he wrote in a letter in January 1952.

In addition to helping with patients, Ralph’s daily schedule consisted of cleaning his room, making his bed, community work, meals, visits with social workers, leather work, time in the library, and academic classes in the education center. He also helped put together Hospital News, a paper produced by the patients.

In the end, Ralph felt optimistic about his time at the farm and seemed to enjoy the structure and purpose it provided. Despite physical health struggles, he knew he was better off at the farm than before entering. “When December started, I knew that I did not want to continue that way,” he wrote in March 1952 about his time entering the facility. “I have never regretted coming here.”

As far as Debbie knew, her grandfather never relapsed after his time at the farm from December 1951 to April 1952. He continued to be a workaholic, perhaps to keep him busy enough not to think about anything else. “He couldn’t say no when there was a patient in need,” Debbie says. He continued to struggle with his health and ultimately died prematurely of an asthma attack.

Debbie’s Journey

When Debbie found the letters in 2005, she had never heard of her grandfather’s time at the Fort Worth Narcotic Farm. The family had preserved the letters as her grandfather requested but never discussed them. This was a rare treasure for Debbie, who had long been interested in family history. Her grandfather died before she was born, but she found his personality illuminated in the letters.

“The letters themselves could be a book or a screenplay,” Debbie says. “I feel there was a narrative arc, and my grandfather is his protagonist with this problem, and he had to try to overcome it.”

But Debbie was also a full-time prosecutor, and eventually, the letters faded as a priority, and she moved to other things. It wasn’t until her father’s health began to fail that she went to him to learn more about the dozens of pristine letters, ID card, and other documents preserved in the boxes about the Narcotic Farm. The history was nearly lost forever.

As a prosecutor who saw the impacts of addiction, Debbie said there was a lot to admire about the farm’s model, especially for its time. The focus on teaching skills and giving the patients a purpose is an effective way to help them find meaning and stability after their time at the farm.

Still, patients didn’t receive enough time with providers. The lack of treatment combined with the voluntary patient’s residence alongside sentenced criminals meant that voluntary patients rarely stayed the suggested four to six months.

“That tension between the different type populations was evident,” says Oklahoma State associate professor of history Holly Karibo, who studies the Fort Worth Narcotic Farm. “The life experience of prisoner patients compared to voluntary patients was jarring and made them feel like they were a stigmatized population being housed with other prisoner inmates.”

The environment led to high recidivism rates for patients and prisoners at the respective narcotic farms. More than 50 percent of patients who had gone through the Lexington and Fort Worth hospitals later used drugs, a 1957 study found.

The Fort Worth Narcotic Farm represents a transition in the history of drug treatment, and despite its shortcomings, many of its attributes are the foundation of modern drug treatment centers. A setting connected to nature, treating addiction as an illness rather than a moral failing, and a focus on mental health rather than moral judgment are all essential parts of treatment today.

Meanwhile, Debbie’s investigation into her grandfather’s time at the facility changed her life. The title of the book, Crossing Fifty-One, references the age when Debbie started therapy and when her grandfather entered treatment. “I used my grandfather and my father as a guide to my own identity. It’s about midlife crisis and how we will get through it.”

Author