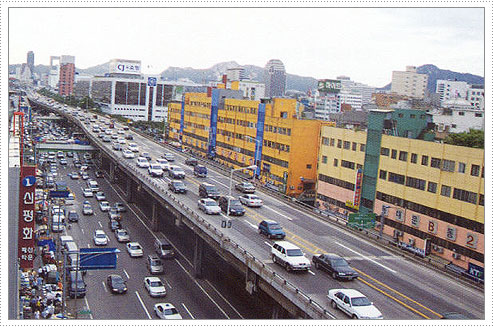

It was gross, or at least, I’m sure it was as any river used for human effluent might be. When the way towards a happily ever after future was found (cars/highways), the Koreans naturally covered up the stream forever to be entombed in what else, an elevated freeway through the heart of Seoul. In the 70’s, the new highway was hailed as a monument to progress, Seoul was keeping up with the West, all of whom were leaving behind poor backwoods Vancouver, which wasn’t building any freeways. Losers. Let’s all laugh at what a backwoods town Vancouver will be in the 21st century. snicker snicker.

Image from Preservenet.

Shockingly, this had its own consequences, i.e. ripping apart the vulnerable, formal and informal connective tissues that make up cities and all of the implicit advantages this connectivity brings. I’ve often used the brain as a metaphor for cities and vice versa. Reading the miraculous recovery of Gabrielle Giffords, I came across this:

“But it also damages neurons that don’t lie directly in its path, because it is trailed by a pressure wave that transfers the energy of the bullet into the surrounding brain tissue.

In brains, like in freely accessible cities, everywhere is connected to everywhere, however some parts are farther and more difficult to connect than others. Within organic, self-organizing cities, there usually is a reason for this. A bullet (or highway) slicing through it severs the complexity of the millions of potential connections for the prioritization of only point A to only point B.

Noise and congestion created by car traffic had deteriorated quality of life, polluted the air. Congestion is not necessarily a bad thing. Just when it means car congestion, which usually has no recourse to get out of it. Pedestrians are more nimble and can simply leave a crowded pedestrian zone. Cars, you’re stuck on that freeway, idling your time, car and spewing dollars, carbon monoxide into the thin air.

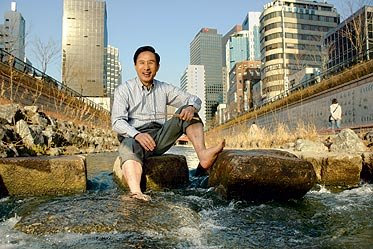

Along came Myung-Bak, a wonderkid, a CEO (of Hyundai) by the age of 35 decided to run for Mayor of Seoul on a platform of removing the freeway and restoring the city to its people. The larger metaphor here, is that we no longer need the reactionary impulses towards industrialization’s dirtying of cities. Cities can be clean and safe these days, so why run from the problems (and the inherent, associated advantages of cities) you abandoned?

Myung-Bak was swept into office aloft this populist wave. However, as with all new ideas and/or counters to the status quo and conventional wisdom, the idea of removing a freeway “vital to business” or whatever was treated with skepticism. Probably a similar skepticism that doubted Copenhagen going car-free for much of its central city. Lesson 1: this is natural. Business is ALWAYS acutely adapted to status quo (as it should be – if not, it would likely fail). It generally is allergic to change unless the benefits of that change are immediately understood.

The new mayor’s plan faced all of the same arguments, “omg traffic! businesses will die…and omg traffic!!” Any new idea requires incredible leadership and initiative armed with foresight.

To ensure success, Seoul set performance goals albeit entirely unrealistic ones – 50% reduction in private vehicle usage. It doesn’t really matter if they hit that goal, but it gives them the stars in hopes they hit the moon. Adding road capacity has never worked in addressing traffic congestion, so they sought to reduce demand.

I have seen project costs ranging from $200 million to $600 million, presumably dependent upon what is actually counted. While that seems like quite a bit for something that adds through subtraction, the economic impact has been substantial, around $2 billion in private investment since construction completed in 2005. That’s good public investment, leveraging public capital for increased private capital AND improving quality of life while doing so. It is easy to see how it this happens when you factor in all of the property that is 1) tied up as freeway ROW, and 2) all of the auxiliary and adjacent properties that are negatively affected by freeways.

The spin-off effects didn’t stop there, as the New York Times wrote in 2007:

“The man chosen as South Korea’s next president in Wednesday’s election owes much of his victory to a wildly successful project he completed as this city’s mayor: the restoration in 2005 of a paved-over, four-mile stream in downtown Seoul, over which an ugly highway had been built during the growth-at-all-cost 1970s. The new stream became a Central Park-like gathering place here, tapped into a growing national emphasis on quality of life and immediately made the mayor, Lee Myung-bak, a top presidential contender.”

Fundamentally, what tearing out the freeway did, was restore all of the neurons that exist within a complex, functional urban center. In contrast, the efforts to revitalize downtown Dallas, more resemble trying to win the Olympic biathlon while missing every single target and having to ski 20 repetitive penalty laps. It’s amazing how magic bullets never seem to hit the target. I’ll advise the USOC.

Freeways reduce intersection density, which operates as a substitute for network density. As Bill Hillier is showing with his studies of London, that there is a direct relationship between property values and connectivity in systems (even if it isn’t immediately bared out, eventually it will be). To counteract the negative impact of freeways because we falsely assume we would lose connectivity without them, we too often settle for weak compromises like “emerald necklaces” which is little more than greening up areas no one goes to nor wants to be in. We’re expending costs to overcome costs, trying to make four left turns just to go straight because there is a road block rather than removing the road block.

Image from Korea Times: Some columns were retained as monuments.

Another issue to be addressed is the notion of freeways as city walls. In some ways, that is correct as they are barriers to connectivity, but the effects of the analogy are misplaced. City walls forced dense development, a coerced sociopetality. You had to stay within them to ensure safety. Highways are sociofugal. They fling people away directly (because you can drive fast and travel far distances) and indirectly (as in, who would ever want to live on one?).

Removing the freeway takes a repellent force and creates an attractor, a center of gravity, a necessity for downtowns. Today, 90,000 pedestrians go to the new park in the center of Seoul, each day. 50 million have visited the new riverfront park in five years. It has become the center of Seoul, and by extension all of South Korea. Any city in the history of the world is polycentric, in that there are many centers of commerce and activity, that organize hierarchically based on access and popularity. Like any system, they both compete and cooperate.

However, the downtowns in the Sun Belt have been competitively knocked down several pegs, in a flatter, less hierarchical competition with suburban highway office parks. The result is reduced competitive advantage of urbanism, of interconnectivity that, as physicist Geoffrey West has shown is an increase in economic development by 115% for every doubling of population size. Sun Belt cities do poorly by these metrics precisely because of their disconnection. They have all of the problems associated with big city population but none of the advantages.

For a city to function, like a brain, intelligently, it has to be intensely interconnected so that the “cells” can communicate more intelligently, efficiently, and adaptively producing a more resilient system. The cells are the buildings and freely moving in and out of them is functionally reduced every time you have to get on a freeway and drive several exits. While highways are important connections on a macro level from city to city, within cities they are a barrier to this higher level of interconnectivity.

The modern city is no longer defined by high speeds and freeways. That TomorrowLand fantasy turns out to be Never Never Land. As is the course of human events, we eventually learn from our mistakes, usually after all other avenues are exhausted. High speed auto traffic is fine between cities but not within them. However, the attempt to increase speeds rarely ends up actually doing so. As the Jevon’s paradox suggests when applied to cars/driving/mobility, making driving easier increases the amount of drivers thereby making it more difficult. The future cities, the cities competing for global talent are focusing on livability. Tearing out inner-city freeways is the profitable solution, as Seoul has proven. The only thing freeways make more livable is someplace else.

Now, more pictures of the Chonggyecheon:

.jpg)