As promised, here is the second installment responding to Mayor Rawlings’ points in favor of building the Trinity River Toll Road. Yesterday, I looked at “why only small cities are removing freeways from their urban core,” which of course isn’t true. For one, San Francisco has a much bigger job base in their downtown. Furthermore, as somebody from the Bay Area responded via twitter, their Metropolitan Statistical Areas are divided into San Jose and Bay Area. Their CSA or Combined Statistical Area is actually bigger than DFW’s CSA within a smaller land area. Small city indeed.

Today, is the point that congestion is killing the city and strangling the life out of the economy. Almost as if like a noose, say like a freeway loop around downtown.

There are three parts to the congestion equation: 1) what is congestion, 2) how do we accurately assess congestion, and 3) what are the most cost effective strategies for dealing with it in an equitable way that doesn’t inhibit economic growth.

The first part, what is congestion also has three components worth explaining, which will help answer the second two questions. First, congestion is obviously lots of people in one place. Of course, we don’t complain about it if we’re at a market or Klyde Warren Park or rush hour on the London tube or one of the world’s great shopping streets. In this way, congestion is like cholesterol. Cars are LDL, the bad kind clogging our arteries. People are HDL, the good kind, curing things, populating streets, patronizing businesses. (edit for mixing up cholesterols. Obv good kind is HDL, which you want more of; LDL less of)

Congestion only becomes problematic when it is entirely (or mostly) in cars. Cars take up lots of space. High traffic areas are noisy and polluted. Champs Elysees didn’t revitalize and become some of the most valuable real estate in the world until the frontage roads were closed offering increased pedestrian space, more cafe space, ie more space to linger, and greater buffering from the 80,000 cars per day moving past on the actual street.

Vehicular congestion has its root causes which are worth explaining as well. How, why, and where does it occur? The other part of the congestion problem being in cars is the distance between destinations. The distance between destinations is partially to explain for car-dependence. Inherent to this is land use imbalance. Either jobs are too far away from housing opportunities (or vice versa) or our daily needs aren’t integral to our neighborhoods, ie the corner store, a restaurant cluster, the barber shop, the butcher/baker/candlestick maker, etc. I’ll get more specific regarding the Trinity at the end.

The third factor in creating congestion besides cars and distance is the funneling effect of the modern road hierarchy, ie the variety of scales of roads instead of a more regular street grid. The core of this problem is the layers of jurisdictions overseeing certain scales of roads. You have the US Interstate system, state roads, the regional transportation council only worried about regional highway connections and controlling the majority of the money, then you have arterials, collectors, local streets and alleys, mostly under the jurisdiction of the city.

Within this hierarchy is the Thoroughfare Plan. Every municipality is required by the federal government to have a thoroughfare plan which categorizes every street into every possible level of the hierarchy. Bigger streets get priority of funding thus there is an incentive for munis to chase the dollars and over-size all of their streets. An odd quirk of urbanity occurs by doing so. The bigger a street gets the more disconnected it gets from its contextual grid. In other words, while we expand corridor capacity we’re actually reducing network capacity. Oops.

Now we know what congestion is. How is it measured and what do those measurements say? Are we indeed dying a slow death of congestion?

The official standard bearer of congestion measurements comes from our home state, the not quite annual, but more like occasional Mobility Report from the Texas Transportation Institute. Their analysis has loads of problems, but that’s for another time. Point being, officials all over the country pay attention to it, cite it, and make decisions according to it. So if other people will use it, then I will too (because it just so happens I’ve downloaded their entire database, which despite being an “annual” report hasn’t been updated since 2011 data).

TTI measures the costs of delays due to traffic congestion (never couched in delays due to road construction of course) as a dollar value per driving commuter. One problem with that is that their metric is based on speed rather than efficiency. The other is that places with less drivers tend to be punished by this metric. It looks bad according to the formula if there are less drivers. More delays divided by less drivers equals higher dollar count. Thus, MOAR HIWAY CAPASIDY NEDED PLZ.

Another problem with their metrics is that the highest congested cities just so happen to be the most economically vibrant, which perhaps is an accurate measure. Places with lots of economic activity, what cities do, attracting people together to facilitate social and economic exchange is friction that causes road delays. It’s hard to make a transaction when you’re barreling down the highway. That economic activity needs to be done away with in the name of smooth driving. Or so says the doctrine.

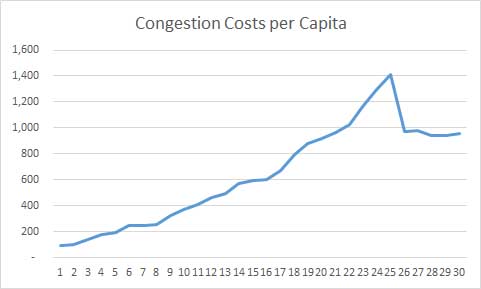

So what does their data say about Dallas? Well, according to their data, congestion costs DFW area commuters $957 per year. For comparison’s sake if its worth anything, it supposedly costs Houston $1297, Austin $930, and Detroit something like $880, which LULZ. They only calculate US cities, but I’ve seen studies estimating Vancouver’s at $300-400. This could be a difference of methodologies, but what is important is that YVR’s falls every year. You know who else’s congestion level is dropping every year? Ours.

DFW’s congestion according to TTI peaked in 2006 at $1400 per driver and has fallen ever since. Why? Well our vehicle miles traveled per capita has been falling every year. People are driving less. If people are driving less and congestion is as low as it’s been since about 1999 are we really strangling on congestion? Do we really need to expand highway capacity?

That brings me to the third and final point about where congestion comes from, highways themselves and the street hierarchy that disconnects the street grid. The beauty of the grid is that there are many parallel streets running in whatever direction you need to go. By doing so, it dilutes bad cholesterol, vehicular congestion, by offering a variety of routes. The system is adaptable. The many parallel routes also provide greater capacity. Downtown Vancouver’s grid has twice the street capacity as does the proposed highways they never built (had they actually been built).

Furthermore, and perhaps more importantly, the grid facilitates the agglomeration of synergistic land uses. While it dilutes the LDL, it attracts the HDL. Hierarchies of place naturally occur by how the market aligns itself. High value businesses go to high in-demand places and will pay the greatest premium to be there. Then other businesses will want to be near them and so it goes. Eventually that might either stabilize or become too crowded or no longer hip and a new area will emerge. The inherent densification impulse provided by the grid reduces trip length, which brings us back full circle. Land uses arrange around each other in a more efficient pattern than how we currently build our high speed, get-from waco-to-frisco road network.

The way we’ve planned and built infrastructure for the last fifty years in this city undermines that. Every other city in the world has learned this by now. We haven’t and thus we need a highway parallel to another highway because of antiquated if not nonsensical terms like Lane Balance which means the more destinations in the core the more highway capacity is required. Rinse and repeat until there is no city left. No destinations, no congestion. Traffic engineering wins.

That brings us to the proposed Trinity Toll Road and the third part of this post, what to do about congestion?

Well, the one way, the quick and easy way politically is to simply throw more money at it, which means a parallel highway. Well, the easy part went out the window with the over-building of highways, meaning the public sector has gone broke. To continue the status quo, we’ve come up with the idea of toll roads, which is actually a decent congestion deterrent if it means tolling existing highway capacity because highways are effectively a free good. However, this is not the case. Instead, toll roads are the magic bullet providing financing the public sector can no longer.

Except. Except toll roads are a pigovian tax deterring driving, thus why they’re such a good anti-congestion measure, but an utterly terrible financial mechanism (that is except for the private entities billing fees).

So instead, of the quick and easy political solution which has proven not quick nor easy, we ought to instead turn to the longer, harder, but proven road of addressing the deeper issues of land use imbalance and trip length that I discussed above. Let’s look at those problems in the context of the Design District.

You probably know the Design District. You may live in the Design District in one of the new mixed-use buildings. You may have had a tasty beverage at the Meddlesome Moth. Several new residential infill and mixed-use projects have gone up in the last few years:

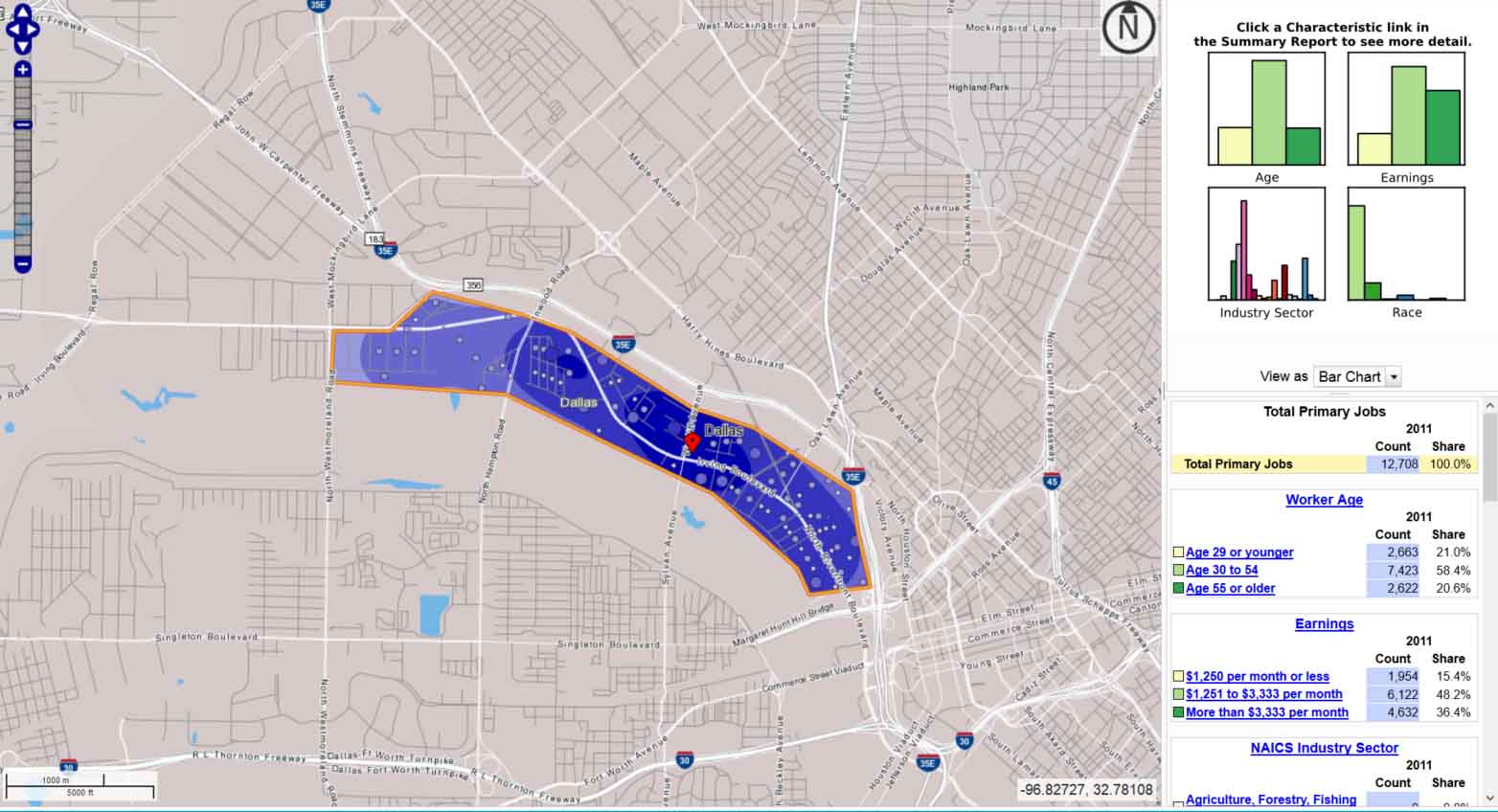

It was a great move on the developers’ part seeing that uptown was running out of land, there was opportunity just across Stemmons where new amenities in the Trinity Strand Trail and the potential of the Trinity River Park, as well as the job center that is Stemmons Corridor. Remember the earlier point about housing near jobs? Well, if we look more closely at this area in question we see despite the overall Stemmons Corridor having over 100,000 jobs, this segment of it along the Strand and Trinity River only has about 12,000 jobs and largely low intensity land uses.

There is huge residential demand for this area that will only continue. Unless a second highway envelopes it. The congestion along Stemmons comes from what I pointed out earlier, land use imbalance, trip length, and the funnel effect pushing all trips up onto the highway due to disconnected local grid. Of the 117,000 jobs in the area, there are only 13,000 residents (in all of Stemmons Corridor Business District). That means more than 100,000 must commute in. Despite having several train lines running through here, it’s mostly in cars. Furthermore, about half of those jobs pay less than $40k per year, so a toll road will only further punish these commuters.

Instead, the answer is development. More city. Not more highway capacity. The market will solve the problem of congestion if we help it deliver more housing where it wants to be, near jobs and amenities. The highway kills that demand.

To take a quick look at the opportunity cost if the toll road were to be built, I looked at five of the new development projects in the area compared to five low intensity land uses in the area, compared their assessed and taxable value. This was only an hour’s worth of study so I expect to get into it in more depth, but I took the average of those mixed-use projects and then projected what if we could encourage half of the available land in the study area shown above to be developed furthering the area as a funky, mixed-use, walkable neighborhood.

I estimated the area has about 910 acres. If we can redevelop half of that acreage, that is 455 acres in play. The average of the five new mixed use projects is 320 residential units on 4.4 acres assessed at $284 per square foot of land area. The low intensity land uses average out to $20.89 per square foot, 1/14th the taxable value per land area. You’d think we’d be doing everything possible to encourage density, walkable neighborhoods, and shorter trips.

Since I like round numbers for these quick exercises, those 4.4 acre projects factors into 455 net developable acres at a perfect 100 new mixed-use development projects throughout the area (don’t check my math). Those 100 projects, say over 20 year development time span, would add 32,000 residential units to the area, much closer to all of the jobs in the medical district. In other words, if there are 1.5 people per residential unit and a fair share are workforce housing given the incomes of the jobs in the area, that’s 47,000 people living closer to jobs, transit, and amenities. Those people and new density bring demand for services and more jobs themselves.

On top of that, the new density brings tax base, which we should be encouraging rather than more tax burden by way of highways and toll roads that the public sector will ultimately end up on the hook for in the way of a future bail out. Scaling the five low intensity sites over the entire area equates to about $818M in tax base in the area. However, if we cut that in half to $414M and redevelop the other half in the high intensity mixed-use, walkable format, that adds a whopping $5.628 billion with a B in taxable value. Add in the $414M of existing tax base and we’re over $6B in area tax base which would generate $155M in property taxes each year.

There’s your cost of the toll road in ten years of property taxes, all by not building it.

Is that doable? Why not? Over a twenty year build-out that’s only 2% of regional growth, of which the city currently captures less than 1%.

Maybe we could put that to things we need like investing in people (education and training programs) and people-centric places (our neighborhoods).