The fall of 1973 was an exciting time for me. I was a freshman at Austin College, living away from home for the first time in my life and loving every minute of it. That first semester, I somehow managed to maintain a B average despite my short-lived tenure as a pre-med major, surviving an accident where a pickup rolled with eight of us in the truck bed, and discovering a newfound appreciation for staying up late playing guitars and arguing philosophy while consuming mass quantities of beer.

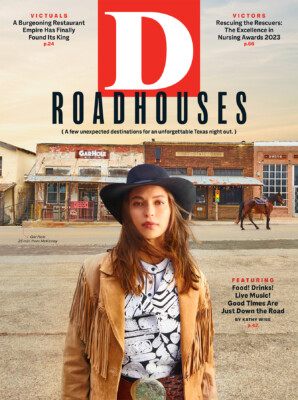

That same fall, Jerry Jeff Walker—an artist of some note who had written the classic “Mr. Bojangles”—had the crazy idea to spend a week recording an album in a century-old dance hall in the Texas Hill Country that was owned by his friend Hondo Crouch. Just about every cosmic cowboy from Bastrop to Blanco showed up. When finished, Jerry Jeff and The Lost Gonzo Band, his crew of musicians that he recruited away from Michael Martin Murphey, headed out to promote their new album.

That tour led them to the small town of Sherman, near the Red River, and the even smaller college I was attending. To say the event was life-changing is an understatement. Shortly thereafter, a good number of students traded their bell-bottoms for Wranglers, bought cowboy hats and boots, put their rock and disco albums on the shelf, and placed Jerry Jeff’s new album on the turntables.

That album, Viva Terlingua, played constantly in our room, which would later become known as the Gar Hole. I quickly learned how to play every song and memorized all the lyrics. I even used the album for a poetry project in an English class, critiquing each of the nine songs. I pored over the liner notes to the point I could tell you even the most insignificant details, which led me to find out about the aforementioned recording site, Luckenbach.

It was around 8 pm on a Friday night that I found myself and a few friends sharing a pitcher at our favorite beer joint, Adair’s, in Dallas. When Jerry Jeff’s song “Sangria Wine” suddenly came on the jukebox, we began talking about this new musical phenomenon called progressive country and, more specifically, Viva Terlingua.

“Did you know they recorded it at Luckenbach?” I asked.

“Luckenbach? Where’s that?” was the reply.

“Just west of Austin,” I said confidently.

We bought two cases of beer from R.L. Adair and hopped in my Jeep. Ten minutes later, we were on I-35, heading south. Three hours later, we were on the outskirts of Austin. (By the way, beer carryout, drinking at 18, and driving while drinking were all legal at the time.)

“Where do we go now?” someone asked.

“West,” I said, and we turned right on State Highway 71. It was well after midnight when we reached U.S. Route 281. It was at this point I finally unfolded the map of Texas that I kept in the glove box and began to search. There was no sign of anything close to being called Luckenbach. Undeterred, I turned left, figuring we’d find it sooner or later. The Hill Country was much different then: no wineries, boutiques, or million-dollar homes. It was mostly mesquite trees and goats. We had driven over an hour before we finally found a remote convenience store that was still open. I went in and asked for directions.

“Luckenbach?” the cashier laughed. “You’ll never find it at night.”

That was all the challenge I needed. I jotted down the few directions he gave me, some as accurate as the number of the county road, others less specific, such as “turn right by the leaning barn” or “left at the Lutheran church.” My buddies weren’t so much concerned that we were lost as they were worried that we were almost out of beer.

Miraculously, at about 4 am, we found the old post office that doubled as a general store and the dance hall where Viva Terlingua had been recorded. They were dark and deserted. With no one around and no more beer, we each climbed onto a picnic table and went to sleep.

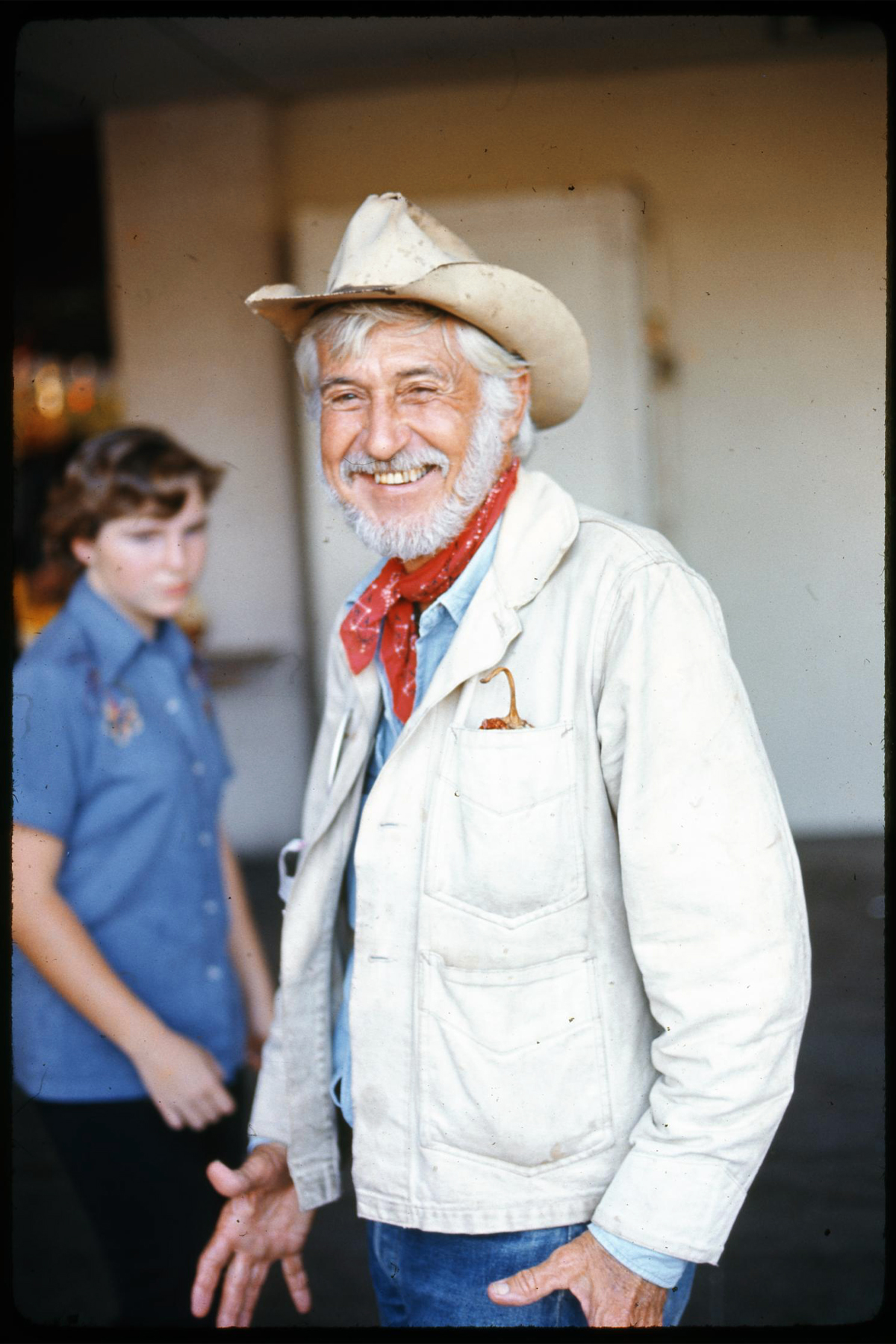

The next morning, we were awakened by a lady who, after asking, “What the hell are y’all doin’?” offered to cook us breakfast. As we washed down some bacon and eggs with a beer, some of the locals showed up, the after-effects of a late night of drinking apparent. They, too, bought beers and quietly took a seat. Around noon, an older fellow wearing a denim shirt and worn-out cowboy hat walked in, and everyone brightened up. I knew immediately who he was from the pictures on the Viva Terlingua album.

Hondo Crouch! Born in the town he was nicknamed after, he grew up with a love of the outdoors. He attended the University of Texas, where he was an All-American swimmer. That’s also where he met his wife, Shatzie, the daughter of a wealthy Angora goat rancher named Adolf Stieler. Stieler’s Angoras produced the majority of the world’s mohair, so Shatzie was Hill Country royalty, educated at a private school in San Antonio and privy to arts and culture. Hondo, on the other hand, was homespun, better suited for whittlin’ and strummin’ his guitar around the campfire, singin’ the Mexican songs he had learned from ranch hands.

They worked together for years at various youth camps, but, with a growing family, it was decided that Hondo needed a more suitable, better-paying profession, so he went to work for Adolf. After Hondo spent many unsuccessful years attempting to fit in at Stieler’s business, Shatzie finally gave up and left Hondo to his own devices, which included buying the ghost town of Luckenbach with his friend Guich Koock.

Hondo was a trapper, a hunter, a craftsman, an entertainer, and, most of all, a storyteller. After meeting him that day, we were treated to an afternoon of conversation with him and his friends, with Hondo dominating, telling one tale after another.

I never had a personal conversation with Hondo, though I met him many times on my trips to Luckenbach. There were always others around. I never saw Willie or Jerry Jeff there, but I often heard stories about them showing up for a beer and a game of dominoes. Despite Viva Terlingua’s success, there really weren’t that many people showing up at Luckenbach, just enough to circle around a tree and play guitars, occupy a table inside and play dominoes, or simply have a beer with friends. That was true of Luckenbach until “the song” was written.

When Jerry Jeff’s friend Guy Clark returned to Nashville after visiting Luckenbach, he raved about it to a couple of his songwriting friends, Chips Moman and Bobby Emmons. Without even visiting Luckenbach, they wrote “the song”: “Luckenbach, Texas (Back to the Basics of Love).” When they pitched it to Waylon Jennings, he told them there was no way he was recording something so hokey. Eventually they talked him into it. Willie Nelson guested on the track, released as the first single off 1977’s Ol’ Waylon, and it topped the charts for six weeks.

Things in Hondo’s little town would never be the same. Suddenly, Luckenbach was a tourist attraction. Willie held his famous Fourth of July picnics there. Soon after, thousands of people began moving to Austin for the job opportunities and lifestyle, and the distance between the state capital and Hondo’s tiny town dissipated.

Hondo’s reason for buying Luckenbach was to have a place where he and a few friends could gather and swap tales while nursing beers; a place where he could write his stories, which he penned under the name Peter Cedarstacker for a local paper; and, most of all, a place where he could create a world that was part historical, part mythical, and absolutely fantastical.

Hondo passed away just before he reached 60 years of age. He owned and operated Luckenbach less than a decade. For a guy that had been such a great athlete and had stayed physically active his entire life, it just didn’t make sense for him to die so young. He had embraced the throngs of people that came to Luckenbach, creating events that packed the place where he served as ringmaster. But maybe that’s what got him. Maybe his connection to nature, his aptitude for entertaining people, and his love of adventure became lost in the shuffle. Maybe the place just got too big, too fast, the expectations too unrealistic, and the responsibilities too enormous for a guy more suited to kickin’ back with friends, guitar in hand, telling a few tales. Maybe it all just broke his heart.

Known as the Clown Prince of Luckenbach, John “Hondo” Crouch died September 27, 1976.

This story originally appeared in the March issue of D Magazine with the headline, “The Town that Inspired Me” Write to [email protected].