There’s only so much we can pass down, try as we might. I’m a sports maniac who is the father of a teenage sports maniac, most of whose close friends are fellow teenage sports maniacs. So I suggest the following with more than just a little authority: mine might be the last generation with a sweeping love of baseball.

According to a 2020 Morning Consult survey, while Major League Baseball trails only the NFL in terms of adults who consider themselves at least casual fans of the sport, the story is very different among Gen Z (those born between 1997 and 2012). MLB is a distant sixth for that group, lagging behind pro and college football and basketball as well as esports. And if you don’t believe the data, just ask them.

“My friends who don’t play the game don’t care about it,” says my son, Max, a junior infielder at J.J. Pearce High School in Richardson. His experience with the game grew from bystander to diehard well before he could read the backs of his baseball cards. As for most of his peers? “They don’t understand why I like baseball. They think it’s boring and slow.”

“I have only a small handful of friends that I can talk baseball with,” agrees his teammate, junior outfielder Dean Balo, who is in the running for the biggest Dodgers fan in North Texas. “Because most of them barely know anything about the sport.”

“Baseball’s popularity is dying with my generation,” adds Garrett Schroeder, close friends and teammates with Dean and Max for more than half their lives. “And I feel as if it’s [because of] the game’s inability to evolve.”

This, of course, has been baseball’s challenge for decades, and it continues to mount with the explosion in both technology and the sheer breadth of entertainment options. Other sports provide a density of in-game action and the apparent lure of sensory overload that baseball can’t. They favor inhuman feats of elevation, speed, and strength—and lionize them. Baseball is never going to put in a second fence to add an extra run for the most majestic homers or give a manager a strategic chance to go for two. The game, in large part, is what is.

And that was true well before TV blackouts and a lockout plodding toward 100 days yanked the game further away from a generation with more choices than any before it. Football, for all its scandals and legal issues that permeate the game and seldom let up, hasn’t had a work stoppage that led to canceled games in 35 years. And kids who grew up here haven’t had a Cowboys game blacked out in their lifetime.

I was 12 during the 1981 players’ strike, and my memory of it centers on the weird split season. The Rangers, having never been in a playoff game, finished 57-48 but missed the postseason, while the 50-53 Royals made it.

Things were more vivid the second time around. I was 16 during the 1985 strike. It ended up taking only two days in August for the players and owners to figure things out, but I was worried all the same. I was about to start my junior year in high school, and the game had cornered a much bigger chunk of my life than ever before. The Mavericks, though they’d begun to have some success, were still only a fifth-year franchise. The (North) Stars were still in Minnesota. The Dallas Blackhawks minor league hockey team and the NASL’s Dallas Tornado had ceased to exist several years earlier. I needed Major League Baseball to not stop playing.

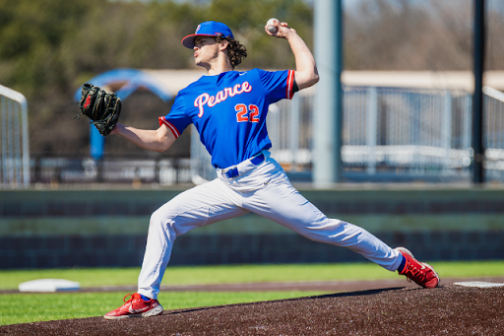

Stefan Stahl, a pitcher-outfielder who heads Pearce’s rotation this season and hits in the middle of the order, depends on the game in his own way. Despite countless alternatives at his disposal, baseball is still part of the senior’s routine even away from the field. There’s a big-league ballgame on his TV or phone whenever he’s knocking out his homework, keeping him company all the way through the late West Coast starts.

But if the current owners’ lockout ends up delaying the 2022 season by more than the one week it’s already claimed?

“I would probably have a Netflix show running in the background instead,” he admits. “It would definitely be less enjoyable, but it would be far from the end of the world for me.”

That’s a concern. It reminds me of what I would commonly tell people who asked how I felt about putting a roof on Globe Life Field: “Look, even I had to be talked into going to games in August without the roof, and I’m just about the last person who would turn down a Rangers game.” If “it would be far from the end of the world” for Stefan Stahl to have televised baseball taken away, where does that leave the rest of his generation who aren’t as dialed in to the game to begin with?

I think the lockout is hitting me harder than it might have otherwise because, while the game will never lose me, it has already relaxed its grip on the generation after mine. Of the 40 students I have in my SMU class this semester, a class with a heavy sports focus, only three included baseball in a survey of their favorite sports to watch. More damningly, this latest labor strife seems like it could be a setback that costs the sport some of those who have endured to this point.

Actually, it doesn’t just seem so.

“It definitely sucks to have a shortened season two out of the last three years,” Dean says. “I’m very hopeful we don’t miss too much of the season, but every day going forward without baseball, I get more and more worried.”

“Teams can’t put up anything about their players on social media, so all I really see about baseball is old highlights of retired players and media members complaining about the owners,” adds Max. “We’re so distanced from the game now, and I think lots of people are going to get used to that and never really get back into the game when it comes back.”

Garrett isn’t going anywhere himself. The District Underclassman of the Year as a sophomore last season, he has his sights set on playing collegiately (“and maybe even further”) and loves everything about the game: playing it, watching it, reading about it, studying it. But the friction between the two sides whose disagreements have put the game on hold is taking its toll.

“I’m frustrated that we may potentially not get baseball this year,” he says. “I wonder why the game can’t give back to the people who have made it what it is today. The fans deserve everything.”

A union rep or franchise owner or economist might suggest there are some added layers to the idea that the fans make up the most aggrieved faction in the feud. But soon enough, it’s the 17-year-olds who will be the ones deciding where to allocate their ticket-buying dollars. As it stands, it’s going to be an increasingly difficult sell.

I’m a lawyer. I get it. Negotiating can be messy, ugly, contentious. Sometimes the side that comes across as more eager to compromise ends up positioned as the weaker of the two. But I’m not the generation the game needs. Well, for now, maybe I am. But that next generation is one that baseball should recognize it needs—if not at the moment, then no more than a CBA or two from now.

When I was a kid, baseball offered so much that other sports couldn’t. Outside of the action on the field, baseball had postgame fireworks shows, The Bad News Bears, a green Easton. There was no match for Peter Gammons, Vin Scully, or Morganna, the Kissing Bandit. We had no songs about the food you’d get at a football game. Nobody ever brought a scorebook to a basketball game. Baseball at night, no school in the morning.

No other sport had Carlton Fisk moments or Joe Morgan mannerisms you could identify in silhouette. Baseball launched the fantasy sports industry. Baseball cards, in wax packs and in cereal boxes and at the bottom of Slurpee cups, ran laps around other sports. The three buddies I most often traded cards with as a kid—Bobby Mintz, Paul Genender, and Robert Wilonsky—were all friends from the basketball court. We never traded a basketball card, and I doubt any of us owned one.

The game seemed more accessible because you didn’t need to weigh 275 pounds, jump out of the gym, or run like Carl Lewis to excel. Dreaming big was within reach. But fewer kids these days latch onto that dream.

It’s not that baseball isn’t trying. Things have gotten better on the marketing front. But MLB is not nearly as proficient as the NFL or NBA at promoting its star players, something Garrett notes by pointing out that “if you just look at followers on social media, Mike Trout—pretty much the face of the game—has equivalent followers to an average NBA or NFL player.” (He’s mostly right: Trout has 2.5 million Twitter followers, roughly the same as Clippers forward Paul George, a really good player who is hardly the face of his league. LeBron James sits at 51 million.)

The energy of the game can’t compare, either. “I know a lot of people my age claim that baseball is boring, and I don’t blame them,” Stefan says. “If you don’t really understand what’s going on with pitch sequencing and shifts, then all you’re watching is a guy throwing a ball repeatedly, which isn’t that fun.”

But there does appear to be an enlightened effort afoot to close the gap. For Pearce junior Cole Prengler, a pitcher-catcher whose baseball memorabilia collection would rival any from my own generation, the recent uptick in pitcher velocity and home-run metrics helps keep his age group engaged, as has the advent of the Field of Dreams Game. For Stefan, the league’s “Let the Kids Play” campaign has been a welcome turnabout, hyping bat flips and vocal pitchers in place of the unwritten rules that had long condemned them. Apple’s partnership with MLB, announced on Tuesday, to offer an exclusive “Friday Night Baseball” doubleheader on its Apple TV+ streaming service probably strikes the tech-savvier demographic as another step in the right direction.

But for others, the small measures aren’t moving the needle enough, especially for a generation accustomed to instantly viral Ja Morant and Patrick Mahomes highlights and real-time fantasy football scoring updates.

Dean, who hopes to play both baseball and basketball in college, notices the difference firsthand. He has friends who “barely know Juan Soto and Mike Trout are.” Fantasy baseball would be a great way to bring his friends up to speed—if he could get enough of them interested in playing in a league. No chance, he says, with MLB’s blackout policies. “Fans should be able to watch their local teams no matter what. That makes no sense to me.”

Already, it’s taken a toll: Max’s friends who used to consider themselves Rangers fans have fallen out of a routine of watching the team every night between Bally Sports being limited to so few cable and streaming services plus MLB.TV blacking out local teams. Most are gravitating toward the NBA to fill the void.

Maybe they’d have wound up there regardless. After all, Max’s love for the NBA transcends what his favorite players do on the court. The league embraces its athletes’ stories, which in turn makes it easier for fans like him to emotionally invest in the sport he’s watching. He doesn’t see the same level of effort coming from baseball.

“For the most part, I only know MLB players for the players they are,” he says. “For NBA players, though, I know so many of them for the people they are as well. [It] makes the game way more interesting and engaging.”

The league also doesn’t shy away from celebrating and marketing the emotion of the sport the way baseball’s unwritten code of conduct so often has. As a result, Garrett believes baseball isn’t giving younger fans what they really want.

“People who don’t play baseball [seem to think] you’re not allowed to have fun,” says the shortstop, who counts the flamboyant Fernando Tatis Jr. among his favorite players and who isn’t afraid to bust out a quality bat flip. “I understand that you need to respect the game, but to an average fan … it could seem boring.

“People want to see highlight plays. So how is baseball supposed to produce them when it’s frowned upon?”

A 2017 Sports Business Journal survey suggested that the average MLB fan is 57 years old—an astonishing 15 years older than the average NBA fan, with football and hockey fans nestled right in between. It’s hard to imagine baseball has since managed to close the gap measurably, if at all. It’s going to take a major boost in Gen Z engagement to change the math.

Case in point: Caden Varner, a junior outfielder-pitcher at Pearce who hopes to play in college. He calls himself a casual baseball fan, though that wasn’t always the case. When he was younger, he couldn’t get enough of the game, going to Nick’s Sports Cards in Richardson every Sunday with his father—“the highlight of my week”—and eagerly awaiting Opening Day, which he always associated with the beginning of summer.

Now, he says, he rarely watches ballgames during the school year. Other than when he’s on the field, “baseball [has become] a background part of my life,” he says. Now, when he thinks of Opening Day, he can’t shake the image of MLB Commissioner Rob Manfred smiling and laughing at the press conference at which he announced the cancellation of the first week of the 2022 season—the first week of the Corey Seager/Marcus Semien era in Texas.

Caden’s engaged, but not to the level that can sustain a sport. His friends are mostly in the same boat. “It’s always, ‘Oh, did you see the game?’—and that’s it,” he says about the depth of baseball talk they tend to have. “No debate about who we think is going to make the All-Star Game, who the top five shortstops in the league are, or, if we could get anyone’s autograph, who would it be?”

“I would say my friends who don’t play baseball like it but don’t love it,” adds Cole, whose ritual of getting away to Arizona for a spring training trip with his father appears to be a no-go this year. Minor leaguers are there—the major leaguers are locked out of camp—but right now only credentialed media are allowed to be at the workouts (likely a hedge against opposing scouts sneaking in just in case this winter’s Rule 5 Draft still happens).

Spring training: another separator baseball has always had. Football training camps draw some fans but mostly locals; it’s not anywhere near the same stratosphere of Cactus League and Grapefruit League Februarys and Marches, where sunshine beckons, football is in hibernation, and the NBA and NHL aren’t yet in the games that matter most. Only NCAA March Madness truly interferes, and that’s not until spring training is past its midpoint.

Except for this year.

For Caden, the missed opportunity of a spring training that, even in its scaled-down form, is locking out fans is just another example of baseball missing an easy mark. While he recognizes, for instance, that the league has justifiably built a marketing campaign around Shohei Ohtani, he feels that his passion for the sport might have been preserved if there were more players promoted locally.

“As a fan, you want to see players from your team getting recognition,” he says. “When you don’t see that, it makes you think that not only is your team getting [overlooked], but you as a fan are getting neglected, too.”

Preach it, Caden. I still remember those All-Star Games highlighted by a Jim Sundberg pinch-hit appearance or a Jim Kern middle-innings call to the pen.

Does that level of passion for the great game still exist, even among the kids who care about it the most? Maybe they’re not terribly affected by the CBA deadlock or the six weeks that the two sides took off for the holidays. Baseball is counting on that. But are baseball’s flag bearers prepared for the possibility that the younger segment will treat a significantly abridged season not with contempt, but indifference?

And is that what is going to happen? Let’s ask them. Take a look up from your screens for a second, guys. Hit pause and put the console down. Question: will baseball, despite its self-inflicted damage, keep its grip on you? Do you have enough passion for the game that you’ll fully embrace it once it’s back? Is your love of baseball deep enough that you can’t wait to pass it on to your own kids one day?

Stefan: “I think although MLB has done an abysmal job keeping up with the popularity of football and basketball and other sports, I would still want my kids to be interested in the game. I love the game of baseball as a concept, and I want to pass the opportunity to love this game on to the next generation.”

Cole: “I hope younger generations still [care about] the MLB so I can bring my kids to games like my father did for me.”

Dean: “I do hope they come to love baseball. There really is nothing in the world like it, and it has brought so much joy and excitement in my life.”

Max: “I don’t want to take away the opportunity for my kids to love the sport the way I did just because of the state of the league.”

Garrett: “I hope that one day I can instill the same love for the game and give them a chance to fall in love with the sport … and all the great memories and experiences that It can bring you.”

Caden: “Baseball has been a very influential part of my life, and I want to be able to give my kids the same opportunity. Even though my fandom has dwindled down, I think that my kids’ generation will be the ones to see a new, fully revolutionized game.”

Now there’s an energizing thought.

“My best memories growing up had something to do with baseball,” Max says. “There’s nothing like walking into the ballpark on a summer afternoon or being in Surprise for spring training. I go almost every year, and that’s where my oldest and best baseball memories are. Spring training was always so perfect, being right there with the players, watching them up so close, and getting to meet them as they go from field to field.”

Well, that’s a relief, as much of it as I subjected him to—oh, OK, there’s more?

“I just miss the little things of the offseason, and I know that in a few weeks, I’ll really wish Opening Day was on,” he adds. “It’ll hit me when the season was supposed to start that I’m sad the game isn’t there.”

Same.

“I would like to play baseball for as long as I can. I want to play in college and in the big leagues. I love baseball, and it would be really cool to have a part in helping the game be a better version of itself. Staying in the game would help me do that.”

Staying in the game should be at the top of baseball’s aspirations for its youngest fans. Yes, the sport badly needs to attract more teenagers. But hanging onto the ones who have taken the gut punches and are still upright is crucial.

The game will be back. But will the kids?

The ones who love it the most, jilted as they might feel, will probably stick it out. Bitter, maybe, but not enough to walk away.

But the ones who are on the verge of tune-out? A lack of interest would be far worse for baseball than a lack of sympathy. It’s more than a little heartbreaking for someone who loves the game as much as I do. And I’m not even 57.

On their level, it’s not about who’s right or wrong in the CBA stalemate. The fact that the game is presently shut down at the exact time when the excitement level for fans in 30 markets should be at its peak—with kids’ optimism the most genuine and pure—is the problem for that segment of the population for whom the game is still simply a game. Not the Competitive Balance Tax. Not pre-arbitration bonus pools. Not a draft lottery.

The problem for the kids is that there is no baseball.

Meanwhile, the fight drags on over money—money that is directly invested or at least driven in large part by the game’s fans. The ones who will be counted on to invest family money and family time in the game over the next decade or two, the ones who are only old enough now to imagine what it would be like to take their own kids out to the ballgame, are not too far from representing a critical mass for a sport that is fighting to maintain market share.

Max and some of his teammates may be the outliers. For others their age, it might be worth asking whether their generation, with all the options they have, has largely turned its back on baseball—if not just the opposite.

Get the ItList Newsletter

Author