Ira Molayo stared into the abyss. As winter turned to spring last year, the pro at southern Dallas’ Cedar Crest Golf Club regarded a figurative end of existence because the grass on the Cedar Crest greens wasn’t. Instead of the usual pool table felt, golfers at the municipal course found a multicolored crazy quilt of corduroy and burlap that Jordan Spieth himself could not decipher. Putting is the game within the game; golfers don’t mind a bit of slope between the ball and the hole, but in the name of fairness, they insist on smoothness. So when even a 3-foot putt would not roll predictably, customers raised hell. They asked for their money back, or they wrote angry emails. Then they stopped coming.

“We started offering discounts left and right, but even after we reduced our fee to $13, play continued to go downhill,” says Molayo (pronounced mo-lye-oh). “All the tournaments we’d booked canceled—except one, one of the Byron Nelson pro-ams. They played on greens that were predominately sand.”

Meetings were held, experts consulted, and Hail Mary cures tried. To no avail: the course shut down for 15 weeks while its greens were plowed up and replanted. Dallas’ six municipal golf courses gross about $4.2 million a year. The closure meant that the city got only a fraction of its roughly $600,000 annual contribution from Cedar Crest; it cost about $320,000 to resurface those bumpy, unlovely greens, and the suddenly unemployed Cedar Crest golf staff had to be supported. That cost the city another $500,000.

Among the scores of people whose lives were inconvenienced—or worse—by the agronomic anomaly, Molayo took it hardest. He is one of the few Black golf pros around. The fate of Cedar Crest is quite personal for him, because he made the place his headquarters when he was a kid. “Every summer morning, Mom would drop me off at Cedar Crest on her way to work and pick me up on her way home,” he says. They lived just 3 miles away. Some days, young Ira would play 54 holes—that’s three rounds, about an 18-mile walk—with a bag of clubs on his back. He loved it.

He also loved music. After graduating from David W. Carter High School in 1995, Molayo had his choice of scholarships based on his talent on the trumpet. Miles Davis and Oak Cliff’s own Roy Hargrove, who won two Grammys, were his heroes on the horn. After an abbreviated stint at Southern A&M University, Molayo chose golf over jazz and labored in the assistant pro vineyard until 2007, when he bid on and won the contract to run Cedar Crest.

His desire to do something for the community and an interpersonal style that gets people on board led to the I Am a Golfer Foundation. The foundation’s co-founder and chairman is another charming and persuasive man, Dave Ridley, who worked for Southwest Airlines for 27 years.

From the IAAGF website: “[T]he mission is to be a catalyst for renewal and transformation in South Dallas through the preservation and promotion of the historic Cedar Crest Golf Course … [to help] diverse and historically underserved communities.” Since its inception in 2018, IAAGF has hosted 71 paid internships and given out about $95,000 in college scholarships. With significant help from Trinity Forest Golf Club, it has also revived the long dormant Dallas Amateur Championship. That is good work.

Closing Cedar Crest at the height of the golf season did not help Molayo’s finances or the foundation’s momentum, of course. The problem was po. Or, more correctly, an infestation of Poa annua, a strain of annual bluegrass that’s harder to get rid of than a bad reputation. Po thrives in cool, wet conditions such as prevail in a North Texas winter, and it’s so hardy that it often sticks around as the weather warms. It tends to grow in patches, like psoriasis. Lots of northern courses have learned to maintain Po as the year-round grass on their greens, but in our latitude it’s an invasive species, like zebra mussels or kudzu, and it can dig in anywhere. Lakewood Country Club superintendent Mike Plummer sometimes literally goes at it with a knife. In 1972, Po even dared to invade the Holy of Holies, Augusta National, home of the Masters. The scores in that year’s tournament were atrocious.

As the weather warmed last spring, and the dormant Bermuda grass on the Cedar Crest greens grew—or tried to—Po was a tough foe in the battle for sun and oxygen. The death knell tolled in April. By then, the putting surfaces had devolved into a slurry of dirt, water, seed, sand, rye grass, herbicide, fertilizer, and too few blades of the desired Bermuda. The plant growing best was algae. Algae! An agronomist from the United States Golf Association happened to come to town during the crisis, just making sure Cedar Crest was ready to host a USGA qualifying tournament in May, but, obviously, it wasn’t. The agronomist told his bosses to find another venue while advising the Dallas Park and Recreation authorities that they should just start over.

Greens are supposed to last 20 years or more, but Cedar Crest also had to close down in 2015. There was a different culprit—according to the official story, salts from effluent irrigation water degraded the greens then—but the same effect, a 15 week shutdown during golf prime time. In 2019, another city-owned golf course, Stevens Park, closed for greens repair from mid-May to mid-July. Upon reopening, Stevens pro Jim Henderson told D Magazine—rather vaguely—that the problem had been “greenskeeper techniques and a preemergent herbicide.” He estimated that lost revenue over that period was $625,000.”

Poa annua and disagreeable gray water are almost acts of God, and no grass likes being shaved to an eighth of an inch, and no greens benefit from the pitter-patter of 35,000 pairs of spiked feet, the approximate number of rounds played at Cedar Crest in a good year. Yet the closures are a powerful argument against the status quo. Observers and insiders are asking why the city doesn’t do what it does with Fair Park, the convention center, the Arboretum, the Omni Hotel, and the Dallas Zoo. In other words, a public-private partnership. In other words, why not hire a management company to run Tenison, Luna Vista, Keeton Park, Stevens, and Cedar Crest? The confusing answer is that it already does, in a way. Molayo and the pros at the other municipal courses are independent contractors who take care of the golf side of things. But maintenance of the ground and the grass is not farmed out. City employees take care of it—usually.

In San Antonio, a nonprofit called the Alamo City Golf Trail operates its eight golf courses—not the city. Of Houston’s five munis, the Houston Parks and Recreation Department manages and operates two, and three are run by private companies. Golf management firms are not a panacea, but sometimes they work very well.

Fortunately, this story of dirty water, bad grass, and questionable oversight has a flip side that’s nothing but sunshine and optimism. Two men illustrate the possibilities. One is Molayo. The other eminence is Albert Warren Tillinghast, the Playboy Architect and the designer of Cedar Crest. Tilly has had twin peaks of popularity: the 1920s and now, 80 years after his death. It’s hard to overstate how important this old dead guy has become in the golf world.

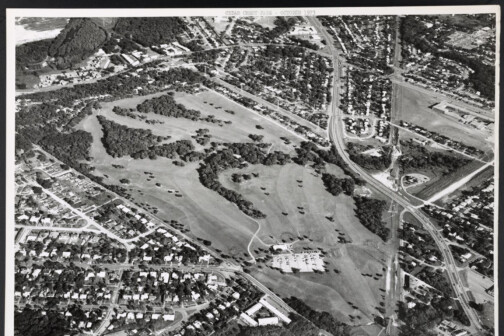

Cedar Crest began life in 1919 as Cedar Crest Country Club, a private playground for well-off White residents of Oak Cliff who could afford the arguably best golf course designer in the world, an interesting chap from New York who was already in town to lay out the holes at Brook Hollow Golf Club. With his bespoke suits, limousine, handlebar mustache, and boozy eyes, Tillinghast looked the part of a wealthy sybarite, exactly what he was. He often backed Prohibition-era Broadway plays—for the after-parties, we think. But he was no lightweight. Tilly wrote prodigiously and pretty well for golf magazines about the emerging art and science of golf course architecture, and he had a keen interest in fine art. Most important, his genius at sculpting ground for golf put him on the Mount Rushmore of golf architects, with his contemporaries Donald Ross and Alister MacKenzie. For non-golfers who don’t get the mania for these three, the most apt comparison might be to Frank Lloyd Wright.

“Tillinghast was much more flexible in his approach than the other two,” says Portland, Oregon-based author and golf architect John Strawn. “Cerebral, subtle, and with a great aesthetic sense. He forces the player to think. The combination of beauty and difficulty is why they have U.S. Opens on his courses in New York [Winged Foot and Bethpage Black] and New Jersey [Baltusrol].”

Sock it to ’Em: Cedar Crest started as a country club in 1919, and Walter Hagen (above) won the PGA Championship there in 1927.

Cedar Crest began life in 1919 as Cedar Crest Country Club, a private playground for well-off White residents of Oak Cliff who could afford the arguably best golf course designer in the world

Cedar Crest staged a minor USGA championship in 1954, a semiofficial recognition of the high quality of its golf course.

The club’s most glorious moment occurred in 1927, when it hosted the PGA Championship, one of golf’s four majors. Walter Hagen won; 15-year-old Byron Nelson watched.

While Cedar Crest is too short and too landlocked to host a U.S. Open, Tillinghast fitted Cedar Crest into the ground wonderfully, and he created par 3s that remain among the best in Dallas. Because he was himself a good player, Tillinghast kept it fun and kept in mind that it was a game, after all: chess on a giant board, with wind and weather and bets and hangovers to contend with. The second hole at Cedar Crest is classic Tilly: a tee shot that asks for a left-to-right spin, into a fairway that bounces the ball right-to-left.

The club’s most glorious moment occurred in 1927, when it hosted the PGA Championship, one of golf’s four majors. Walter Hagen won; 15-year-old Byron Nelson watched. The Depression forced the club out of business. The city acquired it in 1946. Cedar Crest staged a minor USGA championship in 1954, a semiofficial recognition of the high quality of its golf course. Also in ’54, pioneering Black golfer Charlie Sifford won the United Golf Association’s National Negro Open at Cedar Crest. I Am a Golfer, the foundation organized by Ridley and Molayo, plans to erect statues of Hagen and Sifford on a plaza overlooking the 18th green. This statuary is not necessarily a mistake, but it may be a missed opportunity, for while Sifford and Hagen are important symbolically, neither has any agency. Hagen was great, but his prime time was a century ago, and no one ever sought out a golf course because Sifford won there. Tillinghast, on the other hand, puts butts in the seats. He should get the bronze. Visitors would pose next to it.

The Cedar Crest Molayo played on as a kid had changed a lot since its founding as a private club. Conditions on both sides of its fence had gone downhill. The houses huddled on the perimeter were low-slung brick dwellings built in the ’60s and ’70s, many of them retrofitted with bars on their windows and doors. Twenty or so years ago, during one of my scores of rounds at my favorite Dallas muni, a young man approached on the eighth fairway. He held a leash attached to a pit bull in one hand and a paper bag of something in the other. “You want to buy some golf balls,” the salesman said, and it was not a question. Another negative developed slowly: the golf course was adulterated by countless, pointless trees that distort the architecture while depriving the grass of soil nutrients and sunlight. “Cedar Crest is one of 397 Dallas parks,” says an insider who didn’t wish to be named. “And what do parks departments do? They plant trees.”

To conform with the changing demographics, a Black pro, James “JW” White, took the top job at Cedar Crest in 1968. The impressive Leonard Jones succeeded him. Jones would be Molayo’s inspiration, his mentor, and his employer. “His clothes were so sharp. I remember this purple outfit,” Molayo says. “And I remember White guys patting him on the shoulder, giving him a handful of money after a lesson or whatever.”

In October, a couple of weeks after the reopening of the course—the new greens are faster, truer, and generally better than the old ones, by the way—Cedar Crest boosters announced another reason to celebrate. The Southwest Airlines Showcase at Cedar Crest will be a tournament for the top 21 male and top 21 female Black college golfers in the country. Its inaugural event will be held in November. And it will be televised live, nationwide, on the Golf Channel. If all goes well, it will be an annual event.

A happy group of about 50 gathered under the pavilion by Cedar Crest’s 18th green to hear all about it. A dozen dignitaries sat in a row of folding chairs on the redbrick patio just outside the shelter, blinking in the bright sun and waiting their turn to speak.

“We all know that golf was exclusionary, solely based on arbitrary factors,” said Mayor Eric Johnson, who also noted that the Southwest Airlines Showcase at Cedar Crest will be the first-ever live TV broadcast from Oak Cliff.

District 4 Councilwoman Carolyn King Arnold followed His Honor. “We’re so happy that a major corporation is not afraid to come across the Trinity,” she said.

Former Mayor Mike Rawlings observed that “antiquity equals authenticity,” referring to the 100-plus years Cedar Crest has been in business.

Then Ridley gripped the mic, warning upfront that he might orate longer than the others, such is his enthusiasm for the foundation he co-founded, for the community, for Molayo’s work, and for the course. Although it’s virtually “a Rembrandt, a Monet,” Ridley said, “Cedar Crest has been underappreciated and under-resourced. But every city should have a great course anyone can play. Houston does [Memorial Park]. San Francisco does [Harding Park]. And so does New York [Bethpage Black—which is owned and operated by the state of New York, by the way, not by New York City].”

Ridley dares to dream that the old southern Dallas playground could be run by a private nonprofit and returned to its pristine 1920s form. A variety of things make this dream complicated, however. Among them: a total course renovation would cost millions of dollars, money that would probably have to flow from private sources. World-class courses cost more to play and maintain than run-of-the-mill ones; an increased green fee could nudge out the core group of golfers who have made Cedar Crest their home for many years. Reclaiming Tilly would probably begin with a duel between chain sawyers and tree-huggers. And Cedar Crest II might gentrify the neighborhood—maybe a good thing, maybe not.

Dallas Park and Recreation Department president Arun Agarwal says the city knows what it has in Cedar Crest, which was why the Park Department took the hit (twice) of closing the course when weed and water troubles arose; it deserved better than a patchwork job. Without actually saying so, Agarwal hints that the current model of 10-year contracts with pros could be abandoned or changed. Every pro at every Dallas municipal course is right now operating on an extension to his or her contract that will be evaluated this summer. It’s within the realm of possibilities that the city will give up its maintenance of the land and turn over each of the courses to a management company that would oversee everything from the greens to the clubhouse.

“Golf has changed, Dallas has changed, and a new generation is embracing golf,” Agarwal says. “We must find a new way.”

Given the exalted status of its designer, a completely restored and perfectly maintained Cedar Crest could become a bucket-list stop for golf gadabouts from all over the world. Southern Dallas could become a destination. Imagine that.

This story originally appeared in the February issue with the title “Shades of Green.” Curt Sampson is one half of Strawn & Sampson, a book publishing company. Write to [email protected].

Get the ItList Newsletter

Author