Someday, Hollywood could make a film about how Dallas came together to produce one of the most successful examples of a public-private partnership to date. After all, the story of Klyde Warren Park in downtown Dallas has all the trappings of a feel-good flick sprinkled with suspense and drama.

First there were the hard-working professionals who worked pro bono for years to bring an iconic park to their beloved city. Then came the legal team that locked in a $10 million line of credit during the height of an economic crisis. Finally, there was the out-of-thin-air stimulus money that saved the day.

Like many good movie stories, the park’s starts with a brainstorm. Then came $1 million in seed money for a feasibility study to get the ball rolling.

In 2004 The Real Estate Council, led by Linda Owen, fronted that seed money. That, in turn, led to $2.5 million in grants from Texas Capital Bank, Sheila and Jody Grant, and Crescent Real Estate Equities.

“The initial seed money was highly speculative, with no guarantees,” recalls Rob Walters, vice chairman of the Woodall Rodgers Park Foundation. “That money was absolutely crucial. It gave us the resources to get the right landscape architect and engineer to see if it was doable.”

Those moves set the wheels in motion for the $110 million-plus park atop the Woodall Rodgers Freeway overpass.

After the seed money came formation of the Woodall Rodgers Park Foundation board, a 501(c)(3) organization created to develop, operate, and maintain the park. In 2007, the board negotiated a public-private partnership with the city of Dallas and then-Mayor Laura Miller.

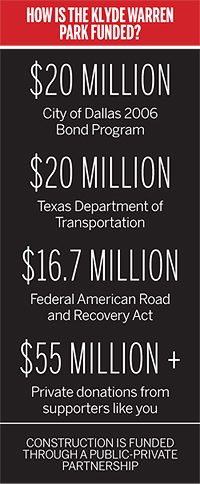

The park’s original financing concept was to raise the total money needed in thirds: one-third each from local, state, and private sources. Today, the public-private partnership stands at nearly 50 percent public/50 percent private. About $55 million has come from private donors, versus $20 million from the city of Dallas’ bond program, $20 million from the Texas Department of Transportation, and $16.7 million from the federal American Road and Recovery Act.

“The 50/50 partnership is a benefit to the public arena, because it means there is a greater contribution from the private sector,” says Walters, formerly at Vinson & Elkins and now a co-partner at Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher. “The private sector has stepped up to operate the park without public funds, but it’s a public park.”

STRONG LEADERSHIP

Dallas has had its share of successful public-private partnerships. But few, Walters says, have garnered as much unanimous support as Klyde Warren Park.

He credits strong leadership from Owen, Sheila and Jody Grant, the park foundation board—filled with a who’s who of Dallas business—and a core group of volunteer partners.

“Linda [Owen] and Jody [Grant] and their team exude so much competence and ability,” Walters says. “When we started fundraising we were way behind other projects like the Perot Museum [of Nature and Science.] But they have executed flawlessly in a short time frame.”

With such well-connected leadership, it’s not surprising they were able to call in some favors.

Bruce Gibson, former chief of staff for Lt. Gov. David Dewhurst, first heard about the park project in 2005 from Owen, a long-time friend from law school.

“She was telling me about this project and she really deeply believed in it,” says Gibson, who suggested tapping into transportation enhancement funds that might be available.

“It seemed to me that it was as important as anything in the state, because of the lack of park land in one of the premier cities in the state,” he says. “I met with the lieutenant governor and he completely agreed.”

Gibson and Dewhurst identified the project as a priority in the finance bill in 2005, and proceeded to usher it through state and federal approvals.

“It required a little political push, but it was a perfect fit” for the transportation funds, says Gibson, who served in and out of Texas government five times before landing as a principal in the Austin office of Dallas-based Ryan LLC. “To me, it was so clear that it was a great investment and a unique opportunity.”

As a result, the park foundation received $20 million from the state and federal government through the Texas Department of Transportation. The money was designated for construction of the $51 million deck park and tunnel.

LOCKING IN SUPPORT

Indeed, that $20 million was an important component in order to meet obligations under the 2006 Dallas capital bond program. In November 2006, voters approved the $1.35 billion bond program, which included $20 million for the park, with minimum matching pledges of $20 million from the private sector and $20 million from other government sources.The foundation already had raised about $12 million and was well on its way to meeting the private obligation, Walters says.

Some might wonder what it takes to be included in a bond package. The short answer: a well-conceived project with a business plan, influential backers, and some political clout.

“Lots of people want to be in a bond package,” Walter says. “It wasn’t easy, but people understood [the park’s] value instantly. Twenty million dollars of city money produced a $110 million project, so it was more than seed money. It leveraged lot of private and federal dollars that resulted in a project worth five times what the city was putting into it.”

Initial estimates showed that the park could provide a $34 million boost in annual tax revenue. At the same time, the park wouldn’t be taking a square centimeter off the tax rolls. It was actually creating land that could add value for the city and the contiguous land owners, Walter says.

As part of the public-private partnership, the city is responsible for everything below ground. The park foundation takes charge of operating and maintenance expenses, which are estimated to be $2.2 million annually.

The foundation is combining half a dozen revenue streams to pay for ongoing park operations, including restaurant proceeds, corporate sponsorships for short-term projects, ongoing contributions from land owners and contiguous neighbors, and annual fundraising, Walters says.

Foundation board member Jeffery Jackson says he’s impressed with the board’s financial acumen and conservative approach.

“The revenue from the park and restaurant will build over time, and we’ve been prudent in how we plan that,” says Jackson, the former CFO and executive vice president of Sabre Holdings. “Our $110 million goal has those reserves and more than we needed to build it. It’s a strong board with people who all have a solid financial understanding, and numbers aren’t foreign to them.”

CREDIT IN A PINCH

Linda Owen is known around town for her ability to energize and inspire civic involvement in young people. So one of her “converts,” Jackson Walker attorney Willie Hornberger, was eager to help when she called him in a pinch in mid-2008.

The deadline for a $10 million line of credit with JPMorgan Chase bank was coming due, and Owen needed his counsel to create a governance structure for the foundation and to help close the loan. Financial pledges were consistent, but the foundation needed the loan to stabilize cash flow to keep operations, design, and construction moving forward.

Normally, securing a line of credit isn’t a big deal—unless you’re in the midst of one of the worst recessions in history.

“Lehman Brothers had just declared bankruptcy, the stock market was dropping like crazy, and we were watching credit markets dry up,” Hornberger says. “Linda needed this loan to close to keep this project alive.”

Hornberger and his pro bono team worked quickly to create the governance structure required by the bank, and amended all the corporate documents needed to help raise the money through the credit line.

The loan closed in October 2008, one of the last deals to get in before banks stopped lending across the country.

“When you’re in that [economic] mess you don’t think about it,” Hornberger says. “But when I look back on it now and what was happening with the stock market, I am so grateful we got it in.”

STIMULATING STORY

U.S. Rep. Eddie Bernice Johnson, D-Texas, wasn’t surprised she was the only official from North Texas to vote for President Obama’s $700 billion stimulus plan. But when it came time to dole out the money for worthy transportation enhancement projects, she had a little fun with it.

When other Texas congressmen asked her about snagging stimulus funds for their districts, she said: “ ‘I’m checking to see who voted for this bill first.’ I told them I had to vote for it to get some.”

Johnson, who worked closely with then-Dallas Mayor Tom Leppert, originally requested $13 million in stimulus funds for the deck park, which along with much of Dallas is in her district. She upped the ante in conversations with U.S. Secretary of Transportation Ray LaHood.

“I said we could use a little more, and he thought we could find some more,” she says.

Her strategy worked. In March 2009, the federal American Recovery and Reinvestment Act awarded the foundation $16.7 million—at the time, the largest stimulus funding for an enhancement project in the state. The money arrived just in time to plug a $16.7 million funding gap for construction of the deck park and tunnel.

LaHood visited the site in November 2009 and again two years later. He said he was impressed with the number of people employed by the park’s construction.

“Dallas is such a can-do city, and there are so many examples of public-private partnerships here,” Johnson says. “I have a lot of confidence in the citizens and how they are able to achieve things. All I had to do was get the money and they took care of the beauty part of it.”

After celebrating with a party, everyone got back to work, says Tom Shelton, who helped file the application for the stimulus funds.

“We were very excited, but looked at the next milestone, which quickly became the park itself,” says Shelton, senior program manager at the North Central Texas Council of Governments.

NO FATIGUE

Dallas is known for its wealthy and generous donors, but some feared that this elite group suffered from “contribution fatigue,” after more than $300 million had been raised for Dallas’ performing arts center by 2008.

The foundation had a long way to go. But just as the stimulus money had materialized, the donors came through. Among them was Dallas energy billionaire Kelcy Warren, who paid undisclosed millions to name the 5.2-acre park after his son, Klyde.

“I’m impressed by people who are willing to donate money like this,” says Jackson, the board member. “We were raising money during a time when plenty of other organizations were seeking money. The energies and devotion of individuals on the board are a big part of the reason for success.”

Downtown Dallas Inc. was an early supporter of the park in 2005, pledging $50,000 a year for five years. John Crawford, the nonprofit’s president and CEO, says the downtown area has 15 different districts, and the park removes the perception and reality of a physical barrier separating them.

“It’s pretty obvious why we would be involved, just by looking out the window,” says Crawford from his office overlooking the new park. “We want to do everything we can to support that effort, which is going to make a huge difference in how people perceive downtown in the future.”

Although donations got off to a slower start in the conceptual phase of the park, they stepped up considerably once people could see cranes and realized that programming plans were taking shape, Jackson says.

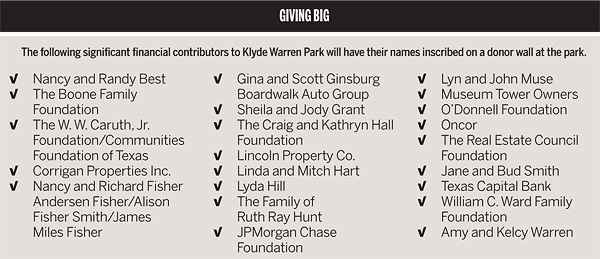

Some of the top givers are household names: Chase, The Boone Family Foundation, and the W.W. Caruth Jr. Foundation Fund of the Communities Foundation of Texas.

But there are numerous others who wanted to contribute to a piece of Dallas history in a smaller way. The “Friends” level of donors consists of up to 400 neighbors such as young professionals living in Uptown, who expect the park will be a landmark for a long time, Jackson says.

MISSING PUZZLE PIECE

Although many people think downtown Dallas doesn’t have any parks, it actually has a total of 21 green spaces. Crawford expects Klyde Warren Park will contribute to the vibrancy and revitalization of downtown, not only for the 135,000 people who work there every day, but for the families who will return on nights and weekends.

The project also has spurred surrounding real estate projects built with the intent of capitalizing on the park.

Asked where downtown Dallas would be without the $1 million seed money fronted by The Real Estate Council to explore the vision of building the new park, Crawford pauses for a long while before replying. “I can’t imagine where we would be in our revitalization without it,” he says.