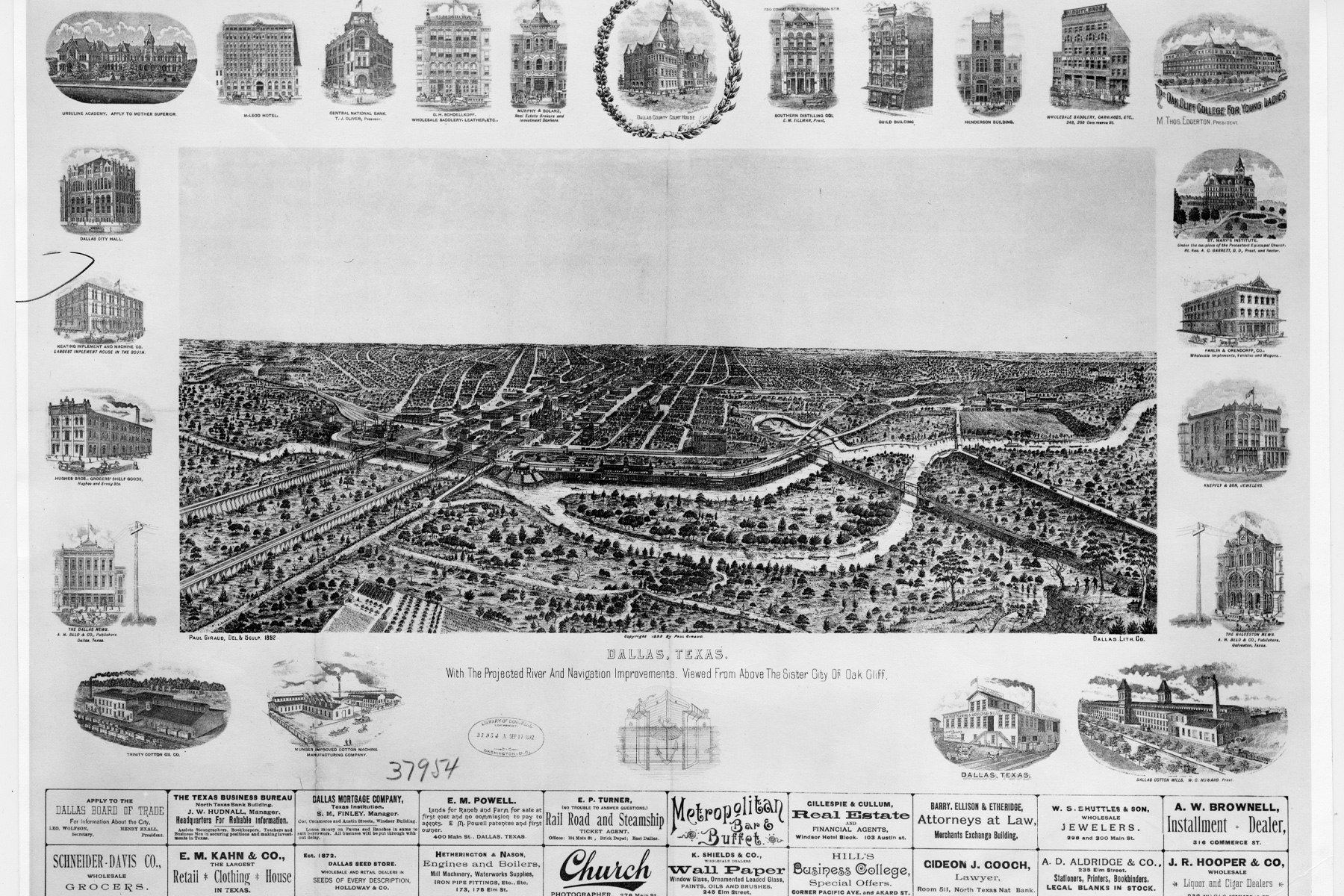

Dallas in 1892 was a city of 38,000 citizens and big dreams. Why not clear the Trinity River of snags and make it navigable to Galveston?

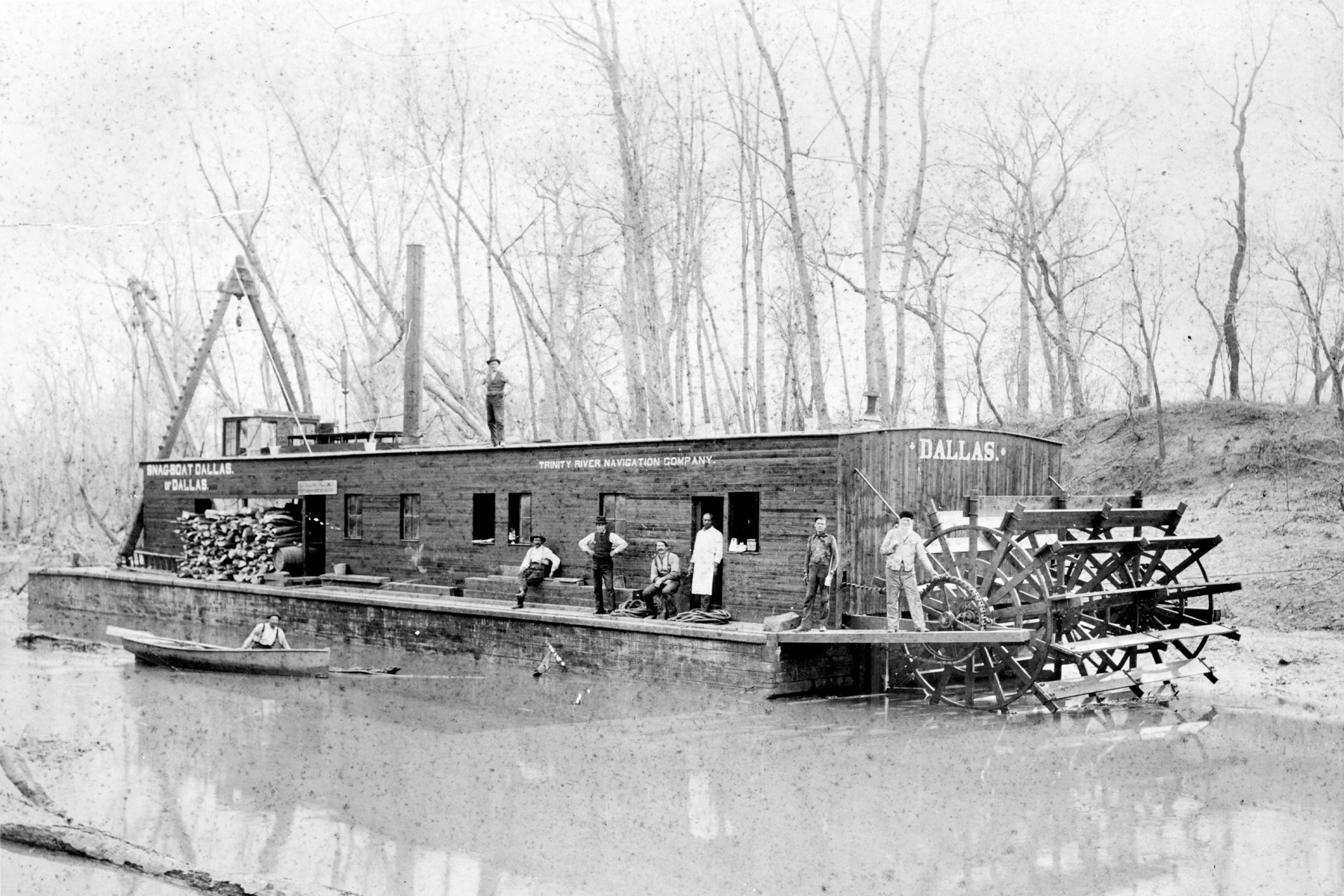

In February, Col. Henry Exall led a meeting of more than 100 people at Dallas City Hall to hear about an expedition that promised to answer that question. James Moroney, son-in-law of George Bannerman Dealey, founder of the Dallas Morning News, had recently captained a flotilla that had navigated the river south from Dallas. His account of the trip was intended to inspire confidence.

The one disappointing note concerned events on the third day of the expedition. “Old man Malcom was not there to welcome us or give us the information we desired in reference to the peculiarities of the great Trinity,” Moroney told those assembled. “For 18 or 20 years he has lived on its banks the life of a hermit, his only visible companion a cat, who at least seemed overjoyed at our coming. The old man we learned had gone to the prairie for the day—possibly to avoid meeting us.”

Moroney ended his report by telling the people at City Hall that the Trinity could be navigated for at least half the year once snags were cleared. His family’s newspaper concluded: “Every man interested in Dallas should be willing to surrender at least a tenth to secure the success of the undertaking … [to] show to the world that the river is navigable.”

Moroney became a stockholder in the Trinity River Navigation Company, which had been formed two years earlier by three ex-Confederate officers and one Union man, Col. William Wylie. Their idea of turning the river into a barge canal caught on with Dallas businessmen who had two things in mind: railroads and timber. The railroads charged too much to move freight. If the Trinity River could be reshaped as a canal, goods could be transported by water for less (which meant leverage for lowering rail rates). A canal would also make available thousands of acres of timberland, and many were keen to bring it to market on barges.

As the years rolled by, there were few gains, yet plans for the project grew larger and more elaborate. The Trinity River Navigation Company pushed for modest improvements to make the river a canal to the sea—a few locks and dams, dredging, and removal of snags and overhanging trees. But the federal government got involved in the early 1900s, with the United States Army Corps of Engineers proposing a plan to dredge the river to 6 feet and build a system of 37 locks and dams along a 510-mile route from Dallas to Galveston Bay.

By the 1960s, the Army Corps proposed a 335-mile route, the reduction in mileage made possible by eliminating the bends in the river. The new plan called for the river channel to be widened up to 150 feet and the dredge depth doubled to 12 feet. Fewer locks and dams were proposed, but the size of the locks greatly increased to accommodate modern barges. And the plan—now with a new name, the Trinity River Project—included the West Fork of the Trinity River and a second port in Fort Worth. Every project includes a certain amount of mission creep, but this was getting absurd.

How did a 19th-century fever dream of moving timber and cotton on the Trinity morph and survive until 1973? There’s a simple answer: a coterie of Dallas citizens pursued federal assistance, and the politicians in Washington made sure the Trinity River received appropriations from the Rivers and Harbors Act. Appropriations were granted at regular intervals between 1852 and 1915. Early funds were used for cleaning hazards from the river; others were used for surveys gauging the viability of remaking the river into a barge canal. The work was carried out by the Army Corps, and its surveys and reports were not always favorable. A report submitted in 1917, and referred to the Committee on Rivers and Harbors in 1921, temporarily halted work.

The Corps had this to say about the Trinity River: “[I]ts physical features are of the most unfavorable character” for commercial navigation. With its narrow, crooked channel and sharp bends, and its reliance on locks that would limit the size of vessels, achieving long-distance navigation was doubtful. If the plan were pursued, it would take a minimum of 15 years to complete at a cost of $13 million (in today’s dollars, about $384 million). But a closer reading of the report reveals something more startling. According to the engineers, it was more likely it would take 78 years with costs rising exponentially after the 15th year. The overall conclusion: “[T]his project is not economically feasible” and “should not be prosecuted at the expense of the Federal Government.”

The report put an end to the construction of any more locks and dams. By 1921, seven locks and dams had already been built, and the Corps recommended leaving them in the river channel with no modifications beyond general maintenance. (The city of Dallas sought reimbursement for nine lock sites that had been secured by “private citizens whose identity may not now be known,” but the request was denied.) Five of the locks and dams are located in the Upper Basin between Dallas and Scurry (near State Highway 34). The first lock and dam, completed in 1909, is located near the McCommas Bluff Landfill.

The scheme to make the Trinity River navigable with federal dollars languished until 1963, but not due to lack of interest from the businessmen of Dallas. After the unfavorable Army Corps report, supporters doubled down, forming yet another group in 1930, the Trinity River Canal Association. The new group included the businessmen of Fort Worth: John W. Carpenter and Amon G. Carter, publisher of the Fort Worth Star-Telegram. Their sons, Ben H. Carpenter and Amon G. Carter Jr., carried the work forward under the group’s new name, the Trinity Improvement Association. (In 1973, it was reported to have 10,000 members.) There were only two things needed to make the industrial dream a reality on the federal dime: a favorable Army Corps report and support from politicians at the highest level of government.

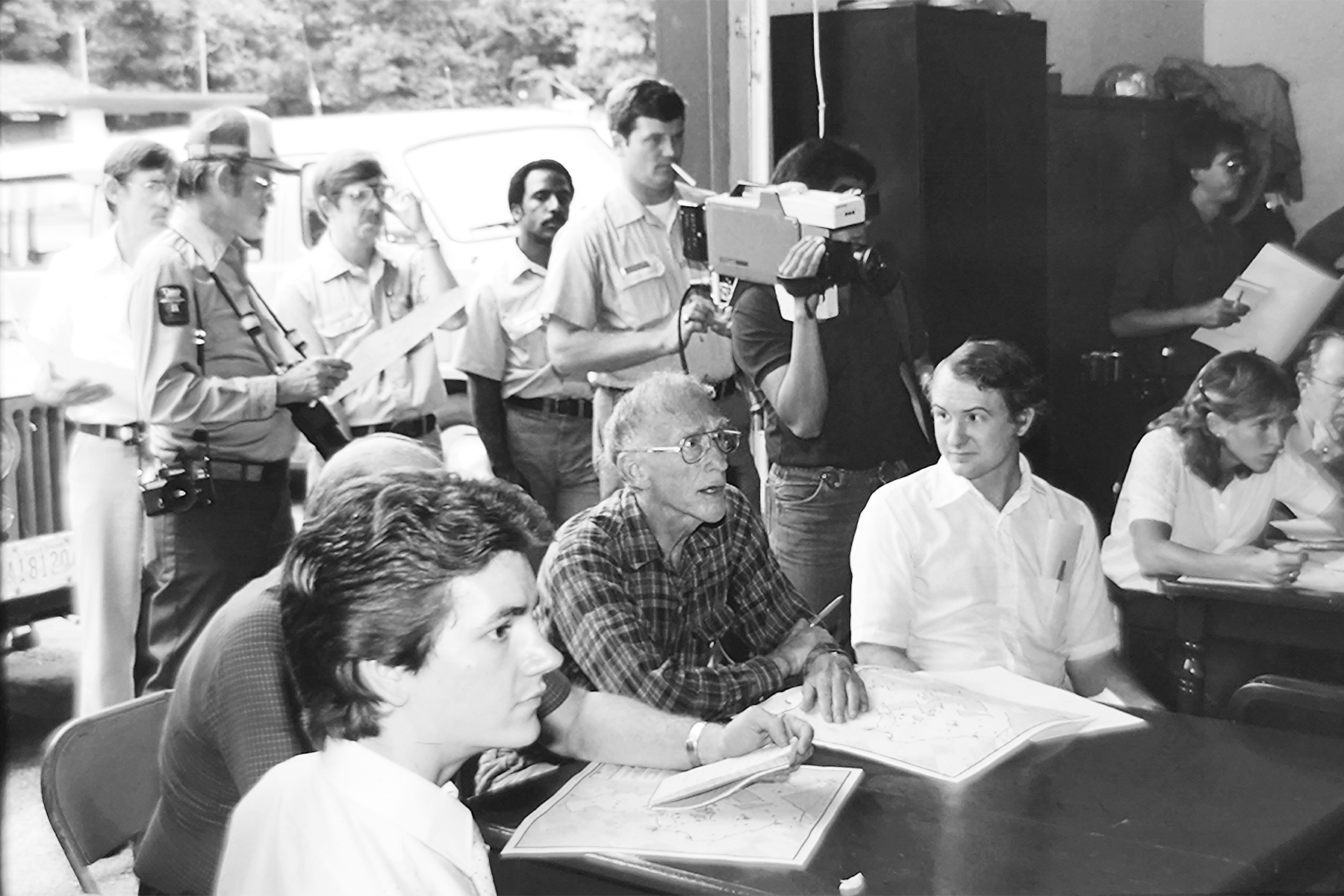

In 1972, a group of people began meeting at Don Smith’s house. Smith, an economics professor at SMU, was joined by a colleague from the theology department, James White; lawyer and ecologist Ned Fritz; Sierra Club member Mary Wright; college student Jim Bush; homemaker Lurline Smith; and businessman Henry Fulcher Jr. They were a diverse group of people with different political leanings but united in their opposition to the Trinity River Project. Some believed the project was a boondoggle, others an ecological catastrophe, and still others thought both. They named their group Citizens for a Sound Trinity (COST).

In the course of the next year, COST formed coalitions and waged a campaign through a variety of grassroots initiatives. Their efforts were met with hostility by canal supporters. Tom Thumb founder and Chamber of Commerce chairman Charles C. Cullum described the group as a “small handful of misguided people” who garnered heavy press coverage “through emotion-packed false claims.” Cullum’s words were included in a letter he sent to employers suggesting they distribute pro-canal letters to their employees.

Ten years earlier, a series of events at the federal level had given supporters confidence their canal was a fait accompli. In 1963, the Army Corps released a favorable report on the Trinity River Project, which advanced to the Committee on Rivers and Harbors. On October 26, 1965, President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Omnibus Rivers and Harbors Act, which authorized construction of the Trinity River Project. The appropriation of federal funds for the project soon hit a snag. The administration’s Bureau of the Budget took issue with how costs had been calculated and wanted a more thorough review. Funding stalled; the project did, too.

Fritz, who was no stranger to taking his disagreements over environmental policy to Washington (and winning), understood the ultimate defeat of the Trinity River Project would happen locally at the ballot box and arguments would need to appeal from a variety of angles. One of COST’s most effective slogans: “Your money, their canal.” To have a voice in congressional chambers, however, would require a Dallas representative who was not Earle Cabell. Alan Steelman, a Republican, ran against Cabell in 1972 and won. Steelman had campaigned on opposition to the canal, calling it a “billion-dollar ditch.” His concerns were also ecological: “The Trinity River is the major geographical feature of the area, and we should not allow it to be destroyed.”

In 1973, it was announced that a stand-alone bond election would be held on March 13. Citizens in 17 counties along the Trinity River would finally have the opportunity to cast their vote on a scheme that had been in the works since 1890. There were two propositions on the ballot proposing a property tax increase to fund a $150 million site preparation for the canal. People were now paying attention; COST filled an informational vacuum at the opportune time. There was something else in the mix: land grabs. An explosive story about the location of the city’s planned port and the Teamsters broke almost a month before the election.

An exposé by News reporter Earl Golz revealed the location of the city’s planned port—at the juncture of White Rock Creek and the Trinity River—and a scheme by four men to buy up land near the site with loans from the Teamsters. One of the men, Morris A. Shenker, was Jimmy Hoffa’s attorney. The men called their enterprise Metropolitan Sand and Gravel. Beginning in 1965, the year President Johnson signed the bill authorizing the Trinity River Project, they started buying land. By 1973, they had amassed more than 3,500 acres along the Trinity River. According to Golz, development on Metropolitan’s land “would be less distance from the gulf than government-owned docks farther north,” and, with lower rates, Metropolitan’s site could be a “formidable contender for all Dallas-based cargo.”

“To save the environment requires great cunning, skill, breadth of appeal, and, therefore, diversity.”

When election day arrived on March 13, voters turned out in unexpected numbers. The down vote won the majority, with Dallas County providing the swing margin. The day after the election, the New York Times predicted that, without local funding, “it now appears unlikely that Congress will appropriate the more than $1.3 billion needed to complete the 384-mile canal, navigation reservoirs, dams and locks required to make the barge system function.” In fact, that is what happened. The COST campaign, Steelman’s outspoken resistance, and the mobilization of voters in 17 counties turned back an almost 100-year-old scheme to industrialize the Trinity River. (The land bought with Teamster loans would later be purchased by the city and used for the McCommas Bluff Landfill and the Trinity Forest Golf Club.)

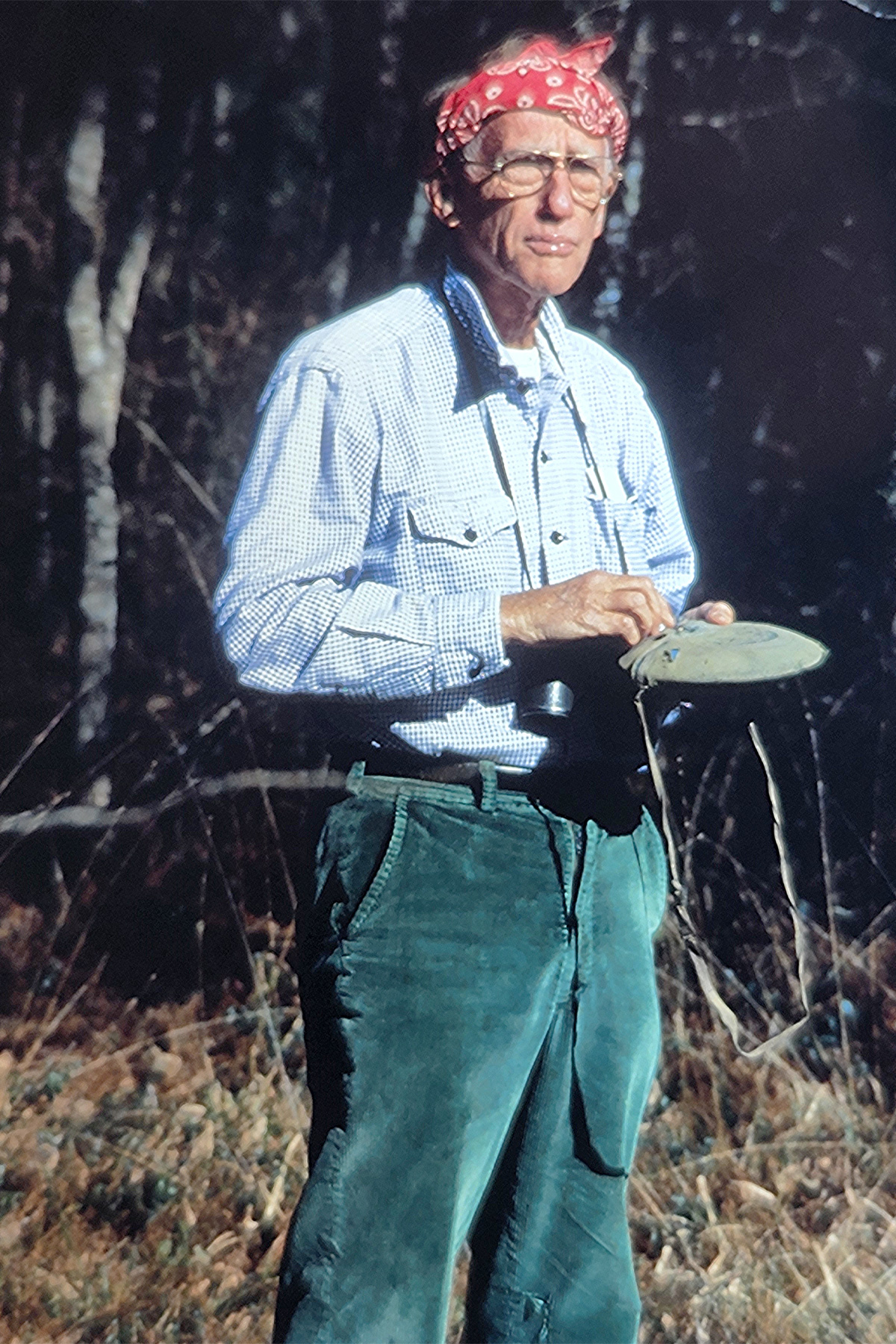

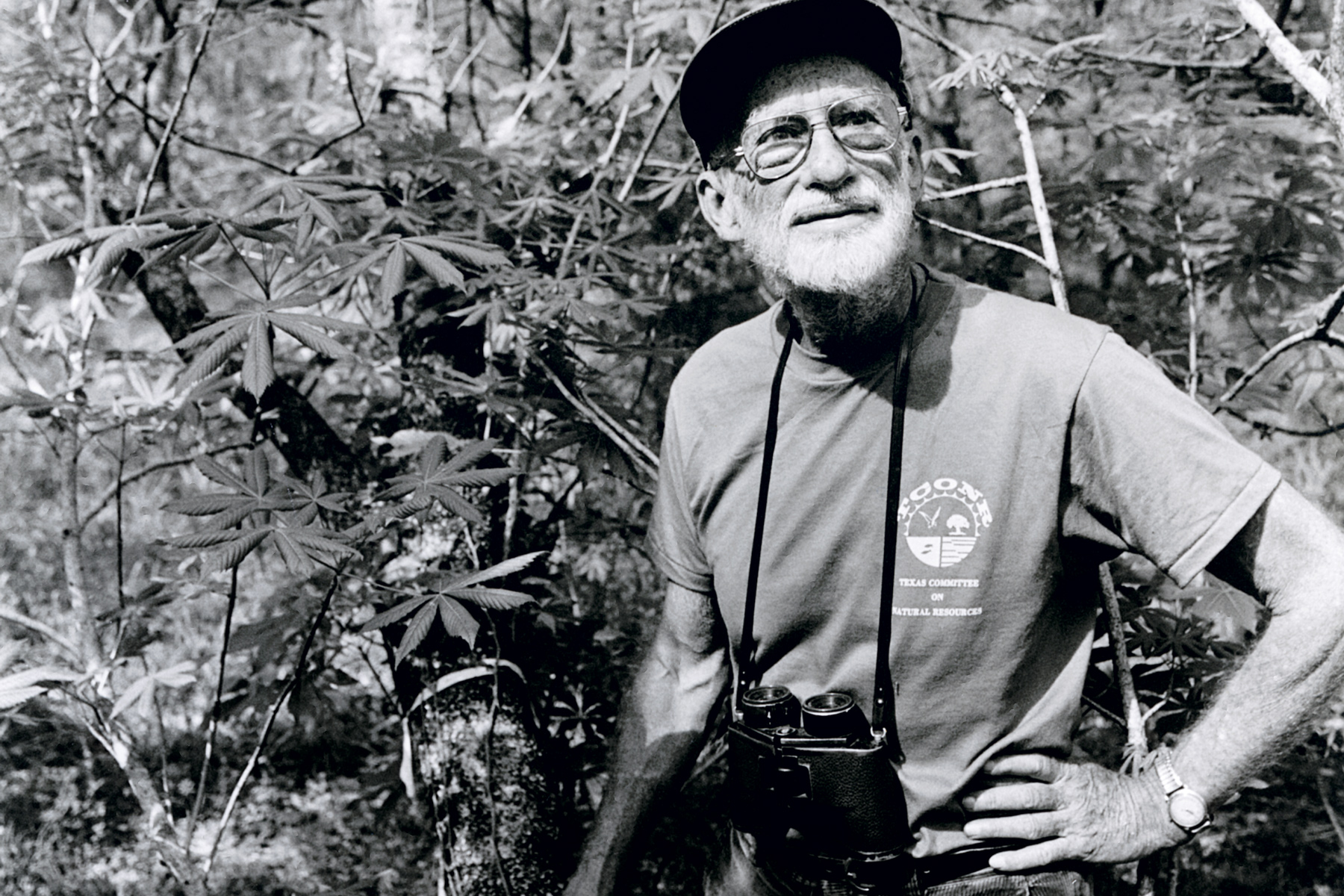

The defeat of the Trinity River Project 50 years ago saved the Great Trinity Forest, site of the proposed inland port, and a river that runs 710 miles from its headwaters to the sea. The hub of the wheel that made those gains possible was Ned Fritz, a man often referred to as the “father of Texas conservation.”

In an interview from 1983, he said everyone has a stake in water projects and all kinds of environmentalists are needed: “The environment is up against entrenched profit-making interest as well as long-standing cultural myths, and so to save the environment requires great cunning, skill, breadth of appeal, and, therefore, diversity. So I’m in favor of everybody joining the environmental movement or participating in it as much or little as they see fit and as they get the enjoyment out of it or as they can afford to do it, you know. From that respect, why, we need the hard-liners. We need real cutting edges.”

Janice Bezanson, senior policy director of the Texas Conservation Alliance, first worked with Fritz on the Texas Wilderness Act of 1984. “Working with Ned was interesting,” she says. “He was very focused and persistent. People either loved him or hated him.” One skill he taught her is “how to take a complex technical document, understand it, and produce a two-page fact sheet that the public can understand.” If Fritz could see it on a map and explain the goal to others, it eventually came to fruition, she says. Bezanson went on to help establish the Trinity River Wildlife Refuge.

Downwinders at Risk interim director Jim Schermbeck never worked with Fritz but did hear him speak once or twice “after the smoke had cleared from the canal fight.” One thing he learned from Fritz is how to approach coalition building. “Ned lined up the local green groups in opposition,” Schermbeck says, noting that Fritz also lined up business interests. “The railroads’ economic self-interests were going to be directly challenged. Why not turn one industry against another and help balance the scales? A lot of people think ‘self-interest’ is somehow a dirty word in politics, but it’s the basis of all coalition building. Unless you address the self-interests of both your allies and opponents, you’ll never win.”

Downwinders is currently working in partnership with Texas A&M and Joppa residents, conducting the Joppa Environmental Health Project to study the health impacts of air pollution. Joppa is a freemen’s town that shares a common property line with the Great Trinity Forest.

Master naturalist and photographer Ben Sandifer met Fritz by happenstance. “Many years ago, I stumbled into a Ned Fritz hike by accident,” he says. “I tagged along and listened to the walk and learned a number of things about the forest.” After Fritz’s death, in 2008, Ben has stayed in touch with his spouse, Genie, a committed conservationist in her own right. “Contemporary Texans should be really grateful of their forward-thinking ideas in protecting the resources for future generations. If channelization had occurred, it would have spelled the end of a great ecosystem that thrived since the Pleistocene.”

Sandifer now leads his own small groups on hikes in the Great Trinity Forest. He says it’s interesting that “some still want to label Ned Fritz as an iconoclast in Dallas. Elsewhere in the state of Texas, he is heralded as a remarkable man who moved mountains and saved some of our most cherished natural spaces.”

Biologist Becky Rader met the Fritzes sometime in the late ’80s. “We have had an unrecognized Trinity Park for decades,” she says. “Ned led us on walks along the river and through the forest, telling us about the history, biodiversity, and importance of its existence in a growing urban environment.” She met Genie through Save Open Space. If the canal scheme had succeeded, she says, the city would resemble the Houston Shipping Canal. “Erosion would be constant, and there would be spread of invasive species from various regions of boat traffic. Think zebra mussels.”

In recent years, Rader has worked in concert with other conservationists to stop destruction in the Great Trinity Forest and along the river. One of their long-term successes has been saving Big Spring, a clear-water aquifer in the forest with historic importance. Part of caring for the spring is regular testing, carried out by Sandifer and Carrie Robinson, members of the Texas Stream Team.

Charles Allen operates a canoe expedition company on the river. He met the Fritzes when opposition was growing to a proposed toll road along the river that was killed in 2017. He views the canal defeat as a victory on many levels. “Ned protected the water supply,” he says. On the Elm Fork, almost 50 percent of the area’s drinking water is floated downstream by gravity from off-channel reservoirs in the north. It’s pulled from the channel into water treatment plants and cleaned before going out in pipes that connect to homes and businesses.

For Allen, it’s difficult to imagine how the city would have managed both clean drinking water and a barge canal since both rely on the river channel. One improvement he would like to see that wouldn’t interfere with municipal operations is the removal of the dams built by the Corps in the 1900s, relics of a failed canal project that impede safe passage in a canoe. “If they were removed, it would mean the ability to paddle into areas nobody goes; the ability to paddle down into the wilderness areas on multi-day trips. Everything downstream opens up, the river curves and bends, and the birds and other wildlife are abundant and thriving.”

This story originally appeared in the March issue of D Magazine with the headline, “Water World.” Write to [email protected].