Editor’s Note: This story was first published in a different era. It may contain words or themes that today we find objectionable. We nonetheless have preserved the story in our archive, without editing, to offer a clear look at this magazine’s contribution to the historical record.

The way he told it, Jack Proctor awoke one noon in his sleazy garage apartment in Cleburne, Texas, and dismally considered whether he was alive or dead. Except for the pulsating pain in his head, Proctor was numb and he concluded from dreary experience that feeling would soon creep back into his extremities, accompanied by excruciating jeebies. This was a traumatic stage whenever Jack Proctor sobered up, which was not at all often.

To compound his miseries, the clock on the nearby Johnson County courthouse started banging its noon message — torture beyond justification for a man in Proctor’s state. Ten bongs, eleven bongs, twelve bongs, thirteen — what? Fourteen, fifteen. The clangs came more rapidly until they were almost a single heinous note.

He could see the clock from his only window and when he got his aching eyes in focus, he saw the hands spinning on the huge clock face. He knew this was it. He had finally flipped. Oceans of rum and cheap gin and foul scotch and raw bourbon, over two decades, had done it. He was not yet dead; he was bound in alcoholic purgatory. There, with the hideous vibrations beating against his poor skull and the giant hands circling the dial, Proctor promised the Lord and whoever else was listening that, given a pass from this horrible joint, he would never put another demon drop down his neck.

It wasn’t until days later Jack discovered that workmen were repairing the courthouse clock that day and that the hands really were spinning and the bongs bonging. But he had made his pact and in his remaining 18 years, Proctor never broke it.

(Of course, he did get onto some suspicious coughdrops later on. They were Vicks, he said, but were made with such a strong narcotic ingredient that he had to buy them in a liquor store.)

You could put the lie to the cough-drops — although he did seem to use an uncommon lot — but the courthouse narrative might have been valid. But when you started separating the truths from the untruths, you destroyed the person.

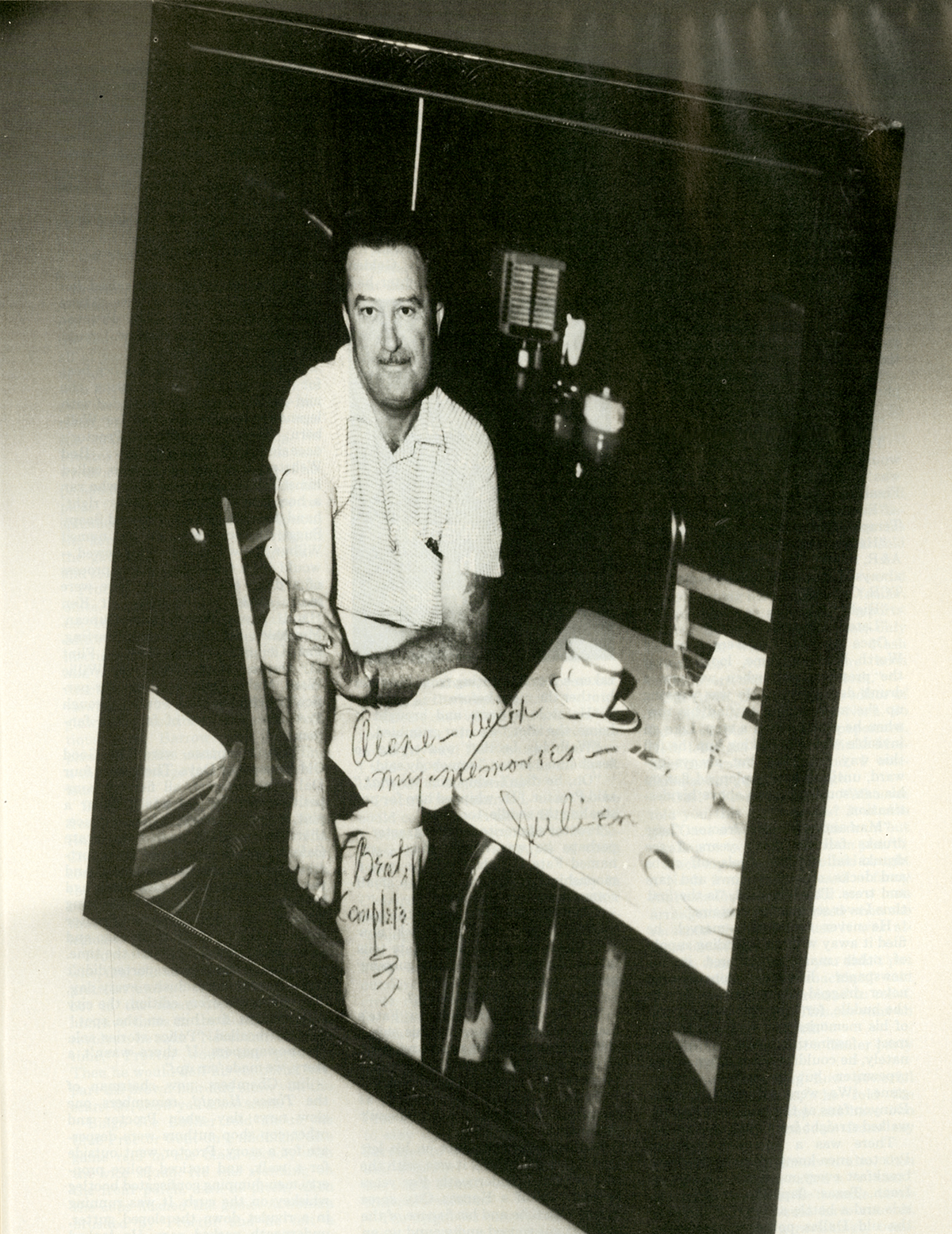

Proctor, for some reason, renamed himself Saintly Julien. It seemed to fit as well as anything else.

I once wrote in a 1965 Dallas Times Herald column:

“Mr. Jack Proctor, before he became editor of The Richardson Daily News, led a most adventurous life to hear him spell it. He sailed the seven seas, wrestled professionally under the name of Jim Lon-dos, captured John Dillinger single-handedly while posing as a broad in a red dress. He frequently dated Norma Shearer, taught Will Rogers how to chew gum and invented the sand wedge. This is not to say Mr. Jack Proctor takes liberty with the truth. It is hard indeed to take liberty with a stranger. Chances are Mr. Jack Proctor wouldn’t recognize the truth if it walked into his bedroom, sat on his chest and fed him oatmeal with a great horn spoon.”

Minutes after these words appeared on the street, Jack Proctor called to say his lawyer would be in touch shortly with notice of a libel suit, but in the meantime how about meeting at Shanghai Jimmy’s for some chili and rice.

It was in Cleburne, Texas, in 1947, that I joined the Proctor cult. He was in Cleburne out of necessity. The Times-Review was desperate for a sportswriter-newsman and Proctor was desperate for a job of any sort. He had been fired off a half-dozen sheets because of the bottle and he departed his last stop, Galveston, rather hurriedly because he also had hung paper — meaning he had written several checks that were not immediately, and never would be, negotiable.

Cleburne was a good hideout for him. It was in a dry county, but was only an hour’s bus ride from the nearest liquor store in Fort Worth. Every payday, Proctor would put on his overcoat, no matter the temperature, and catch the Greyhound for Cow-town where he would fill his many pockets with half-pints. This is the mark of a drunk, he later explained. Half-pints are handy to carry without making a telltale bulge; you are never without help.

First time I remember seeing Proctor was at a high school bi-district football game in Cleburne. There was this small, dapper guy in his early forties, with a pencil moustache and big brown bird dog eyeballs and roached brown hair, chain-smoking and gabbing. I tabbed him for a pro juicer because a real hooked boozer never wants to drink in front of witnesses if he can avoid it. He ain’t proud of it.

Almost everybody in pressboxes in those days carried a little stimulant, partly to negate the cold wind that came through the cracks, partly because they thought it made them more fluid and lucid at the typewriter, and partly because they had seen The Front Page too many times. Proctor had nothing showing. No tattletale bulge. He would disappear from the ramshackle pressbox occasionally, and when he returned his eyes would be brighter, he would smoke more feverishly and jabber louder and faster. I was on The Fort Worth Press at the time, and Proctor read our paper daily, he said, and was familiar with some of the crap I was trying. He also said, at great length while I was trying to watch the Bryans or the Corsicanas or the Temples or whoever the hell was bidistricting, that he had once managed Fritzie Zivic and had promoted fights on the Gulf Coast and had worked on all the old Dallas papers during The Good Old Newspaper Days and was on first-name basis with every broke and shill and asspocket bookie and whorelady on Galveston Island and why didn’t I come visit him at Cleburne sometime.

The next I heard from Jack Proctor, a dowdy little woman in a flowery bonnet walked in the Press office, said she had ridden a train from Cleburne and did I know where Jack Proctor could be found, as they had been married a couple nights ago and seems like he had since disappeared. No, it wasn’t a regular wedding, she said. She thought he called it a Scottish Rite ceremony and that, somehow, I had spirited Jack Proctor away from her side.

Well, Proctor always denied the story but it did not escape nor ease my discomfort at the moment, especially because I excused myself to go to the men’s room and stayed there two hours until the lady despaired of my returning and left.

Along about then, Proctor was going through the legend of the bonging courthouse clock and swore off. He joined Alcoholics Anonymous and became an energetic worker in same, although it never seemed to bother him to be among the rest of us degenerates when we were popping tops or choking down cheap bourbon.

Jack became a LaGrave Field pressbox regular, when Bobby Bragan’s Cats were at home, and he soon became the non-resident elder statesman and historian and constant lecturer to the Press sports staff, a rather unorthodox collection that included Dan Jenkins, Bud Shrake, Jerre Todd, Charley Modesette, Puss Ervin, Andy Anderson, Gary Cartwright and others who came and went with lesser ripples. Proctor recognized no one, however, by his proper handle. Sherrod became Blackwood Sheridan. Jenkins was Jenke, Shrake was Thor because he was 9 feet tall. Todd was Spanky, The Child Star; Modesette was, naturally enough, Modesty; and Anderson was Andrews. Then Proctor had a few Cleburne pals whom he inducted into the group, a Times-Review reporter named Pete Smith whom Proctor called Puck Smythe and a giant Yellow Page salesman he referred to as Bad Hair Bentley, obviously because of a flat mat of red Brillo on his head. Proctor, for some reason, renamed himself Saintly Julien. It seemed to fit as well as anything else.

There also were other Clebumites named Mad Adam and Ugly and Emit Mewhinney and a black man who worked at a gas station whom Proctor called Yere-Yee.

What?

“A n****r has a special tuning fork in his ear, like a dog, that can hear sounds nobody else can,” Proctor explained seriously. “Yere-yee is one of those sounds. Look, I’ll show you.”

This first happened when we were standing on Akard Street in downtown Dallas. Across on the other side, 40 yards away, a black man walked in the opposite direction.

Jack put his hand to his mouth. “Yere-yee!” he shouted. Sure enough, the black man wheeled in his tracks and looked back at us.

“See?” said Proctor, quite satisfied with himself. Of course, other pedestrians and a couple truck drivers also turned and looked at us, a fact Proctor blithely ignored.

Proctor loved blacks. Once we were in a buffet line at a press luncheon in the Fort Worth Club. An old black man was ladling the barbecued shrimp, a dish dearly loved by Proctor. While standing in line, Jack devised a way to get an extra large helping.

“Watch me bring him,” he whispered to me. “Watch me give him some numbers talk,” referring to the ghetto policy racket.

Proctor reached the shrimp cauldron and held out his plate.

“Fo, lebben and forty-fo,” Jack said.

The old man did not even raise up. “Straight up and down,” he said automatically. “Thas the Dixie Queen.”

Then he lifted his eyes for the first time and stared at Proctor, who was grinning.

“I’d say you have been among my people,” the old man said.

“Born in Memphis,” Jack said.

“Well I admit, on Beale Street,” said the old man, “one do occasionally see a colored face.” Then he heaped shrimp on Proctor’s plate until his thumbs were buried.

Proctor had his own language. State cops were highway petroleums; the guy with the drill was a tooth dentist. Women of the streets were whoreladies. Then there was his backwards gimmick. Tattoo was too-tatt. Jail was gowhoose. A big car, regardless of the make, was a Cadil-lac-Buick. And when he called on the telephone, there never would be a hello. He would start the conversation in the middle.

“Times Herald sports — Sherrod.”

“He ought to be walking in the door right now.”

“Who, for crissakes, who ought to be walking in the door?”

“The lawyer. He has the libel papers to serve you. I don’t stand still for no watermelon conversation like you strapped on me in today’s paper.”

“Bite me.”

“This is chili-and-rice day. Meet you at Shanghai Jimmy’s at 12:30.” Click.

You eventually got used to his telephone style. It was a challenge.

“Times Herald sports.”

“His last name was Doss.”

There would be a silence while I would fight the clue frantically. It was a disgrace to show confusion. Finally a cog would catch.

“First name, Noble,” I’d say. “From Temple, Texas.”

“He caught the pass that beat A&R, right?” (For some reason, it was always Texas A&R with Proctor. Or TCR. Or SMR.)

“Right.”

“Later.” Click.

Jack worked the Dallas police beat for the Dispatch during the mid-30’s. “If there wasn’t a story,” he said, “We made ’em up.

Once the two of us were at a Fort Worth baseball game, looking over the pressbox rail, when we saw a drunk defy gravity. He was weaving up the aisle, trying to find his row, when he stumbled on a step. Like an invisible wire was jerking him, he fell this way and that, but always upward, until he finally plopped flat on his can some ten rows above his destination.

“Man and boy,” said Proctor. “I see drunks fall for 40 years. I see drunks fall off bar stools, off curbs and docks, out of windows and cars and trees. This,” he said, “is the first time I ever see one fall upstairs.”

He never forgot this marvel; he filed it away with an unending supply of other marvels gathered in his newspaper lifetime. Conversation never dragged when Proctor was in the huddle, for he would pull out one of his memories and weave it in the most fascinating style. Unfortunately, he couldn’t put it down at the typewriter, but he talked a mean game. (We were all great Damon Runyon fans at the time, and Proctor walked straight from the pages.)

There was a one-eyed cowpoke Proctor once knew who ate the same breakfast every morning in a cafe at Iraan, Texas: flapjacks, chili on the side and a bottle of Pearl. There was the old Dallas police reporter who was beset with the idea of killing himself and tried it often when he was juiced up. One morning, the reporter showed up for work at the police pressroom with a Band-Aid on his forehead. He had tried to shoot himself and missed. The others laughed and laughed to see such sport.

“You’re right,” the guy said morosely. “I coulda done more damage with a rock.”

And then there was the Cleburne middleweight, Jack Something, whom Proctor managed. Had to scratch his tiger from a Fort Worth Golden Gloves bout because the fighter had taken a fearful beating from his older brother the night before.

“He stole a horse and brought it home, the idiot,” Proctor grumbled.

“Well, his brother was trying to teach him a lesson,” somebody said.

“Oh, he didn’t whip him for that,” said Proctor. “He whipped him for not stealing the saddle, too.”

Proctor’s favorite local character — perhaps he was fiction too — was named Fate Callahan, and he was a moonshiner from Goat Neck, a small community near Cleburne.

“They tell me Fate makes the best stuff in these parts,” said Jack, now very much the towteedler. “Fate tells me he started that famous guessing game.”

That famous guessing game?

“Three guys come out to Fate’s house and buy a quart of his shine, then go into the front room and drink it. One would go to the can and the other two try to guess which one left.”

Proctor’s yarns were tricky; as fanciful as they sounded, you dassn’t challenge.

He had a faded tootatt on his left arm. An eagle, I think it was, with the word “Trixie” underneath. For years he had told of a Kansas City spree during which he and his fiancee of the moment got soused and wound up on skid row, where they got tattooed with each other names. We all scoffed. One night, during a Cotton Bowl week in Dallas, Jack called me to his room in the old Jefferson Hotel. He introduced me to a strawhaired biddy of considerable vintage. He said, meet Trixie, an old girlfriend from Kansas City.

I stared hard at him. He looked back blandly, but squarely.

“Excuse me, ma’am,” I said, a little triumphantly, “this guy …”

Jack interrupted. “Show him,” he said.

The old gal obediently raised her skirt above one plump knee. There was a tattoo: J*A*C*K. Proctor turned to gaze at the window. I could see his shoulders shaking.

Jack worked the Dallas police beat for the Dispatch back during the mid-30s when the city abounded with legendary newshounds like Ira Wellborn; Eddie Barr, one of Proctor’s occasional brothers-in-law; Red Webster; a sports editor who called himself The Great Ben Hill, who ran a horsebook out of his lower right-hand desk drawer; a gal named Soapy Suggs; a telegraph editor named Wilbur Shaw who — Proctor vowed — would drink 10 pints of gin in process of a day’s editions. And there were many others — the dour wit Ken Hand, Lewis Bailey, Bill Duncan, Marihelen MacDuff, Frank Harting, Pat Kleinman, Clarke Newlon, Flint D. Dupre, Pierce McBride, Willie Ward, Mabel Duke — whom our particular clique knew only through Proctor’s outbursts of fact and fantasy.

These, I suppose, were The Good Old Newspaper Days. There were four Dallas newspapers, all fiercely competitive; bootleg gin was a dollar a pint, delivered; hookers were a deuce; there was a place named the State Cafe where owners would let reporters eat on the tab until payday. And the Texas Centennial celebration had brought all sorts of interesting imports into town. Some, Proctor hinted darkly, were from Chicago and wore black suits and hats all the time.

“Listen, if the police reporter didn’t come up with an exclusive every day, or a new angle every edition, the city editor might fire him on the spot,” Proctor recalled. “Police stories sold the newspapers. If there wasn’t a story, we made ’em up.”

Jim Chambers, now chairman of the Times Herald, remembers one slow news day when Proctor and other cop-shop authors were desperate for a story. Proctor went outside for a walk and noticed police property men dumping confiscated bootleg whiskey on the curb. It was running in a rivulet down the sloped gutter, underneath parked cars. He looked both ways, tossed a lighted match into the stream and raced to the telephone with FIERY HOLOCAUST SWEEPS COMMERCE STREET. The fire destroyed three cars.

“I knew more about Dallas than any living citizen,” Proctor bragged. “Why, when a fire was reported, the truck man would call me and ask directions. ’Twenty-two hundred York,’ the guy would say, and I’d say, ’turn off at Calmont, up four blocks, yellow house on the left with a bore dark tree in the yard, and watch out for the dog.’”

Proctor once had a girlfriend in San Antonio, so he convinced his city editor (it could have been at any of the four papers, since he worked on all at various times) that he had set up an exclusive, private interview with Clyde Barrow at a certain hour at a certain farmhouse near San Antonio. The editor drooled. Barrow was the country’s leading mad dog. So Proctor was sent to San Antonio and wrote a daring, graphic account of his personal chat with the criminal, his pleas for understanding, a story resplendent in detail and description, the kerosene lamp light flickering on the gaunt planes of the killer’s face and so on. Hot damn.

Proctor returned to his Dallas office, confident of backslaps and maybe even a bonus. Instead, the city editor was loud and furious when he instructed Proctor to get the hell out and never come back. It seems at the exact same time Proctor was interviewing Barrow in that farmhouse, so glowingly described in Jack’s fictitious yarn, Barrow was positively placed 250 miles north, busily putting a shotgun charge in a highway petroleum.

Bingo Joe Luther, an oldtime friend from the sheriff’s force, and Ken Hand and Red Webster and Jim Chambers would spill similar Proctor stories, and he would laugh along with the rest when the tales were relayed but would never admit to any belief that he was not history’s greatest legman.

Proctor would tell of his everloving wife, first of many, who was one of the prettiest and no worse than a show bet in the mean department. Shot him five times in the head with a .32 revolver, he said. “Never missed me a time,” Proctor would say proudly. Then he would doff his snapbrim hat, part his brown hair, and show you the scars. Or show you some scars.

Bingo Joe Luther told about the time Proctor went on a midnight dice game raid in the black sector, with the vice squad. He was standing on the front porch, dark as pitch, when the cops flushed the game. A woman brushed by Proctor, and he felt a slight sting across the stomach.

“What he really hated,” said Bingo Joe, “is he had on this brand-new suit some gambler had laid on him. This gal and her razor made him look like Emmett Kelley.”

Proctor said he chased the black whorelady, caught her when she crawled under a culvert, kicked her in the puss a couple times, and then went to City Emergency hospital for a patch job. Holding a towel to his stomach while the doc threaded the needle, he called his everloving.

“Honey, I’m at the …” he began.

“Listen, you bastard, do you know what time it is?”

“Well, I know, but I’ve been cut and I’m at the hospital…”

“I don’t care where you are or what you’ve done! It probably was some broad anyway! How many times have I told you don’t never wake me up at this hour of the morning!”

Proctor was married, near as he could count, seven times. But he said it actually only amounted to five because he married a couple of them twice.

He married a nice widow lady in Cleburne — refined, religious, rather well-to-do. Jack was the most entertaining person ever in her sheltered Life. Heck, Proctor went respectable. They built a $65,000 home on the outskirts of Cleburne, with a trickling creek running through the backyard; he filled huge closets with fancy sports shirts and jackets, bought a cockatoo named Norton and a Weimaraner pup which, of course, he called a wisenhammer.

The dog, Impervious, was a prodigy. Proctor complained that he often had to stay up late, reading Homer and Socrates to his pet. “If I try to read him The Fort Worth Press, he bites me,” said Saintly Julien. “Especially the sports section.”

The neighbors complained. “Impervious goes down to the creek and catches all the perch, brings them back, cleans and puts them in the freezer. The neighbor kids don’t like it.”

To contain Impervious, Proctor had a 6-foot chain fence built around the backyard.

“First day, he cleared it in a single jump,” Jack reported. “Went to the creek and brought back a batch of shrimp.”

Shrimp?

“Fresh water shrimp,” he said. “Delicacy of Johnson County.”

Proctor said he raised the fence to 7 feet.

“He jumped it the first try. I got to go to eight.”

The next day. “Well, he jumped that one, too. The Mexican yard guys say they can’t go any higher. Something about Civil Aeronautic regulations. But I’ll think of something.”

Month later. “What did you ever do about Impervious?”

“I cut off one of his legs.”

“That do it?”

“Naw. Damn thing grew back.”

This particular Mrs. Proctor owned an auto supply house and a Nash distributorship. Moonlighting from his Cleburne newspaper job, Jack sold cars. Sold a bunch.

“Safest car ever built,” he would say, slamming his hand on the fender. “I can show you government reports. During the last calendar year, only two people were killed in a Nash automobile. And they were both bankrobbers, shot at a roadblock.”

Bill Rives, then the sports editor of the Dallas News, bought a Nash. So did a couple other newspapermen. Hell, I bought two, one a little Metropolitan made in England. I wondered about gasoline mileage.

“Gas!” Proctor roared. “Whoever told you this car uses gas? It makes gas. Once a week, you gotta drain out a gallon or two or it’ll flood on you.”

Once my wife, who also had bought a Nash from Proctor, used a fancy Ambassador demonstrator on a loan arrangement and apologized when she returned the car because it was almost out of gas.

“Oh, thank goodness you didn’t put any gasoline in this machine,” said Proctor, wiping his forehead in relief. “I forgot to tell you. This car runs on frankincense and myrrh.”

Once he was late for a dinner party at our house.

“I keep forgetting how powerful this Ambassador is,” he told the guests. “I had to stop and have two Cadillac-Buicks removed from my tailpipe.”

That marriage dissolved also, then Jack wed what he called a “runner.” Occasionally when he’d come home from work, she would have run off. Next was Betty, a ravishingly beautiful brunette whom Jack met through his work with the AAs.

About that time Proctor disappeared from the Southwest press-boxes for a couple months. We would call, and he was vague with his reasons. We thought probably he was recovering from a busted nose or something similar because people were always putting the slug on Proctor. Once, a wealthy rancher named Sexton died, and there was a big hullabaloo over his will, and Proctor covered the court proceedings like he was Heywood Broun at the Scopes trial. The Times-Review readership wasn’t accustomed to this Front Page Farrell type of reporting, so Sexton’s ranch foreman occasionally looked up Jack and gave him a black eye.

He complained that he often had to stay up late reading Homer and Socrates to his dog, Impervious.

Once Proctor covered a high school game in which the referee, as he was giving the signal about which team won the toss, was seized with a cramp in his leg and fell to the ground writhing in pain. The umpire bent over to administer at the instant the referee desperately kicked his foot in an effort to rid himself of this spasm. He kicked the umpire squarely in the mouth, knocking out a couple teeth. The umpire reeled blindly and fell over the Cisco team captain, who had knelt to tie his shoe. The team captain suffered a broken collarbone.

Proctor, in his game prose, referred to the officials as the Marx Brothers. The referee happened upon the editor on a Cleburne street the next week and whopped him on the eye. Proctor had always told his audience that he had both boxed and rassled professionally, but apparently the referee didn’t know that, for he bopped Proctor several times on the eye. Suddenly, as fate ironically decreed, the referee was stricken with the same muscle spasm that had beset him in the game, and he fell to the sidewalk. Proctor then tried to kick the fallen man, but his vision was so blurred by his swollen eyes that he missed, and booted a nearby fireplug instead, breaking a toe.

Anyways, the reason Proctor was missing from the scene, we soon discovered, was that he had all his teeth pulled. When he did show, it was with a sparkling set of storeboughts.

“Fit?” he said. “You ask if they fit? Listen, this job is the marvel of the dental world. They’re writing clinic papers on it. These teeth fit so well, they’re actually growing into my gums. See this one?” he tapped an incisor, “I had to have the damn thing filled last week!”

For a half-dozen years, Proctor and his Cleburne cohorts sponsored what they called a Mid-Winter Olympics for the Press sports staff. It was an overnight affair, climaxing with a 100-yard dash at dawn which nobody, to my recollection, ever finished. Proctor made his plans in great secrecy, bidding us meet on a Cleburne hotel parking lot at midnight, then guiding the procession through the night to somebody’s borrowed lakehouse or ranch house or, on one occasion, an abandoned motel.

Proctor, as Saintly Julien, always dressed in some outlandish costume, insisted that everybody prepare some sort of act to liven the proceedings. As the affair was stag, some of the acts would get a little raunchy. But some were quite artistic. Jenkins and Todd once wrote a complete musical, sang and danced with straw hats and canes. Shrake, Sherrod, and Cartwright once rehearsed a trapeze act called The Flying Huzars in which they appeared in long underwear and capes. Proctor wrote a play, a three-act drama entitled Is This Then All?, cast with his Cleburne chums, including Yere-Yee, and it was so bad it made your eyes water. Proctor turned his cap around backward, wore puttees, sat in a canvas chair, and directed the thing through a megaphone. And then there was the indelible memory of Andy Anderson, old aviator’s leather helmet on, goggles and all, lights out and only a flashlight shining up into his somber face as he sang a cappella, Lucky Lindbergh, Hero Of The U.S.A. Great Gawd Almighty, where have all the blossoms gone?

One day, word trickled. Summertime, 1962. Proctor had a sore spot on his gum that wouldn’t heal. Biopsy. The Big C. Some of us visited him at Harris Hospital in Fort Worth the night before the operation. He was sitting up in bed, telling of the Dispatch story he once wrote about a guy — now quite prominent in Las Vegas — who hit another on the head with a piece of his car. “Benny Bin-ion, the Bumper Beater, I called him,” said Jack. “Binion bought extra copies. Thought it was the greatest thing he ever read.”

The operation lasted 10 hours, and they took away part of his jaw and face. Hours later, in the intensive care unit, he was sprawled with tubes and pipes sticking out of his gray skin, and gauze and tape covered his head and face except for one eye, peeping from the whole mess, flicking here and there wildly, like a trapped fawn. The eye swept across me, unrecognizing I thought, until he made a feeble scratching motion with his right hand. A bedside nurse hurriedly put a pad under his hand and a pencil between his chalky fingers. She cranked his bed slightly, and he slowly, laboriously scratched on the pad until finished. He fell back in his bandages, his one eye flickering past me to other restless points. I picked up the pad. In quivering, pitiful hieroglyphics were three words: Need poon tang.

Some of the newspaper wretches around the state pitched in their mites to help pay some of Jack’s hospital expenses. His Cleburne job, almost unbelievably, was not waiting for him when he got out of the hospital. Some other calls were made, and Loring McMullen put Jack to work on the Fort Worth Star-Telegram copy rim. Then he moved to a better post — editor of the Richardson Daily News. His visits and calls over the next couple years came a little less frequently, and his newspaper pals, those of us who were not too busy going our own ways, thought it was because of his scarred face. Maybe he was awaiting some scheduled plastic surgery before he would again join the crowd. Because it was his crowd.

Who knows? Maybe The Big C wasn’t whipped. One December day in 1965, the Times Herald police reporter called me.

“You ever know a guy named Jack Proctor?”

“Yeah.”

“Shot himself this morning.”

That afternoon, Shrake and Cartwright and some of us were at Nick’s A.C. on the waterfront. By then, we knew the police blotter. He had gone to a hock shop on Deep Elm the night before, written a $21 check for a little .22 handgun (painstakingly filling in his checkbook stub correctly!), sat on his apartment couch the next morning, and when wife Betty went to the kitchen for more coffee, she said, he outs with the thing and pop. He was 58.

We drank a couple beers in silence, each reviewing his own mental file on Saintly Julien.

Finally Shrake coughed.

“Son of a bitch could have called somebody.”

There were nods around the table and, as I remember, that was all that was ever said.

Author