The only person in the world who wanted Dirk Nowitzki on his basketball team as much as Don and Donnie Nelson calls me from his home in Las Vegas. He wants to talk about the one that got away.

His name is Scott Beeten, and his story begins in Augusta, Georgia, back in July 1996. Back then, he was an assistant basketball coach at George Washington University and about to become an assistant at the University of California, Berkeley. Augusta was hosting some 20 AAU teams over four days at the inaugural Peach Basket Classic. The headliners were New Yorkers Elton Brand and Ron Artest, teammates on the Riverside Church Hawks, a group that has been hailed as the greatest AAU team of all time. But Beeten was more interested in an unheralded athlete, a gangly blonde German who was 6-foot-10 going on 7 feet and preferred the perimeter as much as the paint. Nowitzki.

He had only been playing basketball for about two years then and came to Augusta as part of an all-star team of European teenagers. In their first game, they lost to Augusta Metro, a collection of the best players that lived near the Georgia-South Carolina border. Nowitzki managed just six points. With games being played simultaneously and top American talent on every court, most people had their eyes trained elsewhere. But Beeten knew something they didn’t. He was there for Nowitzki, and he spent most of his time in Georgia fixated on him.

“He just had it,” Beeten says. “If you can possibly define what the word ‘it’ is, [Dirk] had it. It just seemed like the entire game or games that we watched him, everything seemed to revolve around him.”

Over the next couple of years, Beeten made red-eye trips to Germany to watch Nowitzki play. He wrote him letters every week and called him on the phone to ask about his practices and his games. He befriended Nowitzki’s parents and his mentor, Holger Geschwindner. Meanwhile, all the Nelsons had seen of Nowitzki was a grainy highlight reel. Like almost everyone else, they didn’t get to know him until the 1998 Nike Hoop Summit, the performance that put Nowitzki on the map.

Prior to that game, Nowitzki seemed destined for a place far away from Dallas. It wasn’t Auburn, either, despite Charles Barkley’s longstanding insistence that he tried to recruit—and bribe—the German teenager to attend his alma mater. Scott Beeten was certain. Dirk Nowitzki was on his way to becoming a Californian.

A few years before that Augusta tournament, Beeten and George Washington University head coach Mike Jarvis were walking near the Washington, D.C. school’s student union. Students were eating lunch and conversing in languages the coaches did not understand. Jarvis had an epiphany: why not make George Washington, situated next to embassies of more than 175 countries in the U.S. capital, the top destination for foreign basketball talent? And why not have Beeten lead the charge?

He just had it. If you can define what the word ‘it’ is, [Dirk] had it.

Scott Beeten

This was the early ‘90s, and while some established overseas players like Dražen Petrović, Toni Kukoč, and Šarūnas Marčiulionis went straight to the NBA, nearly all of the best high school basketball prospects went on to attend American universities. Before winning two titles with the Rockets, Nigerian immigrant Hakeem Olajuwon captivated the nation as part of Phi Slama Jama at the University of Houston. Detlef Schrempf, a German who was drafted by the Mavericks and later formed half of the greatest NBA Jam duo in history with Shawn Kemp, played four years at the University of Washington. Young international talents needed to mature as athletes. They had to prove they were more than an image on a VHS tape. And college coaches who made inroads to foreign talent pipelines could reap a windfall.

Beeten did not have the CV of a savvy international connector. His foreign expertise was limited to an exhibition basketball tour in Israel and a walk across the bridge to the Canada side of Niagara Falls. Seeking out any help he could get, he found Netherlands-based NBA scout Rob Meurs. “I just blindly called him out of the blue,” Beeten recalls. “And I said, ‘Listen, I don’t know anything about recruiting overseas. Can I come over? And can you help me?’” Meurs liked Beeten’s honesty and became a key connector, introducing Beeten and Jarvis to future first-round pick Yinka Dare as well as Alexander Koul, who led George Washington to berths in the NCAA Tournament and NIT.

The summer of 1996, Meurs flew to Augusta with Europe’s best high school-aged players. He gave Beeten a new lead: Nowitzki, a raw but talented wing, was going to be there along with his coach and mentor, Geschwindner. Nowitzki wasn’t a complete secret; Meurs shouted him out in the Augusta Chronicle, describing him as “a very good young player.” But the recruiting game wasn’t yet set up for international talents to generate hype. The internet still came in a disc in the mail, and the local newspapers and recruiting newsletters that followed prep hoops only rated players in North America. Even the Peach Basket Classic ranked behind more notable AAU tournaments that summer. “There weren’t a lot of scouts in the gym. It wasn’t on the big-time circuit yet,” says Van Coleman, a longtime scout and recruiting analyst.

That was fine with Beeten, who liked what he saw. Beeten could not speak with Nowitzki due to NCAA rules, but he introduced himself to Geschwindner and let him know he wanted to recruit Nowitzki. The next year, Beeten took an assistant position at Cal, helping head coach Ben Braun with a roster featuring future NBAers Sean Marks of New Zealand and Francisco Elson of the Netherlands. Nowitzki was their new top international target.

The first time he met Nowitzki, Beeten had a beer in his hand. (This was Germany, after all.) He had arrived in Frankfurt and drove to the Würzburg X-Rays’ gymnasium. After somebody got Beeten a lager, Beeten found a spot along the baseline where he could watch Nowitzki hustle through warm-up drills with the X-Rays.

Nowitzki saw him, too. All of a sudden he darted away from his teammates toward Beeten and gave him a big hug. “And I remember he spilled the beer all over me,” Beeten said.

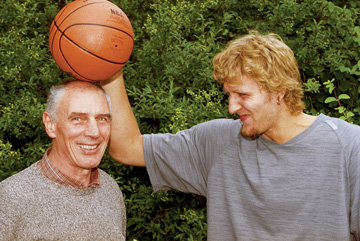

Beeten had been recruiting Division I athletes for about 15 years and would do so for several more. He can’t think of another player who raced off the court to greet him with a hug. But his recruitment of Nowitzki was filled with refreshing experiences. Beeten traveled to Germany about a half-dozen times, usually on overnight flights so he could arrive in time for Sunday basketball. After the games, he would join what seemed like everyone in town at a local pub owned by a friend of Nowitzki’s sister, Silke, and eat dinner with Geschwindner and the Nowitzki family. During one trip, Braun and Beeten stayed up late at the pub with Geschwindner and Nowitzki’s father, Jörg-Werner. “It was such good people,” Beeten says. “When you’re [recruiting] and dealing with good people, it really is fun.”

I think that’s what makes him special—not the talent. I’ve seen a lot of great players in my life and been fortunate enough to be around a lot of great ones, and he’s special. He’s a special person.

Scott Beeten

Beeten kept sending letters and making phone calls. Nowitzki kept getting better, surprising Barkley at a Nike Hoop Heroes exhibition game in Germany in September 1997. Around Christmas that year, Nowitzki and Geschwindner came to the Bay Area for an unofficial visit to Cal. They had some fun—Beeten recalls a side trip to Alcatraz being on the itinerary—but the intense Geschwindner didn’t want any days off for his protege. Beeten and Braun secured space at the Golden State Warriors’ practice facility on the top floor of the downtown Oakland Marriott so Geschwindner could put Nowitzki through his famous workouts that melded basketball and physics. The Warriors’ offices overlooked the court. Beeten told head coach P.J. Carlesimo, assistant Rod Higgins, and vice-president Al Attles they needed to watch.

Yet Nowitzki’s name mostly remained an afterthought to the college basketball powerhouses, who had signed many of the top high school players a month earlier. One of the few mentions of Nowitzki in recruiting stories indicated the other schools that showed interest were Kansas, Villanova, Ohio State, Clemson, Stanford, and Boston College. A Penn State assistant coach visited Nowitzki in Germany, too. But Coleman, the longtime recruiting analyst, remembers Cal being more involved. “Cal was way ahead of the power curve on Dirk,” he says.

Braun says he envisioned playing Nowitzki as a guard-forward, using ball screens to free him up for three-pointers. And for a moment, it seemed like that might actually happen, too. During that December trip, as the Golden Bears played a game in Oakland, Beeten looked up in the corner of the rafters and saw Geschwindner and Nowitzki, his long legs sprawled over the seat in front of him, sitting by themselves.

Somehow, he was still Cal’s secret.

In March 1998, the Nike Hoop Summit pitted the top high school players in America, including consensus No. 1 recruit Al Harrington, against a World team of players from around the globe. Nowitzki almost didn’t play. For one reason, he was in the German Army and had to ask permission to leave the country. Plus, back in Würzburg, the X-Rays were in the playoffs, and Geschwindner knew the team didn’t want its best player, who was averaging 30 points, 16 rebounds, and 9 assists per game, leaving at a crucial juncture of the season. To make it to America, as Nowitzki explained to ESPN’s Tim MacMahon a few years ago, he and Geschwindner basically “snuck out” on a Monday morning after a basketball game.

They did give a heads up to Cal, so Braun traveled to San Antonio to watch the Hoop Summit in person, the anxiety in his stomach growing as Nowitzki erupted for a game-record 33 points and 14 rebounds in front of top Division I coaches, NBA personnel, and a national audience on ESPN. “He had a breakout game there, and I went, ‘Oh, shoot, that’s not good for Cal,’” Braun says. In the span of an afternoon, Nowitzki went from being virtually unmentioned in U.S. media and unranked on recruiting lists to having thirty-six college offers and a new reputation as “the clear-cut top player in this year’s recruiting class.”

Would he go to college, stay in Europe, or enter the NBA Draft? Geschwindner and Nowitzki kept all their options open and whittled their college choices down to two finalists: Kentucky and Cal.

When Nowitzki arrived in Berkeley in early May, Braun and Beeten thought they still had a chance. Nowitzki got to campus just as Braun was finishing a tennis match. “And he said, ‘Let me play you in tennis,’” Braun recalls. The head coach came up with a fun bet: if Braun won, Nowitzki would sign with Cal. He had no idea Nowitzki was once an excellent youth tennis player. Sure enough, after one set, things weren’t looking good for Braun. “I remember Ben hitting a bullet shot and hitting Dirk with the ball while they were playing,” Beeten said. “And I call Ben over and said, ‘Ben, what are you doing?’”

The coaches assigned Sean Marks as Nowitzki’s host. During his short time in Berkley, he scrimmaged in a pickup game organized by the team. J.T. Stephens, a walk-on, remembers watching from the sidelines as Nowitzki buried a three-pointer over Francisco Elson. Elson guarded him tighter to respect his jumper, so Nowitzki drove and dunked on him with two hands. “You were seeing the future of basketball,” Stephens says. “I remember being like, ‘This is where the game is going.’”

Geschwindner and Nowitzki made a side trip to the Grand Canyon before heading to Kentucky, which recruited him intensely after the Hoop Summit. Then they went back to Germany, where Nowitzki declared for the NBA Draft.

You were seeing the future of basketball. I remember being like, ‘This is where the game is going.’

J.T. Stephens

Still, there was hope. As Geschwindner later told SLAM, Nowitzki had the option to withdraw from the draft. His camp was still operating on the assumption that he would ultimately go to college for a year or two.

As much as Braun and Beeten wanted Nowitzki at Cal, they knew the NBA was a tantalizing option. It didn’t help, either, that the Hoop Summit had been in the backyard of the Mavericks, who were now hot in pursuit. Before playing in San Antonio, the international players stopped in Dallas for a week of practices, where they were coached by Donnie Nelson. Nelson was still relatively unfamiliar with Nowitzki, later telling MacMahon he had only seen him on “bad, grainy tape,” but he and Don Nelson watched closely as the World team worked out at the YMCA on Akard Street. When Beeten began recruiting overseas and asked people like Meurs for advice, he also placed a call to Donnie Nelson, who had coached the Lithuanian national team. Beeten had a feeling Nelson would recognize Nowitzki’s gifts.

May and June were rife with speculation as Nowitzki pondered his decision. The San Francisco Examiner reported Nowitzki had decided against the NBA, while the AP said then-Celtics coach Rick Pitino hosted a secret workout for Nowitzki in Europe. Even Barkley crept back in the picture, reportedly calling Nowitzki to tell him to go for the NBA money. The Mavericks downplayed their interest in the press. “Hey, maybe we will take him,” Don Nelson told the Dallas Morning News. “You never know, do you?”

Beeten says Cal knew where Nowitzki stood: “I still remember spending a lot of time with Holger and he said, ‘We really liked those other places, but we just feel more comfortable with you guys.’ … And he basically said to us, if he doesn’t go to the NBA, he’s going to come to Cal.”

About 10 days prior to the draft, Nowitzki and Geschwindner told Cal that Nowitzki had decided on the NBA. Braun thinks Nowitzki called them to break the news, but it may have been Geschwindner. The coaches didn’t blame him for going straight to the NBA. They just wished they could have had him for one year—as much for his personality as his basketball. “I think that’s what makes him special. Not the talent,” Beeten says. “I’ve seen a lot of great players in my life and been fortunate enough to be around a lot of great ones, and he’s special. He’s a special person.”

California was no longer the destination. By the end of that June, Nowitzki was in Dallas, getting introduced by Don Nelson alongside Steve Nash. Not too long after that, Nowitzki was posing for photographs in cowboy hats and living in Uptown (and getting after it at the Loon). He was a Dallasite.

Get the ItList Newsletter

Author