Dallas used to be a college football town. The art deco facade of the 75,000-seat Cotton Bowl stood as a monument to how much Dallasites loved the amateur game. In fact, it was the frenzy to see SMU running back and Highland Park native Doak Walker that motivated Cotton Bowl officials to add a second deck in 1948. Since then, it’s been known as “the house that Doak built.”

Perhaps hoping to capitalize on that enthusiasm for football, Dallas attempted its first foray into the pro game in 1952. Led by the son of a cotton-milling magnate, a group of Dallas businessmen purchased the lowly New York Yanks of the National Football League. The ownership group of the renamed Dallas Texans included oilman J. Curtis Sanford, founder of the Cotton Bowl game; and architect George Dahl, designer of the Cotton Bowl stadium. Combining Dallas, football, and millionaires seemed like a can’t-miss idea.

It was an absolute failure.

The problem was simple: no one in Dallas cared. The Texans went winless at the Cotton Bowl playing in front of paltry crowds. Their sole victory that year came against the Chicago Bears on Thanksgiving Day in Akron, Ohio. Finally, in November, with the team deep in the red, the Texans left Dallas for good, finishing the season as a traveling team based in Hershey, Pennsylvania. The team relocated the following offseason to Baltimore, where they’d find success as the Colts. The Texans were the last NFL team to go bankrupt.

Dallas, then, figured to be an unlikely place to see professional football thrive and the game transform. But that’s exactly what happened.

The 1960s and 1970s inspired what historian Frank Andre Guridy calls the “sports revolution.” Prior to then, sports in the United States bore little resemblance to what we see today. They were regionally focused, commercially limited, and racially segregated. By the 1980s, things began to coalesce into something more familiar to us today. This revolution made football the national pastime and turned sports into big business. And, as Guridy writes in The Sports Revolution: How Texas Changed the Culture of American Athletics, Texas was at the center of it. Hayden Fry’s time at SMU, the building of the Astrodome in Houston, and the Spurs in San Antonio all helped usher in the new era.

Professional football, too, played a major role.

The Northeast and Midwest had long dominated the game. But it was a set of transformations emanating from Dallas that revolutionized the sport. Despite the failure of the Texans in 1952, the city was poised to make an impact. Like many Sunbelt cities after World War II, Dallas was awash with wealth and had a rapidly expanding population. Oilmen in Dallas had the money and the dedication to change the game.

Less than a decade after the Texans left for the greener pastures of Baltimore, Dallas found itself not with one pro football team but two.

Lamar Hunt was the man most responsible for the revival of professional football in the city. The son of oilman H.L. Hunt—the richest man in the world and a certified weirdo—Lamar was obsessed with sports. Growing up, his fascination with competition earned him the nickname “Games” from his siblings. After an unimpressive football career at SMU, the younger Hunt left the family business and set out to succeed where Dallasites had failed before, sustaining a professional football team in the city.

He was unable to buy an existing franchise or convince the NFL to expand to Dallas—old-guard owners no doubt remembered the debacle of the 1952 Texans—so Hunt hatched a more ambitious idea: start a new league. Composed of other millionaires who had been rebuffed by the NFL, Hunt’s American Football League brought professional teams to cities like Dallas, Houston, Denver, and Oakland. In doing so, Hunt nationalized the game by bringing professional football to markets outside the NFL’s traditional strongholds.

As Hunt’s upstart AFL prepared for the 1960 season, NFL officials fretted about losing future markets. They also worried because the young Hunt had more money than any of them. Initially, Chicago Bears owner George Halas tried to dissuade Hunt from going ahead with his rival league. The young entrepreneur refused to abandon the league he created. Halas determined to bring the fight to him and cajoled NFL owners to approve an expansion team in Hunt’s hometown. This was the NFL’s first expansion since taking on the Cleveland Browns and San Francisco 49ers from a short-lived league, the All-America Football Conference, that folded in 1949.

Early on, Hunt’s Texans had the city’s sympathy. In a letter to the Dallas Morning News, one Dallasite, casting “an enthusiastic vote for Lamar Hunt,” observed, “There’s a hint of sabotage in the NFL’s sudden interest in locating a franchise here.” Not every Dallasite was so supportive. One wrote, “I think Texas is college football minded … A pro football team in Dallas would compete with the colleges … [and] operate to the detriment of SMU.” The writer continued, “I believe a pro team in Texas would operate at a great financial loss.” This Dallasite? H.L. Hunt.

To lead the rival Dallas franchise, Halas and NFL owners turned to a man they had rebuffed years earlier, Clint Murchison Jr. Murchison and Lamar had a lot in common. They were both from Dallas and immensely proud of their home. They were both sons of extraordinarily wealthy oilmen. And they both had the money and dedication to turn Dallas into a pro sports town even if they had to lose millions to do it. Hunt’s Texans and Murchison’s Cowboys both began play in the 1960 season. The competition that would develop between the two teams—a competition for fans, for players, and for the hearts of Dallasites—would remake professional football.

Filling the stadium was a crucial part of the rivalry. Each side resorted to gimmicks to draw a crowd to the Cotton Bowl every Sunday. Hunt organized fans clubs, sent young ladies out in bright red sports cars to sell tickets, and on “Barber Day” offered free admission to anyone who showed up on game day wearing a barber’s smock. Murchison’s Cowboys resorted to fewer stunts. Instead, the oilman used his business connections to become the preferred team of the city’s elite through the influential Salesmanship Club.

Hunt’s efforts to get more eyes on his games would, however, leave a lasting impact on the sport. The 1958 NFL championship game between the Giants and Colts proved that football could be a TV sport. Among the 45 million Americans watching live was Lamar Hunt. Seeing the potential of TV to reach national audiences, Hunt’s AFL negotiated a league-wide broadcast deal with ABC to air every game, netting each team $175,000 per year.

At the same time, NFL owners rejected revenue sharing as verging a bit too much on socialism. Consequently, individual TV deals varied significantly from team to team and served to widen the gulf between the rich and the less rich. Seeing the AFL’s success, NFL owners eventually embraced sharing broadcast revenues. By the 1964 season, each team brought in a million dollars.

As Hunt’s AFL grew in popularity during the 1960s, NFL and AFL owners came around to the idea of joining forces instead of competing. Hunt and Cowboy’s general manager Tex Schramm would negotiate the merger. The two also had the idea of a postseason championship game between the two league winners. The First NFL-AFL World Championship Game—later called the Super Bowl, per Hunt’s recommendation—would be played at the end of the 1966 season. When NFL commissioner Pete Rozelle announced the merger that summer, he was flanked by Hunt and Schramm, two Dallasites. There was no question where the idea had come from.

The ideas that emanated from Dallas didn’t just change how the game was consumed. They changed how the game was played. The Texans and the Cowboys competed with each other to draft and sign players. Oftentimes the Cowboys came out on top, signing local stars such as SMU’s Don Meredith and TCU’s Bob Lilly.

The Cowboy brain trust of Schramm, head coach Tom Landry, and personnel director Gil Brandt revolutionized how teams found talent. Before, general managers relied on a loose network of college scouts to evaluate draftees. Brandt turned the process into a science, sending scouts far and wide with standardized forms to more efficiently compare players. The Cowboys’ success in the 1960s and 1970s relied on tapping into previously overlooked sources of talent like Florida A&M, Ouachita Baptist, and Tennessee State. The team even made early forays into analytics, contracting with IBM to computerize the player evaluation process.

Part of finding talent anywhere included a willingness to sign Black athletes when segregation was the norm. For Hunt and Schramm, segregation stood in the way of fielding competitive teams and making money.

When the Texans made running back Abner Haynes their first-ever draft pick in 1960, he was used to firsts. A graduate of Dallas’ Lincoln High, Haynes integrated college football in Texas when he suited up for North Texas State in 1957. Dallasites were not uniformly in favor of the draft pick. After the Texans’ first exhibition game, one reader wrote in the Dallas Times Herald that “a lot of people … were shocked at the number of Negroes on the Dallas roster.” They continued, “It seems the team would be more considerate of fans in this section of the country and hold the number of Negroes to a minimum … The Supreme Court might force our children to sit in school with Negroes but they can’t force us into the stadium to watch a football game played mostly by Negroes.”

Perhaps the writer was right, and White Dallasites stayed home rather than watch African Americans play football. It was poor attendance, after all, that ultimately drove Hunt to relocate the Texans to Kansas City after winning the AFL championship in the 1963 season. But the relatively short existence of the Texans didn’t prevent Haynes from becoming Dallas’ first black star. At the end of the 1960 season, he was selected as both the league’s rookie of the year and its MVP.

His impact extended beyond the field. While Haynes grew up in the segregated world of South Dallas, the celebrity he earned allowed him to access a world previously denied to him. As John Eisenberg explains in his book Ten-Gallon War, the relationships Haynes forged with his White teammates helped change the social world of Dallas. Haynes joined them to visit “all-white establishments in North Dallas, intentionally forcing the places to drop their policies to let him in.” Pro football teams employing Black players, Guridy remarks, “helped desegregate aspects of Dallas social and cultural life.”

Nevertheless, he spent his prime playing before segregated audiences. For the first half of the 20th century, such segregated sporting facilities were commonplace. During the 1960s, however, stadiums like the Cotton Bowl, just three decades old, were already viewed as relics.

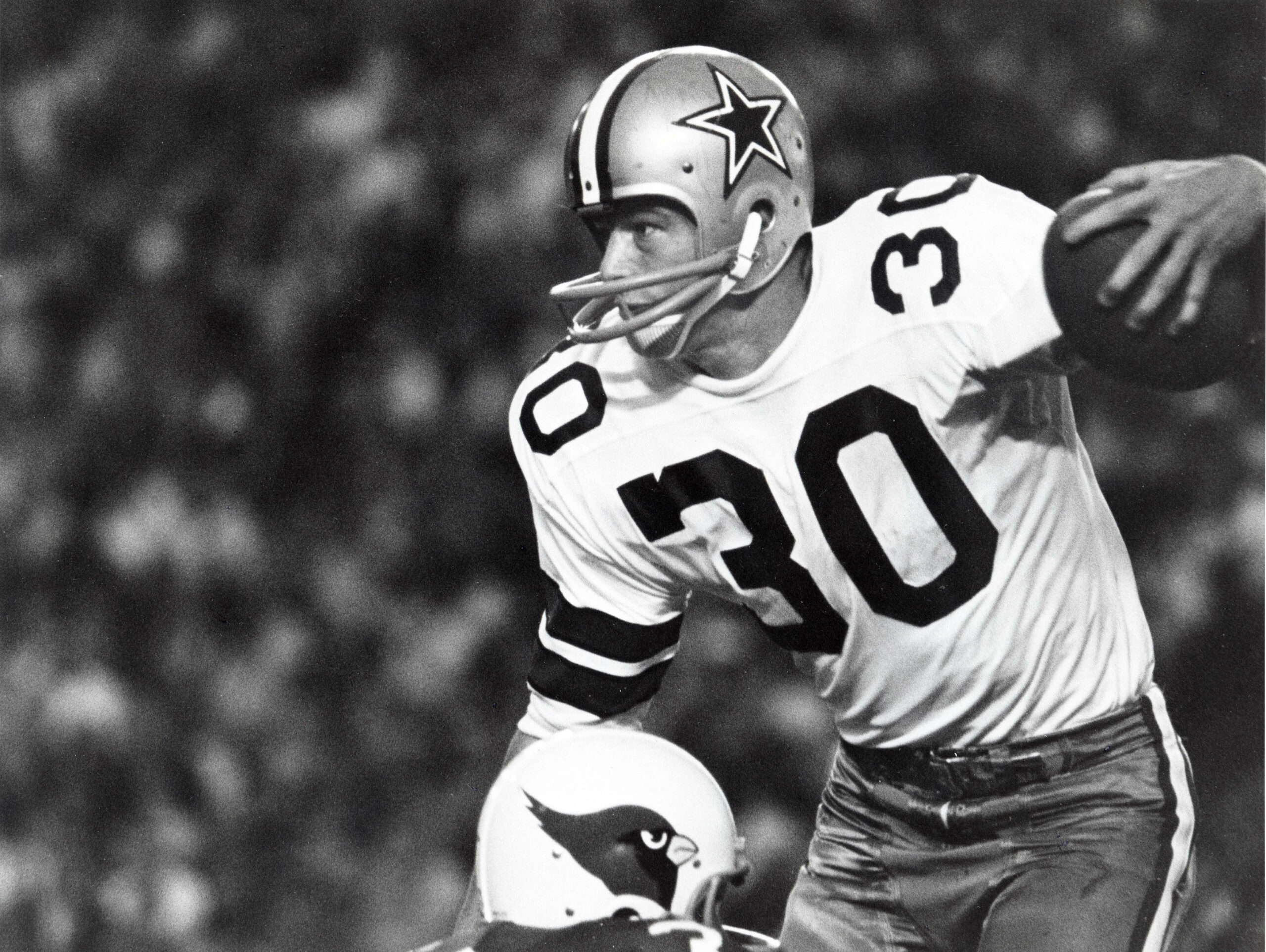

Mandatory Credit: Photo by Tim Heitman/USA TODAY Sports

The construction of Texas Stadium would set the standard for sports venues. Before, stadiums were multipurpose arenas catering to (often exclusively) White, blue-collar workers there to watch the game and nothing else. The Cotton Bowl was a perfect example of the kind of no-frills facility. But for Murchison, there was money to be made in a new stadium by courting racially diverse and more affluent fans.

Texas Stadium demonstrated the growing power of sports entrepreneurs in civic affairs, too. Murchison spearheaded construction in nearby Irving when Dallas Mayor J. Erik Jonsson refused to entertain the idea of building a football-only complex near downtown. In 1967 Jonsson took to the pages of the Dallas Morning News, writing, “The point I want to make … is that I’m a pretty rabid sports fan.” But the mayor went on to dismiss Murchison’s desire for a new stadium as “Astrodome Syndrome,” noting “nobody noticed how bad the Cotton Bowl was until the Astrodome was built.” The new stadium popularized purpose-built facilities with luxury amenities—boasting more than double the number of suites than the Astrodome. “Texas Stadium,” Guridy tells readers, “turned football games into elite private club social affairs.”

But not everyone was happy with the new digs. Mr. Cowboy himself, Bob Lilly, hated it. Compared to the Cotton Bowl, Texas Stadium was, the Hall of Famer recalled during the team’s 1971 Super Bowl season, a “more sterile atmosphere, there just wasn’t a lot of shouting and noise.” This wasn’t the last time a new stadium for the Cowboys would garner criticism for prioritizing refined amenities over raucous fans.

Which was appropriate. Jerry Jones may have taken up the baton, but the foundation for professional football was in place well before him. Men like Lamar Hunt, Clint Murchison, and Tex Schramm were the ones who laid it, from national audiences to revenue sharing, sophisticated personnel evaluation to luxury stadiums. Professional football has become our national pastime because of what happened in Dallas.