Editor’s Note: This story was first published in a different era. It may contain words or themes that today we find objectionable. We nonetheless have preserved the story in our archive, without editing, to offer a clear look at this magazine’s contribution to the historical record.

The old man sat alone in his study, late into the night. George Dahl was composing a letter to his daughter, Gloria, and her husband, Judge Ted Akin. At the top, he had dated the letter April 24, 1978. It began, “I speak to you for the last time…” He finished his letter at 3 a.m. and went to bed.

The next morning, at the office of his architectural firm, George Dahl had his comptroller type up the letter. At 6 o’clock that evening, as requested by Dahl earlier in the day, Gloria Dahl Akin, Judge Ted Akin, and Laurel Akin, their 22-year-old daughter, gathered at Dahl’s apartment on Turtle Creek. He told the three of them to sit down. Then he stood and, in his small and raspy voice, he read them the letter:

I speak to you for the last time. I had hopes that you would be a joy and a source of pride and happiness to me. That is not possible now as I leave you for the last time that we see each other. You must be proud of what great irreparable damage you have done to me and Joan Renfro. You have torn asunder my hopes, you can never rise and undo your malicious justice to either of us. You have sunk to the very bottom of the heap … You all have done your dastardly damage … I had hoped you, Ted, of all people, would be fair and never engage in smear tactics and unjustifiable fabrications. Your actions do not qualify you to sit on the bench of justice. When you smeared my intended wife, you smeared me. I and Joan Ren ro have been damaged … You both speak of the fact that you are: One, watching out for my good: Two, that you love me: Three, that you are looking out for my financial affairs … These are idle words … When I question your expenditures, you say all I want is your money. What do you mean ‘your money’? … The truth is … that over $2,555,888 has been dished out to you … all through the efforts of George L. Dahl only. These financial fiascos do not ameliorate the sorrow that you have caused me by your ugly activities and your further threat of a lawsuit … You have ruined my life, my heart is heavy. Instead of being a blessing, you all have become a curse. As for the future, I shall attempt to live out my life in sorrow and sadness and shall plan for other things in the future. Remember, be honorable, just and fair … You all need guidance and counseling and now you can live without me. I regretfully say good-bye.”

The reading lasted only three minutes. The Akins were stunned. Without speaking, they took the letter from his hands and walked out.

Two days later, early in the morning, George Dahl was alone in his apartment, readying himself for work, when the telephone rang. It was the doorman downstairs calling to tell him that there were two gentlemen waiting to see him. Dahl took the elevator down and walked into the lobby. Two men in suits approached. “Mr. George Dahl?” they inquired. “Yes,” he replied. “We’re here to serve a warrant, sir,” they said, “You’ll have to come with us. We’re going to take you to the hospital.”

George Dahl was confused and frightened. When he was admitted to the psychiatric ward at Presbyterian Hospital, he was only partially aware of what was happening. This, he knew in a rush of anger and frustration, was Gloria’s work. Ted and Gloria had put him here. But to what end? Were they, God forbid, going to have him put away? Or was he indeed already put away? Nobody had told him anything. Finally, in the afternoon, he was contacted by his lawyer, who had learned of the arrest from the worried apartment manager. His lawyer tried to explain the situation: A temporary guardianship order had been served; he was being held in the hospital for mental examination. The next day, a sheriff’s deputy visited his room and officially served the guardianship order. He was now a ward of his daughter, Gloria Akin.

During the next 16 days, George Dahl was visited and questioned by three different psychiatrists. He was given tranquilizers to relax his nerves. He was subjected to a painful bone marrow test. Blood samples were taken repeatedly. He was given an electroencephalogram.

On Thursday, May 11, in his hospital bed, George Dahl celebrated his 84th birthday.

Young George Dahl, with his lovely wife Lillie, his childhood sweetheart, arrived in Dallas in 1926. The only child of Norwegian immigrants, his father a Minnesota blacksmith, George Dahl had blazed through a brilliant academic career in the study of architecture, culminating in a Harvard master’s cum laude and a Robertson Fellowship in Europe. He had worked for the prestigious Los Angeles firm of Myron Hunt before being lured to the Texas prairie by Dallas architect Herbert M. Greene.

Today, one can hardly turn a street corner in Dallas without being faced with evidence of George Dahl’s work. His career has touched upon every conceivable kind of architectural project. Some 3,000 different projects, in fact, worth $3 billion: Methodist Hospital, Mrs. Baird’s Bakery, Sears on Ross Avenue, Lakewood Baptist Church, Fair Park, Ursuline Academy, Titche’s downtown, the Dallas News building, the Earle Cabell Federal Building, the Dallas Public Library downtown, the Dallas Public Health Center, the Employer’s Insurance Building, Rusk Junior High School, Jesuit High School, Rogers Electric building, Owen Arts Center at SMU, LTV Aerospace Center, Hart bowling alley, First National Bank, the Chi Omega house at SMU, Neiman-Marcus downtown, the Park Cities Bank, Dal-Rich Shopping Center, Dallas Memorial Auditorium.

Almost every county in Texas has a sample of his craft, from Central Elementary School in Texarkana to the El Paso National Bank. Much of the University of Texas at Austin, including the landmark library, is the work of Dahl. His firm was the first in Dallas to do extensive work on a national scale, including buildings for General Motors from Portland, Oregon, to Jacksonville, Florida. RFK Stadium in Washington, D.C., is the work of George Dahl.

His firm, at its peak the city’s largest, has been referred to as “Mr. Dahl’s Finishing School,” having spawned many of Dallas’ most prominent architects whose own firms now dominate the local trade — names like Harwood K. Smith, Harris Kemp, Gordon Sibeck, Donald Jarvis, Dave Braden, and Terrell Harper. By the time of his retirement, George Dahl was worth $5 million.

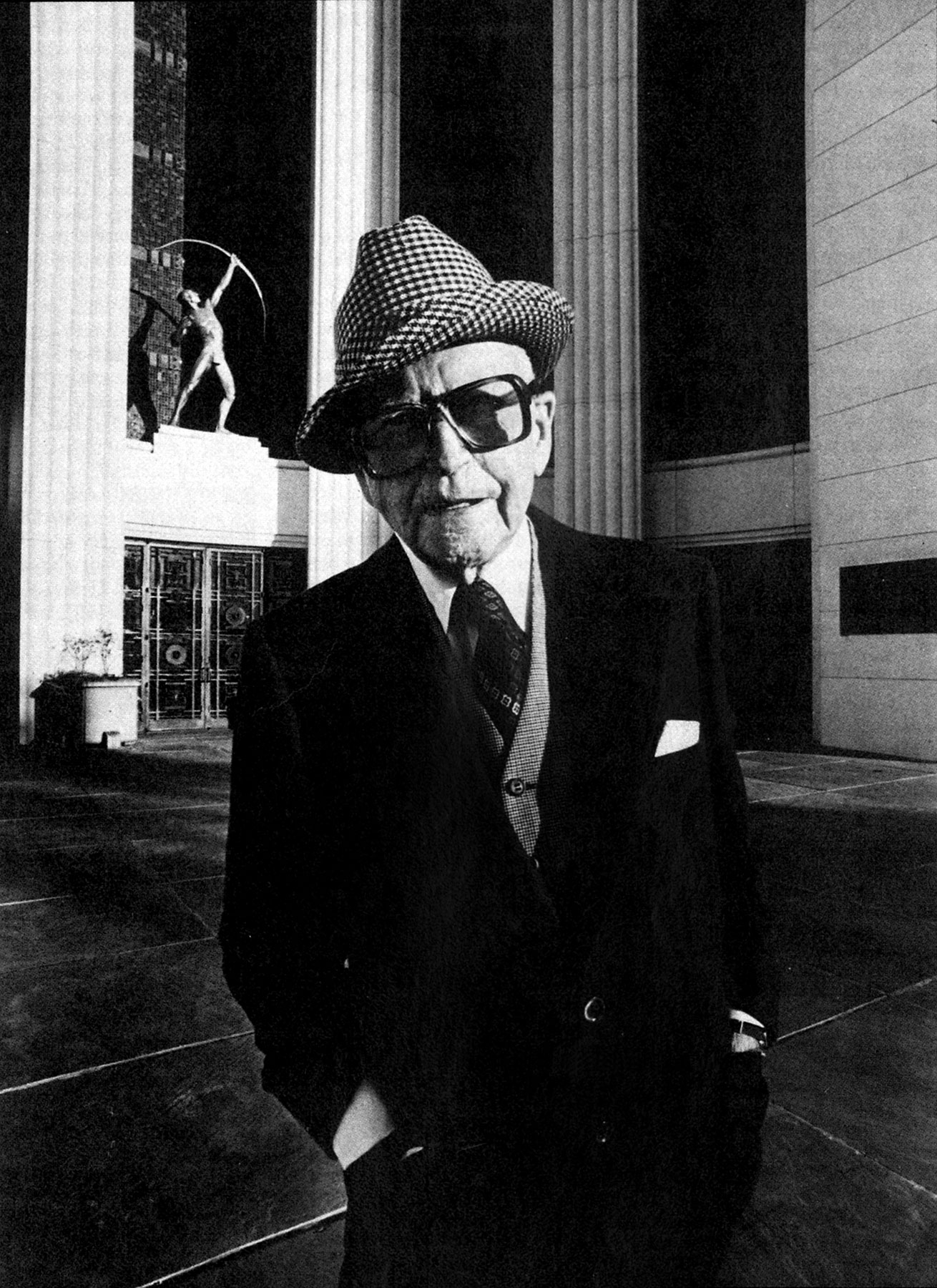

George and Lillie Dahl had always lived in style. They made a lovely couple: She was shy, pretty, gracious, elegant, literary; he was gregarious, clever, gallant, with a ribald sense of humor. Together they threw grand parties; those who were there remember them as “fabulous affairs.” They were generous supporters of charitable foundations, and of the Dallas Civic Opera. They traveled widely. George became an avid collector, a spontaneous and whimsical buyer — medieval weapons, strange musical instruments, Oriental statues, whatever caught his fancy. Once, when he admired a room display in Bloomingdale’s, full of furniture and trinketry, he bought the entire room for $10,000. His office wall is adorned with an extraordinary collection of masks; outside the door to his apartment, in the hallway, sits a large stone lion under a portrait of Napoleon. The mildly eccentric streak of George Dahl was emblematic in his personal trademark — he always wore his hat with the brim rolled down on the side.

The couple had reached the age of 40 still childless, but in 1934 they became parents of a daughter. George called it “a glorious event,” and she was named Gloria. The Dahls hired a live-in housekeeper before Gloria’s birth, a gentle black woman named Clara Thomas. Clara quickly became one of the family. They were a close family, and Gloria was a dutiful daughter. She grew into an attractive young woman.

As a student at SMU, Gloria found herself on a blind date one evening with a fellow student, a young man named Ted Akin. The attraction was mutual, and a four-year courtship ensued. Ted visited often at the Dahl house. George and Lillie liked the young man; Ted was similarly impressed, an immediate fan of the magnetic George Dahl. In December of 1954, while Ted was finishing law school at SMU, he and Gloria were married. George, in his style, provided a lavish wedding and reception.

In 1955, Ted graduated, entered the Air Force, and was shipped to a remote base in Wyoming. George Dahl decided the quarters provided for the young Akins were not suitable for his daughter, and would certainly not be suitable tor his grandchild; he bought them a house. Shortly thereafter, the Akins’ first child was born, a girl whom they named Laurel.

His daughter was happily married, and he was a proud grandfather; life was better than ever for George Dahl. Then, in 1957, Lillie Dahl returned from a routine medical examination. The diagnosis was cancer. Two and a half months later, she died.

George Dahl was staggered. Life without Lillie was something he had never tried to comprehend. Fortunately, Ted and Gloria had returned to Dallas. Ted worked briefly for Dahl before setting up a private law practice. Gloria, meanwhile, took it upon herself to care for her father in the absence of her mother. Clara Thomas was still there to see to Dahl’s daily needs, but it was Gloria who called him every day; several times a week she would visit him; almost every Sunday Dahl would join the Akin family for dinner. George Dahl instructed his secretary, “Whenever my family calls, you always be sure, no matter what I’m doing, let me speak to them.”

A second child was born to Ted and Gloria, a son; he was named George Leighton Dahl Akin because, they said, Dahl had always wanted a son. Later, a second daughter, Adrienne, was born. George Dahl often took Ted with him on business trips, introducing him to various important people. Ted appreciated the attention and looked on Dahl as “a second father.” Ted’s own career blossomed, and in December of 1963, he was appointed first judge of County Court No. 4.

Early in 1965, Dahl’s longstanding generosity toward his daughter and her family climaxed in a birthday gift for Gloria — the family home, the lovely North Dallas house he had built for Lillie back in 1941. Dahl had just completed construction of a luxury apartment building on Turtle Creek, the Gold Crest, and had decided to move into it. The family house was wasted space for him; he wanted the Akins to have it.

In the wake of his wife’s death, Dahl had not become a recluse. On the contrary, the wealthy and charming George had become something of a heartthrob for the wealthy older widows of the city. He remarked to a friend one evening at a a cocktail party, “These widows are wearing me out.” He became quite close with one long-time acquaintance, a widow named Ivy Rabinowitz, whose husband, Meyer Rabinowitz, had been a friend and business associate of Dahl’s. George and Ivy dated often, attended the opera together, dined together. At the same time, Dahl had become an increasingly active member of the Rotary Club, attending the weekly meetings with regularity. There, in 1964, he became acquainted with a younger woman named Joan Renfro, the Rotary Club’s executive secretary.

Late in 1965, at the age of 71, George Dahl went to Gloria and told her that he and Ivy Rabinowitz were contemplating marriage. Gloria was fond of Ivy Rabinowitz, but she balked. She had heard — she thought from her father — that Mrs. Rabinowitz was in the midst of some legal difficulties with her children regarding the distribution of her husband’s estate. Gloria told her father she didn’t want him to get involved in another family’s problems. She was also disturbed by the fact that Mrs. Rabinowitz was Jewish. “I’ll admit,” she said later, “I was a little selfish, too. I loved him very dearly and wanted to take care of him.” Ted Akin, for his part, thought the marriage idea a good one — he even offered to perform the ceremony. But Gloria’s dissuasion apparently had its effect. “Oh, Daddy, Daddy,” she said. “Please don’t.” George Dahl decided not to marry Ivy Rabinowitz.

Dahl didn’t seem to resent his daughter’s resistance. A few weeks later, just after Christmas of 1965, he took Gloria and Ted on a vacation trip to Mexico City. They had a wonderful time. It was perhaps the last time of untainted pleasure this troubled family shared.

In 1966, age had made little headway with George Dahl; his mind, at 72, was as acute and expansive as it had always been. He figured to be a long-liver; both his parents had lived into their 90s. Friends and employees marveled quietly at his unflagging energy, at the precision of his wit, at the exuberance of his style. His daily life was that of a man 20 years younger.

Except for a neurological pain in his left ear, and some apparently related seizures, which had required ear surgery back in the ’40s, Dahl had experienced a minimum of serious health problems. Ill-health, in fact, had always seemed somewhat shameful to him; he had a tendency to downplay any ailments. In 1966, though, he suffered what was apparently a minor stroke. His personal physician, Dr. Haynes Harvill, knowing Dahl’s attitude about infirmity, never spoke the term “stroke” to him, but the result was obvious: a minor paralysis in his left leg, which caused him to drag it slightly as he walked (he still likes to pass it off as a “charley horse”). It was the first intrusion of age, and George Dahl didn’t like it.

Anyone can suddenly find himself confined to a psychiatric ward. The person subjected to a mental illness inquiry has fewer rights than an accused felon.

But his health nagged him less than something else as he moved through his 70s: his money. Not that there wasn’t enough of it — he was still making plenty; when his firm undertook the lucrative LTV Aerospace Center in Grand Prairie in 1967, his staff peaked at 185, huge for an architectural firm. From that point, the company workload began to slacken; still, Dahl held to his longstanding policy of not taking on partners — he preferred to take the ultimate responsibility for all jobs; the company was built on that basis. He was content to wind down gradually. But the fortune he had already made began to cause troubles.

Shortly before the death of Lillie Dahl, her will was revised to establish the Lillie E. Dahl Trust. For tax purposes and for future security, a substantial portion of the Dahl assets, essentially Lillie’s half of their community property, was placed in the trust, with George Dahl as sole trustee. The beneficiaries were Gloria and her children. All distribution of money was controlled by the trustee, George Dahl. Through the years, the trust grew, and Dahl was generous to his daughter. When Gloria had substantial bills, she would submit them to her father; he paid them to the penny. When pinched times arose for the Akins, he would help them out. When it was time to provide for the education of the Akin children, he provided. And always there were gifts, at birthdays, at Christmas — generous gifts.

But in 1967, there was some haggling between the Akins and Dahl over the distribution of funds from the Ra-Dahl Corporation, a joint venture established by Meyer Rabinowitz and George Dahl with investment money taken from the Lillie Dahl trust. Gloria, as beneficiary of the trust, sought payment of $283,000 due her from Ra-Dahl. George Dahl was reluctant to make the distribution at that time. Gloria and Ted became more forceful in their request. It was not until late in 1969, almost two years later, that Gloria got her money. There were ill feelings.

In 1969, Ted Akin relinquished his judgeship to return to private practice. But things didn’t go well financially; in his income tax statement for 1970, Ted declared a net loss of $24,000. In the late ’60s, Ted Akin became impressed by a young company called Telectronics Industries, and discussed investment possibilities with Dahl. Ted and Gloria invested a quarter of a million dollars in Telectronics; George invested additional funds from the trust. Telectronics bottomed out, and they lost it all. Ted also closed down a company called Tampsco Inc. at a loss. Not all of his investments were failures — Hargrove Electronics proved quite successful — but the net result was mild financial animosity between Ted Akin and George Dahl. George became skeptical of Ted’s business judgment; Ted began to resent Mr. Dahl’s tightening control on the trust. Ted decided to close up shop on his legal practice and return to the bench; in November of 1972 he won election as judge of the 95th District Court. George assisted with the campaign. The peace was brief.

In 1973, Ted and Gloria first began raising serious complaints about Dahl’s trusteeship. On several occasions, Dahl had made distributions of funds from the trusts to the names of Gloria and two of the children, Laurel and George. He would then borrow that money back from them, giving them notes for the amount borrowed (the circuitous route was used, legally, because Dahl, as sole trustee of an irrevocable trust, could not pay funds directly to himself). The notes eventually amounted to $350,000. The Akins began complaining on two counts: One, Mr. Dahl had not been paying them interest on the notes; and two, the Akins were paying the income tax on the money extracted in their names. George Dahl resented the implications. In his mind, all the money was his money; there would have been no trust at all had it not been for his toil. The Akins’ complaints struck him as avaricious, ungrateful, and unsavory.

The Akins were more than a little disturbed with Dahl. He was, they felt, becoming increasingly difficult to deal with. He was, they thought, changing.

At the age of 78, George Dahl decided it was time to get out of the business of architecture. In August of 1973, he effected a merger with two younger firms, and the new firm of Dahl, Braden, Chapman & Jones was born. Dahl was to serve primarily as a consultant; George Dahl Inc. existed as a separate entity to finish up a few dangling projects and oversee a few investments. But his architectural endeavor would be minimal, as established by a noncompetition agreement between George Dahl Inc. and the new firm. The builder of 3,000 buildings would put away his tools and attend to the business of graceful retirement.

Dahl’s social life had for several years been centered on the Dallas Rotary Club. Over the years he had struck up a friendship with Joan Renfro, the club’s executive secretary. One evening in 1975, much more as a matter of circumstance than romance, Dahl escorted Mrs. Renfro to dinner at Chablis. They thoroughly enjoyed each other’s company, and their long relationship suddenly became a much closer one. Joan Renfro was 28 years younger than George Dahl, but she could hardly be called a femme fatale. A quiet, gracious woman with a somewhat portly figure and a ready smile, Mrs. Renfro had been divorced 15 years before, and had spent most of those 15 years in work for the Rotary Club. Over the course of the next year, George and Joan went together to fancy restaurants, the opera, art exhibits, small parties with friends. By the fall of 1976, they began talking, if only casually, of marriage.

On Christmas Day of 1976, the Akin family planned to have a holiday dinner at Dahl’s apartment. But that morning, Gloria learned there would be an additional guest at the table: Joan Renfro. Gloria was shocked. From the beginning, Gloria and Ted disapproved of the relationship between George and Joan. That summer, Gloria had encountered Joan for the first time in the lobby of St. Paul Hospital, where George was undergoing minor treatment. Gloria made her message to Joan clear: Stay away from my father; you only want his money.

Otherwise, the Akins had never really met Joan Renfro, and they were not eager to. It seemed clear to them that a 54-year-old woman, any 54-year-old woman, could only be interested in a wealthy 82-year-old man for one reason: his money. George, they were sure, was being taken in by a young and crafty secretary. The Akins had indicated their disapproval to George, mostly by showing a lack of interest when he would mention Joan to them. They had hoped he would come to his senses.

But now, on Christmas Day, Ted and Gloria talked it over and made a firm decision. They called Dahl and told him that the Akin family would not be joining him for Christmas dinner.

Resentment simmered on both sides. Meanwhile, Ted Akin had been elected in 1975 to associate justice of the Fifth District Court of Civil Appeals, a prestigious bench. But Judge Akin’s salary was still less than $50,000 a year, and the tax problems related to the trust had become nearly insurmountable without the cooperation of Dahl. Still, George Dahl reported to his office every morning at 9 and worked until 5; Gloria called him almost every afternoon to inquire about his health and his needs; George had dinner at the Akins’ home almost every Sunday, and maintained his fond relationship with his four grandchildren.

But the tensions could not be ignored. Dahl became increasingly distressed by the Akins’ attitude toward money and their attitude toward Joan. Late in May of 1977, he decided to try to put his distress on paper, and wrote a letter to Gloria and Ted:

I have had a feeling of great disappointment and anguish for some time. First, I have struggled with myself in that you doubt my judgment and actions. You have cast a great doubt in my mind of your fairness and the ability to seek the truth … In that your mind has been poisoned, it may be difficult for you to be fair and unselfish and forget your desire dictates. I hope that your thinking is not blinded by avarice and personal greed … I still love my family and still think that they can be fair in hope that I will not have to step out of their lives. I would like to share life happily with you, but not on your terms or actions.

Yours truly,

George Dahl.

He read the letter over; it sounded harsh. He folded it up and put it away. He thought there was still a chance for reconciliation through talk.

Gloria Akin’s worries about her father’s physical health grew into worries about his mental health. She saw signs that bothered her, signs of senility. His problem with his leg had become aggravated by age — he was occasionally unsteady; Gloria worried about his falling. Worse, he showed an increased aversion to her aid; he had always refused a cane but accepted her arm. Now he resisted that. She tried to help him walk down the driveway. “I don’t need any help,” he said, “But, Daddy, there are acorns … You’re going to stumble. Daddy, pride goeth before a fall.” He still resisted.

There were other things. She thought he showed less care with his once-impeccable attire; she’d heard Clara mention deterioration of his personal habits. She had been disturbed by reports from his office of “irascible behavior,” flares of temper, including an incident in which he began smashing Coke bottles against the wall. She worried about his driving, which had, amongst his employees, long been notoriously reckless — now it scared Gloria to death. But worst of all, she thought she felt a growing “coldness” in him; when she talked to him, she sensed he was turning her off; when she tried to hug him goodbye after Sunday dinners, she felt him withdraw.

Akin, meanwhile, wondered about Dahl’s business acumen. Dahl had decided to sell the Gold Crest, the luxury apartment building he lived in and owned, to liquidate the assets of George Dahl Inc. Despite a $2 million dollar profit on the sale that Dahl had negotiated, Akin questioned the loss of the real estate’s potential, worried about tax consequences, and was disturbed by the lack of reinvestment plans for the capital gains, especially when Dahl went off to Iran with talk of investing there. And the Akins couldn’t understand why Dahl maintained a full office staff, at a cost of $130,000 a year, when the office appeared to be generating no income.

And when George mentioned to them, almost blithely, that he and Joan were talking about getting married, the idea was met with quiet horror.

For George and Joan, the plan to marry had become a serious one. George knew the family blessing would not be easily forthcoming. He teased Joan about eloping, of going off “to Denver or somewhere,” and telling the family when they got back. She tried to be amused, but couldn’t be. She had been stung by the family’s rejection; she thought if she could just meet the Akins, visit with them, they would soften, learn to accept her. But such a meeting seemed less likely than ever now. Gloria was tugging harder and harder at her father. “Please, Daddy,” Gloria would plead, “don’t marry her; give her all the money, but don’t marry her.” George and Joan decided at least to wait until after the Christmas season, particularly as it was the debutante season, and Laurel Akin would be coming out. George Dahl threw a party for his granddaughter at Dallas Country Club; like the whole debutante process, it was expensive. Laurel’s debut cost the family somewhere between $50,000 and $70,000. But Dahl had already indicated that it would be covered by funds from the trust; in essence, he would pick up the tab. Laurel’s major party was given at Brook Hollow Golf Club; Joan Renfro had not wanted to attend, but George insisted. When George and Joan arrived at the family reception line, they were chilled by the coldest of shoulders.

For George Dahl, this was a point of crisis. He wrote a memo to the Akins, expressing his disappointment and seeking to reestablish harmony in the family. In early February, Ted Akin responded with a letter of his own:

Dear Mr. Dahl,

We have reviewed the comments in your hand-delivered memo of several weeks ago pertaining to living in harmony, and dispelling dissension. Much thought has been given this matter by Gloria and me and we have concluded that this can best be accomplished by payment of the note due, as well as the note to Laurel and by turning over control of whatever assets the children may have to us … This leads, of course, to certain bills pertaining to Laurel that need to be paid immediately, i.e. Draper and Brook Hollow. You previously indicated that these should be paid out of Laurel’s funds or by distributions. We believe, however, that Laurel’s funds should come from the note due Gloria … We shall appreciate your immediate attention to this matter so that we may make appropriate arrangements with respect to Draper, et cetera, as well as our personal tax plan. This will result in harmony in our view.

Most sincerely,

Ted

On March 1, Dahl told Gloria that he and Joan were planning to be married on April 1. In the meantime, he had discussed with Joan a pre-nuptial agreement; he had his attorney draft it, present it to Joan, and told her to take it to her own lawyers. It was, he explained, protection for both of them. In the event of his death, it would provide her with $18,000 a year for the rest of her life. It would thereby protect his estate from the entanglements of any further claims by her. It might also silence the gossips who would inevitably see Joan as a golddigger; after all, $18,000 a year was a nice stipend, but it was no fortune. For the Akins, though, the idea of any kind of pre-nuptial agreement was ominous. It reinforced their suspicions. But the wheels were set in motion. On March 17, George bought Joan a $3,700 diamond engagement ring.

With the impending marriage, Dahl informed Clara Thomas, his housekeeper for 46 years, that he would no longer be requiring her services. Clara, an opponent of the proposed marriage, indicated that she would choose not to work for him anyway if he married. A confusing episode ensued. Clara arranged, before she left, to have the family silver transferred from Dahl’s apartment to the Akin home. She claimed it had been authorized by Dahl, that in fact he had given her the key to the storage closet. Dahl ultimately accused Clara of stealing, took back the car he had given her 10 years before, and, despite her half-century of service, refused her a pension. Clara was deeply hurt. “I never thought he’d do me that way,” she said. The Akins were enraged.

On March 27, Gloria and Ted Akin called Dr. Haynes Harvill, Mr. Dahl’s personal physician for many years. They told him of their concerns over Dahl’s mental condition, of their perceptions of his erratic behavior, of his physical deterioration, of dubious business decisions, of the incident involving Clara and the silver, and of the impending marriage. They were, they said, planning to institute guardianship proceedings which would entail an inquiry into his mental status. They wanted to know if Dr. Harvill thought their intentions to be reasonable and if so, would he provide medical information to the court? Dr. Harvill agreed that an evaluation was warranted and to provide information. Two days later, Dr. Harvill was subpoenaed to testify in Probate Court in regard to the guardianship request of Gloria Akin.

The thought of taking legal action against Dahl was certainly not appealing to the Akins. But what else could they do? It was time, they reasoned, to put George Dahl in the hands of the law. The law would return him to the hands of the Akins. And all would be solved.

In the chambers of Probate Judge David Jackson, on March 29, 1978, Gloria Akin presented her case. With her were her attorney, James Hartnett, and Dr. Harvill. They presented their evidence, their various concerns over the physical and mental state of George Dahl. Judge Jackson would consider the application, but no order for guardianship was filed at that time.

George and Joan, meanwhile, had decided to postpone their wedding. Their lawyers had become tied up with the complexities of the pre-nuptial agreement, and George didn’t want to proceed without it. And the Akins’ resistance was as steadfast as ever. The timing just didn’t feel right. When the Akins learned of the postponement, there was some relief. But over the next weeks, Ted checked in with Dahl’s attorney, Sam Winstead, to keep track of the status and progress of the pre-nuptial agreement. For the time being, they made no more moves toward guardianship.

That evening at dinner in his apartment, George told Joan that he had come to a decision; he was going to have to sever relations with his family.

The resistance of Gloria and Ted to Joan Renfro affected the rest of the family, including the children. Dahl’s relationship with his grandchildren became strained. On a sunny Sunday in April, Laurel Akin visited her grandfather’s apartment. Joan Renfro was there, working in the kitchen. Laurel engaged Mrs. Renfro in conversation; it was the first time they’d met. She began asking Mrs. Renfro questions, simple questions: Where do you live? Where are you from? How many children do you have? Joan Renfro finally responded with surprise that Laurel didn’t know more about her already. Laurel took offense at the tone of the remark and launched into an accusatory challenge, charging Mrs. Renfro with victimizing her grandfather, of “brainwashing a feeble old man.” “I can see the dollar signs in your eyes,” Laurel said. “Oh, Mrs. Renfro, you certainly are some actress. This is just like a soap opera.” Laurel left; she was in tears. Joan Renfro was shattered. George Dahl was furious.

On a Monday evening, April 24, Joan and George sat down to dinner together at his apartment. George told Joan that he had come to a decision; he was going to have to sever relations with his family. “George,” said Joan, “it really isn’t necessary, and it doesn’t matter. Because I’ve come here tonight to tell you goodbye, anyway.” After dinner, Joan laid her engagement ring on his desk and left. It was then that George Dahl sat down and wrote his late night letter to the Akins: “I speak to you for the last time…”

The probate process that landed George Dahl in his hospital bed is a curious one. There are those who say the process, as established by the Texas Probate Code, may in fact be unconstitutional, that there is much potential in it for the abuse of an individual’s rights. From a layman’s point of view the process appears too easy, too swift, too arbitrary. A George Dahl or, in fact, anyone can suddenly find himself confined to a mental ward without the right of warning, without adequate provision for his defense. The subject of a guardianship proceeding or of a mental illness inquiry has fewer rights than an accused felon.

The day after George Dahl read the Akins his scathing letter, Gloria, terribly disturbed by her father’s words, engaged a second hearing with Judge Jackson to secure an order for temporary guardianship. In the probate procedure, such a guardianship application is presented ex parte, meaning that only one side, the applicant, is present. The individual in question thus has no chance to speak in his own behalf. The judge alone makes the decision; it is an awesome burden of judicial power. It is estimated that some 65 percent of such applications result in a grant of temporary guardianship, often simply “as a matter of caution.”

At the same time, Gloria Akin took her case to Mental Illness Court. In Dallas County, the Mental Illness Court is administered by the two probate judges, Jackson and Ashmore. Anyone can file an affidavit with the Mental Illness Court stating that a person is dangerous to himself and needs to be immediately restrained. If approved, again solely by the judge, a warrant for arrest can be issued. The person is apprehended and taken to the hospital for examination. The only requirement is that a physician examine the patient within 24 hours to determine whether to hold or release him. If certified as mentally ill, the patient can be held. A Protective Custody Order is then issued by the Court to retain the patient in the hospital for not more than 14 days. The Court then appoints a lawyer to advise the patient of his rights.

When Gloria Akin walked out of the courtroom that day, she had set the wheels of probate justice turning. Less than 24 hours later, the sheriff’s deputies were at George Dahl’s door, warrant in hand.

While Dahl was incarcerated, Gloria obtained a court order to enter his apartment. When the apartment manager refused to let Gloria and Ted into the apartment, they hired a locksmith. They searched through briefcases to gather papers, business records, for evaluation; they also took a copy of his will. The examining psychiatrists, meanwhile, were compiling their own findings, preparing for testimony if required. They had determined that Dahl was afflicted with arteriosclerosis — hardening of the arteries — and that there were resultant indications of atrophy of the brain, loss of brain cells, signs of “senile dementia.” According to the psychiatrists, Dahl showed erratic behavior while he was incarcerated; he appeared emotionally distressed; he exhibited “looseness of association”; his speech was slurred; he had memory lapses; he had mobility problems and occasionally stumbled. They were prepared to testify, if necessary, that George Dahl was a man of unsound mind.

Ted and Gloria hoped that there would be no testimony. It was possible, maybe even likely, that Dahl and his attorneys, upon reviewing the medical evidence, would choose not to contest the guardianship; that George Dahl would, at last, allow the trust to be put in care of the First National Bank and himself in care of Gloria Akin. Then the unhappy affair would be over and done with.

They hadn’t reckoned with the determined spirit of George Dahl. With his attorneys, he chose to fight, to put his sanity to the test of a jury. The private agony of a family would now go public.

On May 30, 1978, as the trial of George Leighton Dahl was called to order, Probate Courtroom No. 2 was full of tension, of a vague sense of gloom and the apprehension of impending ugliness.

Long before the trial, attorneys for both Gloria Akin and George Dahl had recognized that this would be an emotional tug-of-war; the facts of the case, such as they were, would be duly weighed, but the sympathies of the jury could decide the case. The jury might respond to the loving but exasperated daughter, saving her father from his own destruction. Or they might respond to the old man, fighting to save his dignity from the ingratitude of his once-beloved family.

Each side knew that a talented trial lawyer could be crucial to the winning of those sympathies. The Akin side brought in Bob Vial. Vial is a distinctive character, his sanguine complexion set off by a shock of longish, ultra-white hair; his presence is clever, easy, and charming. The Dahl side engaged the services of Louis Bickel. Bickel’s large build is vaguely athletic, his close-cropped graying hair is vaguely military, and his rimless glasses vaguely scholarly; his presence is domineering but attractive.

The two lawyers were well-matched. With Judge David Jackson — young, animated, intense, and a careful judicial scholar — the legal stage was set.

A long wooden table stretched across the front of the courtroom. As they faced the judge’s bench, Gloria Akin and her attorneys took their places at the left half of the table; George Dahl and his attorneys occupied the right half, closest to the jury box. Throughout the trial, George Dahl would sit under the close scrutiny of the jury. He sat stoically; his usually lively blue eyes, behind thick glasses, stared always straight ahead, betraying no emotion. Gloria many times would turn and look at him, as if hoping to engage his eyes; not once did he return her gaze.

The jury was a panel of six: all males, five white, one black, relatively young. From the beginning, they were highly attentive.

The charge to the jury read simply, “Do you find from a preponderance of the evidence that George Leighton Dahl is of unsound mind? Answer: He is or he is not.” With the charge was submitted a definition of unsound mind, taken directly from the Texas Probate Code: “Persons of unsound mind are persons non compos mentis, idiots, lunatics, insane persons, and other persons who are mentally incompetent to care for themselves or to manage their property and financial affairs.”

The Akin case would be directed at the notion of incompetence; they would seek to prove George Dahl incompetent to care for himself or his property. In such a case, the burden of proof technically rests with the appellant, the Akins; for the appellee, George Dahl, the tenet of “innocent until proven guilty” holds true. But in a guardianship trial, that burden tends to become twisted. Because George Dahl had already been placed under temporary guardianship by ruling of a judge (in this case the judge who was presiding over the trial), and because he had already been placed under mental evaluation by ruling of a judge, he needed to demonstrate that he was not incompetent. Much of the pre-trial discussion revolved around Bickel’s efforts to see that the earlier probate rulings would not reach the jury. But character witnesses would likely be needed in force to vouch for Dahl’s competency and the soundness of his mind.

When the trial began, there were only a few observers in the five rows of benches at the rear of the courtroom. Each successive day of the nine-day trial there were more. Always there were several lawyers in attendance with both sides, because of the large body of evidence, the number of witnesses, and the number of depositions to be read into evidence. It was more activity than Court No. 2 had seen in a long time.

The Akin case was presented first. The first significant testimony was that of Dr. Harvill. The testimony served basically to establish Mr. Dahl’s medical history, stressing a few incongruities, such as evidence that he often did not take all his pills as prescribed. But the most telling moment happened almost by accident. After enumerating Dahl’s physical disabilities, Vial elicited an opinion from the doctor: “Could you say, from a physical standpoint … he should have somebody looking after him or attending him on a daily basis?” Dr. Harvill answered: “I know of nothing that would make me have to say yes to that. I would say basically, no.” That response by Dahl’s personal physician had to be scored in Dahl’s favor.

Early in the trial, Adrienne Akin, Dahl’s 14-year-old granddaughter, was called to the witness stand to testify about an incident at the family table on Easter Sunday 1977. Adrienne had always wanted a horse and began asking her grandfather why she couldn’t have one. They began to argue and then, Adrienne testified, her grandfather got up, grabbed her arm, and twisted it painfully behind her back. In the struggle, Dahl fell to the floor. Adrienne ran upstairs, upset. For some time, Dahl refused to talk to her.

A substantial part of the Akin case was built upon the testimony of the three psychiatrists who had examined Dahl in the hospital ward. All three, in response to Vial’s pointed question, testified that, in their opinion, George Dahl was of unsound mind.

The cumulative effect of their testimony was potentially devastating. Lou Bickel, in cross examination, did not even broach the subject of the pure medical testimony, the brain atrophy indicated by the electroencephalogram. Instead, he attacked the testimony which applied to Dahl’s actual behavior suggested as the result of atrophy. He extracted admis-sions that, first, Dahl’s behavior at the time of the examinations in the hospital could be partly due to the stress of his involuntary incarceration. He also had the doctors confirm that much of their analysis of the behavior of Mr. Dahl was based on the history given them by the Akins prior to examination. He was also able to register, for the ear of the jury, another ringing statement: “During your examinations,” Bickel asked Dr. Thomas Woods, “did he [Dahl] do anything weird, strange, unusual, to lead you to the conclusion that he was of unsound mind? Did he do anything?” “No,” Dr. Woods replied.

As the trial neared its mid-point, Vial announced he was ready to tender from the deposition of George Dahl. The deposition had been taken a week before in Dahl’s office. Vial could have put Dahl on the witness stand but, at this point, chose not to. The reading of the deposition took hours. Its overall effect was difficult to measure. On one hand it illustrated Dahl’s feisty, even defiant spirit. He challenged Gloria: “I’m more competent than she will ever be.” He challenged Ted: “I think it [this lawsuit] is practically suicide for Ted and his political ambitions, but that’s his problem.” He even challenged his interrogator, Bob Vial: After a series of questions leading to his purchase of the engagement ring, Dahl said, “Why all this insinuation? Why not come out direct and ask me questions clearly?”

On the other hand, some of Dahl’s testimony, in its belligerence or its flippancy, could be construed by the jury as evidence of, at least, eccentricity. Vial and Dahl had this exchange:

Q: “What would you say would be the best hedge against inflation for a person to own?”

A: “To buy something.”

Q: “Well, would real estate be?”

A: “A bicycle.”

Q: “A bicycle?”

A: “Yeah, that’s one. Buy a bicycle.”

Q: “Bicycle?”

A: “Bicycles, plural. Say a thousand bicycles.”

Q: “That would be a good investment?”

A: “Well, I say it may be. Ten bicycles may be, a hundred thousand bicycles, anything you want. Neckties or whatever you want. We are reviewing all of these avenues now.”

At the minimum, though, the deposition indicated that the 84-year-old man was able to stand up under long hours of questioning. At the end of the deposition session, Vial said to Dahl, “You won’t get mad at me if I say I’m through?” Dahl replied, “I don’t believe it. You have got the reputation for being a tough guy. I don’t think you are.”

The reading of the Dahl deposition was followed by the reading of the deposition taken from Joan Renfro. For the most part it dealt with her divorce and the subsequent raising of her two children primarily by her ex-husband. It was an attempt to discredit Mrs. Renfro’s qualifications as a mother and implicitly her abilities to care for Mr. Dahl as his wife. The testimony was broached because the Akins were to claim that their aversion to Mrs. Renfro was based partly on her family history. However, her deposition proved mainly inconclusive in that regard. Vial chose not to put Mrs. Renfro on the stand, perhaps because her modest, motherly appearance was hardly the image of a golddigger. In fact, as a subpoenaed witness, Joan Renfro was not allowed in the courtroom until the end of the trial when all testimony had been taken.

The trial then focused on Dahl’s business judgment. There was exhaustive testimony regarding Dahl’s sale of the Gold Crest, his investment considerations, tax situation, and his management of the trust. There was testimony that Dahl was definitely not as sharp in his business judgments as he once was. There was counter-testimony that Dahl was every bit as keen a businessman as he had always been.

On the eighth day, Ted Akin was called to the witness stand. He was examined initially by Leigh Bartlett, Vial’s assistant. Early questioning had to do with the Lillie Dahl trust; almost immediately Lou Bickel began raising objections as to the admissibility and use of certain pieces of evidence. Both Vial and Bickel had, to this point, avoided heated debate. Now Bickel began objecting to the leading of the witness and the volunteering of information. It was clear that, in Bickel’s mind, Ted Akin’s testimony was occasionally over-responsive, with embellishment beyond the scope of the question. Finally Bickel exploded: “Excuse me, Judge. Is there any way we can stop this sales pitch in form of testimony? Is there any way, Your Honor? I’ve asked for instruction twice. I realize the gentleman is a judge, I’m at my peril to do it. I must ask that it be stopped.”

A new element now entered the trial: Attorney Lou Bickel versus Judge Ted Akin. It was an awkward situation. Bickel, an active civil attorney, often has reason to be trying cases in Ted Akin’s appellate court. They were well-acquainted. As a matter of form, it was uncomfortable for both Bickel and Akin to face off here; it was uncomfortable as well for Judge Jackson to serve as referee. To legal observers, it was also highly interesting.

On cross-examination, Bickel immediately questioned Akin about Akin’s financial losses, despite objections from Ms. Bartlett. When pressed by Bickel for confirmation of loss figures, Akin repeatedly answered that he did not know. Suddenly, Bickel asked, “Have you ever suffered from any mental infirmities … any mental diseases?” Vial jumped to the floor in objection, calling it “a degrading exercise in supposed cross-examination.” Bickel explained to the court that in prior testimony Akin had complained of the memory lapses of Dahl as indicative of mental infirmity; noting Akin’s lack of recall, he asked if there were associated mental infirmities. Vial called it “grossly improper” and asked the court to instruct Bickel to “keep it at least a foot above the gutter.” Jackson sustained the objection.

“I object to that, Your Honor,” Bickel retorted. “This gentleman and his wife have uttered the defamation of incompetency publicly against my client and to now dignify by saying my examination of him is on a gutter level, as Mr. Vial suggested, is an outrage.” Jackson quickly instructed the jury not to consider the exchange as evidence and again sustained the objection.

Bickel continued to pound at Akin. Vial made a motion “that common courtesy not be dead in the courtroom.” Judge Jackson dismissed the court for the day and when the jury had gone, reprimanded Bickel for being “abusive of the witness.” Testimony resumed the next morning without further incident.

On Friday, June 9, Gloria Akin took the stand, the 26th witness to offer testimony. Her testimony chronicled the story of a family’s love turned bitter. Her voice carried the dull edge of regret. The cross-examination by Bickel was relatively mild. She stepped down, and Bob Vial rested his case. The court recessed for lunch.

Lou Bickel had a decision to make. To what degree would he offer up a defense of the man? It was his feeling that the evidence presented by the appellant had been less than overwhelming. Certain key elements had been blunted by cross-examination. His best guess was that the jury had not been convinced that Dahl was senile. To parade a host of witnesses to the stand in defense of Dahl now (Bickel had some 20 witnesses at the ready) might serve only to work against him. He decided to gamble. He would call no further witnesses.

By the time the trial resumed for final arguments, the courtroom was filled to capacity. Judge Jackson read the charge of the court with instructions to the jury. Leigh Bartlett began her final argument to the jury. She recounted the body of evidence that pointed to Dahl’s incompetency. She stressed the medical testimony. She stressed that he is “not the same man at all, a different man than he was in 1965 … who doesn’t react the normal way, doesn’t react the way he would have in the past, and doesn’t react the way a man of sound mind would react.” She stressed the incident with Clara. And she stressed that Gloria had brought this case out of love and sought only to take care of him.

“My client is guilty all right; he’s guilty of being rich, he’s guilty of being 84, and he’s guilty of not dying,” Bickel said.

Bob Vial took over. His tone was casual, anecdotal, almost amused, as if there could be absolutely no doubt as to the verdict. He focused on Dahl’s financial judgment. “It’s my opinion,” he said, “that the Captain is no longer the Captain in this incident … I’m convinced that George Dahl’s ego is as big as Mount Everest … He’s been out of the architectural business for years. His family is set back for five years since he sold out to Dahl-Braden. Letting him have his office, I mean, gosh, let’s face it … If he wants to play in his own mind and say ’I’m still that great architect,’ and spend another $130,000 a year, let him. Let him for five years, but doggone, you know, enough is enough.” Vial then deferred to Bickel; Vial would still have the last argument.

Lou Bickel was intense. Besides refutation of certain evidence, he assailed the entire trial as preposterous. “This man has been dealt the ultimate insult. He has been dealt it, in the name of all things, love … This is just sort of self-made, homemade, across the coffee table and breakfast table and at a debutante party made-up kind of mental case … My client is 84 years of age. When he goes home tonight, I want him rid of the Akins. I want them out of his system. He has been Akined to death, except he hasn’t. He’s guilty all right; he’s guilty of being rich, he’s guilty of being 84 years of age, and, worse yet, he’s guilty of not dying; and for that combination of three sins, he will not be forgiven. They wouldn’t go to his wedding; I wonder if they’d go to his funeral? … They said that he rejects the ones that love him most. What are they talking about, loved him most? Expose him to a public trial and undress him, put every medical fact that ever existed, put supposition, speculation, public ridicule, and bring in a 14-year-old to tattle on her grandpa … He can run his business just fine. He can’t do too good a job of it in court, listening to a bunch of lawyers ranting and raving at one another, nor locked up in Presbyterian Hospital. But, give him his freedom, he can … The sole concern of these people is with respect to the property. They started talking money the minute they walked in this courtroom, and their charts all talk with money. Everything talks about it: money, money, money, money, money, money … Gentlemen, I’m going to be abrasive, I’m just going to be abrasive. I want him out of this courthouse by 5 o’clock tonight with a verdiet in his favor. I want him rid of these people. You are the only ones that can get him rid of these people … In due humility and all humility, I ask for my client’s verdict.”

Bob Vial had the last words. “It seems that Mr. Bickel’s oratory is more eloquent when he lacks a case than, having tried other cases with him, when he has evidence. I think he climbs to soaring heights, but I wonder what’s under him but air? … We are a country and a state and a county and a city founded on evidence, not flowery legal oratory. If Mr. Dahl is competent, as he would insist, then it is about 19 feet from where the man has been sitting to the witness stand to answer questions and to demonstrate to you gentlemen that he is not emotionally labile … And with regard to the Lady Renfro … gentlemen, I thought marriage was based on mutual love, mutual trust, and mutual understanding … A marriage that’s founded with that sort of property exchange is no marriage at all … If for all other reasons aside, but just for Mr. Dahl’s own best interest, his own best health interest, he needs someone to look after him and someone to be responsible for him … He has no business driving … Somebody is going to get hurt and seriously. Both Mr. Dahl and some innocent people … We feel that when you consider the evidence, and you consider the Court’s definition of unsound mind, that there is only one inescapable finding that you can make, and that is that Mr. Dahl is of unsound mind. Thank you for your attention.”

There is no jury room in the Probate Courts. The jury confers in the courtroom, while all others wait outside in the hallway. For the number of people milling there, the hallway was quiet. Bob Vial and Lou Bickel both looked tired. Everybody, in fact, looked tired. It had, indeed, been an ordeal. The only person who didn’t look tired was George Dahl. If he was concerned, he didn’t show it; he was chatting with a friend about investments. Everyone waited.

In only 25 minutes, the court was called back into order. The jury had reached a verdict. The thick, silent tension was relieved only by the drone of rush hour traffic outside the courtroom windows.

Judge Jackson addressed the jury. “You have reached your verdict. I’ll read out the question and the answer to the question and then ask you if that is the answer to the question. ’Do you find from a preponderance of the evidence that George Leighton Dahl is of unsound mind?’ Your answer being ’He is not.’ Is that your answer?”

The jury foreman replied, “That’s our answer, Judge.”

A joyous shout went up in the courtroom. There were many tears, many hugs. There were tears in the eyes of George Dahl, but he remained the calmest man in the courtroom. As he shook hands with members of the jury, he told them in his raspy voice, “I hope your family never does to you what mine has done to me.” Now, crying, Gloria approached her father as if to take his hand or hug him. He turned away. They haven’t spoken since.

Six months after the trial, George Dahl married Joan Renfro. Their wedding was a very small affair, in the Canterbury House chapel at SMU. The Akins did not attend; they would not have attended had they been invited. A few weeks later, the newlyweds hosted a gala open house reception in their apartment. Friends noted that George still played the cavalier husband, teasing about how long it had taken to find the girl of his dreams. Joan still played the demure bride; her sweetness with George was as sugary as a teenager’s.

A few weeks later, they went on their honeymoon trip to the Caribbean.

But when a family commits its private troubles into the hands of the law, the law does not easily let go. The guardianship case has been appealed; the appellate materials are currently awaiting the scrutiny of the Court of Civil Appeals in Amarillo. Four related suits have been filed. The Akins have filed a state court action suit on the three notes they are owed by Dahl. They have also filed a suit requesting the removal of Dahl as trustee. Dahl has filed a damage suit against the Akins in state district court alleging defamation of character, false arrest, wrongful imprisonment, abuse of process, and seeking return of property. That action was originally filed as a federal civil rights action suit, was initially rejected, and is now being appealed.

It is a legal snowball that no one is happy about. Says Gloria: “I wish it had never happened. I know the Lord must have a reason for this. I just hope other families can learn from what has happened to us.” Says Ted Akin: “George Dahl was a brilliant man. I hope he will be remembered for that, not this.” George Dahl prefers not to talk of it at all; he loves to talk of his career, and hates to talk of his family. Says Lou Bickel, “It’s an absolute shame that this old man can’t live out his days in peace. It’s a case of another modern legal tragedy — nobody wins but the lawyers.”

Author